BIOGRAPHY

EARLY LIFE & EDUCATION (1514-1530)

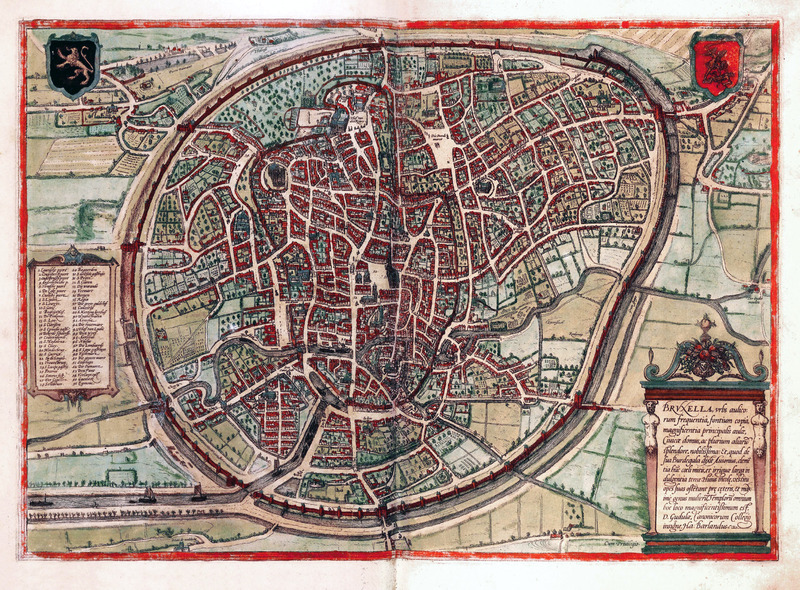

Andries van Wesel was born in Brussels on December 31, 1514 to Anders van W esel and Isabel Crabbe. Later, as a student, the young Andries Latinized his name to Andreas Vesalius, as was the custom for scholars and learned men of the period. [1] At the time of his b irth, the Holy Roman Empire’s House of Hapsburg ruled Brussels, which itself was part of a larger geo-political area called the Hapsburg Netherlands. The city of Brussels’s wealth came from its thriving textile and tapestry production, and trade. In addition, its intellectual reputation as a city with progressive educational ideals and institutions made it competitive with other European Renaissance academic bastions like Padua and Bologna in Italy. [2]

The Wesel family enjoyed a prosperous life as Vesalius’s father functioned as the personal apothecary to Margaret of Austria, who governed the Hapsburg Netherlands at the behest of her father, Holy Roman Emperor Maximillian I. For at least four generations, the men in Vesalius’s family practiced medicine and worked under a royal charge. His great grandfather, Johannes, became physician to Mary of Burgundy, wife of the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I, and also created significant wealth for the Wesel family as an investor. Everard van Wesel, Vesalius’s grandfather, was the royal physician to Emperor Maximilian I. And as stated above, Vesalius’s father Anders served Margaret of Austria, and later became valet de chambre or chamber valet for Emperor Maximilian’s son and successor, Charles V. [3]

[1] Andreas Vesalius of Brussels 1514-1564. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964) 28

[2] Andreas Vesalius: The Making, The Madman, and the Myth. (Persona Publishing, 2009) 14

[3] A Bio-Bibliography of Andreas Vesalius. (New York: Schuman’s, 1943), xxiv-xxv

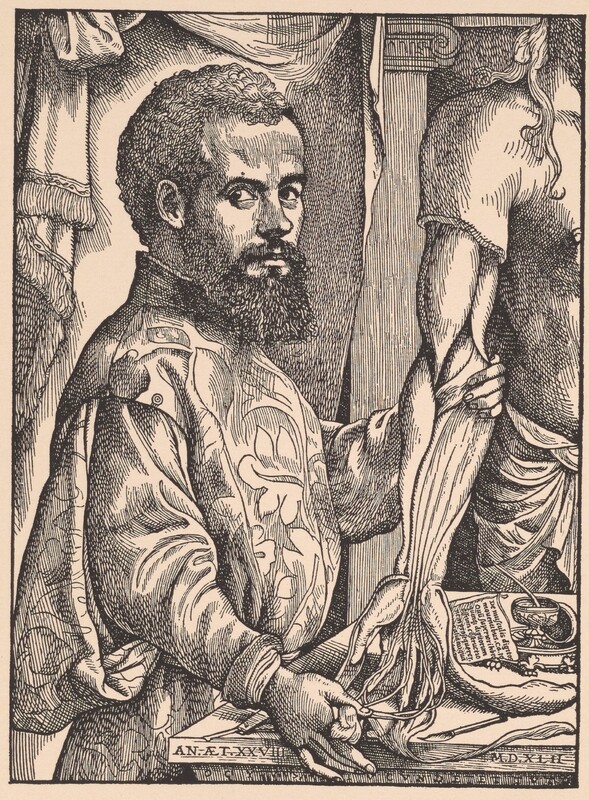

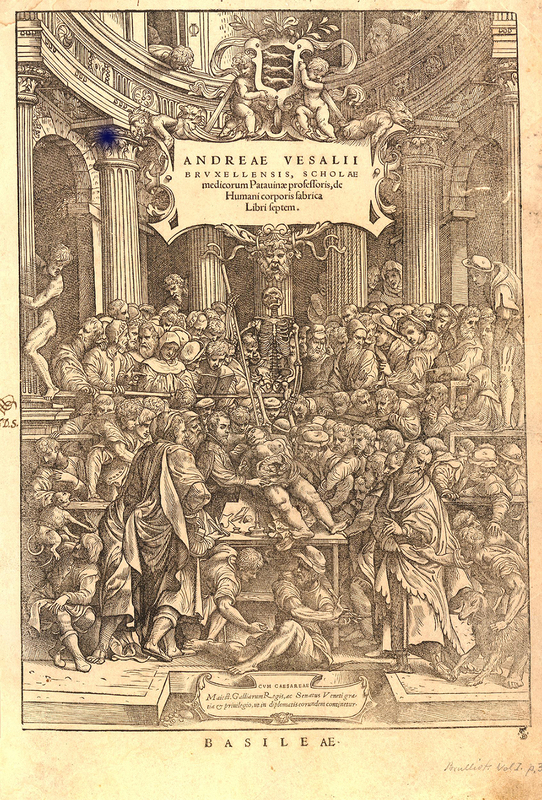

Portrait of Vesalius—Engraving created for the frontispiece of his work De humani corporis fabrica libri septem

Portrait of Vesalius—Engraving created for the frontispiece of his work De humani corporis fabrica libri septem--Artist: presumably by Jan Stephan van Calcar, 1543

Map of Brussels, 1500s

Map of Brussels, 1500s, Artist: Unknown, Courtesy Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Jewish National & University Library--Vesalius's family lived in the south eastern quadrant between the old wall and the newer outer wall surrounding the city.

