Titus Lucretius Carus was presumably born on October 15 (99 BCE), i.e., today 1,919 years ago (Virgil, too, was supposedly, though somewhat unlikely, born on the same day, October 15, 70 BCE; however, he will have to wait for a blog until next year or in 2020)! So we wish to honor this amazing Roman poet and Epicurean philosopher. His only known work is De rerum natura, On the Nature of Things, but what a poetic work it is. Although it influenced later thinkers, it had an impact already on contemporary poets such as Vergil and Horace. Cicero, too, was a great admirer as witnessed in a letter to his brother Quintus (QFr. 2.9):

“Lucreti poemata, ut scribis, ita sunt, multis luminibus ingeni, multae tamen artis.“

“The poetry of Lucretius is, as you say in your letter, rich in brilliant genius, yet highly artistic.”

Ovid’s review of the DRN in his Amores (1.15.23–24) is famous:

“Carmina sublimis tunc sunt peritura Lucreti exitio terras cum dabit una dies.”

“The verses of the sublime Lucretius will perish only when a day will bring the end of the world.”

The didactic poem, written in some 7,400 dactylic hexameters, is divided into six books, and explores Epicurean thought through metaphors, alliteration, assonance, archaisms. It echoes Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Callimachus, even Thucydides and in epic diction and style, “the father” of Latin epic verse, Quintus Ennius. The poem is full of contradictions — archaic form combined with modern thought, idyllic nature imagery with dystopia and misanthropy, anti-religious sentiments with elements of prophesy and salvation, and prosaic methodology with poetic sensibility.

In books I and II Lucretius presents the principles of atomism. Lucretius and Epicurean philosophy following Democritus atomic theory of the universe argue that nature consists of indivisible and unchanging elements, atoms, whose movements and combinations give rise to the perceived world. The movements of the atoms occur according to strict mechanical principles or laws without divine intervention. Anyone who has embraced this teaching no longer should fear omens or divine punishment, or death or hell, since they would know that even the soul consists of atoms and that it is dissolved along with the body upon death. Books I and II further polemicize against the pre-Socratic philosophers Heracleitus, Empedocles, and Anaxagoras and the rival Stoic school. For example, Lucretius argues against those who believed that fire was the Uhr element and rejects the notion of a pre-Socratic First element altogether (1.690-712 and 1.772-781).

“Quapropter qui materiem rerum esse putarunt ignem atque ex igni summam consistere posse, et qui principium gignundis aera rebus constituere, aut umorem quicumque putarunt fingere res ipsum per se, terramve creare omnia et in rerum naturas vertier omnis, magno opere a vero longe derrasse videntur. adde etiam qui conduplicant primordia rerum, aera iungentes igni terramque liquori, et qui quattuor ex rebus posse omnia rentur ex igni terra atque anima procrescere et imbri” (1.705-716).

“Therefore those who have thought that fire is the material of things and that the universe can consist of fire, and those who have laid down that air is the prime element for producing things, or whoever have thought that water molds things by itself, or that earth produces all things and changes itself into the natures of all things, are seen to have gone far astray from the truth. Add, moreover, those who take the first-beginnings of things in couples, joining air to fire and earth to water, and those who think that all can grow forth out of four things, from fire, earth, air, and water.”

Book III explores the nature of the mind (animus) or central consciousness and the soul (anima) or sensation and explains that the soul is born and grows with the body, and that at death it dissipates like “smoke”; book IV discusses sensation and thought (sight, hearing, taste, smell, sleep and dreams) and V, for me the most interesting book, describes how the world came about and its inner workings as well as the evolution of life and human society. Lucretius delineates cultural and technological developments of humans such as the use of tools from prehistory to Lucretius’ own time. He theorizes that the earliest tools were hands, nails and teeth followed by stones, branches and fire. Copper and then bronze tools were used to till the soil until the bronze sickle was replaced by the iron plow. Lucretius suggests that the smelting of metal, and perhaps too the firing of pottery, was discovered by accident; for example, as a result of a forest fire. Before technology, Lucretius saw human life as lived “in the fashion of wild beasts roaming at large,” which, according to recent anthropological findings, is most likely a fairly accurate description of early humans (see, e.g., Donna Hart & Robert W. Sussman, Man the Hunted: Primates, Predators, and Human Evolution. New York: Westview Press, 2005).

