Tuberculosis and the Cincinnati Irish

By: Jessica Heskett

Throughout history, sanitation along with medicinal technology was insufficiently researched or developed to fight off infection relative to current practices. In the beginning of the 20th century, infectious respiratory diseases comprised almost 25% of all deaths in America (Guyer, et al). Tuberculosis was one of those diseases. The causative organism, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, was discovered in 1882 but unfortunately merely identifying the disease did little to help with epidemics as effective treatments were not discovered until the early 1900s (Murray, John F., Dean E. Schraufnagel, and Philip C. Hopewell). Characterized by symptoms of coughing up blood or sputum, weakness, weight loss, chills, fever, and night sweats, tuberculosis killed so many people because as the disease progresses, the bacteria eat away at the individual’s lung tissue, which has serious sequela.

Sign Warning People of Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis reached its highest peak in the general population in the 1700s, with almost 900 people dying out of every 100,000 people infected (Mandal, Ananya). The disease became increasingly prevalent due to its mode of transmission; sneezing, coughing, or even talking spread tiny droplets through the air that would stay suspended for long periods of time, causing the disease to be highly contagious. Fortunately, as living conditions improved over time, the incidence of tuberculosis decreased. On the other hand, those who were disadvantaged, particularly the poor and immigrants who lived in crowded and squalid conditions, continued to suffer from this disease due to its communicability (Figueroa-Munoz, Jose I., and Pilar Ramon-Pardo).