Maximillian I

Portrait of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I--Artist: Albrect Durer, 1519, Courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum--Vesalius's father served as apothecary to Maximilian and later as valet de chambre to Maximilian's son and successor Charles V. Vesalius himself later served as a court physician to Charles V.

Portrait of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Portrait of Charles V, Oil on canvas, Artist: formerly attributed to Titian, 1548--Vesalius's father served as apothecary to Maximilian and later as valet de chambre to Maximilian's son and successor, Charles V. Vesalius himself later served Charles V as a court physician.

Valet de Chambre

Valet de Chambre—Artist: Abraham Bosse, from a series of etchings called La Metier or The Trades, 1635. Vesalius’s father Anders served Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, as a valet de chambre.

BROTHERS OF THE COMMON LIFE

Brussels’s renown as an intellectual center with high literacy rates, and many printers and book publishers, was in some part due to a religious sect known as the Brethren of Common Life. As a young boy, Vesalius’s father enrolled him in a school run by the Brethren where he learned Latin, and received introduction to the grammar, logic, and rhetoric trivium style of schooling.

The Devotio Moderna was a Roman Catholic religious movement founded in the Netherlands in the 14th century by Gerard Groote who, after a religious experience, preached a life of simple devotion to Christ. Eventually, like-minded followers formed communities known as the Brothers of the Common Life. The Brethren lived together in close-knit communities, giving up worldly goods to live chaste and strictly regulated lives in common houses. They devoted themselves to charitable work, nursing the sick, studying and teaching the Bible, and copying religious and inspirational works.

Because of their zeal to purify the Catholic faith of what they believed was the church’s moral decay, opposition to them was heavy. The movement gained momentum however and validity, finally gaining increasing approval by a succession of popes beginning with Pope Eugene IV (1431-1447).[1]

Most importantly for Vesalius, the Brethren founded a number of schools that became famous for their high standards of learning. A “who’s who” of northern European Renaissance thinkers attended these schools, including Nicholas of Cusa, Thomas à Kempis, and Erasmus, Martin Luther, and the Dutch Pope, Adrian VI.

[1] Van Geest, Paul. Gabriel Beel: “Brother of the Common Life ‘Alter Augustinus?’ Aim and Meaning of Tractatus de Communi Vita Clericorum.” Augustiniana Vol. 58, No. 3/4, 2008.

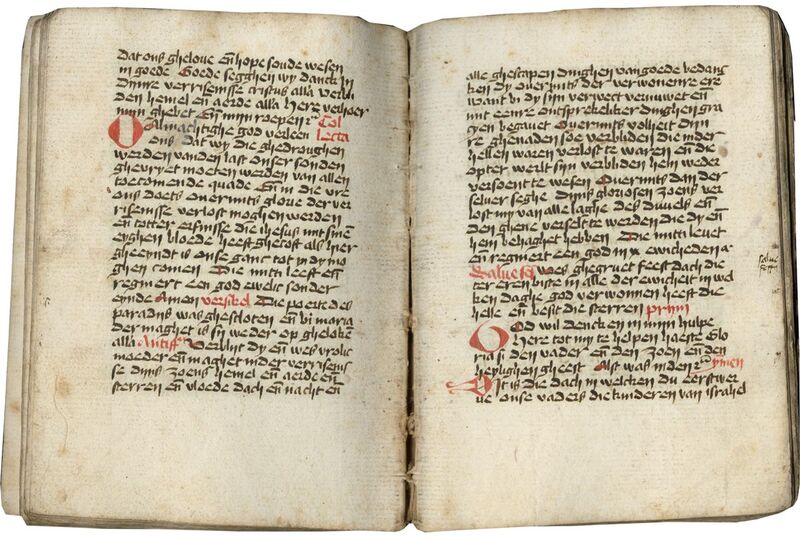

"Book of Hours"

Book of Hours— Courtesy Ghent University Library—Gerard Groote, founder of the Brothers of the Common Life, translated a Latin religious text into the vernacular. The image seen here is an illustrated version based on his translation. The status quo, whether religious, philosophical, or scientific, during the 15th and 16th centuries, came under increasing scrutiny. Groote set in motion a challenge to authority that Martin Luther later encapsulated in the Protestant Reformation.

Martin Luther

Portrait of "Martin Luther," Artist: Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1528, Courtesy of Kunstsammlung der Veste Coburg--Luther too received an education from the Brothers of the Common Life. The Devotio Moderna precursored the reformation movement Luther would lead in the first half of the 16th century.

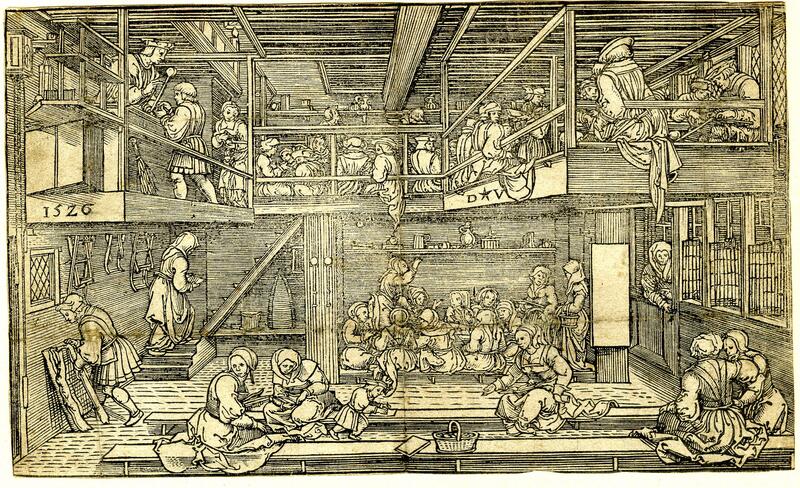

Low Countries School Room

School Room—Woodcut--Artist: Dirk Jacobsz Vellert, 1526, Courtesy British Museum—It is quite possible that in this woodcut the Netherlandish artist Vellert recreated a schoolhouse much like the one the young Vesalius attended while a child.