“Necdum res igni scibant tractare neque uti pellibus et spoliis corpus vestire ferarum, sed nemora atque cavos montis silvasque colebant, et frutices inter condebant squalida membra verbera ventorum vitare imbrisque coacti” (5.953-957).

“Not yet did they know how to work things with fire, nor to use skins and to clothe themselves in the strippings of wild beasts; but they dwelt in the woods and forests and mountain caves, and hid their rough bodies in the underwoods when they had to escape the beating of wind and rain.”

Later rudimentary huts were built and the use and kindling of fire discovered along with the creation of clothing, language, family life, city-states, and the arts; the final book VI describes and explains various celestial and terrestrial phenomena (thunder, hail, ice, wind, earthquakes, agriculture). The poem ends with a description of the plague of Athens in 430 BCE, although since the poem is unfinished we cannot be certain that it was intended to end this way even though it juxtaposes nicely with the birth of spring and Venus’ creation with which the poem opens.

Omnia denique sancta deum delubra replerat corporibus mors exanimis, onerataque passim cuncta cadaveribus caelestum templa manebant, hospitibus loca quae complerant aedituentes.nec iam religio divom nec numina magni pendebantur enim: praesens dolor exsuperabat. nec mos ille sepulturae remanebat in urbe, quo prius hic populus semper consuerat humari; perturbatus enim totus trepidabat, et unus quisque suum pro re et pro tempore maestus humabat. multaque res subita et paupertas horrida suasit; namque suos consanguineos aliena rogorum insuper extructa ingenti clamore locabant subdebantque faces, multo cum sanguine saepe rixantes potius quam corpora desererentur (6.1272-1286).

“Moreover, death had filled all the sanctuaries of the gods with lifeless bodies, all the temples of the celestials everywhere remained burdened with corpses, all which places the sacristans had crowded with guests. For indeed now neither the worship of the gods nor their power was much regarded: the present grief was too great. Nor did that custom of sepulture remain in the city, with which this nation in the past had been always accustomed to be buried; for the whole nation was in trepidation and dismay, and each man in his sorrow buried his own dead as time and circumstances allowed. Sudden need also and poverty persuaded to many dreadful expedients: for they would lay their own kindred amidst loud lamentation upon piles of wood not their own, and would set light to the fire, often brawling with much shedding of blood rather than abandon the bodies.”

