By: Savannah Gulick, Archives & Rare Books Library Student Assistant

Celtic lore has always been fascinating to me and to readers worldwide, but oftentimes it is overlooked by Greek and Roman mythology so I thought I would highlight a few of the tales that exemplify Irish mythology and that are part of our holdings in the Archives & Rare Books Library.

Celtic lore has always been fascinating to me and to readers worldwide, but oftentimes it is overlooked by Greek and Roman mythology so I thought I would highlight a few of the tales that exemplify Irish mythology and that are part of our holdings in the Archives & Rare Books Library.

Celtic Irish society revolved around the cult of warrior heroes. The most important people in early Irish society, equal even to the kings, were the Seanachie or storytellers. A major part of these bards’ duties was to compose poems in praise of the daring deeds of kings and warriors; hence they were held in high esteem in a warrior society.

Irish fairytales often fall into four categories: ancient warrior myths, romances, ghost stories, and local tales of supernatural beings. From the beginning of Celtic society, fairy tales were told through the traditional method of oral storytelling. This led to variations of the same tale throughout different parts of the island, and like all cultures steeped in oral storytelling, characters and story line interlinked and blended throughout history as the culture adapted to social changes in the country. An interesting example of how characters could become confused with each other is the case of the Celtic goddess Aine and the early Christian Saint Brigit. Aine was associated with fire and was credited with acting as an inspiring muse to poets. Saint Brigit was an early Irish Christian who founded a convent in Kildare but popular legend associates her with fire – there was a sacred fire reputedly kept burning at her convent from her death in 525 AD until the  Dissolution of the Monasteries by the English invaders in the 1500s, and she is also considered to be the patron saint of poets. This mixing of native Irish stories and culture with historical Christian figures helps to illustrate how Irish fairy tales survived until the present day. In fact, despite their heretical nature, the earliest Irish myths and fairy tales were written down by Irish monks. From the eighth century on, monks felt secure enough in their Christianity to value fairy tales as an interesting historical legacy rather than as a threat to Christian doctrine.

Dissolution of the Monasteries by the English invaders in the 1500s, and she is also considered to be the patron saint of poets. This mixing of native Irish stories and culture with historical Christian figures helps to illustrate how Irish fairy tales survived until the present day. In fact, despite their heretical nature, the earliest Irish myths and fairy tales were written down by Irish monks. From the eighth century on, monks felt secure enough in their Christianity to value fairy tales as an interesting historical legacy rather than as a threat to Christian doctrine.

