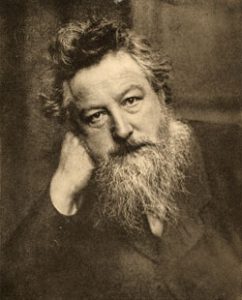

William Morris was a designer of stained glass, tapestries, wallpaper, chintzes, furniture, books, and typefaces. He was also a preservationist, socialist, poet, novelist, lecturer, calligrapher, translator of classic Icelandic and early English sagas, and founder of the Kelmscott Press. Born in 1834, he died in 1896 at age 62 due to (according to his physician): “simply being William Morris, and having done more work than most ten men.” Morris became involved with socialist causes in the late 1870s and found it impossible to separate aesthetic issues from social and political ones. In his view, social reform was simply an extension of his arts and crafts production.

William Morris was a designer of stained glass, tapestries, wallpaper, chintzes, furniture, books, and typefaces. He was also a preservationist, socialist, poet, novelist, lecturer, calligrapher, translator of classic Icelandic and early English sagas, and founder of the Kelmscott Press. Born in 1834, he died in 1896 at age 62 due to (according to his physician): “simply being William Morris, and having done more work than most ten men.” Morris became involved with socialist causes in the late 1870s and found it impossible to separate aesthetic issues from social and political ones. In his view, social reform was simply an extension of his arts and crafts production.

Morris’s obituary in The New York Times stressed the variety of his life and work, the “unusual combination of manufacture and literature that he seemed to have a sort of dual existence in the eyes of the public. His poems were ‘by Morris, the wallpaper maker,’ his wallpapers, ‘by Morris, the poet’.”

While the aesthetic success of Morris’ work, especially his book design, has been widely debated, the ideals, passion, and commitment which drove his work are hard to dispute. The obituary writer for The Times describes him as “a singularly sincere artist, who worked hard to make the world a little more beautiful and a little more honest.” Morris was an incredibly detailed and thorough designer and craftsman, but he was motivated not by the end product itself, but rather by the values they represented. In Master Makers of the Book, William Orcutt states: “Morris developed no particular interest in designing English mansions or public buildings, stately though they might be. What he really wanted to do was to reform English taste, and to force people to furnish and decorate their homes with things that were beautiful instead of ugly.”