CASTLE COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF LOUVAIN (1530-1533)

In 1530, upon completing his education at the school of the Brethren, Vesalius followed the same footsteps as his grandfathers traveling 30 km east of Brussels to attend the University of Louvain. He was 15 years old. It was at Louvain that his great-grandfather Johannes taught, and that his grandfather Everard received his education.

Having learned Latin as a young boy, it was during his university education that Vesalius learned Greek and as he said “devoted [him] self to philosophy…” It was at Louvain too, that he became interested in medicine and began to show promise in illustrating. Regarding study of medicine at the time, it is impossible to overstress the import of the ancient physician Galen.

GALEN

Galen (129-c. 216 CE) from Pergamon (northwestern Turkey) was a Greek physician, anatomist, surgeon, and philosopher during the 2nd century CE. Considered one of the most accomplished of all medical researchers of antiquity, he served several emperors of Rome as personal physician. His views dominated Western medicine for more than 1300 years. During the early Renaissance, his texts were increasingly translated into Latin. The medical orthodoxy of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance held Galen in such high esteem, that to challenge any of his findings was nothing short of heretical.[1]

Whether Arab translations of ancient writing lingering on in post-Diaspora Spain, or Greek texts flooding into the West with Byzantines escaping the Ottomans, scholars excitedly and passionately poured over these newly discovered works, and the wisdom of classic thought held sway. Ancient answers by the likes of Plato, Aristotle, or Galen, et al., were likely the responses to current scientific and philosophical questions.

At Louvain however there were those who did not accept simply what the ancients said, but rather built on it and encouraged discourse on the ideas. Those teachers, like Nicolas Florenas, whom Vesalius later credited, made huge impacts on the young scholar to respect yet question classical sources.[2]

Vesalius completed his arts program at the University of Louvain and made plans to matriculate at the University of Paris to study medicine.

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Galen,” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galen (accessed October 20, 2021).

[2] Joffe, Stephen. Andreas Vesalius: The Making, The Madman, and the Myth. (Persona Publishing, 2009) 28.

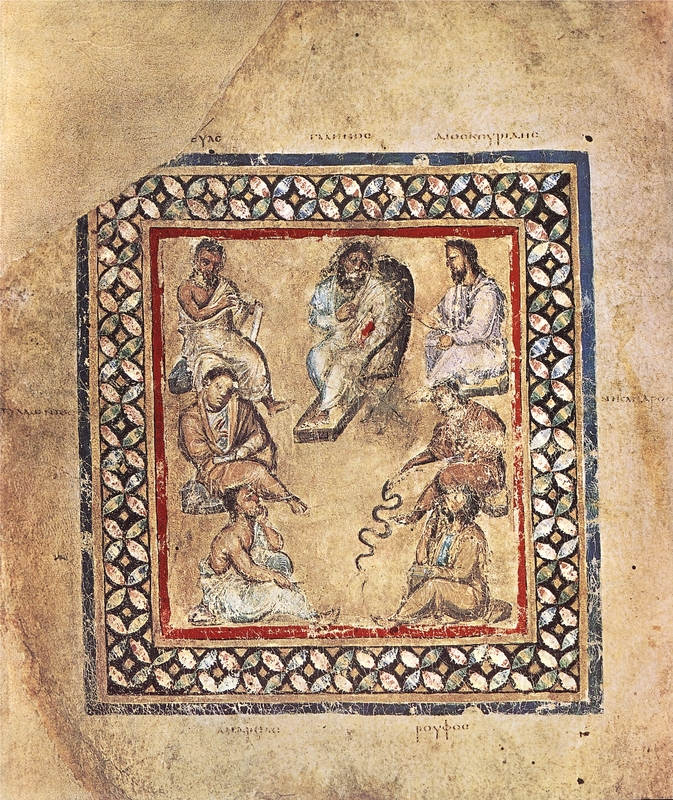

Vienna Discorides

Vienna Discorides—Early 6th-century Byzantine Greek illuminated manuscript in the original Greek by Dioscorides, Courtesy: Österreichische National Bibliothek—Important and rare example of a late antique scientific text--Seen here, Galen (top center), sits in a chair symbolizing his academic stature, while surrounded by six other famous Greek physicians. The Holy Roman Emperor purchased the manuscript in the 1550s.

UNIVERSITY OF PARIS (1533-1536)

In 1533, upon completion of his arts education at Louvain, Vesalius traveled to Paris to begin medical study with its Faculty of Medicine at the University of Paris. The program consisted of a four-year curriculum leading to a Bachelor of Medicine.[1] His coursework included Materia Medica (literally “medical material,” the body of collected knowledge about the therapeutic properties of any substance used for healing)[2], Pharmacy, Physiology (study of the mechanisms that work to keep the human body functioning), Pathology (study of the causes and effects of disease and injury) and Surgery (the manual/instrumental treatment of disease and injury).[3] Lecturers introduced students to the principle ancient texts of Hippocrates, Avicenna, Rhazes, et al, and of course Galen. Not taught as medical history, the aforementioned authors’ works were revered with a contemporary immediacy and taught as training manuals.