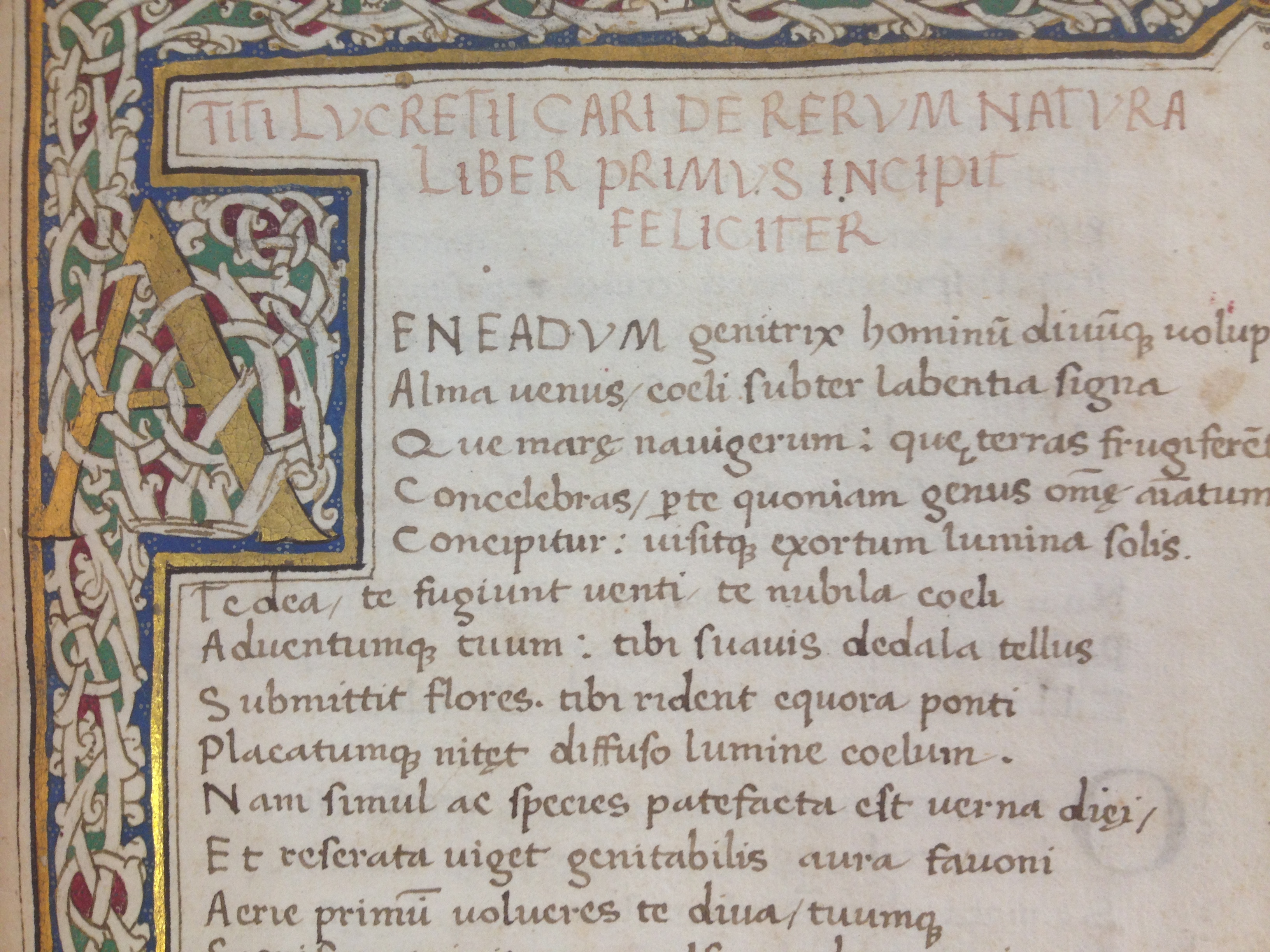

In spite of the Epicurean unorthodox view of divinity, De rerum natura as an epos follows the model of Homer and its imitators and begins with a celebration of the divine, not the Muses as in Homer and Virgil, or Stoic Zeus/Jupiter as in Ennius and Seneca, but the goddess of love, Venus, the mother of Aeneas and Rome and the creative force behind all of nature’s things.

“Aeneadum genetrix, hominum divomque voluptas, alma Venus, caeli subter labentia signaquae mare navigerum, quae terras frugiferentis concelebras, per te quoniam genus omne animantum concipitur visitque exortum lumina solis: te, dea, te fugiunt venti, te nubila caeli adventumque tuum, tibi suavis daedala tellus summittit flores, tibi rident aequora ponti placatumque nitet diffuso lumine caelum. nam simul ac species patefactast verna dieiet reserata viget genitabilis aura favoni, aeriae primum volucres te, diva, tuum que significant initum perculsae corda tua vi. inde ferae, pecudes persultant pabula laetaet rapidos tranant amnis: ita capta lepore” (1.1-15).

“Venerable Venus, Mother of Aeneas, pleasing to gods and humans, who beneath the smooth-moving heavenly signs fill with yourself the sea teaming with ships, the earth that bears the crops, since through you every kind of living thing is conceived and rising up looks on the light of the sun: from you, O goddess, from you the winds flee away, the clouds of heaven from you and your coming; for you the wonder-working earth puts forth sweet flowers, for you the wide stretches of ocean laugh, and heaven grown peaceful glows with outpouring light. For as soon as the vernal face of day appears, and the breeze of the teeming west wind blows fresh and free, first the birds of the air proclaim you, divine one, and your advent, pierced to the heart by your might. Next wild creatures and farm animals dance over the rich pastures and swim across rapid rivers: so greedily does each one follow you, held captive by your charm.”

