Last year, I wrote a short history of the Cincinnati House of Refuge for a website that is currently under development by some UC Librarians which will make the data from ARB’s digitized Cincinnati House of Refuge records more easily searchable. While conducting research on the history of the House of Refuge, I became intrigued with how Cincinnati dealt with children whose parents for one reason or another were unable to care for them in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Cincinnati House of Refuge was designed as a facility for juvenile delinquents, but over time it also came to house children who had nowhere else to go. This fall I am beginning a research quest to piece together why this happened, and when and what alternatives to the House of Refuge were established. I will be writing a series of blog posts on what I find. This first one, though, will provide some background on Cincinnati’s House of Refuge.

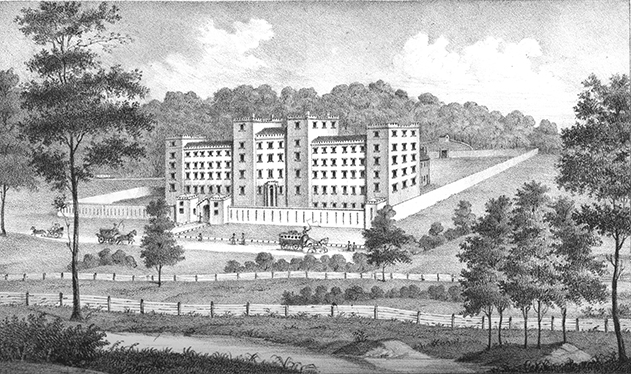

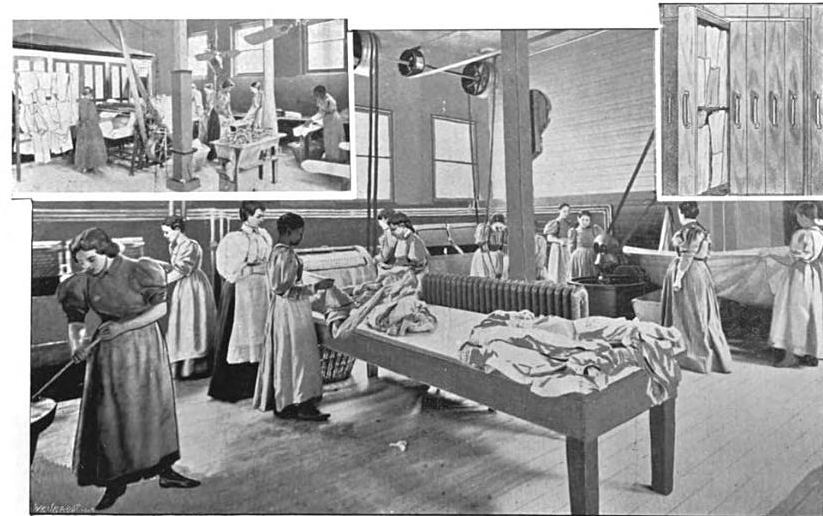

The Cincinnati House of Refuge opened in the autumn of 1850 in the Camp Washington area of Cincinnati, next to the spot where Cincinnati’s workhouse would be built more than a decade later. The House of Refuge was the beginnings of the establishment of a juvenile justice system in Cincinnati, and was something new to not only Cincinnati, but other American cities also. Previously, children and teenagers who had committed crimes were sent to adult penitentiaries. By the 1850s, Houses of Refuge, which focused on the reformation of children in a setting separate from adult offenders, existed in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston.[1] The design of Cincinnati’s House of Refuge makes clear that it was intended as a prison for children. A wall surrounded the building and the children were referred to as “inmates.” [2] In the spirit of a prison, the original act establishing the House of Refuge set a very strict daily regimen for the children. They were to work at least seven hours a day and attend school for at least three hours every day except Sundays and a few holidays including the Fourth of July, Christmas, and Thanksgiving. [3] Upon their entry into the House of Refuge, the children were assigned into different divisions by sex, age, and race. Each division had a separate school, sleeping areas, dining rooms, workshops, recreation rooms and playgrounds.[4]