VESALIUS’S EARLY DISSECTIONS

In Paris, Vesalius adopted Galen’s belief that physicians discover truths by empirical observation and hands-on investigation. Fittingly then, what he did out of class became as important as what he did while attending lectures. Since little human dissection occurred at the university, he and other students gathered bones of those buried in mass plots and on at least one occasion robbed a grave for personal study and dissections on their own time. Vesalius later recalled “spending long hours in the Cemetery of the Innocents in Paris turning over bones."[4]

So esteemed were ancient physicians that it was thought dissection would do little more than prove their theories. What dissection occurred usually happened once annually in the basement of the Hotel de Dieu (Hospital). What took place at all other times often was animal dissection and/or vivisection (dissection performed on live animals), or the dissection of a particular human body part, appendage, or organ. [5] Vesalius’s skills at dissection grew during this time eventually leading to an offer to function as a “demonstrator.”

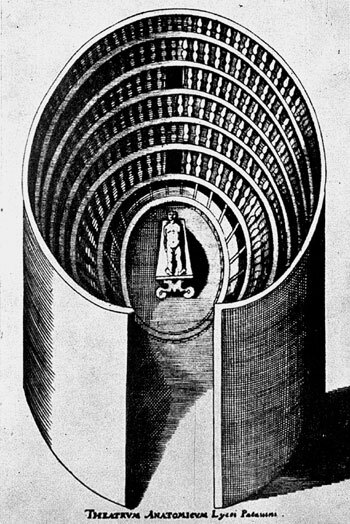

At the time, three persons accomplished a dissection: the physician/instructor, who usually sat above the proceedings reading from a classic text; the demonstrator, sometimes a barber-surgeon, who performed the incisions; and the ostensor, who with a pointer indicated to the students the positon of the anatomy.[6]

DISSECTION AND THE CHURCH

Though no formal Catholic Church doctrine ever prevented the dissection of human bodies, it is thought that Pope Boniface VIII’s papal bull of 1300 titled De Sepulturis, that forbade the boiling of bodies to remove skin from bone, provided the reason for the confusion surrounding whether or not the Catholic Church banned dissection.[7] By the 1500s however, especially in northern Italy, dissection was not only practiced, but anatomy increasingly was seen as being a distinct discipline and fundamental to surgery. Both university towns of Bologna and Padua, cities in which Vesalius later made a name for himself, were epicenters for dissection with no recorded interference from church officials.[8]

THE ITALIAN WAR 1536-1538

In Vesalius’s third year of study, conflict broke out between France and the Holy Roman Empire (HRE). King Francis I of France attacked the Duchy of Milan, a territory controlled by the HRE. In retaliation, Emperor Charles V attacked Provence in southern France. Paranoia reached fever pitch when Charles V’s Belgian forces assembled on the border of what is now Belgium and northern France. Vesalius’s Belgian heritage and his father’s role as Charles V’s personal apothecary became too great a liability and he chose to leave Paris and return to the University of Louvain to finish his studies. [9]

[1] Joffe, Stephen. Andreas Vesalius: The Making, The Madman, and the Myth. (Persona Publishing, 2009) 32.

[2] Wikipedia contributors, "Materia medica," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Materia_medica&oldid=1041042748 (accessed October 20, 2021).

[3] O’Malley, C. D. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels 1514-1564. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964) 40.

[4] Joffe, Andreas Vesalius, 53.

[5] ibid., 36.

[6] Wilson L. William Harvey’s Prelectiones: The Performance of the Body in the Renaissance Theater of Anatomy. Representations (Berkeley) 1987;17:62–95. doi: 10.1525/rep.1987.17.1.99p0423c. [PubMed].

[7] Thadani, Krishan M. “The Myth of a Catholic Religious Objection to Autopsy: The Misinterpretation of De sepulturis during the Renaissance.” The National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly. Spring 2012, 39.

[8] Ibid., 40.

[9] Joffe, Andreas Vesalius, 57.

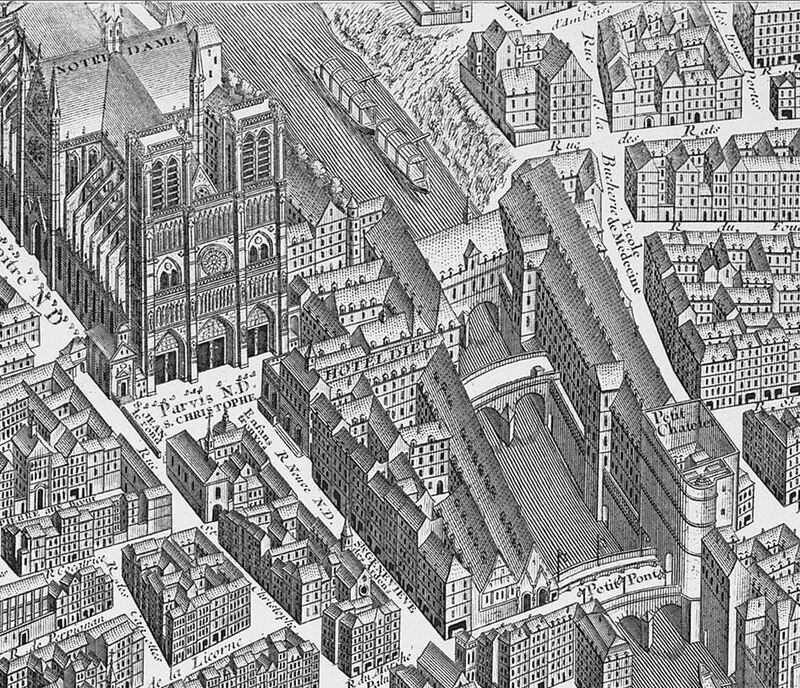

Hotel de Dieu

Detail image is from the Plan of Turgot, 1739, Courtesy Norman B. Leventhal Map Center—Commissioned by the Mayor of Paris, Michel-Etienne Turgot, drawn up by Louis Bretez, and engraved by Claude Lucas, the Plan of Turgot detailed the city of Paris in the 1730s. The Hotel de Dieu (hospital) sat directly across from Notre Dame Cathedral and was home to Paris’s annual dissection.