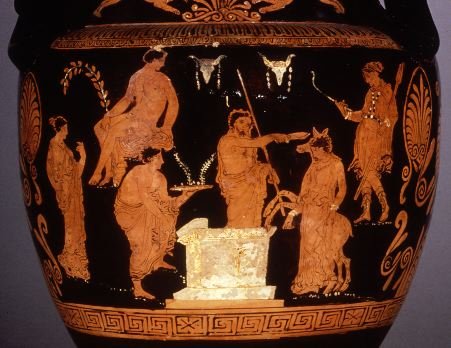

In spite of his beautifully crafted recognition of nature and the goddess Venus, Lucretius is frequently thought of as an atheist because he described the universe as operating according to physical principles, guided by fortuna, “chance” rather than by divine intervention. For Lucretius the exemplum he uses to illustrate the absence of divine intervention and the horrible affects religion and superstition can have on mortals is the sacrifice to the goddess Artemis of Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, to obtain favorable winds to allow the Greek fleet to sail against Troy (to read this passage, see an earlier blog celebrating Artemis’ birthday https://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/liblog/2018/04/may-6-birthday-of-the-goddess-artemis-happy-thargelia-and-apollos-birthday-too/).

St. Jerome in his Chronicon/Chronicle contends that Lucretius “was driven mad by a love potion, and when, during the intervals of his insanity, he had written a number of books, which were later emended by Cicero, he killed himself by his own hand in the 44th year of his life.” This piece of nugget appears only in St. Jerome. It seems unlikely that a man who appears to have felt disdain for passionate love would have forsaken his beliefs and imbibed an aphrodisiac. An interesting early theory by L.P. Wilkinson suggested that Lucretius may have been confused with Lucullus. who supposedly did die after taking a love potion (CR 63 (1949): 47-48). Furthermore, as an Epicure it is doubtful that he would have been inclined to commit suicide. The Epicureans taught that in order to attain joy and pleasure and freedom from fear and bodily pain and tranquility of mind, moderation in desire of all things (romance, food, drink, emotions, etc.) was necessary as well as knowledge of the world, thoughts found already in Plato. Just like the many fantastic stories about Sappho’s alleged jump off of a cliff for a teenage boy, Phaon, were based on the works of comedy writers, Lucretius may also have been the butt of jokes if we are to attribute his death to love sickness.

In Book III (79-82) Lucretius refers to suicide:

“…intereunt partim statuarum et nominis ergo.et saepe usque adeo, mortis formidine, vitae percipit humanos odium lucisque videndae,ut sibi consciscant maerenti pectore letumobliti fontem curarum hunc esse timorem“

“…some wear out their lives for the sake of a statue and a name. And often it goes so far, that for fear of death men are seized by hatred of life and of seeing the light, so that with sorrowing heart they devise their own death, forgetting that this fear is the fountain of their cares…”

In spite of the Epicurean belief in the dissipation of the atoms of the soul at death and in line with the many contradictions in the DRN, Lucretius seems at least on some level to have embraced the idea of reincarnation or at least recycling (there is no life without death):

“haud igitur penitus pereunt quaecumque videntur,quando alid ex alio reficit natura, nec ullamrem gigni patitur nisi morte adiuta aliena” (1.262-264)

“…no visible object utterly passes away since nature makes up again one thing from another, and does not permit anything to be born unless aided by another’s death.”

Lucretius often applies common sense and keen observation in his discussions; for example, when rejecting hybrid creatures claiming that a fire breathing Chimaera would have been an absurdity since her different parts — lion, goat, and serpent — would all have perished by fire (5.901-906).

Optimism and love of nature and of life itself and even of humanity are themes in Book I.

“at nitidae surgunt fruges ramique virescunt arboribus, crescunt ipsae fetuque gravantur; hinc alitur porro nostrum genus atque ferarum” (1.352-354).

…the branches upon the trees grow green, the trees also grow and become heavy with fruit; hence comes nourishment again for our kind and for the wild beasts.”

However, all that changes by the time we get to Book V.

“casas postquam ac pellis ignemque pararunt, et mulier coniuncta viro concessit in unum. . . . . . .cognita sunt, prolemque ex se videre creatam, tum genus humanum primum mollescere coepit” (5.1011-1015)

“When they had gotten themselves huts and skins and fire, and woman mated with man moved into one (home and marriage) became known … then first the human race began to grow soft”

Although Lucretius seems to have felt compassion towards animals (to read Lucretius moving story of a mother cow who is searching for her baby calf that has been taken away from her to be killed at the altar, see the previous blog “Happy Valentine’s Day” https://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/liblog/2018/03/greeks-and-romans-happy-valentine/) equating humans with animals, he also refers to ‘dumb animals” a kind of trope, I guess, although stupidity for Lucretius could be said to be a characteristic also of the human animal species. For women Lucretius expresses less appreciation in spite of the fact that he invokes Venus rather than Jupiter in claiming that

“nam longe praestat in arte et sollertius est multo genus omne virile” (5.1356)

“men are far superior to women in skill and more clever”

in a passage in which Lucretius argues that weaving once used to be the prerogative of men until farmers began to tease them and subsequently the art of weaving was left to women, presumably to the detriment of the craft considering the alleged inferiority of the female sex.