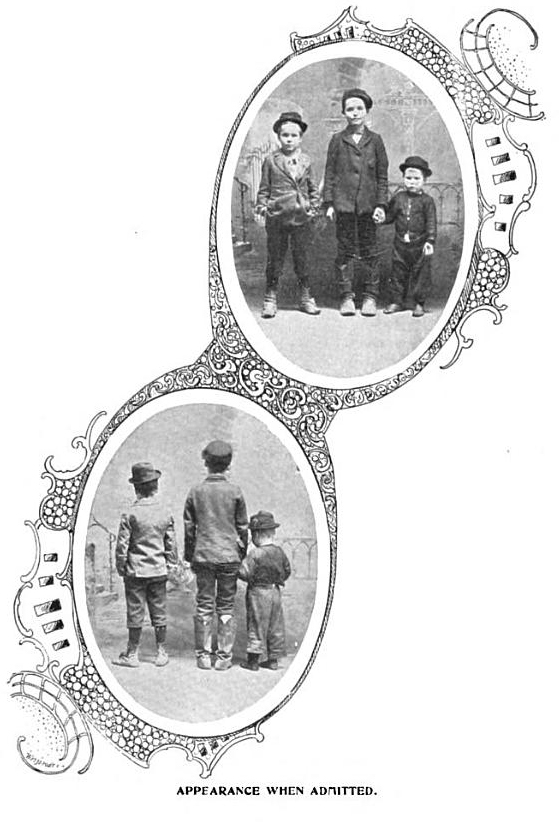

Three boys upon their arrival in the House of Refuge from the 1896 Annual Report of the House of Refuge

Early in the institution’s history, the majority of the children sent to the House of Refuge were accused of some sort of crime. According to the 1856 annual report, 208 boys and girls ranging in age from seven to seventeen were committed to the House of Refuge during that year. Most had been convicted of misdemeanor crimes or misbehavior including vagrancy, petit larceny, and insubordination, and nine were convicted of more serious offenses like burglary, arson, and assault. Only three were admitted for the lack of a home.[5] Over time, though, more and more children and younger children who were homeless or whose parents were not adequately able to care for them due to poverty, mental illness, substance abuse and many other reasons, ended up in the House of Refuge. By 1904, 139 of the 422 children or 32 percent of the children in the House of Refuge had been committed for non-criminal reasons including being dependent, homeless, “improper home,” neglect or “lack of a suitable home.” [6]

This situation was not unique to Cincinnati. During the nineteenth century, the United States became more urbanized and poverty became more visible, and many American cities were grappling with the question of what to do with children who had been abused, neglected, or those who were simply living in poverty. By the early 20th century, administrative staff at Cincinnati’s House of Refuge began to seek new ways to serve children who were just in need of stable homes.

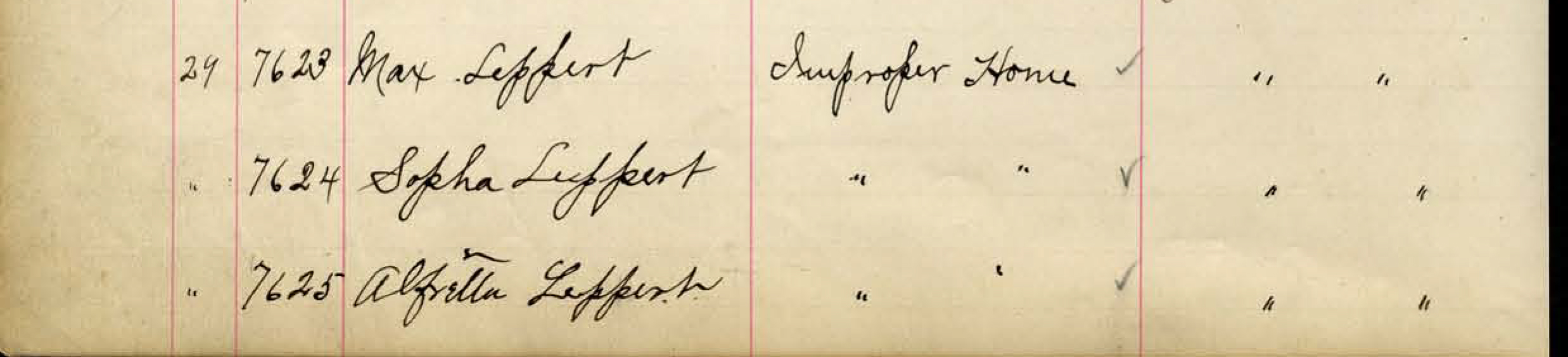

The Leppert children, ages 6, 10, and 2 were admitted to the House of Refuge in May 1895 for the lack of a proper home.

