LOOKING EAST

William Howard Taft and the 1905 U.S. Diplomatic Mission to AsiaThe Photographs of Harry Fowler Woods

Double Exposure

by Jeffrey Harrison

My great-grandfather’s photo albums

from his trip around the world in 1905,

their suede covers printed with his name

in gold capitals, and their brittle pages

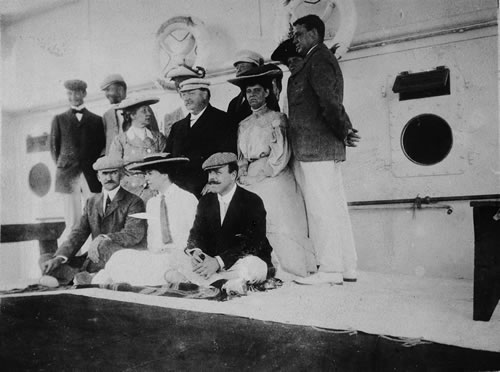

torn loose and out of order, show him

in the Philippines with William Howard Taft

(round as the world, big as an elephant),

then on an elephant in India,

wearing a pith helmet and staring out

from behind his black, indelible moustache

as if he owned the world…

a world

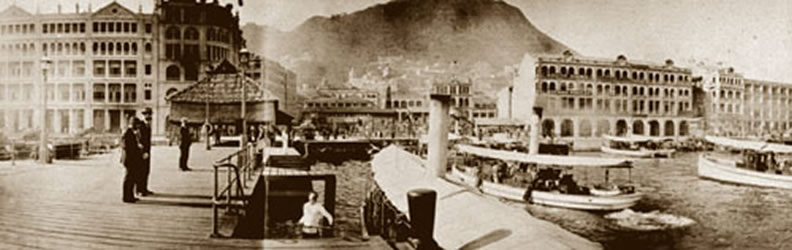

I can’t recognize (Hong Kong’s bristling

crystallization of skyscrapers

dissolved to a sediment of shacks),

and a man I never knew, with whom

I feel no bond beyond the facts

of my middle name and an inheritance

of genes now reshuffled as

these pages I turn.

But wait! Here’s one

of Varnasi, just as I saw it

a year ago—and all at once I’m looking

with his eyes through the viewfinder

of his camera with the black bellows extended,

then letting it fall and feeling its weight

against the back of the neck as the scene

just caught on film—a body in flames

crumpling as the pyre underneath it

collapses—burns itself into the brain

which can’t contain it, can’t stop the fire

from spreading through all the internal organs

and into the limbs, until the knees give way

and he has to sit down.

He sits there

for a long time, dazed, not sure what has happened,

then gets up and leaves me on the stone steps

in the exact spot he rose from, while he

wanders off along the ghats, ghost-like,

in the shadows of temples piled like stalagmites,

to join the multitude of spectral figures

who have traveled here for centuries,

disappearing behind a hazy veil

of smoke rising from the funeral pyres

and the emulsion’s silvery sheen.

Woods (left) and friend in studio

HARRY FOWLER WOODS (1859 – 1955)

Born in Cincinnati, Harry Fowler Woods was the son of William K. Woods and Elizabeth Martin Sharp Woods. In 1880 Woods joined Chatfield and Woods, a paper company founded by his father and his uncle, William H. Chatfield. Harry became the president of the company in 1918, and served in that capacity until 1928 when he became chairman of the board, a position he held until 1951. Harry Woods married Katharine Longworth Anderson with whom he had three daughters and a son. Katharine was the great grand-daughter of the first Nicholas Longworth, land speculator and one of the wealthiest men of his time. She was also a cousin of Congressman Nicholas Longworth.

During his long life, Harry Fowler Woods’s extensive travels included the 1905 diplomatic trip to Asia, which Woods followed with a tour of Indochina, Burma, India, Egypt, and Greece where he took over four hundred additional snapshots. Not long after the Asia trip, he purchased a camp in New York’s Adirondack Mountains where he spent most of each summer fishing and exploring in the well-known Adirondack guide boat. Woods was an avid and talented amateur photographer. His 1905 photographs of the Taft mission were among the intriguing artifacts that he left at Woods Camp for future generations to enjoy. He died in 1955 at age 95.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE HAND-HELD CAMERA

The Woods photography albums depict scenes in San Francisco, Honolulu, Japan, the Philippines, and China. Viewed from a historical perspective, some of the photographs define this unique moment in Chinese and U.S. history, which marked the end of the European colonial empires and the dawn of an era of American imperialism. These photographs also represent an early use of photography as a documentary form employing the hand-held camera, which had only recently come on the market. Often featuring spontaneous images that the new cameras made possible, the Woods collection may be as important as the official, frequently staged or ceremonial photographs, taken during portions of the trip by the well-known official photographer, Burr McIntosh. The China images can be considered unusual not only because they furnish documentation of the official U.S. diplomatic trip, but also because they provide a Westerner’s perspective through images of people and places, many of which no longer exist.