Seneca the Younger (ca. 4 BCE-65 CE) is a controversial figure in the political, literary, and philosophical history of Rome. Seneca was a remarkably versatile and prolific writer whose life was affected by several emperors from Tiberius to Nero. Claudius caused his exile from Rome and Nero his death. Seneca wrote a large collection of letters, full of memorable quotes (e.g., “If you live in harmony with nature you will never be poor; if you live according to opinion, you will never be rich,” quoting Epicurus, 16) and thoughtful philosophical essays about anger, death (shortness of life), leisure, the happy life, and tranquility, and also rather gruesome tragedies such as Medea and Thyestes, and even a satire with the impossible title Apocolocyntosis [instead of Apotheosis] divi Claudii (The Gourdification of the Divine Claudius) as well as a work on cosmology, meteorology, and astrology/astronomy. The main controversy stems from the seeming inconsistency of his adhering to a Stoic philosophy of decency, moral awareness, mindfulness, and moderation juxtaposed to his defense of the murderous dictator Nero and his own amassing of considerable wealth and power.

Seneca was appropriated already in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages as a “pre-Christian” although there is no reason to think that he was anything but a non-religious pagan. Christianity as well as Buddhism and other religions have aspects in common with Stoicism. Unfortunately, Stoicism has in recent years also been appropriated by unsavory characters such as white supremacists and misogynists based on some anti-woman and pro-slavery statements expressed by some ancient Stoics, though not by Seneca or by most Stoics in antiquity. On a more positive note, an organization, “Modern Stoicism,” has been conducting a “Stoic Week” experiment online since 2013, beginning as a workshop at the University of Exeter in 2012 (see below), to teach us all how to handle life (and, for Seneca, death) better, and how to be more contented and fulfilled. It is a “self-help” program that its proponents claim works.

The evening began with a stimulating panel discussion featuring James Romm, Bard College, Christopher Trinacty, Oberlin College, and, via Zoom, Gareth Williams, Columbia University, all world-leading experts on Seneca. The panel was introduced by the chair of the UC Classics Department Daniel Markovich and moderated by Adam Kamesar, Hebrew Union College. The latter has taught several courses on Seneca at HUC.

Some questions addressed included the personal engagement with Seneca of each panelist and whether their research and understanding of Seneca had developed and, if so, how. Professor Romm was asked to address what he deemed to be important elements for the study of Seneca from a historical perspective, Professor Trinacty was asked to address the question from the perspective of philosophy, and Professor Williams from the perspective of literature. A political perspective had to wait for a question from the audience addressed by Professor Romm who drew parallels to the former U.S. President Trump and some supposedly decent people around him who condoned and committed crimes seemingly out of fear and/or because of corruption through power and money.

Next, Yo Shionoya, DMA candidate at the UC College Conservatory of Music, led a chamber ensemble performing two carefully selected and immensely beautiful pieces by Dmitri Shostakovich, “Elegy” from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, Op. 2, composed during the murderous dictatorship of Joseph Stalin, and “Secret Signs” from Seven Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok, Op. 127, composed after the death of Stalin. The virtuoso musicians included Pin-Hsuan Chen on the violin, Yo Shionoya on the oboe, Yen-Ju Young on the viola, and Abigail Leidy on the cello.

Then followed an interesting interdisciplinary and interdepartmental panel featuring undergraduate students from UC presenting their experiences of having lived “the life of a Stoic” for one week. Shreya Pandey (sophomore, Engineering), Justin Dooley (junior, Classical Civilization), Shuta Maeno (senior, Philosophy), Michael Shobe (junior, Classics), Hunter Torosian (junior, Classics), Lauren “Roo” Mason (senior, Philosophy) shared their impressions and took several questions from the audience. This panel was moderated by Daniel Markovich who had previous experience from conducting the Stoic Week experiment in his undergraduate classes.

The students summarized various exercises they had performed regarding emotions, resilience, the value of friendships, nature and community, and identity and character; for example, drawing concentric circles by whom they considered closest to them and progressively farthest away, answering such questions as whether we have obligations to people on the other side of the world (e.g., Israel and Ukraine) and if we owe anything to other species of life on Earth (e.g., mass extinctions of animal species as a direct result of human activity)? Another exercise was to compose lists of qualities that each student thought were important to be a “good” person; for example, honesty, strength, and patience followed by another list enumerating things they considered to be important for having a good life; for example, family, friends, comfort, health, wealth, fame, a good education, a good job, a nice house, etc., then asking themselves if they could still be a good person if they didn’t have these things. Another exercise was to divide events or situations into two columns and list which things are and are not under a person’s control. For example, imagine that you are going to have an exam and the bus to get to UC is late which in turn makes you late for the exam. This is not under your control; though, for example, choosing to leave early on exam day is. Subsequently, the participants were asked to imagine that when they wake up in the morning, to think of things that might “go wrong” that day, and if and what they could do about them and to think about what parts of things going wrong are not under their control. The students said that they believed that Stoicism could help them become happier and more resilient and to live life more intentionally and mindfully.