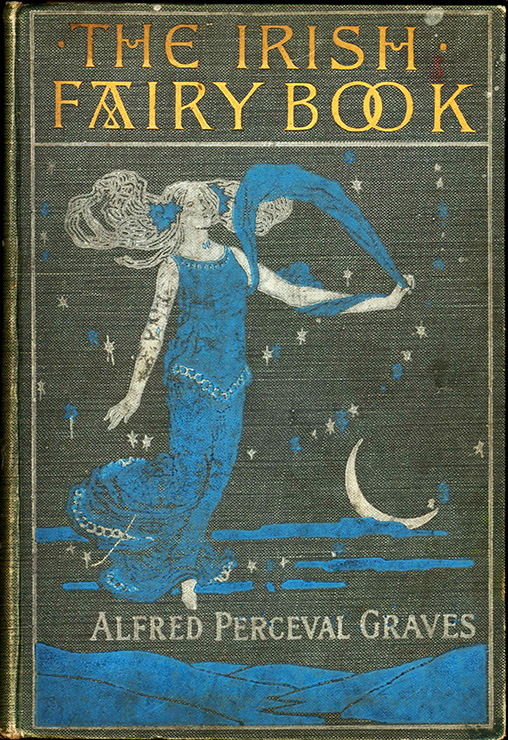

In 1919, Alfred Perceval Graves with the help of his colleagues Dr. Douglas Hyde and Dr. Patrick Weston Joyce, and other collectors, created a compilation of Irish fairy tales, The Irish Fairy Book (call no. SpecCol RB GR153.5.G73 1919). These tales included oral stories written for the first time, poetry, and short stories with illustrations by George Denham. Unfortunately, before the book was published, Dr. Joyce and two of the writers died. This collection encompasses the four categories mentioned above as it ranges from comedies (such as the mad pudding) to horror tales (the horned witches), and featuring princes and nobles as well as laymen and common folk. Altogether they contain that strange blend of old pagan stories mingled with the tenets of Christianity in which the likes of St. Peter and a cast of angels and demons rub shoulders with ancient Irish folk heroes (Finn MacCoul, Cuchulain, Oisin, and King Fergus of Ulster) along with fairies that inhabit that strange place between nature and hell, the old ways and the new religion. The stories contain what you would expect from fairy tales: impossible feats, magical fish, threefold trials, brave princes, wise simpletons, talking animals, fairy revelries, and at least one dragon, all with a distinctly Irish flavor. There are leprechauns and pookas, visits to Tir Na Nog (the Land of Youth), and mentions of specific places in the Irish landscape such as Dublin, Enniscorthy, Aherlow, Cullamore and Loch Lein.

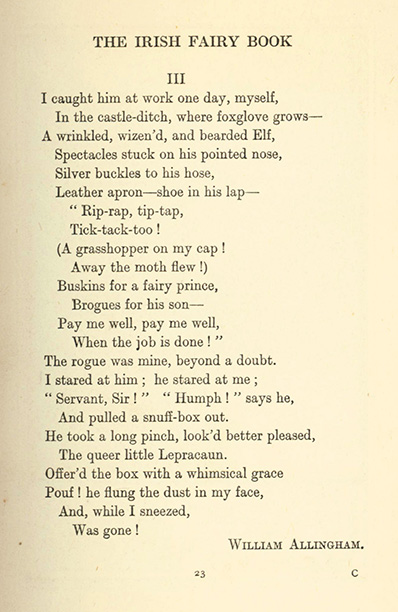

From the thirty-three in the collection, I chose four to highlight. The first is Leprecaun or Fairy Shoemaker by William Allingham. poet William Butler Yeats provided a brief history of leprechauns:

“The name Lepracaun,” Mr. Douglas Hyde writes to me, “is from the Irish leith brog–i.e., the One-shoemaker, since he is generally seen working at a single shoe. It is spelt in Irish leith bhrogan, or leith phrogan, and is in some places pronounced Luchryman, as O’Kearney writes it in that very rare book, the Feis Tigh Chonain.”

“The name Lepracaun,” Mr. Douglas Hyde writes to me, “is from the Irish leith brog–i.e., the One-shoemaker, since he is generally seen working at a single shoe. It is spelt in Irish leith bhrogan, or leith phrogan, and is in some places pronounced Luchryman, as O’Kearney writes it in that very rare book, the Feis Tigh Chonain.”

“The Lepracaun, Cluricaun, and Far Darrig. Are these one spirit in different moods and shapes? Hardly two Irish writers are agreed. In many things these three fairies, if three, resemble each other. They are withered, old, and solitary, in every way unlike the sociable spirits of the first sections. They dress with all unfairy homeliness, and are, indeed, most sluttish, slouching, jeering, mischievous phantoms. They are the great practical jokers among the good people. The Lepracaun makes shoes continually, and has grown very rich. Many treasure-crocks, buried of old in wartime, has he now for his own. In the early part of this century, according to Croker, in a newspaper office in Tipperary, they used to show a little shoe forgotten by a Lepracaun” (W.B. Yeats, 1919).

Included here is an image of the third part of the poem. Trivia aside, this poem has a nice musicality to it and illustrates the trickster or impish side of leprechauns.

