Written by Laura Laugle, Berry Project Archivist

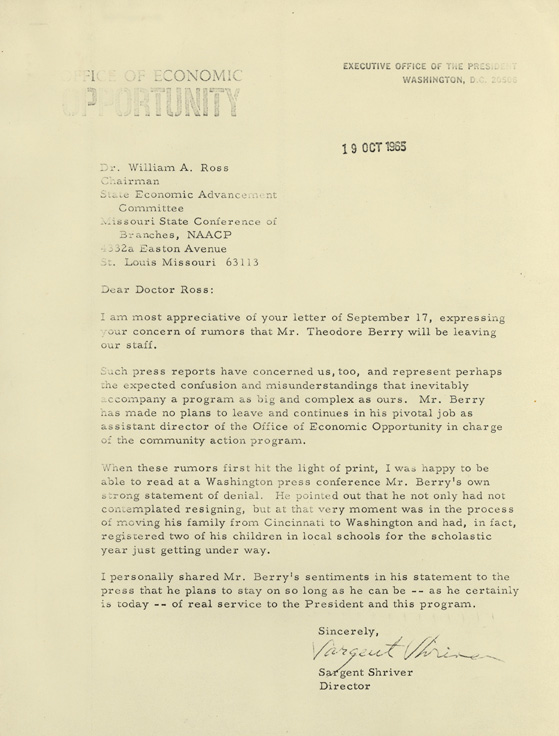

I’d like to start out this post with a few words for a man with whom Theodore Berry worked closely during his tenure at the Office of Economic Opportunity, R. Sargent Shriver Jr. During the upheaval accompanying the creation of the program and amid controversy over lost memoranda, Shriver stood by his choice of Berry as director of the Community Action Program and continued to be a friend and supporter of Berry’s long after they had both left Washington when President Nixon took office. Shriver was not only the first director of the Office of Economic Opportunity, but was also the first director of the Peace Corps and helped his wife, Eunice Kennedy Shriver, develop and found the Special Olympics in 1968. Shriver died last Tuesday, January 18, 2011 in a Maryland hospital at the age of 95 and was remembered at his funeral on Friday, January 21 by his five children, his nineteen grandchildren and a horde of celebrities and dignitaries from all over the world as a loving family member and friend and a true statesman.

This past week I’ve come across some of the oldest and in my opinion, most interesting documents in the collection. As a student of Germanic languages and culture, I’ve always been horrified and fascinated by the causes and happenings of World War II. My own education has centered almost entirely on the whats, whens, whys, wheres and hows of early 20th century Europe and not on American involvement in the War, let alone the contribution of African-Americans to the effort. In fact, I am ashamed to say that my sole education on this subject comes from a made for television production by the BBC called Small Island in which American soldiers are portrayed as violent bigots who attempt to force segregation in England in spite of its illegality in Britain. I have no way of knowing if this is an accurate depiction of the majority American soldiers on the front lines during WWII, but I’d like to think not. However, if Berry’s experience is anything to go by, the politicians back home in Washington were only slightly less racist and considerably more deceitful than those brutish fictional characters.

