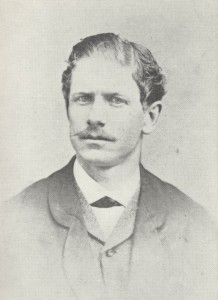

Ambrose Gwinett Bierce was born on June 24, 1842 in Meigs County, Ohio. The youngest of ten siblings of Marcus Aurelius and Laura Sherwood Bierce, he did not have a strong bond with his father and mother while growing up and left his family in 1857 to become a printer’s devil for The Northern Indianan newspaper in Warsaw, Indiana for short period of time before eventually returning to Ohio to live with his uncle, Lucius Verus Bierce.

In 1859, at the age of seventeen, Bierce attended the Kentucky Military Institute for a period of one year before dropping out. His interest in the military led him to enlist in Company C of the 9th Regiment, Indiana Volunteers in April of 1861 shortly after the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Initially enlisted in the 9th Regiment as a private, Bierce would rise to the rank of sergeant before finally being promoted to the rank of brevet captain and topographical officer under the command of General William Babcock Hazen of Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio.

During his tenure as a topographical officer, Bierce surveyed and fought in some of the greatest battles of the Civil War: Battle of Shiloh, Battle of Stones River, Battle of Chickamauga, Battle of Missionary Ridge, Battle of Pickett’s Mill, and Battle of Kennesaw Mountain.

It was during the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain that Bierce was wounded in the head by a Confederate sniper and evacuated to a military hospital in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Bierce would later recollect often in his writings about the head wound, stating at one point, that his head had “broken like a walnut.” Eventually, through a combination of the head wound and a resentment toward the death and destruction of the American Civil War, the cynical side of Bierce would emerge that would become his claim to fame as a writer.

Deemed unfit to continue fighting, Bierce was mustered out of the military in Huntsville, Alabama in January of 1865. Shortly after the Civil War ended, Bierce took a position as a Federal Treasury agent in Selma, Alabama overseeing the shipment of cotton. Eventually becoming fed up with the corruption surrounding the cotton shipments, Bierce resigned his Treasury post and returned to Indiana to apply for a captaincy in the United States Army.

While his request for captaincy was being processed, Bierce joined General Hazen in the summer of 1866 as an engineering attaché in a military expedition through the Indiana territory to inspect Western military posts. The military expedition slowly made its way to San Francisco, California and by the fall of 1866 it was here that Bierce learned that his application for captaincy had been denied. Frustrated with the military experience, Bierce was honorably discharged as a brevet major and took a position as a watchman at the United States Branch Mint.

The watchman position at the United States Branch Mint did not prove worthwhile and it was then that Bierce decided on a career in journalism. Bierce the cynic, or “Bitter Bierce” as he would later be called, procured a writing position as the “Town Crier” and editor for the San Francisco News Letter by the end of 1868. It was while at the News Letter that his wicked wit and fame began to rise on both the local and national level. This rising fame caught the attention of Marie Ellen (“Mollie”) Day, a San Franciscan socialite, and led to his courtship of and marriage to her in 1871.

A wedding gift from Mollie’s father took the newlywed couple to England. While in England, Bierce enjoyed one of his most prolific periods as a writer. He was able to earn a wage working for Tom Hood’s humor magazine Fun under the pseudonym “Dod Grile” while continuing his “Town Crier” column in the magazine Figaro. He also wrote his first three books while in England: Nuggets and Dust (1872), The Fiend’s Delight (1873), and Cobwebs from an Empty Skull (1874). And during their time in England, Ambrose and Mollie gave birth to their first two children, Day (1872) and Leigh (1874).

Although Bierce was content in England in his professional life, it was his family life (and mother-in-law) that were causing him stress. In the spring of 1875, he sent Mollie and the children home to San Francisco before rejoining them later in the fall of that year. Shortly after his return home, Bierce was greeted with the birth of his third child, Helen.

In 1877, Bierce started up his “Prattle” column in The Argonaut while simultaneously overseeing the newspaper as an associate editor. Toward the end of decade Bierce relocated to San Rafael, Marin County, California before moving to South Dakota to pursue a mining venture as a general agent of the Black Hills Placer Mining Company. When the company became insolvent and the venture proved a failure, Bierce returned to San Francisco in the spring of 1881 and took up an editorial role with the Wasp where he resumed his column “Prattle” and began contributing a series of definitions in a column titled “The Devil’s Dictionary.”