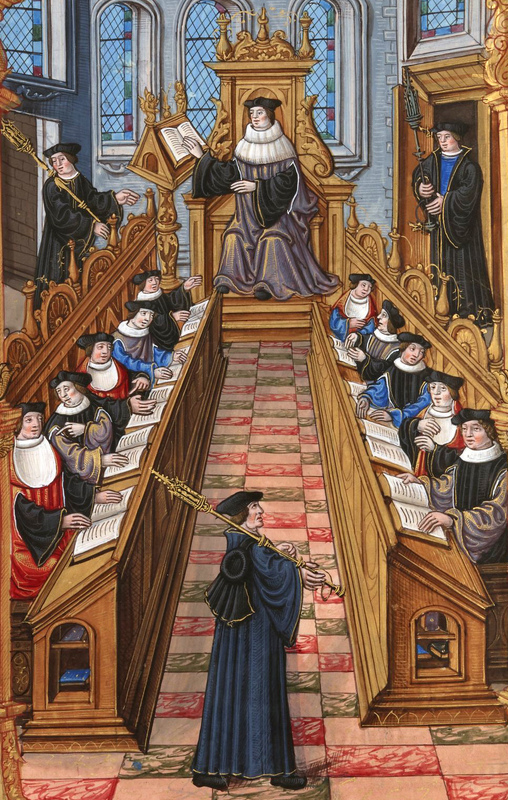

"Meeting of Doctors at the University of Paris"

Meeting of Doctors at the University of Paris, 1537, from the "Chants royaux" manuscript, Artist: Etienne Colaud, Courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

Engraving depicting the Saints Innocents Cemetery in Paris, c. 1550

Engraving depicting the Saints Innocents Cemetery in Paris, c. 1550—Artist: Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer, 1890, Courtesy Private Collector—The cemetery took its name from the Church of the Holy Innocents that stood beside it. Vesalius and his colleagues would steal bones from the cemetery to study, and attempt to construct full-skeletons.

Truce of Nice

Truce of Nice, Artist: Taddeo Zuccari, 1538, Courtesy Sala del Consiglio. Palazzo Ducale—Pope Paul III stands between Francis I and Charles V. Francis and Charles hated each other so much, they refused to sit in the same room during negotiations to end the 1536-1538 Italian War. Pope Paul III, the mediator, traveled room-to-room delivering personal messages to each. Because of the war that preceded this truce, Vesalius fled Paris and returned to Louvain.

LOUVAIN, PADUA & TABULAE ANATOMICAE SEX (1536-1542)

In 1536, Vesalius returned to the University of Louvain to finish his medical studies. His reputation followed him as a dissector because upon his return, he performed the first dissection (an executed criminal) in Louvain in almost twenty years.[1]

Vesalius’s bachelor of medicine degree necessitated the completion of his thesis: Paraphrase of the 9th book of Rhazes’ Almansor. It became his first publication in 1537. The Arab–Persian physician and alchemist Rhazes (854–925) played more than a passing role in the young student’s life. Vesalius’s great-grand father Everard wrote a commentary on Rhazes’ Almansor and it is probable that Vesalius possessed those commentaries at the time of his thesis work.[2]

In his thesis, he attempted to smooth the rough 1481 translation of Rhazes’ work on therapeutics, and also systematize the medical terminology contained therein. In addition to Latin, medical terminology in Renaissance Europe often confusingly was found in Arabic and Greek as well.[3] Though only paid passing attention in many Vesalius biographies, author Stephen Joffe notes that the Paraphrase reflects Vesalius’s “bold ambition, impudent self-confidence and exhaustive desire to achieve excellence.”[4]

UNIVERSITY OF PADUA

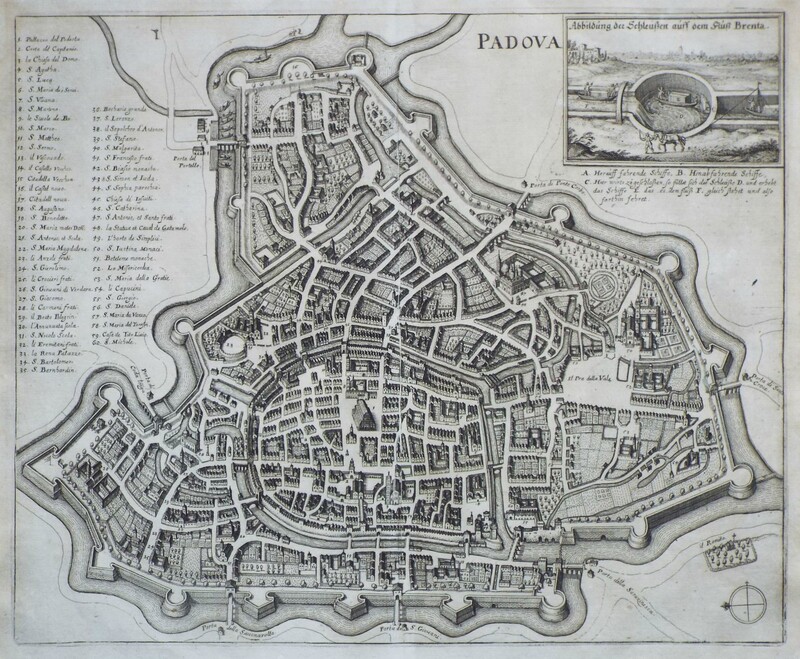

In 1537, Vesalius traveled to Padua Italy to continue his education. For a young scholar in Europe, the University of Padua with its diversity and intellectual freedom offered a wealth of opportunity, and attracted the best and brightest scholars in Europe.[5] Important to Vesalius, the University of Padua served as a center for dissection and anatomies had taken place there at least since the 1300s.[6]

He matriculated at the university seeking a doctoral degree in medicine and demonstrated such superior understanding of it and anatomy that within a year his instructors granted him an early doctoral defense and graduation. The day after his doctoral exams, he performed Padua’s winter-term anatomy demonstration and immediately became chair of surgery and anatomy at the university. [7]

Unlike the traditional methods of dissection with physician, surgeon, and ostensor, Vesalius worked alone. He supplemented his dissections however with charts, drawings, illustrations, dissected animals, and skeletons. [8]

