St. Joseph’s New Cemetery: A Prominent Resting Place for Cincinnati’s Irish

By: Colleen O’Brien

New St. Joseph Cemetery Plaque

During the 1849-1854 cholera epidemic, St. Joseph Cemetery, also known as Old St. Joseph Cemetery, reached its capacity, especially within the Irish allotment. The deceased were stacked upon one another and buried in mass graves. To relieve this crowding, in 1853 Archbishop John Baptist Purcell of the Cincinnati Archdiocese purchased roughly 61 acres of farmland two miles west of Old St. Joseph and established St. Joseph’s New Cemetery, which is more commonly known as New St. Joseph Cemetery (Grace and White 2004). The digitized Cincinnati birth and death records, The Cincinnati Enquirer, and grave markers can be used to provide a more complete narrative of Irish immigrants buried in St. Joseph’s New Cemetery.

Of the 25,348 individuals laid to rest at St. Joseph’s New Cemetery from 1865 to 1912, 11,526 (45%) are from the city of Cincinnati, 8,540 (34%) are Irish, 455 (2%) are Germans, 267 (1%) are English, and 215 (1%) are Italian. The remaining 4,345 (17%) individuals’ origins could not be determined or were not listed. The focus of this analysis will be on the interesting cases of the 8,540 Irish who make up the second largest population within the cemetery.

Grave of Michael P. Reynolds

Phthisis Pulmonalis, or tuberculosis, and cholera were some of the leading causes of death during the 1800s due to unsanitary conditions and close proximity of the diseased to the healthy. Eight hundred and eight (1%) of the 8,540 Irish buried in New St. Joseph Cemetery died from tuberculosis, such as Michael P. Reynolds. He was a married carpenter who lived on 108 Gest Street and died of tuberculosis on March 28, 1877 at the age of 36, according to his death record. Yet his marker shows he died on March 27 and was from Cloone, spelled Cloon on the marker, parish in

Grave of John T. Enright

County Leitrim, Ireland. The discrepancy between dates and spelling is likely a clerical error. Fifty (.6%) of the 8,540 Irish perished from cholera. It is important to note these individuals, who are buried in St. Joseph’s New, are not from the 1849-1854 or 1866 epidemics [1]. Rather, the deaths range from 1885 to 1893 and the earliest Irish death recorded is that of Julia Corcoran who died on August 8, 1885 at the age of 60 at her home on 12 Linnaeus Street Not all deaths were by contracted diseases. One Irishman, John T. Enright, a native of County Limerick, for example, died of necrosis [2] on the mastoid portion of his temporal bone on September 7, 1892. He was a contractor between 62-63 years of age. Enright’s death record lists the age of 62, while his burial marker lists the age of 63. He lived at the corner of High and Evans Streets with his wife Ann.

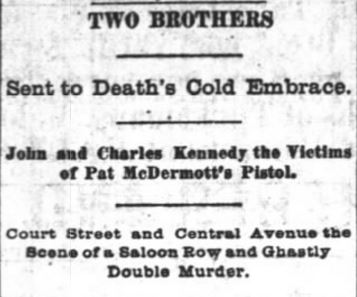

McCann Brothers’ Death Notice

Unsanitary and poor living conditions were not the only things to be concerned about while living in the city. Twenty-five (.3%) of the 8,540 Irish buried in New St. Joseph Cemetery died by homicide, as “Violent crimes were part of the burgeoning urban life in early Cincinnati” (Grace and White 2004). For example, two brothers, John and Charles Kennedy, were both shot and killed on June 10, 1884 by Pat McDermott after attending a meeting at Bricklayer’s Hall on Central Avenue. The three men gathered at Hart’s Saloon to drink. At about midnight, “the men got into a heated discussion over some trivial matter” and began brawling (Cincinnati Enquirer 1884). A police officer, accompanied by an Enquirer reporter, broke up the fight and ordered saloon keeper John Hart to close for the night. McDermott stormed out of the saloon shouting, “I’ll get even with you fellows,” and the madness appeared to be over for the moment (Cincinnati Enquirer 1884). Unbeknownst to the Kennedy brothers and the other saloon patrons, McDermott left to fetch his revolver. Not more than thirty minutes later, the sound of three gunshots rang through the air. The Kennedy brothers were still alive when the officers found them about three minutes later, however they expired on the way to the hospital. A Cincinnati Enquirer article from Saturday, June 14, 1884 states, “It developed at the inquest that the right names of the deceased were McCann, but that they were generally known by the name of Kennedy,” which explains why the death records did not originally align with what was printed (Cincinnati Enquirer 1884). The Cincinnati birth and death records create a more complete story, such as Charles’ given name was actually Robert. John died at the age of 43 and left his wife a widow. Robert, aged 33, was single. Interestingly, the gunshot wounds of both brothers pierced the heart and John’s also went through the lungs while Robert’s hit his liver. Both the McCann brothers were laid to rest in St. Joseph’s New Cemetery under the direction of the Habig Funeral Home. The exact plot locations and grave markers of John and Robert have been lost, but the two are buried in section three of the cemetery. Incidents such as the homicide of the McCann brothers are important to examine because they tend to illustrate the anti-Irish stereotypes, such as the Irish being violent and alcoholic, along with a trope like the “No Irish Need Apply” nativist stance which widely occurred in America and within the city of Cincinnati.