Throughout the early half of the 1880s Bierce relocated numerous times around the central California region before settling in St. Helena, Napa County, California in 1885. A year later, Bierce made his last contribution to the Wasp and was shortly thereafter hired by William Randolph Hearst as a columnist and editorial writer for the San Francisco Examiner. In March of 1887 Bierce resumed his “Prattle” column and also began publishing his now famous Civil War stories within the pages of the Examiner.

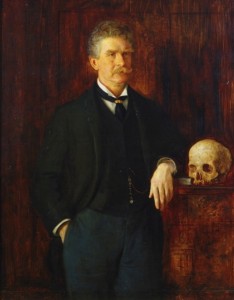

Similar to the first half of the 1870s, Bierce thrived as a writer during the late-1880s and early-1890s even while his personal life seemed to be falling to pieces around him. In 1888, Bierce separated from his wife, Mollie, after seventeen years of marriage when he found revealing letters written to her from a European admirer. To make matters worse for Bierce, in 1889, his seventeen-year-old son, Day, became involved in a love triangle that resulted in him shooting and killing his rival before turning the gun on himself. Nonetheless, Bierce persevered and wrote and published during this period Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (1891), The Monk and the Hangman’s Daughter (1892), Black Beetles in Amber (1892), and Can Such Things Be? (1893).

Between 1894 and 1908 Bierce spent much of his time writing for William Randolph Hearst’s various newspaper publications (and developing a love-hate relationship with the man) and traveling between California and Washington, D.C. During this period he also saw a published revision and expansion of Tales as Soldiers and Civilians as In the Midst of Life: Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (1896), as well as the publication of Fantastic Fables (1899), Shapes of Clay (1903), and The Devil’s Dictionary (1906). However, Bierce would again experience personal hardship and loss shortly after the turn of the century. In 1901, his second son, Leigh, died at the age of twenty-seven from pneumonia as a result of alcohol abuse. In the fall of the same year, his daughter, Helen, came down with typhoid fever and spent eight weeks of uncertainty in a hospital before recovering her health. And, while Bierce had been separated from his wife for seventeen years before she filed for divorce in December of 1904, he nonetheless mourned her death in April of 1905.

From 1908 until his venture into the unknown in Mexico in 1914, Bierce’s writing output waned and he became more of a recluse in his personal life. Nevertheless, he saw the publication of The Shadow on the Dial and Other Essays (1909) and a twelve-volume edition of his works titled Collected Works (1912). He also penned a writing “how-to” titled Write It Right (1909). In 1908, he bitterly broke with Hearst and his newspaper publications and returned a few more times to California before formulating plans from Washington, D.C. in October of 1913 “of going through Mexico on horseback—an ‘innocent by-stander’ in the [Mexican Revolutionary] war.”

From 1908 until his venture into the unknown in Mexico in 1914, Bierce’s writing output waned and he became more of a recluse in his personal life. Nevertheless, he saw the publication of The Shadow on the Dial and Other Essays (1909) and a twelve-volume edition of his works titled Collected Works (1912). He also penned a writing “how-to” titled Write It Right (1909). In 1908, he bitterly broke with Hearst and his newspaper publications and returned a few more times to California before formulating plans from Washington, D.C. in October of 1913 “of going through Mexico on horseback—an ‘innocent by-stander’ in the [Mexican Revolutionary] war.”

Much has been debated over the last century about the eventual fate of Ambrose Bierce. What is known is that Bierce, at the age of 71, traveled across the country by rail to Texas, with stops along the way to visit Missionary Ridge, Chickamauga, and other American Civil War battlegrounds, as well as New Orleans where he was interviewed by a reporter for the States in which he is quoted as saying, “I’m on my way to Mexico because I like the game,” before finally crossing the Mexican border between El Paso and Ciudad Juarez on horseback. However, after crossing into Mexico, he disappeared without a trace. Today, his disappearance remains a great mystery and one of the most famous in literary history.