TABULAE ANATOMICAE SEX

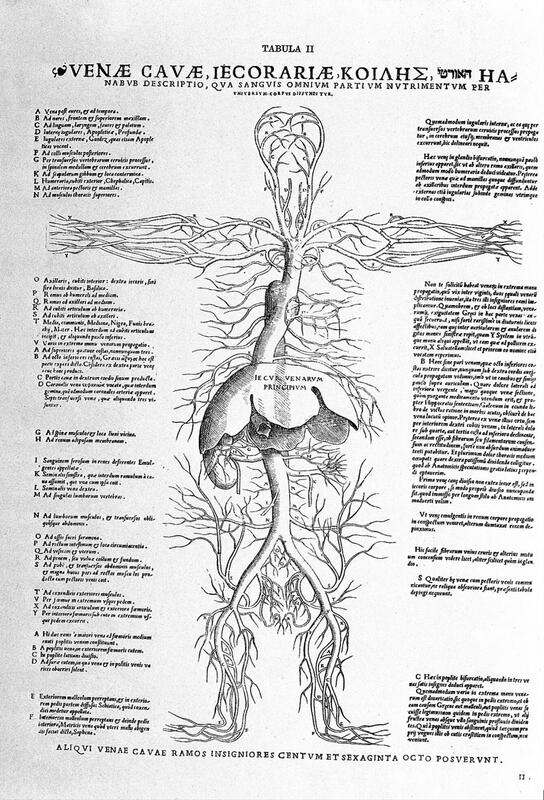

Along with a Belgian artist now living in Venice, named Jan van Calcar, Vesalius refined his dissection demonstration drawings turning them into his second publication Tabulae Anatomicae Sex (Six Anatomical Tables). Printed on large sheets, with one wood-cut block illustration per sheet, Vesalius and Calcar’s images were the largest ever printed by European printers up to that point.

Vesalius designed the book for students and it became a best seller. Because of this, very few copies survive, as the books were quite literally used to death.[9]

"You, the audience, look closely at these images. Let yourself be drawn into them, as I am when I find them in the flesh. See how fascinating my world is and see how you, who have never seen, now know that which was unknowable in yourself."

[1] Joffe, Stephen. Andreas Vesalius: The Making, The Madman, and the Myth. (Persona Publishing, 2009) 68

[2] Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, medici Caesarei Epistola, rationem modumque propinandi radicis Chynae decocti (Basel: Joa. Oporinus, 1546), 196

[3] Ambrose, Charles T., "Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564)–An Unfinished Life" (2014). Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics Faculty Publications. 65. 218 https://uknowledge.uky.edu/microbio_facpub/65

[4] Joffe, Andreas Vesalius, 72

[5] ibid., 73

[6] O’Malley, C. D. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels 1514-1564. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964) 74

[7] Joffe, Andreas Vesalius, 77

[8] ibid., 83

[9] ibid., 86

DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA (1543)

While teaching in Padua and lecturing in Bologna and Venice, Vesalius made important friends like the Medici family. He also made not a few enemies out of his academic peers. The reason: his teaching, dissecting, and intellectual style broke with Galenic tradition. Not only, did he dissect differently than Galen, he had the audacity to disagree with him.

Vesalius’s ideas on bloodletting also riled many of his colleagues. He believed in letting blood as everyone did, but he disagreed where incisions should occur in a vein. The real sin however occurred in Vesalius’s arguing from the perspective of observation and hands-on anatomy rather than simply trusting ancient sources.

There is very little offered to the [students] that could not be better taught by a butcher in his shop.

In 1540, Vesalius took leave from the University of Padua to begin work on what became his masterpiece. In it, he intended to examine every aspect of Galen’s anatomical descriptions, to confirm if true or to correct when wrong. Anatomy, he believed, was fundamental and should underscore all medicine. Perhaps that is why he titled this work, Fabrica. Regardless of why the book took the title it did, Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem changed forever how anatomy was studied and performed.

ILLUSTRATION

Vesalius included 400 illustrations of all body parts inserted into the text as visual reference materials.[1] Because no credit was given, the artists who created the illustrations are unknown. It is safe to assume however because of his prior relationship with Stefan van Calcar, Vesalius hired the Venetian artist again, at least for the larger illustrations.[2] The famous Venetian artist Titian maintained a workshop in Venice, and it is generally held that whoever accomplished the illustrations emerged from this group. Regardless, Vesalius called on the best artists to accomplish his task.

[ILLUSTRATION--Inset] Today, we see the illustrations function not just as anatomical tables, but also with all of the attributes of Renaissance art: landscapes, perspective, focus on the human and the individual, and finally the memento mori.

Before printing, illustrations were cut into woodblocks. At the time, Venice not only produced painters of note, but also many of the finest woodblock artisans.[3] In fact, much of the money Vesalius spent on the project went into the production of the 400 illustrations and the cutting of the requisite woodblocks.[4]

PRINTING

Vesalius crated his manuscript and woodblocks and sent them over the Alps to Johannes Oporinus, a highly reputable printer in Basel with whom he had previously worked. Vesalius also sent blocks and text for the creation of another shortened version of the Fabrica to be created for students called the Epitome. The author worked closely with Oporinus during the process as the note the Vesalius sent along with the manuscript suggests.

“You will shortly receive…together with this letter, the plates engraved for my De humani corporis fabrica and for its Epitome. I hope they…reach Basel safely and intact…I shall…come to you soon and remain at Basel, if not through the entire printing period, then at least for some time.”

REACTION

Printing ended in the summer of 1543 and the work became an immediate success. Booksellers sold out, and copies traveled the continent and to England. If Vesalius wasn’t already known for his scholarship he was now. Vesalius’s writing style with its highly polished classical Latin exhausted readers even of the day. In fact, later Vesalius biographer Harvey Cushing wrote that “as a book [it] has been more admired and less read than any publication of equal significance in the history of science.”[5]

The work, its scope, its imagery, and its break with religious adherence to Galenic anatomy could not be ignored. In fact, all anatomy that followed Vesalius and the printing of his Fabrica would deal with him in some capacity, so much so that anatomy prior to the Fabrica is now referred to as “pre-Vesalian.”

[1] Joffe, Stephen. Andreas Vesalius: The Making, The Madman, and the Myth. (Persona Publishing, 2009) 124

[2] Ibid., 124

[3] Ibid., 134.

[4] Ibid., 140.

[5] Cushing, Harvey. A Bio-Bibliography of Andreas Vesalius. (New York: Schuman’s, 1943), 81.