If you wish to participate in the official global Stoic Week, there is still time to register! The 2023 Stoic Week is scheduled for November 6-12. https://modernstoicism.com/stoic-week-2023-6-12-november-2023-learn-more-and-register/

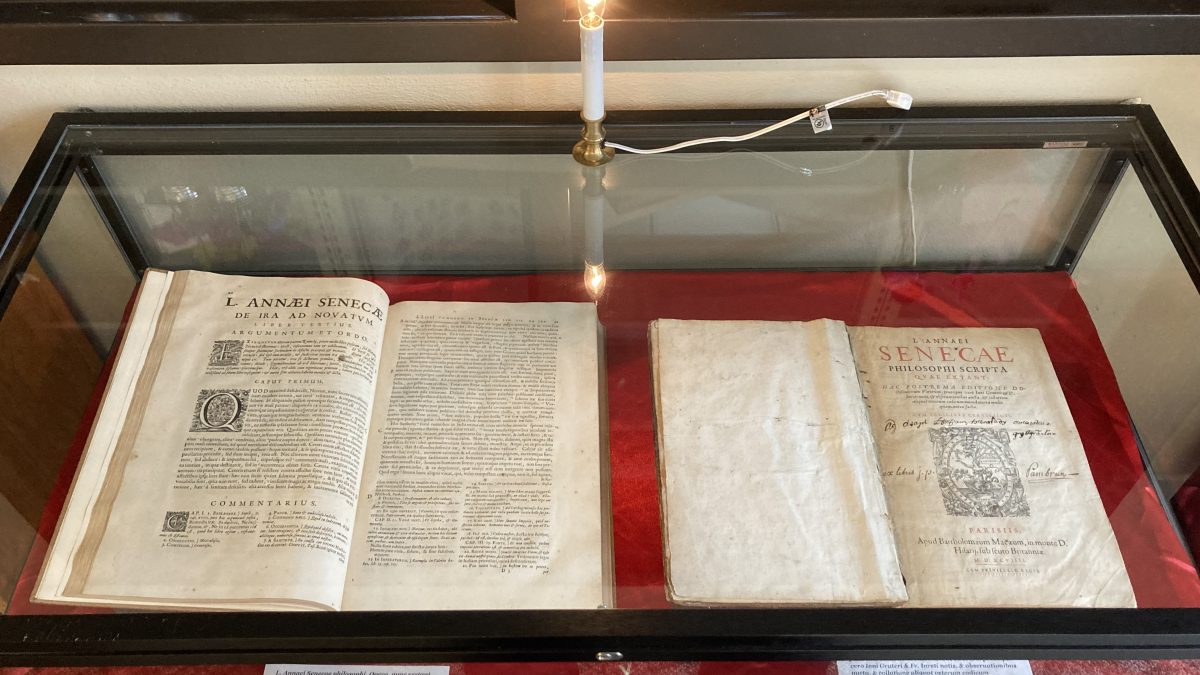

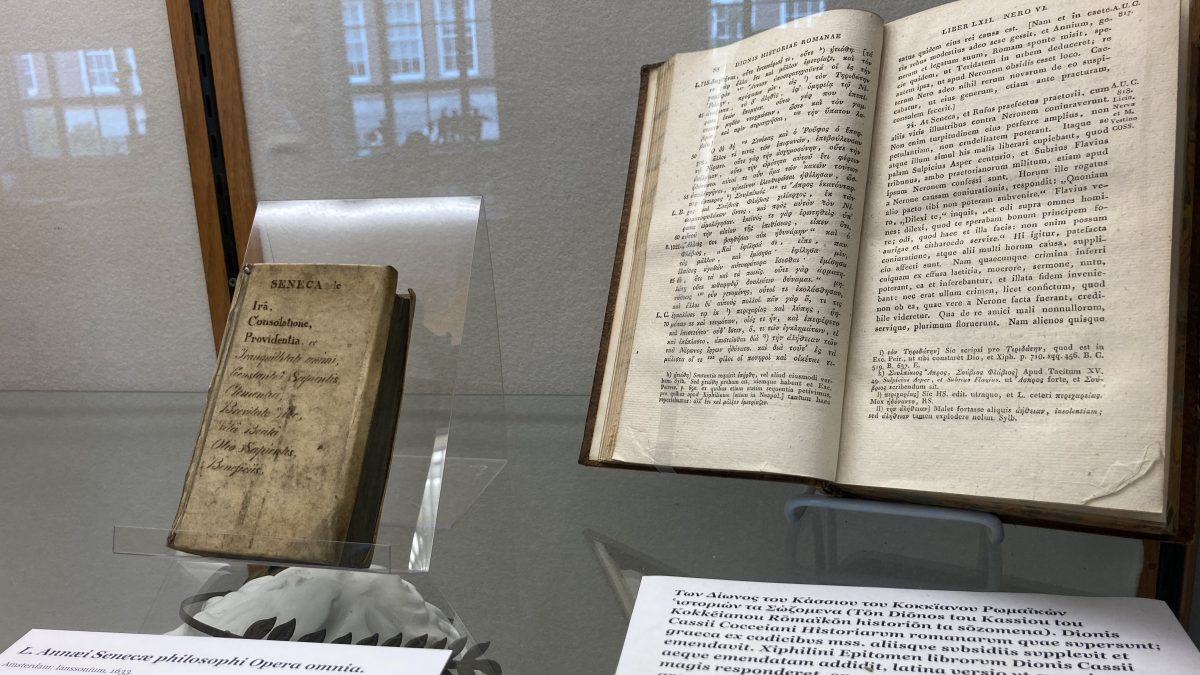

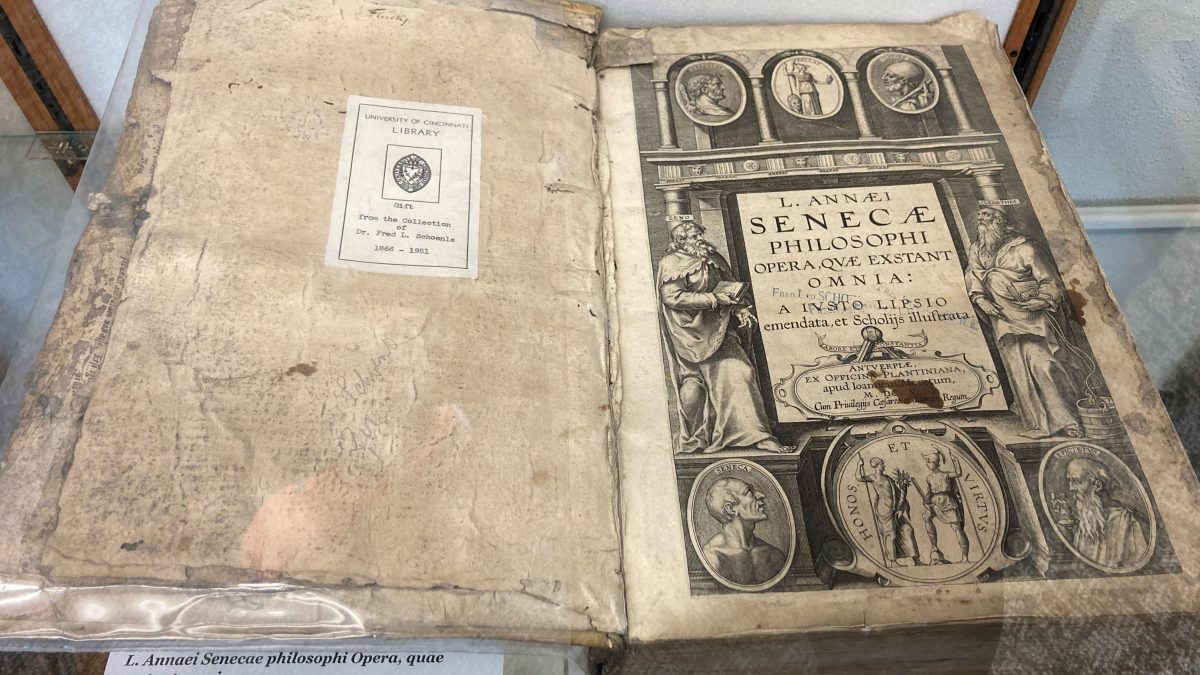

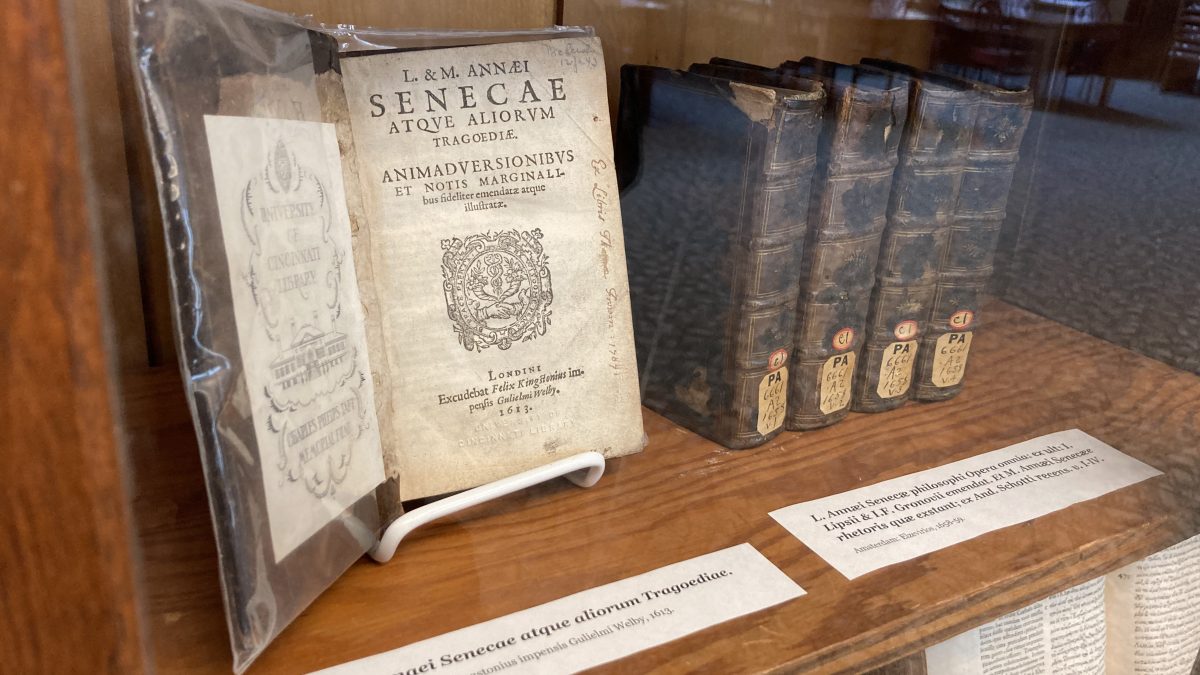

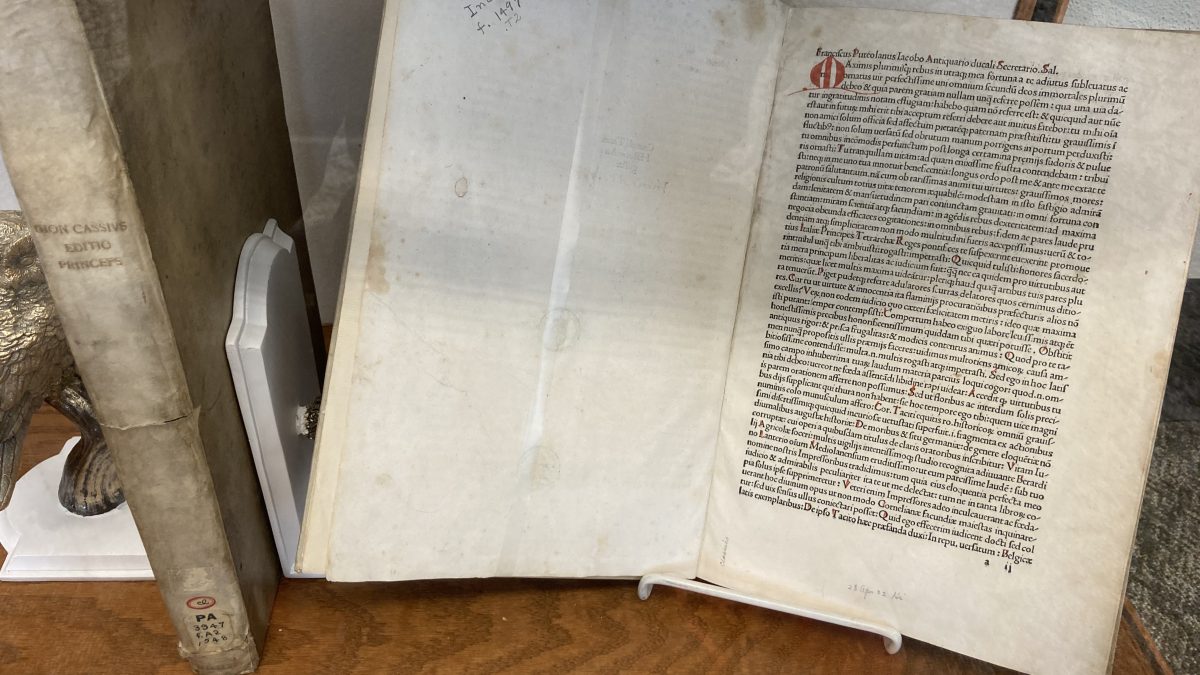

An exhibition in the Burnam Library featured a 1599 Paris Gruterus edition, a 1610 Antwerp Lipsius second edition, a 1675 Lipsius fourth edition with engravings by Rubens of a portrait bust of Seneca and of him dying in the bath, and a 1658 4-volume Elzevir Gronovius edition, all early critical editions of Seneca’s philosophical writings, and an incunable from 1497 of works of Tacitus, a chief source of Seneca’s biography, and an original Roman copper coin of emperor Nero, and much, much more.

The jam-packed and well-attended program concluded with a tasty reception of Mediterranean delectables such as hummus, tabbouleh, baba ghanoush, olives, and pita bread from Ruth’s Parkside Café and Italian salads from Whole Foods.