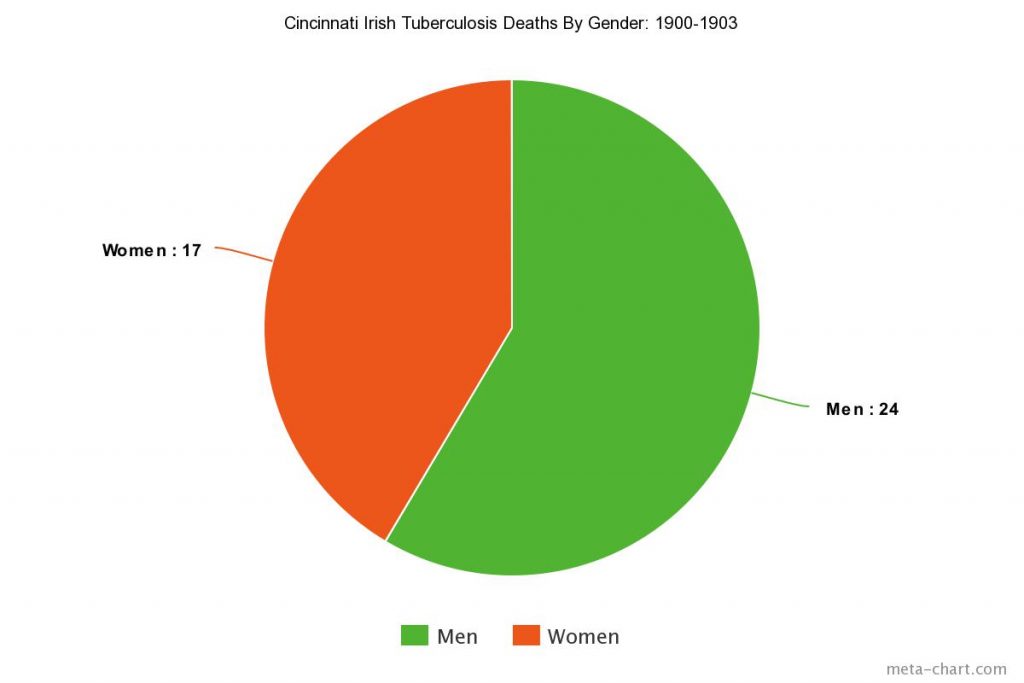

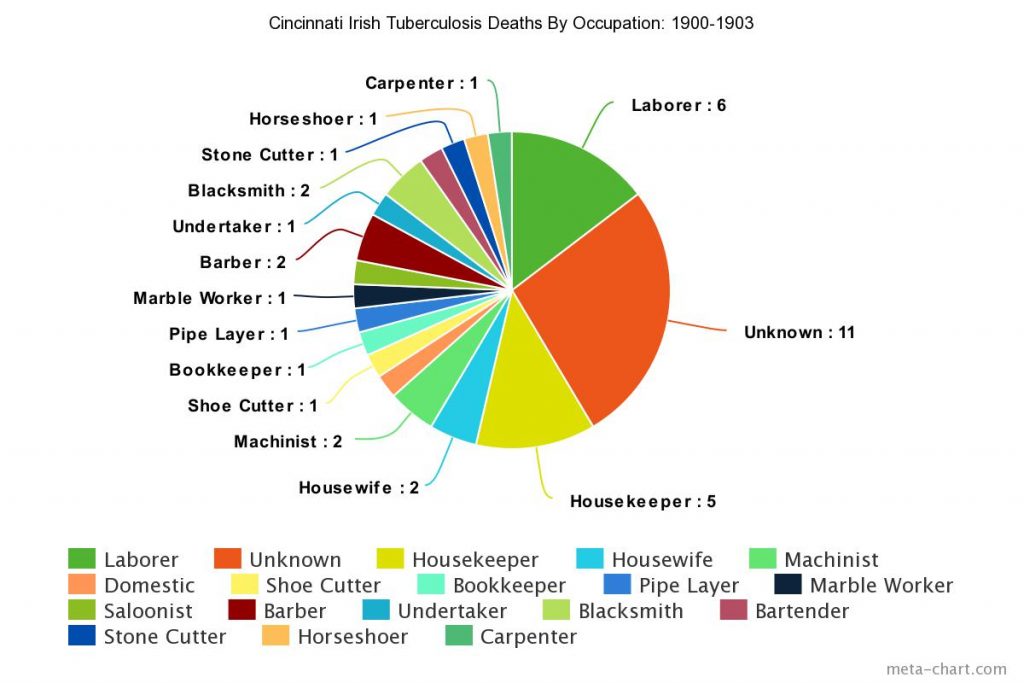

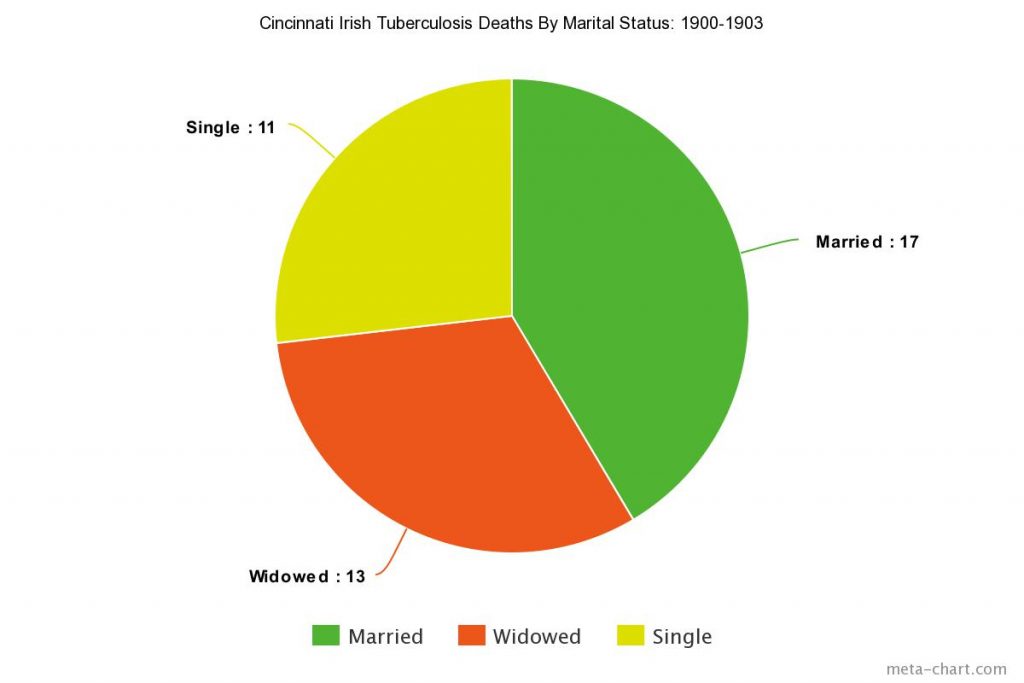

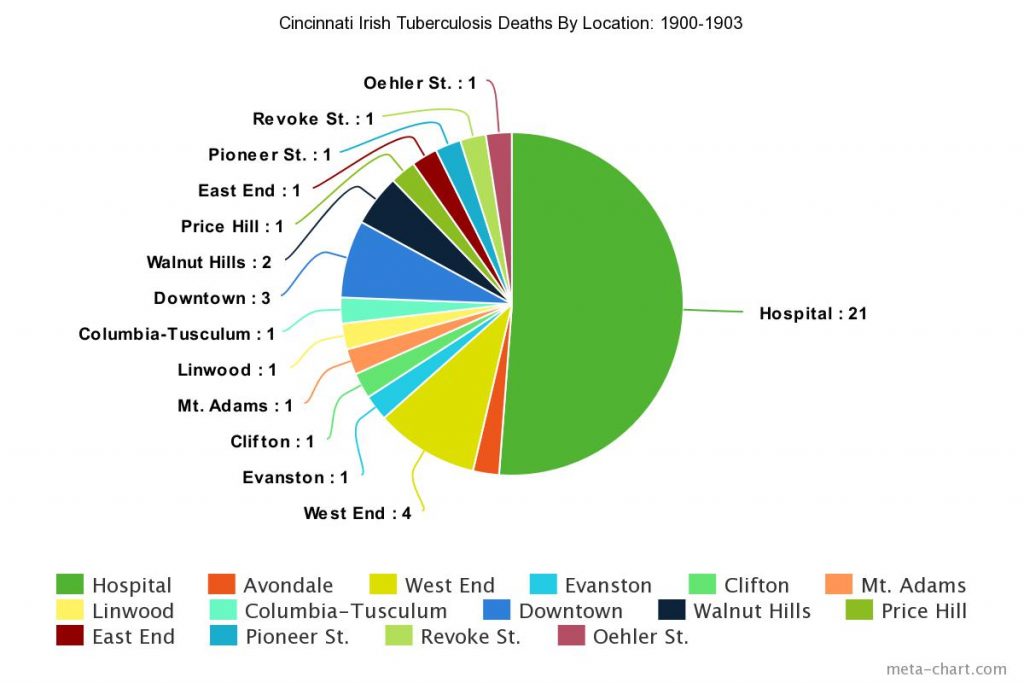

Exploratory research was conducted to compare the incidence of tuberculosis in the general population and the incidence of tuberculosis among Irish emigrants. Utilizing the digitized Cincinnati birth and death records of 1865-1912, a search of Irish emigrants who died of tuberculosis was conducted. After searching the 528,000 records in the collection, 268 results appeared regarding Irish-American residents who died of tuberculosis. For this research study, 41 death records were utilized from the years 1900-1903. These records were analyzed because this was the time when the incidence of tuberculosis was highest amongst the Irish and statistics were calculated for Irish deaths caused by tuberculosis during the designated time period. Of the 1,567 Irish deaths overall, 41 of them died from tuberculosis (2.68%). Of the 1,253 individuals who died of tuberculosis in Cincinnati, 41 of them were Irish (3.35%). According to these records, 24 were male (58.5%) and 17 were female (41.5%). Location of death was also analyzed to determine the trends amongst incidences. Hospitals alone contained 21 deaths (51.2%). Of the neighborhoods affected, the West End had four deaths (9.8%), the city basin had three deaths (7.3%), Walnut Hills had two deaths (4.9%), and Oehler Street, Revoke Street, Pioneer Street, the East End, Price Hill, Columbia-Tusculum, Linwood, Mount Adams, Clifton, Evanston, and Avondale all accumulated one death each (2.4% each). Of those infected with tuberculosis, 17 were married (41.5%), 13 were widowed (31.7%), and 11 were single (26.8%). Finally, occupations of the deceased were analyzed for trends. Of the occupations analyzed, 11 were jobless (26.8%), six were laborers (14.6%), five were housekeepers (12.2%), and housewives, machinists, barbers, and blacksmiths had two each (4.9% each). Carpenters, horseshoers, stone cutters, undertakers, bartenders, saloonists, marble workers, pipe layers, bookkeepers, shoe cutters, and domestics had one each (2.4% each).