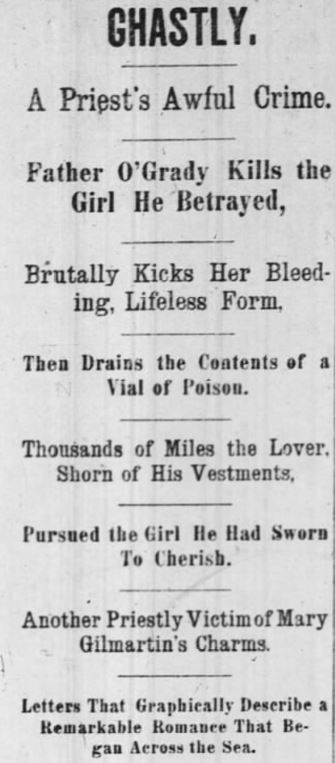

Mary Gilmartin Headlines

Almost a decade later, on April 25, 1894, a nineteen year old female suffered a similar fate as the McCann brothers. As the story was told, Father Dominick O’Grady and Mary “Molly” Gilmartin’s affair began across the sea in Tobercurry, County Sligo, Ireland. On her deathbed, Mary’s mother asked the young priest to be a guardian to her daughter. The pair saw each other nearly every day and eventually Father O’Grady proposed marriage, but was continually reminded by Mary that he was a priest. The infatuation soon ended, as O’Grady quickly began controlling Mary’s life by telling her to go in a convent and even took the $1,000 given to Mary by her father so she could attend school in Dublin (Cincinnati Enquirer 1894). He left her a few hundred dollars and bought her a ticket on the ship Teutonic, which was sailing to America. Mary wrote a letter begging for Father O’Grady to come to America to set things right. He obliged and the couple eloped in Buffalo, New York. The pair made their way to Chicago to visit Gilmartin’s brother, Michael, who recently became a priest. Word got back to Ireland that Father O’Grady and Mary eloped and the other priests in Father Michael’s parish advised Mary to return to Tobercurry. Father O’Grady returned instead out of fear of damaging Mary’s reputation. She eventually arrived in Cincinnati and stayed at the home of Mrs. Charles Tibbles. However, Father O’Grady soon arrived because Mary feared she might be pregnant and did not know what to do. On the night of her death at six o’clock, Mary left the Tibbles residence and took the Avondale streetcar to meet with O’Grady (Cincinnati Enquirer 1894). Supposedly the couple discussed their future, both frequently mentioned death. This conversation seemed to be the last straw for the young priest because he turned Mary around and shot her in the head. While in custody by the police O’Grady attempted suicide by arsenic, but escaped death until his trial. A Dr. Querner examined Mary’s body and a funeral was arranged by Sullivan & Co.

Mary Gilmartin Headline

Funeral Home. Her final resting place is in section two of New St. Joseph Cemetery. However, this is only one version of the Gilmartin tale. Another version has it that her family sent her to Chicago to get away from the undue influence of the priest and to be in the care of her brother. When she later came to Cincinnati, she was living with cousins when the priest, who had trailed her to America, accosted her on the street as she was going to work one morning and shot her. Her tragic death was followed by a funeral in which, again according to one story, hundreds of local Irish accompanied the body to Price Hill and New St. Joseph’s Cemetery. The priest was adjudged insane, and the Catholic Church stripped him of his Holy Orders. However, after a period of incarceration in an asylum, he was released, moved to Philadelphia, and was re-took his vows. Molly Gilmartin’s grave was never marked until decades later when the Gilmartin relatives in Sligo attempted to piece together this part of their family history. Through the efforts of the Cincinnati Police Department and the Cincinnati Museum Center Library and Archives, the full tale was revealed and the family had closure.

Mary Gilmartin

Oftentimes, the story of an individual can be forgotten. This analysis attempts to shed light upon those, particularly Irish, individuals who so often become just names on painstakingly carved slabs of marble. It is important to remember the Irish made up the second largest immigrant population in Cincinnati after the Germans. Overall, the Cincinnati working-class Irish confronted a difficult life in the city. Not only did they face unsanitary conditions, which led to contracting tuberculosis and cholera, the Irish and other city-dwellers were also faced with the impending risk of being on the receiving end of violent crimes as Cincinnati grew. Despite these hardships, the Irish have left important marks within the city, especially its cemeteries. Graves often list the home county and parish in Ireland, which illustrates a sense of pride for their roots—a theme that is common amongst many Irish and Irish-Americans today.

Entrance of New St. Joseph’s Cemetery

Bibliography

“Cincinnati Birth and Death Records, 1865-1912.” 2017. University of Cincinnati Digital Resource Commons. University of Cincinnati Historical Records. http://digital.libraries.uc.edu/collections/birthdeath/

Grace, Kevin, and Tom White. Cincinnati Cemeteries: The Queen City Underground. Charleston SC, Arcadia Publishing, 2004.

“Cincinnati Enquirer- Historical Newspapers, 1841-2017.” Cincinnati Enquirer, Newspapers.com, 2017. http://cincinnati.newspapers.com/?xid=527

[1] More information on the cholera epidemics of 1849-1854 and 1866 can be found on Megan Dunlevy’s post, “Cholera and the Queen City.”

[2] Necrosis- a cellular injury in which all or most of the cells in an organ or tissue die due to disease, injury, or failure of blood supply.