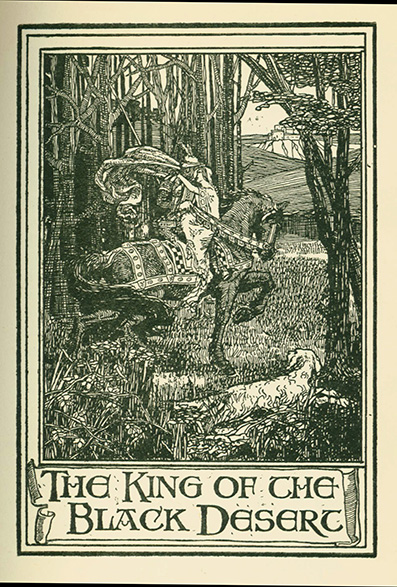

The second story is The King of the Black Desert by Dr. Hyde. From the introduction in the book: “This story was told by one Laurence O’Flynn from near Swinford, in the County Mayo, to my friend, the late F. O’Connor, of Athlone, from whom I got it in Irish. It is the eleventh story in the “Sgeuluidhe Gaodhalach” and is here for the first time literally translated into English” – An Chraoibhin Aoibhinn. The story tells the tale of King O’Conor’s son and his dealings with an enchanter. The son happens upon the old man one day and requests two tasks after he beats the old man in cards: turn his stepmother’s head into a goat head and fill the castle’s pasture with cows. On the third journey to the old man, the son loses in playing ball (hurling, perhaps?) and has to locate the old man’s castle before a year’s time or he will die. With the help of magical beings, the son locates the castle and accomplishes the tasks set before him, ultimately winning the marriage of one of the old man’s daughters (at this point, you learn the old man is the King of the Black Desert). The picture here is of the son and the daughter riding back to his castle. I chose this story because it highlights different magical beings and was originally an oral tale until Hyde wrote it down.

The second story is The King of the Black Desert by Dr. Hyde. From the introduction in the book: “This story was told by one Laurence O’Flynn from near Swinford, in the County Mayo, to my friend, the late F. O’Connor, of Athlone, from whom I got it in Irish. It is the eleventh story in the “Sgeuluidhe Gaodhalach” and is here for the first time literally translated into English” – An Chraoibhin Aoibhinn. The story tells the tale of King O’Conor’s son and his dealings with an enchanter. The son happens upon the old man one day and requests two tasks after he beats the old man in cards: turn his stepmother’s head into a goat head and fill the castle’s pasture with cows. On the third journey to the old man, the son loses in playing ball (hurling, perhaps?) and has to locate the old man’s castle before a year’s time or he will die. With the help of magical beings, the son locates the castle and accomplishes the tasks set before him, ultimately winning the marriage of one of the old man’s daughters (at this point, you learn the old man is the King of the Black Desert). The picture here is of the son and the daughter riding back to his castle. I chose this story because it highlights different magical beings and was originally an oral tale until Hyde wrote it down.

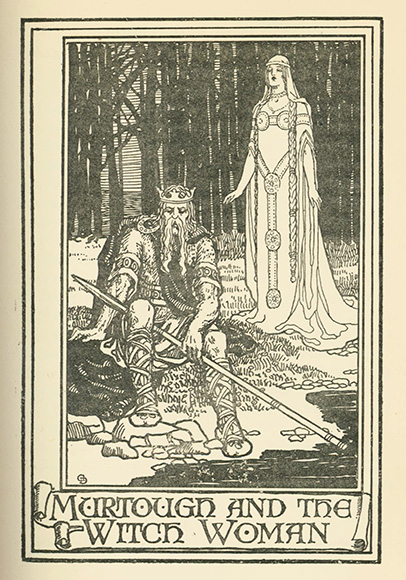

The third story is Murtough and the Witch Woman by Eleanor Hull. This story occurs during the conversion of Ireland from paganism to Christianity.  The king, Murtough, has steadfastly remained a pagan while the rest of his family and kingdom have accepted Christianity. One day a beautiful woman – “Sigh”, “Sough”, “Storm”, “Rough Wind”, “Winter Night”, “Cry”, “Wail”, “Groan” but men called her “Sheen” – approaches the king and convinces him to turn out his family and people for her. The picture from this story is when Sheen approaches the king while they are in the woods and he notices her ethereal beauty. Sheen despises the king because in the battle where the fairy people fought the king’s people, Sheen lost her mother, father, and sister as well as many fellow fairies. Once she has him under her spell, which she can only do because he is not a supporter of Christianity, she kills the king for revenge even though she is in love with him. Murtough’s wife accidentally kills herself by leaning against an enchanted tree. While they are being buried together, Sheen appears, kills herself over her grief of killing the king but admits that she had to do so in order to revenge the death of her people. I really enjoyed reading this particular tale as it highlights an important time in the country’s history when Christianity invaded.