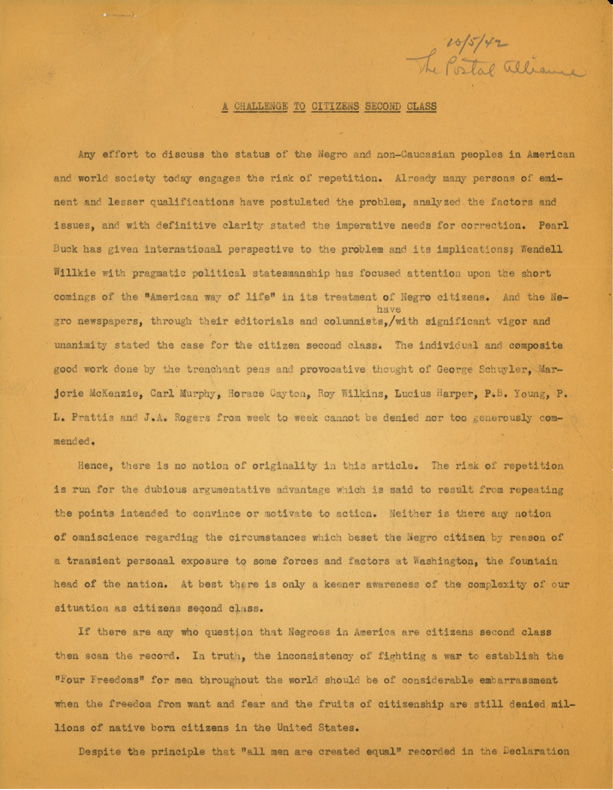

Berry worked in the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration as Liaison Officer for Group Morale responsible for the “negro problem” in the Office of War Information and the Office of Facts and Figures from February 1942 until he resigned the post in August of the same year. As one may guess from his speedy departure from the agency, it became clear to Berry very quickly that the federal government was not the place for him. In fact, it would be clear to anyone reading the correspondence in the Berry Collection that the federal government had absolutely no intention of making any substantial changes in the lives of its African-American soldiers.

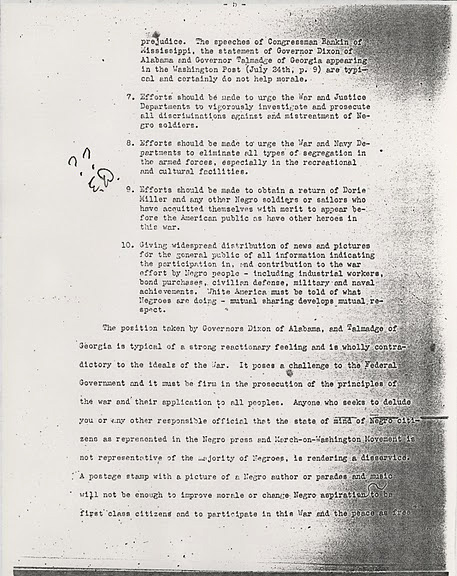

Of Berry’s many complaints, one of the most well documented was of the attempts made by the OWI and the OFF to use propaganda to bolster support among African-Americans without actually doing anything to resolve the real and justified grievance that the African-American community had with the American Armed Forces. This problem of propaganda taking precedence over actual progress was compounded when, according to a letter from Berry to Earl Brown of Time and Life Magazines “… a certain white gentleman was permitted to attach himself to the Office as a dollar-a-year-man and supposedly qualified as a consultant on Negro matters… The man in question was qualified for this position only because of the fact that he was the owner and operator of a chain of theatres which catered to Negro clientele in certain Southern communities.” That man is Martin Starr. In a letter to Walter White of the NAACP Berry explains that, though Starr was only unofficially attached to the agency in an advisory role, Starr was frequently allowed by the administration to usurp power from Berry in order to enact his own version of a Negro Morale Program. Starr continually acted as an official Liaison Officer without Berry’s consent and often sent his recommendations for the development of the Negro Morale Program to agency managers directly without even consulting Berry for comment. In his report to OWI director, Elmer Davis, Berry suggested a wide variety of ways to address the issues at the root of the “Negro morale problem,” most notably, a complete prohibition of segregation in the armed forces and ending the blind-eye racism evident at all levels of all branches. Conversely, Starr advocated a campaign of scare tactics and propaganda; calling for the reprint of the syndicated Chandler Owens article “What Will Happen to Negroes if Hitler Wins?” and the promotion of “All American News,” a newsreel made for African-American cinemas, like those owned by Starr, depicting blacks participating in the war effort and which, according to William H. Hastie of the War Department, were “used as a substitute for the normal presentation of news worthy events involving Negroes along with other news worthy occurrences in the regular newsreels.” In short, the administration seems to have used Berry as a puppet – a black man placed in high office not to be given any power for the betterment of his people, but to be used as a pacifier to placate the African-American troops and populace while the status-quo was quietly protected behind the scenes.

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $61,287 grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the Archives and Records Administration to fully process the Theodore M. Berry Collection in the Archives & Rare Books Library. All information and opinions published on the Berry project website and in the blog entries are those of the individuals involved in the grant project and do not reflect those of the National Archives and Records Administration. We gratefully acknowledge the support of NARA.