One of Seneca’s countless insights, this one from his Natural Questions (7):

“The time will come when diligent research over long periods will bring to light things which now lie hidden. A single lifetime, even though entirely devoted to the sky, would not be enough for the investigation of so vast a subject… And so this knowledge will be unfolded only through long successive ages. There will come a time when our descendants will be amazed that we did not know things that are so plain to them… Many discoveries are reserved for ages still to come when the memory of us will have been effaced.”

This one from his essay On the Shortness of Life (9):

“Putting things off is the biggest waste of life: it snatches away each day as it comes and denies us the present by promising the future. The greatest obstacle to living is expectancy, which hangs upon tomorrow and loses today. You are arranging what lies in Fortune’s control, and abandoning what lies in yours. What are you looking at? To what goal are you straining? The whole future lies in uncertainty: live immediately.”

For those interested in learning more about Seneca, here are a few works on the subject by the panelists:

Romm, James S. (2020). How to Give: An Ancient Guide to Giving and Receiving. Seneca; selected, translated, and introduced. Princeton University Press.

_______________ (2019). How to Keep Your Cool: An Ancient Guide to Anger Management. Seneca; selected, translated, and introduced. Princeton University Press.

______________ (2018). How to Die: An Ancient Guide to the End of Life. Seneca; edited, translated, and introduced. Princeton University Press.

______________ (2014). Dying Every Day: Seneca at the Court of Nero. New York: Albert and Knopf.

Trinacty, Christopher (2022). Seneca: Natural Questions: Selections. Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Dickinson College Commentaries.

_____________________ (2016). “Imago res mortua est: Senecan Intertextuality,” pp. 11-33. Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Senecan Tragedy: Scholarly, Theatrical and Literary Receptions, edited by Eric Dodson-Robinson. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

_____________________ (2015). “Senecan Tragedy,” pp. 29-40. The Cambridge Companion to Seneca, edited by Shadi Bartsch, University of Chicago; Alessandro Schiesaro, Sapienza, University of Rome. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

_____________________ (2014). Senecan Tragedy and the Reception of Augustan Poetry. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Williams, Gareth D. (2015). “Style and Form in Seneca’s Writings,” pp. 135-149. The Cambridge Companion to Seneca, edited by Shadi Bartsch, University of Chicago; Alessandro Schiesaro, Sapienza, University of Rome. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

__________________ (2012). The Cosmic Viewpoint: A Study of Seneca’s Natural Questions. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

__________________, and Katharina Volk, eds. (2006). Seeing Seneca Whole: Perspectives on Philosophy, Poetry and Politics. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

The event was organized by Rebecka Lindau, the John Miller Burnam Classics Library, and Professor Susan Prince, the UC Classics Department, with financial support from the UC Classics Department and the University of Cincinnati Libraries.