The UC Campus in Wartime

The initial impact felt by the student body at the outset of America’s entry into World War II was the need to support the country in its efforts to defend freedom. Organizers of a UC-Xavier scrap drive in the fall of 1942 asked each student to contribute one pound of rubber and metal scrap each day to benefit the war effort. UC’s scrap haul of 150,000 pounds was auctioned to the highest bidder and the proceeds went to war charities and a memorial to UC students and faculty serving in the armed forces. President Raymond Walters urged students to defer action when deciding on how to serve their country and to wait to see what the plans of the military would be concerning men currently enrolled in college and ROTC.

Selective Service deferments and age restrictions as well as the maintenance of the ROTC programs allowed UC to sustain a decent enrollment through 1942, but when the minimum age for the Selective Service was lowered to 18 on November 13, 1942, the campus began to feel the loss of many male students who went off to defend their country. Some activities were greatly impacted or cancelled altogether, including the 1943-44 football season. Students remaining on campus contributed to the war effort as well, organizing additional scrap drives and offering support to the armed forces.

In the summer of 1944, the staff of the News Record created a four-page mimeographed version of the paper to send to students serving in the war. Dubbed the “News Record Jr.,” the masthead included a whimsical image of a soldier baby spilling ink. Letters from soldiers who received the publication attest to their appreciation of this connection with the homefront.

This headline in the News Record announces the cancellation of the 1943-44 football season.

Scrap collected during the UC-Xavier scrap drive of 1942 and “News Record Jr.”

The Army Student Training Program

The Army Student Training Program (ASTP) was a federally sponsored program designed to create a pool of specially trained soldiers from which the Army could select men for placement in positions requiring technical, medical, and language and area expertise. The first ASTP men arrived at UC on March 1, 1943 and the program reached a maximum enrollment of 1,454 soldier-students.

The need to house, feed, and instruct the soldier-students caused much displacement of civilian students, faculty and staff and disruption of regular campus life. Classes were held in old McMicken Hall, where some cadets were also housed in makeshift barracks, complete with bathroom facilities. Other men lived in Memorial Dormitory or fraternity houses leased by the program. With so many men going off to war, including professors, young female instructors were the norm for academic classes but they were sometimes thought to be a distraction to the students.

While the program lasted longer than the SATC, it proved to be short-lived as well, with only 131 men remaining at UC by March 1944. The Army simply needed more men to fight and the ASTP men were sent to active duty. But while it lasted, the presence of the ASTP men allowed many of the student organizations to say alive and maintained a social life for the co-eds and the few men who remained on campus.

ASTP Air cadets in a Geography class

Classrooms in McMicken Hall converted to ASTP barracks . ASTP men also lived in fraternity houses.

Veterans Return

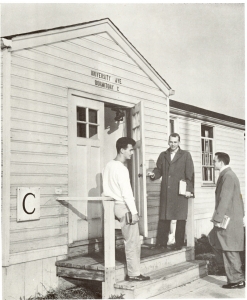

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the GI Bill, offered veterans amazing opportunities to enroll in higher education and many took full advantage of the program. The influx of veterans enrolling at the University created a severe housing shortage on campus. Temporary dorms were constructed in 1946 to house single veterans who had previously been housed in fraternity houses. “The Barracks,” as they were known, were situated on the property bounded by University Avenue, Scioto Street and Daniels Street, on the present site of Schneider and Turner Halls.

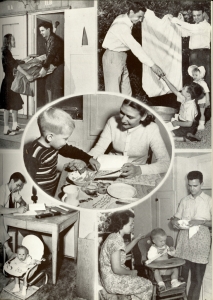

Veterans with families had special housing needs that the University felt it had to address before granting them admission. Sensing a “patriotic obligation to provide educational facilities for returned servicemen” the board contracted with the Federal Public Housing Authority to provide 18 portable units on the space between Memorial Hall and the YMCA building, which would become affectionately (or not) known as “Vetsville.” The units were complete by mid-November 1945 and by December 7, 34 veterans and their families resided in their new 20′ x 20′ homes. While the GI Bill provided veterans with families $75/mo. for living expenses, the Vetsville rental fee, which included furnishings and utilities and the use of laundry facilities, was an affordable $30/mo.

Housing wasn’t the only place where UC was bursting at the seams. The University leased five former World War II barracks in 1947 to use as temporary classroom buildings to accommodate the increase in enrollment following the war. Three buildings were situated in front of the Physics building and two were between Teachers College and the old Biology-Pharmacy building. The buildings were razed in 1957.

“The Barracks” housing for single vets

Scenes from “Vetsville”

Educational Programs and Services for Veterans

The University published this brochure to inform veterans of the opportunities available to them. The complete brochure is available as a pdf file.

Temporary classrooms in front of the Physics building