In December of 1912, Cincinnati City Council passed an ordinance authorizing a $250,000 bond to provide funds for a new institution for delinquent children in the “country” where boys and girls would be cared for on separate farms. At the same time, efforts were expanded to reduce the number of “dependent” children in the House of Refuge by either transferring them to the Children’s Home orphanage, by finding assistance for the families through relief or Associated Charities, by forcing parents to care for their children, and by working with the Hamilton County Juvenile Court to ensure that dependent children were sent elsewhere. [7] By 1916, the House of Refuge was closed.[8]

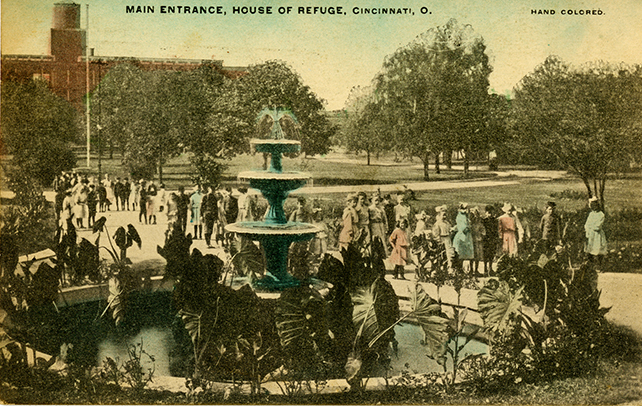

Main Entrance of the House of Refuge from the Florence and Nelson Hoffman Postcard collection, Archives and Rare Books Library

What remains of the records of the House of Refuge were transferred to the University of Cincinnati from the City of Cincinnati in the 1970s as part of the Ohio Network Local Government records program. The records are housed in the Archives and Rare Books Library on the 8th floor of Blegen Library. You can search the records online at: https://drc.libraries.uc.edu/handle/2374.UC/712586. To view the records in person or to learn more about the records contact us in the Archives and Rare Books Library by phone at 513-556-1959 or by email at archives@ucmail.uc.edu

_____

[1] For information on the history of the juvenile justice system, see: David S. Tanenhaus “The Elusive Court: Its Origins, Practices, and Re-inventions,” The Oxford Handbook of Juvenile Crime and Juvenile Justice, ed. Donna M. Bishop and Barry C. Feld (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), accessed 1 February 2016, http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195385106.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195385106/ and Donald J. Shoemaker, Juvenile Delinquency. (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013), 19-21. Accessed 01 February 2016. Proquest ebrary.

[2] Cincinnati House of Refuge, Sixth Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the House of Refuge (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Gazette Company Print, 1856).

[3] Cincinnati House of Refuge, The Charter, Rules and Regulations for the Government of the House of Refuge, Its Inmates, and the Bylaws of the Board of Directors (Cincinnati: Daily Times Book and Jobs Room, 1850), 10-11. Accessed 01 February 2016, Sabin Americana, Gale, Cengage Learning, http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY100406311&srchtp=a&ste=14.

[4] John Brough Shotwell, A History of the Schools of Cincinnati (Cincinnati: School Life Company, 1902), 419-425.

[5] Cincinnati House of Refuge, Sixth Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the House of Refuge (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Gazette Company Print, 1856), 16-17

[6] Cincinnati House of Refuge, Fifty Fourth Annual report of the Directors and Officers of the Cincinnati House of Refuge (Cincinnati: House of Refuge Manual Training School Printing Department, 1904), 11, Accessed 01 February 2016, Haithi Trust: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044100869387.

[7] Cincinnati House of Refuge, “Children’s House of Refuge.” Annual Reports of the Officers, Boards, and Departments of the City of Cincinnati (Cincinnati: City of Cincinnati, 1912), 277-278.

[8] Geoffrey J. Giglierano, The Bicentennial Guide to Greater Cincinnati (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Historical Society, 1988), 259.