In the following passage Lucretius expresses appreciation for a woman who although may not be physically attractive could still be bearable if she is obliging, neat and clean.

“nam facit ipsa suis interdum femina factis morigerisque modis et munde corpore culto, ut facile insuescat te secum degere vitam. quod superest, consuetudo concinnat amorem; nam leviter quamvis quod crebro tunditur ictu, vincitur in longo spatio tamen atque labascit” (4.1280-1285).

“For a woman sometimes so manages herself by her own conduct, by obliging manners and bodily neatness and cleanliness, that she easily accustoms you to live with her. Moreover, it is habit that breeds love; for that which is frequently struck by a blow, however light, still yields in the long run and is ready to fall.”

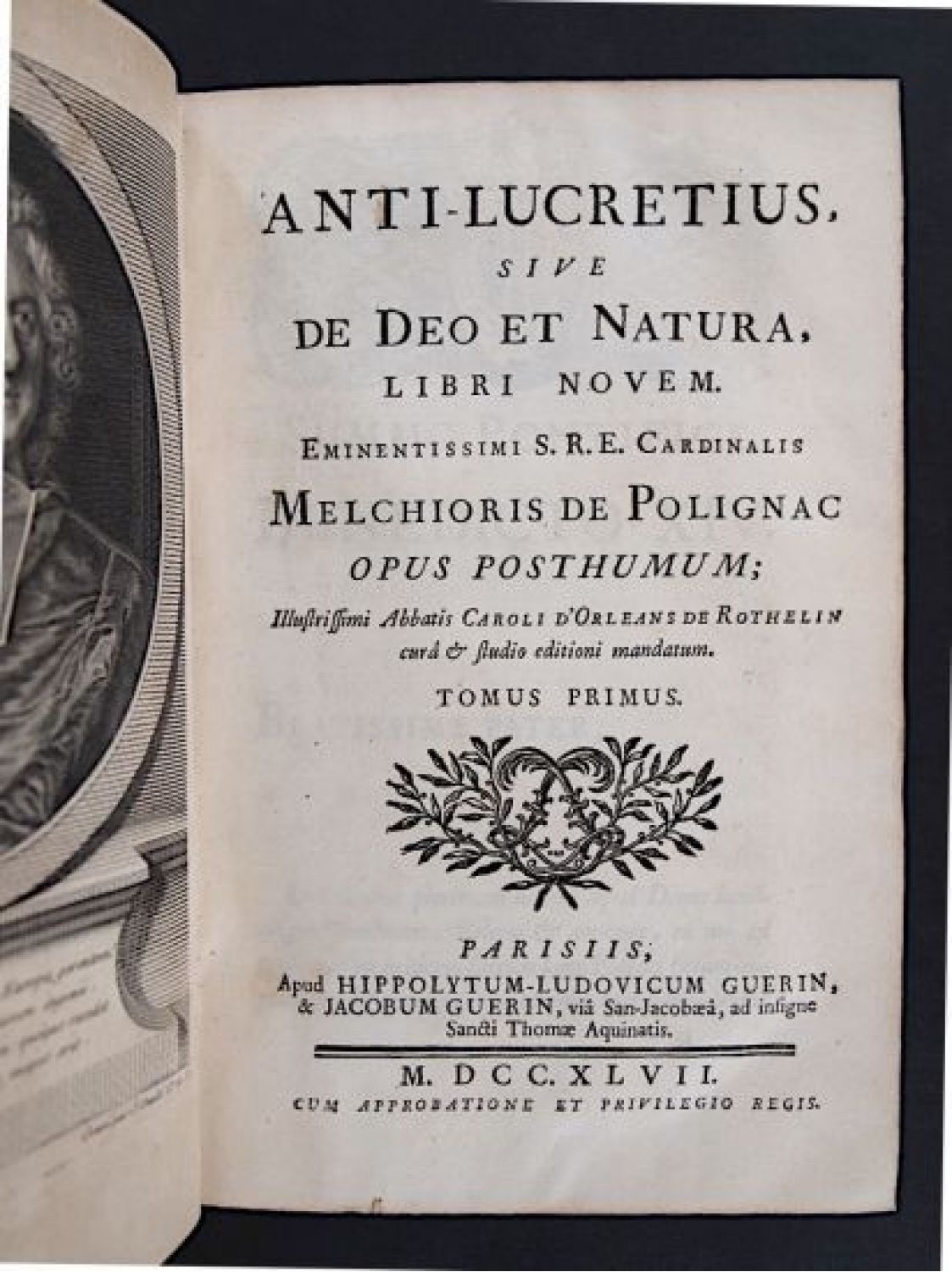

De rerum natura was studied by late antique grammarians such as Servius and Macrobius. Archbishop and scholar Isidore of Seville uses Lucretius passages in his Etymologiae and in his De rerum natura (named after Lucretius’ poem) to explain rerum naturam. However, Lucretius’ poem was seldom read in the Middle Ages, in part because of the perceived anti-religious position of Epicurean philosophy. Even though Lucretius’ poem was rediscovered and became influential during the humanist development of the Renaissance, cardinal Melchior de Polignac wrote as late as in 1747 a poem in Latin in nine books called Anti-Lucretius, sive de Deo et Natura which became very popular and was translated into several languages.