Tuberculosis Deaths by Gender

Tuberculosis Deaths by Occupation

Tuberculosis Deaths by Marital Status

Tuberculosis Deaths by Location

Due to its extensive history and transparent trends, tuberculosis is sometimes referred to as the disease of the poor. Since the stereotypical living conditions of the poor incorporated poor ventilation in highly crowded and unsanitary tenements, communicable diseases were often a problem (Buckley, Dan). Although the Irish emigrated as a way to escape famine and despair, they often were not met with success. Upon arriving in the United States, the Irish had difficulty finding jobs and were forced back into the poor living conditions they so desperately tried to escape. This appears to be the case for the working-class Irish in Cincinnati. After analyzing the occupations of those that died, it was found that the Irish emigrants who were able to obtain a job tended to possess lower-class jobs. Analysis also revealed that these individuals tended to die in lower income neighborhoods and hospitals. In these impoverished parts of Cincinnati, disease festered, most likely due to “overcrowding, poorly ventilated housing, malnutrition, smoking, stress, social deprivation and poor social capital” (Figueroa-Munoz, Jose I., and Pilar Ramon-Pardo).

Cartoon Warning Against the Spread of Tuberculosis

Many might consider dying in a hospital the best alternative. This environment usually stipulates the individual being able to receive the most comprehensive treatment leading up to his or her death. Nevertheless, hospitals could not always provide the best treatment for individuals with tuberculosis. Wealthy people, on the other hand, were able to receive treatment at sanatoriums: the gold standard of the time. Sanatoriums were developed to help treat and cure tuberculosis. These establishments provided a therapy for tuberculosis (fresh air, space, and sunlight) before more technical and advanced medical treatment was discovered. Sadly, to the poor man’s disadvantage, sanatoriums were not widely available and often required payment beyond their means (Tuberculosis in Europe and North America, 1800–1922).

It is shocking to learn that of all the deaths among all nationalities during the years of 1900-1903, 3.35% of the deceased were Irish. It is truly something to think about, as the Irish composed only about 12% of the population, yet they comprised a statistically significant portion of tuberculosis deaths (Irish 1840’s – 1910.” Cincinnati: A City of Immigrants). Also, it is important to remember that this is simply one of the many diseases that the Irish had to combat. Analyzing these records paints the picture of the worst the Irish emigrants faced. However, they still managed to find ways to flourish in dismal conditions and perhaps that is why Irish emigrants continued to pursue the “American Dream.”

Bibliography

Buckley, Dan. “The silent terror that consumed so many.” Irish Examiner. August 23, 2010. Accessed March 28, 2017. http://www.irishexaminer.com/ireland/health/the-silent-terror-that-consumed-so-many-128709.html

“Cincinnati Birth and Death Records, 1865-1912.” Digital Collections and Repositories @ UC Libraries. Accessed March 28, 2017. http://digital.libraries.uc.edu/collections/birthdeath/

Figueroa-Munoz, Jose I., and Pilar Ramon-Pardo. “Tuberculosis control in vulnerable groups.” WHO. September 2008. Accessed March 28, 2017. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/9/06-038737/en/

Guyer, Bernard, et al. “Annual Summary of Vital Statistics: Trends in the Health of Americans During the 20th Century.” Pediatrics 106, no. 6 (December 2000): 1307. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed March 28, 2017)

“Irish 1840’s – 1910.” Cincinnati: A City of Immigrants. Accessed March 28, 2017. http://www.cincinnati-cityofimmigrants.com/irish/

Mandal, Ananya, MD. “History of Tuberculosis.” News-Medical.net. February 03, 2014. Accessed March 28, 2017. http://www.news-medical.net/health/History-of-Tuberculosis.aspx

Murray, John F., Dean E. Schraufnagel, and Philip C. Hopewell. “Treatment of Tuberculosis. A Historical Perspective.” Annals of the American Thoracic Society 12, no. 12 (December 12, 2015): 1749-759. Accessed March 28, 2017. doi:10.1513/annalsats.201509-632ps

“Tuberculosis in Europe and North America, 1800–1922.” Open Collections Program: Contagion, Tuberculosis in Europe and North America, 1800–1922. Accessed March 28, 2017.