The king, Murtough, has steadfastly remained a pagan while the rest of his family and kingdom have accepted Christianity. One day a beautiful woman – “Sigh”, “Sough”, “Storm”, “Rough Wind”, “Winter Night”, “Cry”, “Wail”, “Groan” but men called her “Sheen” – approaches the king and convinces him to turn out his family and people for her. The picture from this story is when Sheen approaches the king while they are in the woods and he notices her ethereal beauty. Sheen despises the king because in the battle where the fairy people fought the king’s people, Sheen lost her mother, father, and sister as well as many fellow fairies. Once she has him under her spell, which she can only do because he is not a supporter of Christianity, she kills the king for revenge even though she is in love with him. Murtough’s wife accidentally kills herself by leaning against an enchanted tree. While they are being buried together, Sheen appears, kills herself over her grief of killing the king but admits that she had to do so in order to revenge the death of her people. I really enjoyed reading this particular tale as it highlights an important time in the country’s history when Christianity invaded.

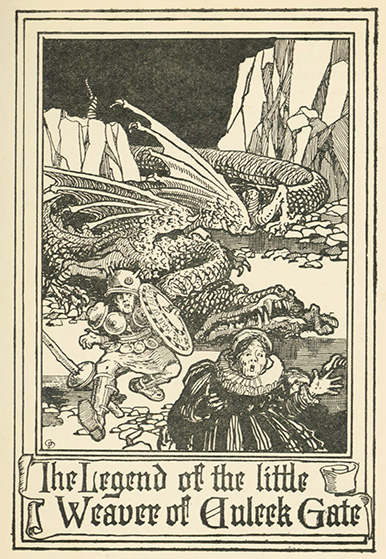

Finally, the fourth story is The Legend of the Little Weaver of Duleek Gate by Samuel Lover. The tale is noted for being about chivalry. One of the main reasons I selected this tale is because the spelling is written in order to convey the dialect: weaver is “waiver”, devil is “divil”, and height is “hoighth”, to  name a few. The inclusion of this is to preserve the Irish accent as the story was originally told orally. The weaver is an honest and industrious man who one day kills thirteen flies with his one fist. This causes the weaver to spiral a bit out of control and declare that he was off to kill the “dhraggin” for the king so he can become a knight “arriant”. Everyone thinks the man a bit foolish but he continues with his quest. Upon his arrival to the kingdom and a nap on the seats below the throne, the king agrees to let him try to slay the dragon. The weaver returns to the castle on top of the dragon which he has tamed – the illustration highlights the weaver in his absurd outfit with the dragon and his future wife. He admits that he could not behead the beast himself but offers the opportunity to the king. Once the dragon is beheaded, the king admits the weaver is no knight but offers him instead the title of Lord Mount Dhraggin as well as his daughter’s hand. The hand in marriage was nothing more than what the king had promised the weaver in the first place because his daughter was the “greatest dhraggin ever was seen, and had the divil’s own tongue, and a beard a yard long”. The comical twist at the end of the story caught me by surprise but made the tale quite farcical.

name a few. The inclusion of this is to preserve the Irish accent as the story was originally told orally. The weaver is an honest and industrious man who one day kills thirteen flies with his one fist. This causes the weaver to spiral a bit out of control and declare that he was off to kill the “dhraggin” for the king so he can become a knight “arriant”. Everyone thinks the man a bit foolish but he continues with his quest. Upon his arrival to the kingdom and a nap on the seats below the throne, the king agrees to let him try to slay the dragon. The weaver returns to the castle on top of the dragon which he has tamed – the illustration highlights the weaver in his absurd outfit with the dragon and his future wife. He admits that he could not behead the beast himself but offers the opportunity to the king. Once the dragon is beheaded, the king admits the weaver is no knight but offers him instead the title of Lord Mount Dhraggin as well as his daughter’s hand. The hand in marriage was nothing more than what the king had promised the weaver in the first place because his daughter was the “greatest dhraggin ever was seen, and had the divil’s own tongue, and a beard a yard long”. The comical twist at the end of the story caught me by surprise but made the tale quite farcical.

For more information about the Irish folklore and fairy tales, visit the Archives & Rare Books Library on the 8th floor of Blegen Library. We are open Monday through Friday, 8:00 am-5:00 pm. You can also call us at 513.556.1959, email us at archives@ucmail.uc.edu, visit us on the web at http://www.libraries.uc.edu/arb.html, or have a look at our Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/ArchivesRareBooksLibraryUniversityOfCincinnati