Managing University Archives in a Digital World

By Eira Tansey, Digital Archivist/Records Manager, Archives and Rare Books Library

“What College-Conservatory of Music musicals were staged in 1986?”

“When did the university begin offering a dental insurance plan?”

“What dorms have served as polling places?”

These are just a handful of the university-history related questions I’ve encountered since starting work at the Archives and Rare Books (ARB) Library nearly five years ago. The questions we receive concern events at all times in campus history – from the earliest days of UC’s predecessor colleges to events that took place just a couple years ago.

ARB is the official home for University Archives, making us the obvious place to go for answers about university history. But our archives do not instantly materialize – they require diligence and work to ensure records are not lost. Anyone who has ever tried to research their family genealogy knows the woes of promising clues leading to a trail that quickly turns cold. Maybe the records in question were lost in a fire, or were simply never maintained because someone didn’t understand their value for future users.

Thanks to diligent faculty, staff and students who have done much work over the years to send us records, photographs and other documents, University Archives can answer most questions we receive about the last two centuries of the university’s history. But today we run the risk of losing our university’s third century of history.

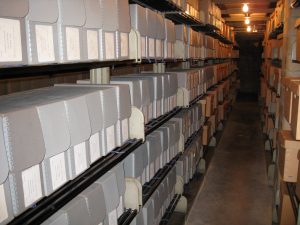

Since ARB was created, the main way in which University Archives receives content has been departments dropping off boxes of paper records. We then organize the contents of each box (what archivists call “processing”) and inventory them (creating a “finding aid”). The processed boxes then go into our secure archival stacks, where they are ready to be retrieved when needed by a user.

The vast majority of today’s content that will be tomorrow’s archives is created in diverse technologies. Most photographs are no longer developed in darkrooms; rather, they are manipulated in Photoshop. Reports are no longer printed and bound, they are distributed via PDF. And when was the last time you wrote a formal memo? E-mails are the new memos.

Per the university’s official records management policy, departments are required to periodically send specific records to University Archives to ensure continuity in preserving university history. The reality is that in the past, it was often easier to comply with those guidelines than it is today. In a paper-based environment, at some point transferring files was inevitable thanks to a move to a new building or the filling up of filing cabinets. Today, there is no equivalent digital “trigger event” of a physical move or full storage that forces departments to think, “Hey, it’s time to send these files to University Archives.” There are many different file storage systems across campus, and unfortunately there are almost no options to automate collecting relevant archival records from the university’s various colleges and administrative units.

As the University of Cincinnati Libraries’ digital archivist/records manager, I am responsible for issuing both guidance for records while they are still in the custody of departments around the university and managing the processing of “born digital” records that are transferred to University Archives. As a result, I often see how even though departments are advised to transfer records to us, they struggle to do this as regularly as we would like to see happen.

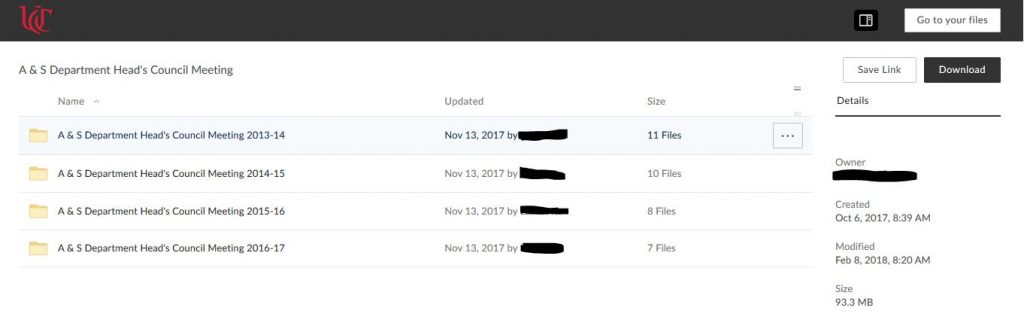

I’m pleased to report, however, that this is not an insurmountable challenge. One of the creative ways that university staff and I have found to be the easiest way to transfer records is through UC Box, the file sharing system the University of Cincinnati adopted recently. Within Box, UC affiliates can easily send their records to me. Here is an example from the College of Arts and Sciences administrative office:

After I receive the files through Box, I still have to process the files. What does it mean to process born-digital files? It depends. The first thing I do is to make a local “preservation copy” of all the files that are transferred, and place them into secure digital storage outside of Box, on the Libraries’ digital collections server. I then create a “processed copy” of all the files that are intended for public use – similar to the boxes of paper files we keep on the shelves of University Archives that we pull upon request. This is a bit like putting your original birth certificate into a bank safe deposit box, while you keep a photocopy at home in your personal records.

If it’s a potentially sensitive set of records, I might do a close review of the files to ensure no confidential information is being disseminated that needs to be kept private. The processed files are usually very similar to preservation files, with some minor changes to enable public use.

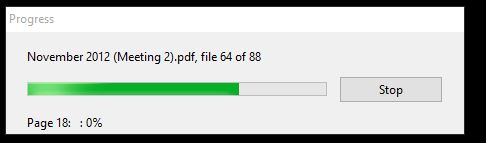

During processing, there is a lot of waiting while running various tasks on large groups of files. This is a pretty common sight in my working life:

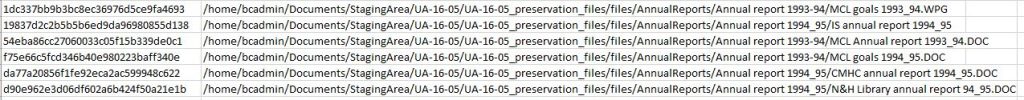

At the end of the process (and often, much earlier) I will run what is known as hashing or checksumming of the files. A hash, or checksum, is an algorithmic process run on a file to generate a unique alphanumeric number for that file. If anything changes within the “guts” of the file – whether the deletion of a period at the end of a sentence, a changed pixel in a photo, or snipping of a half-second of audio – then the entire checksum will change for the file. Digital archivists will generate a checksum for files when they are received, and will generate them again on a periodic basis. If they match, this is how archivists can demonstrate that the file has not suffered from any corruption or change.

Finally, I publish a finding aid for all processed born-digital collections. Many archives with born-digital collections are exploring unique ways to enable user access to these records. Some have set up “virtual reading rooms” while others simply deliver the files through a file sharing system or email. We are still figuring this part out at the University of Cincinnati Libraries.

Digital archivists deal with a paradox of living in a digital deluge (where it is far easier to create new documents than 40 years ago), but also battling a digital dark age (where without early intervention in archiving files, they can risk being lost or corrupted). It may seem like the digital transition has changed everything about archivists’ work, but the recipe for success remains the same – building relationships across the university, investment in infrastructure and always looking for creative ways to solve problems.