Title Page of the Fabrica

Title Page of the Fabrica— Artist: Most likely Jan Stefan van Calcar, 1543, Courtesy The Trustees of the British Museum—No ostensor, no barber, and no seated Galenist reading from an ancient text. The illustration shows an anatomy theatre where Vesalius stands left of center at a table dissecting alone a woman’s abdomen, a large crowd gathered, a human skeleton behind the dissected body, a monkey in lower left and two dogs [animals quite likely to be used in vivisection] in lower right.

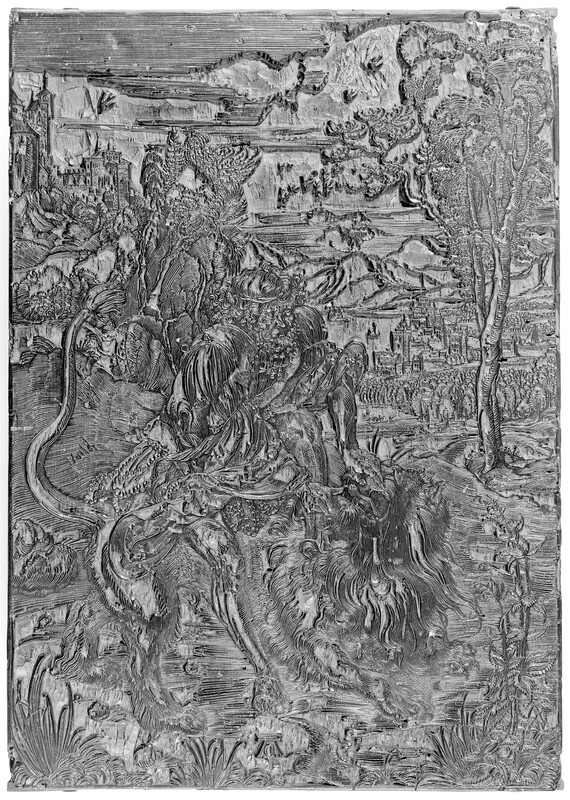

Woodblock for Samson Rending the Lion

Woodblock for Samson Rending the Lion—Artist: Albrect Durer, 1498, Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art—Though not from the Fabrica, the wood printing block shown here exemplifies the remarkable amount of detail that went into its creation.

Johannes Oporinus

Johannes Oporinus--Artist: presumed to be Hans Bock, c. 1585, Courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel—A scholar, Oporinus held the chair of Greek language at the University of Basel. He opened a print shop specializing in classical texts and their translations. Once, arrested and imprisoned for printing a Latin translation of the Koran, Martin Luther came to his aid reassuring Basel city officials that printing the Koran could only benefit Christianity, not harm it. The Fabrica would be his best-known printing.

The Printer’s mark of Oporinus

The Printer’s mark of Oporinus—Courtesy BEIC Digital Library. Oporinus’s mark shows the mythological lyre player Arion of Lesbos, who is supported by a Dolphin on the sea.

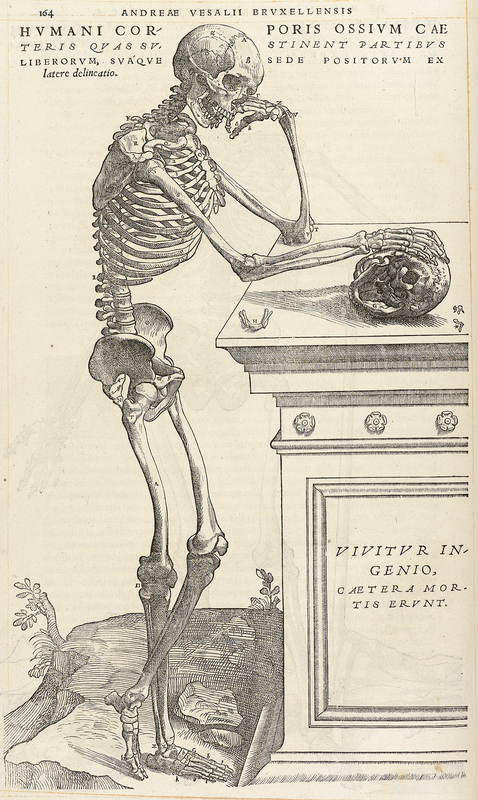

Plate from the Fabrica

Plate from the Fabrica—Courtesy Wellcome Collection—In this memento mori, one skeleton considers the skull of another. The Latin inscription on the cartouche reads “genius lives, all else is mortal.” Perhaps with this phrase, Vesalius patted himself on the back.

COURT PHYSICIAN & SPAIN (1543-1564)

IMPERIAL POSITION

In 1544, upon the success of the Fabrica, Vesalius, following family tradition, successfully applied to Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire for service as Medicus Familiaris Ordinaries, or “physician to the household” within the Emperor’s Court. He served the Emperor for the next 13 years in a position requiring much more than anatomies and dissections.[1]

After a four-year truce, war again broke out between France and the Emperor. Charles sent Vesalius to the front to care for the army’s commanders. There he worked under the charge of the Spanish physician, Daza Chacon. As a battlefield surgeon, Vesalius primarily performed amputations and cauterizations.[2] Not used to working with living specimens, Vesalius proved not as shrewd a battlefield surgeon as he was an anatomist. In fact, Chacon recounts in a letter Vesalius struggling to amputate an arm below the elbow.[3]

During a break in fighting and with the Emperor’s permission, Vesalius ventured to Pisa at the invitation of Cosimo de Medici. The Emperor allowed the trip as he hoped to gain favor with the moneyed ruling family of northern Italy.[4]

DESTRUCTION OF HIS WORK

Vesalius’s successful anatomy demonstrations at Pisa to crowds numbering as large as 500, garnered another petition from Cosimo Medici to the Emperor, this time to allow the physician to stay on at the University in Pisa as professor. The Emperor denied the request; so Vesalius left Italy to rejoin Charles in Germany. Prior to this reunion, however, Vesalius burnt all of his research and writing in a rage. Though scholars speculate as to the reason, Vesalius’s own words suggest it was done out of impatience with his detractors and the Emperor.[5]

Also during this time, he married, built a home in Brussels, had a child, and with time became a competent surgeon and physician, discovering aneurisms, predicting brain injuries, and much more.