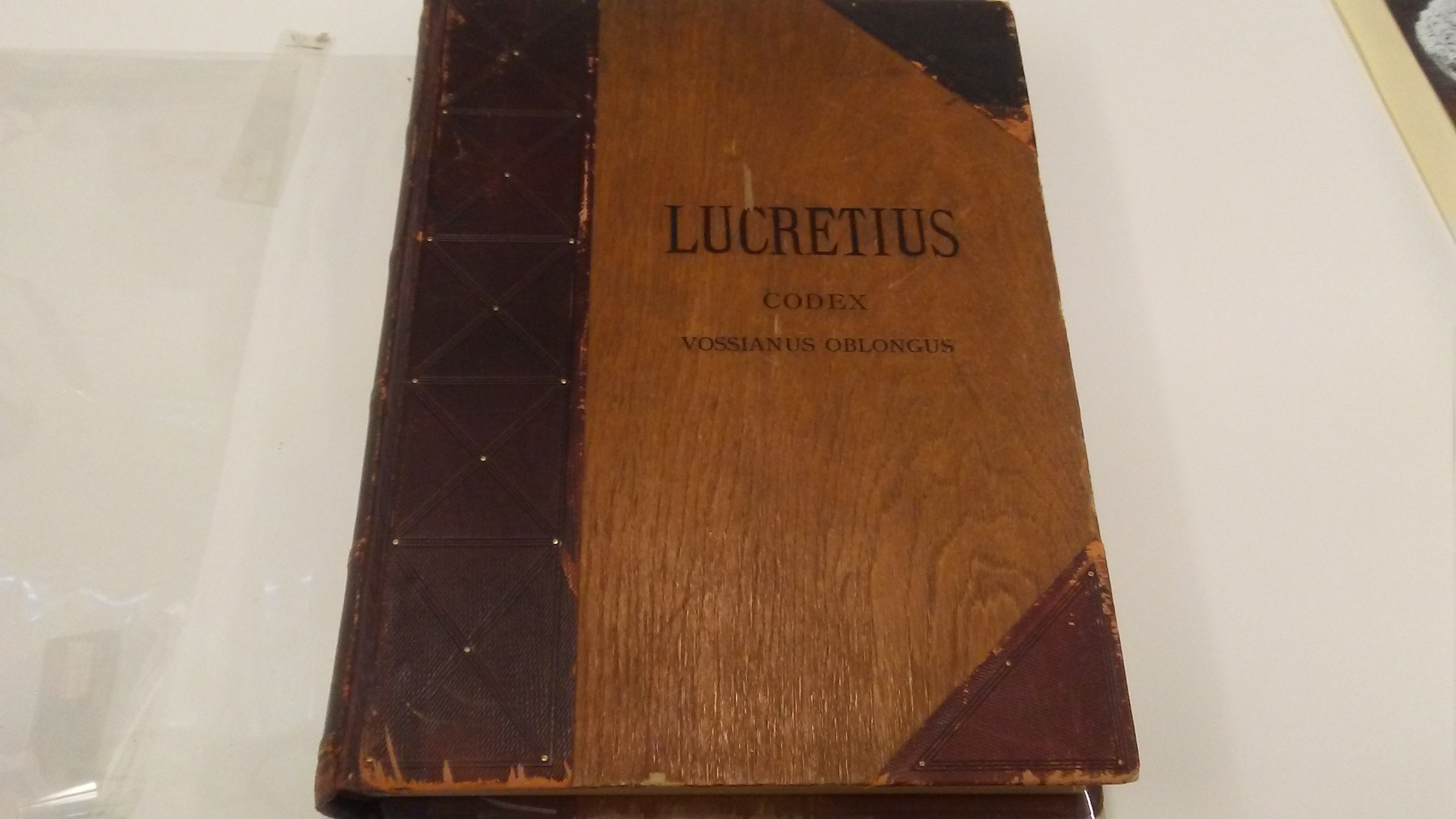

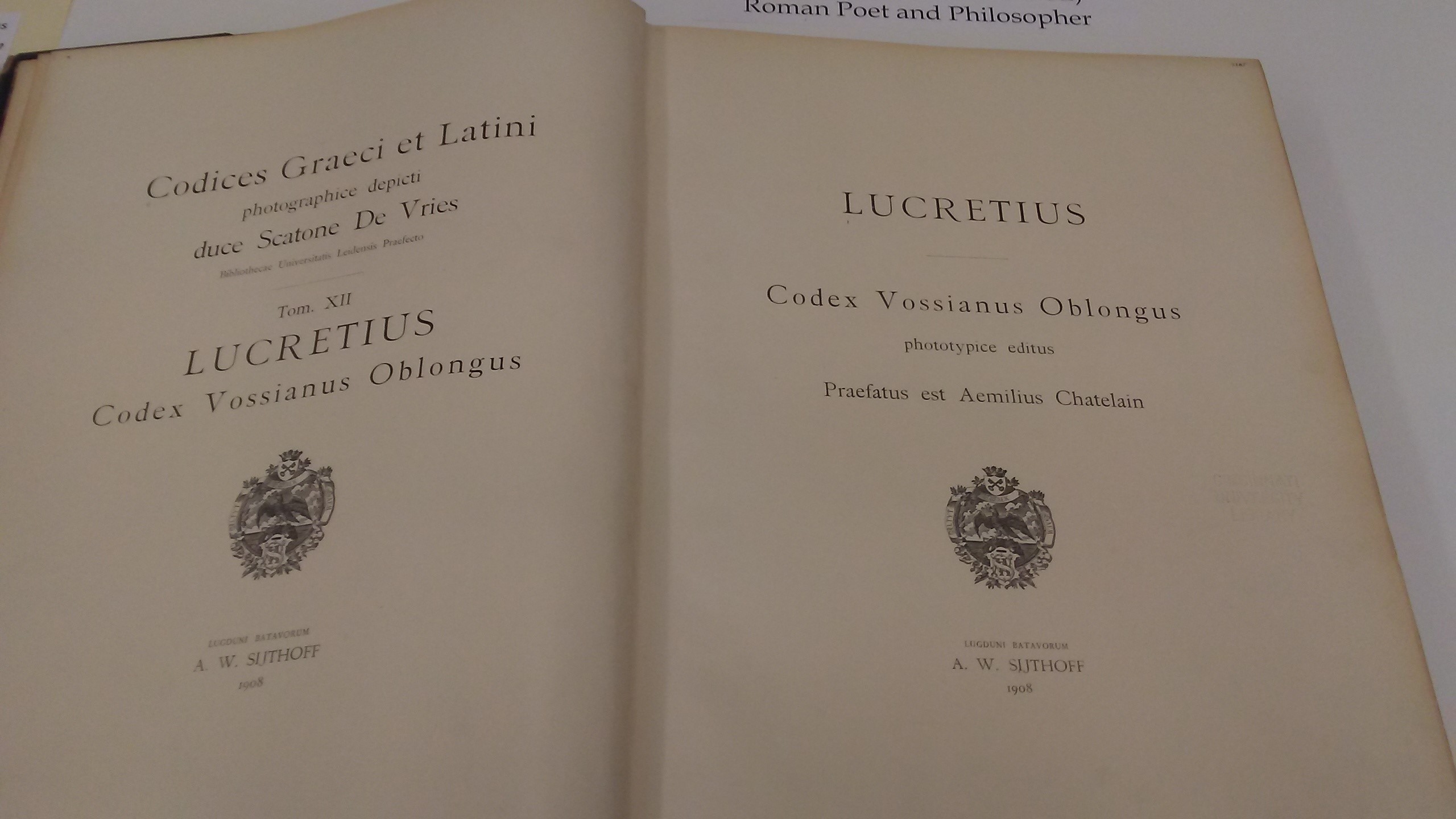

Nevertheless, two important manuscripts do survive from the ninth century, both owned by seventeenth-century Dutch classicist Isaac Vossius and purchased from his estate by the Leiden University Library in 1689. The formats of the two manuscripts have given them their modern designations; the “Oblongus” and the “Quadratus.” The earlier of the two, the Leiden Voss. Lat. Fol. 30, the Oblongus, the facsimile currently on display in the Circulation area of the Classics Library, has an ownership inscription dated 1479 from the cathedral library of St. Martin’s, Mainz. It is a manuscript of 192 leaves measuring c. 314 x 204 mm, with twenty lines per page, and copied in a large early Caroline miniscule. There are frequent contemporaneous corrections and emendations by a corrector, traditionally known as Saxonicus. The corrector has since been identified with an Irish scholar, Dungal, at Charlemagne’s court. The scribe of the Oblongus took pains to produce a legible text which involved careful collaboration with the corrector of the manuscript. The scribe left gaps at line ends for words which he was unable to decipher and omitted some lines, leaving space for Dungal to emend them.

