Irish Domestics in Cincinnati

By: Samantha Besse

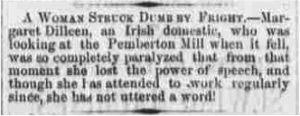

Cincinnati Daily Press – A Woman Struck Dumb by Fright

On October 16, 1861, the Cincinnati Daily Press ran a short notice of an Irish domestic named Margaret Dilleen, who witnessed the Pemberton Mill fall and experienced so much fear that she became mute. Despite this, “she has attended to work regularly since, [though] she has not uttered a word!” (Cincinnati Daily Press 1861). This is a wonderful example of the hard-headedness and determination that was characteristic of so many Irish domestics. Despite some harsh criticisms about the stereotype of the Irish “Bridget”, Irish domestics played a very dominant role in the domestic service industry, specifically in Cincinnati between the 1800s and 1900s. Based on statistical data collected from death records, case studies of specific areas of Cincinnati, and stories from Irish domestics across America, it is clear that the Irish domestic was an integral part in helping run a functioning American household.

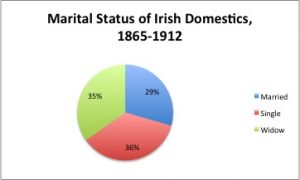

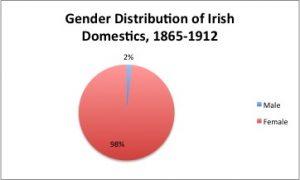

Using death records from 1865 to 1912 to investigate the life of Irish domestics in Cincinnati, data was compiled and analyzed for 514 maids and housekeepers who were born in Ireland. Of the total sample, ninety eight percent were female, while only two percent of Irish domestics were male. This strong favoring of women over men for domestic roles is not surprising, as domestic work was generally seen as “feminine”. However, unlike the gender distribution, the marital status of Irish domestics was more evenly spread, with twenty nine percent married, thirty five percent widows, and thirty six percent single.

This data supports the observation by Maureen O’Rourke Murphy that “The immigration of single women distinguishes nineteenth-century Irish immigration to North America from the pattern of other western European migration. More women than men emigrated, and they did so as single women,” (O’Rourke Murphy). The influx of single Irish women to America was fueled by the devastation of the Famine, including the financial implications. With fewer job opportunities for men and women in Ireland, marriage was delayed because of the lack of financial stability that many young people faced. Additionally, “Scarce land meant that only one daughter received a dowry, without which young women’s prospects for marriage were slim,” (Muccino 2011). With a negative outlook on marriage and work, single Irish women decided to take their chances in America.

However, once arriving in America, the opportunities for Irish women were very narrow, and most turned to housework. Margaret Lynch-Brennan noted that when she asked multiple Irish domestics why so many women took on these roles, their answers were the same – they weren’t fit to do anything else. The opinion of the Catholic Church also influenced the employment of many single Irish women. Needing to work to provide for themselves, single women took on roles that were “feminine,” heading the gender stereotypes that religion and society placed upon them. The availability of domestic jobs increased “as the status of domestic service declined from skilled helper to hired drudge, [and] American-born girls fled to the factories or to sewing at home. Irish girls replaced them as domestics, and the “Bridget” stereotype was institutionalized,” (Muccino 2011). The Irish “Bridget” was often described as ignorant and awkward as to American culture and expectations. Embracing the assertive attitude of women in Ireland, Irish domestics were often seen as “insolent, defiant, [having] a temper,” and “unaware of the distinction in class between mistress and maid,” (Lynch-Brennan, 71-72). For these reasons, “No Irish Need Apply” was included at the end of many advertisements looking for domestic servants.