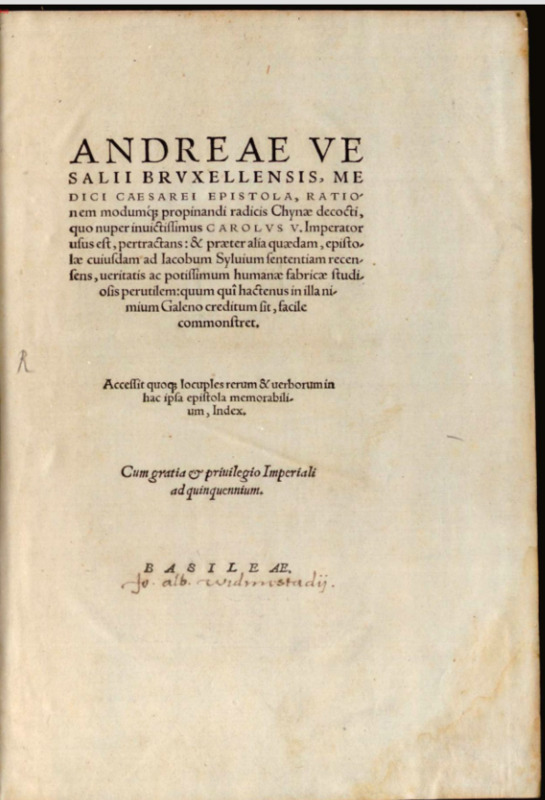

CHINA ROOT EPISTLE

After the war, he cared for Charles V’s ailments as court physician. The Emperor suffered from gout and treated it with an herb known as China Root. Skeptical of its curative features, Vesalius penned a letter to a botanist to learn more about it. That he wanted this letter published (as it eventually was) is obvious because in it he addresses some his attackers on other subjects, e.g., his perceived anti-Galenism. [6]

SPAIN & DEATH

Phillip II succeeded Charles V and as a Spanish Hapsburg ruled from Spain. Vesalius maintained his position in the court and traveled with him. The physician found Spain academically stifling and militantly orthodox in its Inquisition-era Catholicism. Its medical community, for example, still relied on astronomical charts and forbade dissection.

Vesalius desired to return to the academic freedoms of the University of Padua. In 1564, however, he left Spain on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Conjecture abounds as to why the trip happened. Recent discoveries in Spain support the proposition that Vesalius made the trip on behalf of Phillip II carrying financial aid to Christian churches in the Holy Land. Much more interesting, though never proven are accounts holding that the pilgrimage came as penance for Vesalius who accidentally began a dissection on a still-living subject. [1]

[1] O’Malley, C.D. “Andreas Vesalius’ Pilgrimage.” Isis Vol. 45, No. 2 (Jul., 1954), pp. 138

His return trip would take him through Venice. Being in northern Italy before the start of a new academic year implies that perhaps Vesalius may have taken a position at the University of Padua against the Emperor’s orders.

En route to Venice, a shipwreck left Vesalius on the Greek island of Zakynthos. There, he contracted an illness and died. Though given burial on the island, Vesalius’s burial site was lost soon after his interment.

[1] O’Malley, C. D. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels 1514-1564. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964) 189.

[2] Van Hee, Robrecht. “Andreas Vesalius: His Surgical Activities and Influence on Modern Surgery.” Acta Chirurgica Belgica. 116. 62-68. (2016).

[3] Daza Chacon D. Pratica y teorica de cirugia enromance y en latin. Madrid: Lucas Antoniode Bedmary Valdivia; 1678

[4] Joffe, Stephen. Andreas Vesalius: The Making, The Madman, and the Myth. (Persona Publishing, 2009) 165

[5] Ibid., 178.

[6] Ibid., 183.

Emperor Charles V at Muhlbert

Charles V sits victoriously on his horse after defeating the French at the Battle of Muhlberg

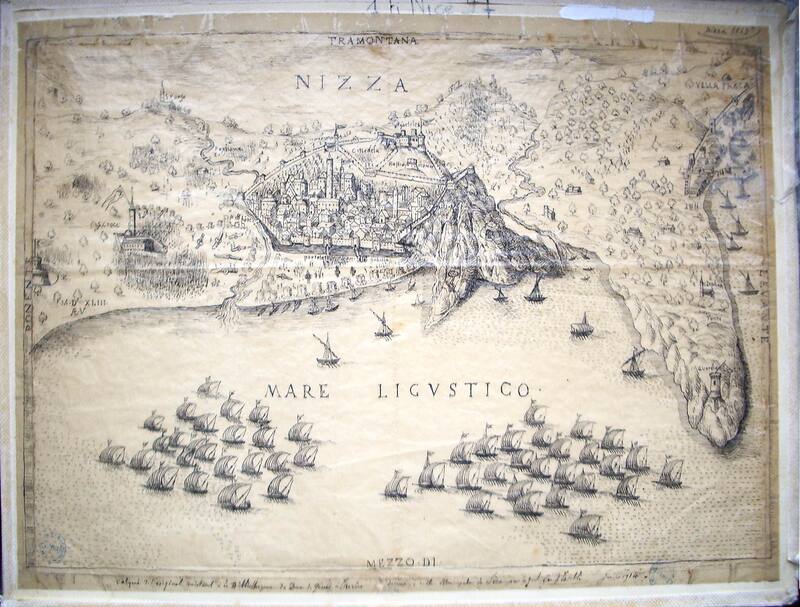

Siege of the Ottoman and French fleet of Nice in 1543

Drawing, Siege of the Ottoman and French fleet of Nice in 1543—Artist: Toselli after an engraving by Aeneas Vico. Courtesy Archives Municipales de Nice

Dionisio Daza Chacón at age 60

Woodcut portrait of Dionisio Daza Chacón at age 60, Artist: Unknown, Courtesy National Library of Spain.

Title page of the China Root Epistle

Title page of the China Root Epistle—Printed by Oporinus. Image Source: books.google.com.