Longview Asylum: Good Intentions Gone Wrong

By: Gabriel Brown

Longview Asylum has a long, storied history. On April 7th, 1856, the state legislature of Ohio passed an act which divided the state into three districts (Northern, Central, and Southern) for the purposes of treating the mentally ill (Genealogy Trails 2017). In less than a year, however, the legislature passed an act making Hamilton County its own district for the purposes of lunatic asylums, resulting in the building of Longview with the support of state funds. Built along the Miami & Erie Canal in what was considered part of Carthage, Longview Asylum had a capacity of 400 patients (Prout 2017). Thirty years later, it held 800 patients, was grossly underfunded, and contended with the open sewer the canal had become. Expansions continued throughout the 1900s, eventually raising capacity above 1000; even so, there were over 3000 patients at a time.

While the history of the asylum itself is fascinating, a tale echoed by asylums and state hospitals around the nation, it is the history of its patients that is truly fascinating. The state of mental health care in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is a sordid tale, and one that would become the source of fears and nightmares. The Irish are known for their short tempers and rampant alcoholism, aspects which are only partially correct when applied to the whole of Irish people or Irish people in America. This stereotype of their behavior contributes to their reasons for entering Longview. An analysis of Cincinnati death records reveals insights into how patients were treated at Longview, and an analysis of the patients of Irish birth adds an additional layer of intrigue.

Supplied with the search terms “Longview” and “Ireland,” the database of Cincinnati death records provides 122 results. Of these results, 78 were women (average age 59.8 years) and 44 men (average age 56.4 years). The average age of the entire sample was 58.6 years. From this sample, 74 patients are listed as having died from insanity (60.7%), but only two of them are listed as having died from insanity alone. Diagnoses appearing alongside insanity were acute dysentery (5.4% of the subset), dysentery (5.4%), Bright’s disease (1.4%), cellulitis (1.4%), cerebral congestion (6.8%), cirrhosis (1.4%), general paralysis (8.1%), heart disease (10.8%), pneumonia (1.4%), manical exhaustion (2.7%), marasmus (36.5%), nephritis (2.7%), peritonitis (2.7%), phthisis pulmonalis (4%), pneumonia (4%), pulmonary hemorrhage (1.4%), ramolissement (2.7%), and senile exhaustion (1.4%). This means that, of this subset of 74 patients, approximately 28.4% died of causes relating to infection. In particular, dysentery can be linked to the conditions of the canal. All can be linked to the overcrowding of the asylum. All can be linked to horribly unsanitary conditions and probably mistreatment.

Mistreatment may seem to be a bit of a stretch, but reviewing the list of causes of death illuminates the most common cause of death cited. Returning to the full sample of 122 patients, 29.5% have marasmus listed as a cause of death, either with insanity, in conjunction with another cause, or alone. Marasmus is a condition not often referenced in modern medical practice in the United States. It is a form of severe malnutrition, with symptoms including chronic diarrhea, vulnerability to respiratory infections, intellectual disability, dry skin, brittle hair, avolition, absence of energy, loss of muscle mass, and loss of subcutaneous fat (Healthline Media 2017). Today, marasmus is only found in developing countries that face severe food shortages and sanitation problems.

Finding marasmus to be the most commonly recorded cause of death among Irish patients of Longview tells us that these patients were being mistreated. Because marasmus is treatable, and may have been masked by other conditions, it is likely that many more patients suffered such mistreatment but survived long enough to be released prior to their deaths. This is not to say, of course, that other patients were not being mistreated, but 29.5% of a given population dying of the same cause is cause for concern.

Imagine for a moment what is must have felt like. Cold, dark, smelling of too many unwashed bodies being crammed into the same space for too long, and an unrelenting odor of feces must have been part of their lives. The food was poor, when it was provided, because there simply wasn’t money to buy enough to feed every patient regularly. If you are suffering from any of the many modern mental illnesses that fell into the umbrella term of “insanity,” then the likelihood that the condition is worsened by your circumstances is fairly high.

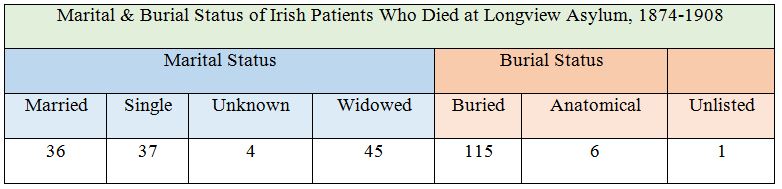

The sense of isolation invoked by such an environment might be exacerbated by a lack of familial contact. The majority of Irish patients in Longview were unmarried (see table below), and many were buried in the cemetery on the asylum grounds (St. Joseph’s New was a close second, but more commonly with married and widowed patients). These factors compounded each other, and spread fear throughout the community that prevented other patients from seeking services. It also contributed to the stereotype of mentally ill patients, which likely resulted in more individuals being taken to the asylum without need, further straining already thin resources.

The story of the Irish patients in Longview is not totally unique, but it provides a focus for teasing out information. Analyzing the reported causes of death hints at the poor state of accommodation and treatment for patients. These conditions perpetuated fears and stereotypes that lead to further taxing of an already burdened system. Thankfully, many of the practices that existed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have been replaced by more proven therapies, and it is no longer the norm to starve, beat, and torment patients in an effort to bring them back to sanity and “normality.” What this analysis reminds us of, however, is that we must never forget this part of our history, especially when so many of us can claim Irish heritage and know of the other social struggles faced by the Irish in America and across the globe.

Bibliography

“Cincinnati Birth and Death Records, 1865-1912.” 2017. University of Cincinnati Digital Resource Commons. University of Cincinnati Historical Records. http://digital.libraries.uc.edu/collections/birthdeath/

Genealogy Trails. 2017. “State Facilities.” Visited 28 March 2017. http://genealogytrails.com/ohio/ohioinsaneasylums.htm

Healthline Media. 2017. “What You Should Know About Marasmus.” Visited 30 March 2017. http://www.healthline.com/health/marasmus#overview1

Prout, Don. 2017. “Cincinnati Views: Hospitals 3.” Visited 30 March 2017. http://www.cincinnativiews.net/hospitals_part_3.htm