Stillbirths and Maternal Mortality

By: Jayci Kuhn

Stillbirths and maternal deaths have affected the entire world for as long as history has been recorded. Looking at the countries with the highest prevalence in stillbirths and maternal deaths in the 1800s and 1900s, one can see that they were considered “high poverty.” Between 1845 and 1852, the Potato Famine contributed greatly to the poverty levels in Ireland, causing nearly one million Irish to immigrate to the United States, making up half of all immigrants in America.

Cincinnati, Ohio was one of the eventual destinations for Irish immigrants hoping to feed and care for their families. The Ohio River offered immigrants opportunities to work on the waterfront, as did the construction of the Miami and Erie Canal. The Irish were sometimes discriminated against and desperate for work, meaning they were forced to take dangerous and unskilled jobs with low pay like coal mining, and as common laborers and construction workers on the railroad.

In the Cincinnati birth and death records, there were three recorded stillbirths from 1882 to 1902. A trend in the stillbirths shows that all the fathers were of Irish descent, one a laborer and the other an express man. All three families lived in working class or low-income neighborhoods, so most likely they were living in poverty. Considering as a corollary to the Irish who did not emigrate, one can consider the work of Richard Steckel of The Ohio State University, who collected data on the percent of babies stillborn in Dublin, Ireland from 1865-1925. Examining the statistics, there is a clear increase in Irish stillbirths over time, especially 1870-1900 when most mothers born into poverty were giving birth themselves without the aid of hospital personnel.

And living in poverty in Cincinnati most likely meant both husband and wife working physically arduous jobs, a majority of income being spent on food, lack of medical attention and advice, and personal hygiene and health practices being meager. Accommodations for the Irish in America were not always favorable. They often lived in over-populated, lower class homes that were usually in urban areas. Living in a city introduced all kinds of health hazards, from pollution to infectious diseases to unsafe drinking water. Maternal health was a large issue under these living conditions, and there was little prenatal care other than fasting diets and blood- letting. This was intended to ensure a small baby and easy birth. But disastrously, this left pregnant women weak when going into labor. A long labor would cause further exhaustion, and leave women with little ability to recover if they experienced complications, infection, or blood loss. During this time, women could expect an average of seven children. Bearing this many children over time, in addition to questionable nutrition and medical care, took its toll on the health of both women and babies.

The Cincinnati death records show there were eleven maternal deaths during childbirth from 1866 to 1900. The mothers’ ages ranged from 23-36 years old, and all of these women lived in working class neighborhoods. Seven of eleven deaths took place in a hospital and any additional illnesses or complications were not documented for these women. Most likely they were unable to live through the demands of labor due to poor healthcare before and during childbirth.

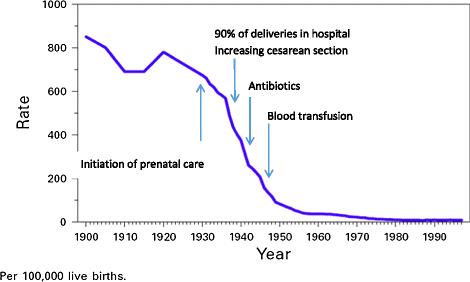

Fortunately, developments in preventative medicine and extensive research over the past century have increased awareness of the importance of maternal health on both the mother and child. The rate of stillbirths and maternal deaths in the United States has dropped tremendously with this knowledge and healthcare for lower class families. There are numerous programs and clinics spread around the Cincinnati area that provide prenatal care and assistance in mental, physical or emotional help to low-income mothers and families.

Interventions associated with historical reduction in maternal mortality, United States, 1900–2000. Adapted from Johnson 2001 [23].

Bibliography:

“Birth weights and stillbirths in historical perspective.” Birth weights and stillbirths in historical perspective. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Mar. 2017.

http://archive.unu.edu/unupress/food2/UID03E/UID03E09.HTM

Cincinnati Birth and Death Records, 1865-1912. University of Cincinnati Digital Resource Commons, http://digital.libraries.uc.edu/collections/birthdeath/.

“Child Mortality.” Our World In Data. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Mar. 2017

https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality/

“Facts about Stillbirth.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 07 Mar. 2017. Web. 29 Mar. 2017.

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/stillbirth/facts.html

Goldenberg, Robert L., and Elizabeth M. McClure. “Maternal, fetal and neonatal mortality: lessons learned from historical changes in high income countries and their potential application to low-income countries.” Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology. BioMed Central, 22 Jan. 2015. Web. 29 Mar. 2017.

https://mhnpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40748-014-0004-z

“Irish 1840’s – 1910.” Cincinnati: A City of Immigrants. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Mar. 2017.

http://www.cincinnati-cityofimmigrants.com/irish/

“Why So Many Women Used To Die During Childbirth.” BellyBelly. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Mar. 2017.

https://www.bellybelly.com.au/birth/why-women-used-to-die-during-childbirth/

Writer, Leaf Group. “Pregnancy in the 1800s.” Synonym. Synonym, 18 Oct. 2013. Web. 29 Mar. 2017.

http://classroom.synonym.com/pregnancy-1800s-9138.html