In the early Renaissance De rerum natura was rediscovered in a Benedictine library at Fulda in Germany by Italian humanist scholar Poggio Bracciolini (for more on him see an earlier blog on the Fall of Constantinople https://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/liblog/2018/05/on-may-29-the-classics-library-remembers-the-fall-of-constantinople-and-the-byzantine-empire/). The text of the original manuscript, a copy of which is now housed in the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence, influenced such divergent thinkers as Giordano Bruno, Thomas More, and Michel de Montaigne.

The teachings of Epicurus are still practiced by some. The following are the tenets of modern Epicureanism, at least according to a blog of something that curiously enough calls itself “the Church of Epicurus”:

1) Don’t fear God.

2) Don’t worry about death.

3) Don’t fear pain.

4) Live simply.

5) Pursue pleasure wisely.

6) Make friends and be a good friend.

7) Be honest in your business and private life.

8) Avoid fame and political ambition.

Sounds simple enough. Would Lucretius have approved? ![]()

Select bibliography

Bailey, Cyril. De rervm natvra libri sex; edited with prolegomena, critical apparatus, translation, and commentary. 3 vols. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1947. CLASS Stacks PA6482 .A2 1947

Gale, Monica, R., ed. 2007. Lucretius. Oxford Readings in Classical Studies. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. CLASS Reserves PA6484 .L85 2007

Gillespie, Stuart, and Philip Hardie, eds. 2007. The Cambridge companion to Lucretius. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. CLASS Stacks PA6484 .C33 2007

Hardie, Philip. 2009. Lucretian receptions: History, the sublime, knowledge. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. CLASS Stacks PA6029.P45 H37 2009

Sharrock, Alison. 2006. The philosopher and the mother cow: Towards a gendered reading of Lucretius’ De rerum natura. In Laughing with Medusa: Classical myth and feminist thought. Edited by V. Zajko and M. Leonard, 253–274. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. CLASS Stacks PN56.M95 L38 2006

Warren, James, ed. 2009. The Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. CLASS Stacks B512 .C35 2009

English translation

Lucretius (Titus Lucretius Carus). 2007. The nature of things. Translated by A. E. Stallings, with introduction by Richard Jenkyns. London: Penguin. CLASS Stacks PA6483.E5 S73 2007

Poem online

Loeb Classical Library (UC access only)

Perseus Digital Library (Latin)

Perseus Digital Library (English)