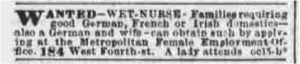

Cincinnati Daily Press Ad for Irish Domestic

However, there were still plenty of ads specifically looking for Irish domestics, and “by 1845, about two thirds of the nation’s servants were Irish immigrants,” (Muccino 2011). The hard work and determination of Irish women kept them employed, and made them so desirable that one young

Letter to Santa 1908

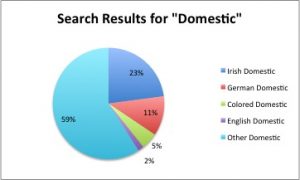

girl living in Avondale, Ohio in 1906 asked for an Irish maid in her letter to Santa Claus. Search results for “domestic” in the Cincinnati death record database yielded the highest percentage for “Irish domestic” over any other group, except for domestics with no ethnicity listed. Despite the often demanding role of being a “maid-of-all-work,” there were many benefits that attracted Irish immigrants to this line of work (Lynch-Brennan, 101). Single women were hired as live-in maids, which provided them with free room and board. This factored greatly into the financial benefits of the job, and wages for experienced workers “were higher than salaries paid to teachers, office workers, and shop and factory workers. Thus, domestic servants could save their wages; Salmon calculated that the average domestic servant could save around $150 each year,” (Lynch-Brennan). This money was deposited in banks or sent back to Ireland to help family and others who were in need due to the Famine.

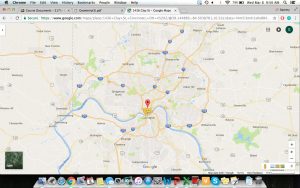

From the collection of 514 Irish domestics who died in Cincinnati between 1865 and 1912, thirty individuals were selected for further analysis. Selection of individuals was based on an equal representation of domestics of all marital status, reaching across all year ranges. Aside from these criteria, selection of individuals was random. The map included shows the distribution of housing for the thirty individuals. Aside from a few outliers, the vast majority of Irish domestics resided in downtown Cincinnati, directly across the river from Covington, Kentucky. This area is very close to Cincinnati’s Third Ward, which covered the area encompassed by the Public Landing on the west, the incorporation line on the east, the Ohio River on the south, and Third Street on the north. While the area was very diverse and included a mix of people of many different ethnicities, the presence of Irish women in domestic jobs was very strong. According to research by Eileen Muccino, 94 Irish women in the Third Ward worked as servants, which surpasses all other ethnicities. Out of thirty-four women who worked as part of the live-in staff at the Spencer House, a hotel that opened in Cincinnati in 1853, twenty-eight were born in Ireland. One of these women was a cook, while the remaining twenty-seven were domestics.

Map of Homes for 30 Irish Domestics

Although Irish immigrant women were often subjected to stereotypes, Irish immigrants in Cincinnati did their best to overcome these assumptions. While a large number of Irish women were domestics, they often gave up their job to get married and focus on their family. For the children of those born in Ireland, education was heavily emphasized and fewer women entered the domestic work force. This encouragement to opt out of the job of a domestic servant was most likely influenced by the difficult work, the lack of respect, and the vastly greater opportunities provided. Overall, the life of an Irish domestic in Cincinnati, while often challenging, was very beneficial for many Irish women and families in the 1800s and 1900s. Although the work of a “Bridget” was tough, the Irish immigrant was tougher.

Bibliography

“Cincinnati Birth and Death Records, 1865-1912.” 2017. University of Cincinnati Digital Resource Commons. University of Cincinnati Historical Records. http://digital.libraries.uc.edu/collections/birthdeath/

Cincinnati Daily Press 22 March 1860: 1.

Cincinnati Daily Press 16 October 1861: 3.

Lynch-Brennan. The Irish Bridget: Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840-1930. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2009.

Muccino, Eileen. “Successful Bridgets: Irish Women in Cincinnati’s Third Ward in 1860.” The Tracer March 2012: 1, 18-22, 11.

—. “Successful Bridgets: Irish Women in Cincinnati’s Third Ward in 1860.” The Tracer November 2011: 97, 112-116.

O’Rourke Murhpy, Maureen. “Foreward.” Lynch-Brennan, Margaret. The Irish Bridget: Irish Immigrant Women in Domestic Service in America, 1840-1930. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2009.