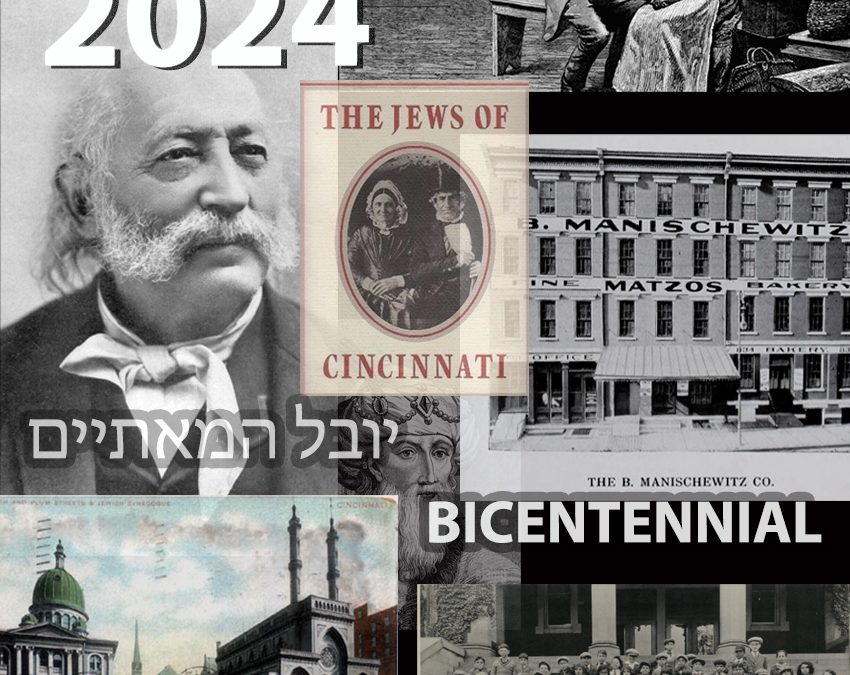

On January 18, 1824, the first Jewish congregation in Cincinnati was formed, the first west of New York, making the Queen City a center of Judaism in the United States.

The first recorded Jewish man in Cincinnati was Joseph Jonas, a watchmaker, from Plymouth in England, who arrived in New York in October 1816 with the intent of making his way to the new city of Cincinnati. He left for Cincinnati from Philadelphia on January 2 in 1817 but did not arrive in Cincinnati until March 8, two months later, after a long and difficult journey traveling in horse carriage across the mountains and then on a flatboat (see below) south on the Ohio River.

After Jonas several other settlers arrived, mostly Jews from England. However, the first formal congregation was not established until 1824, when the number of known Jewish inhabitants had reached about twenty.

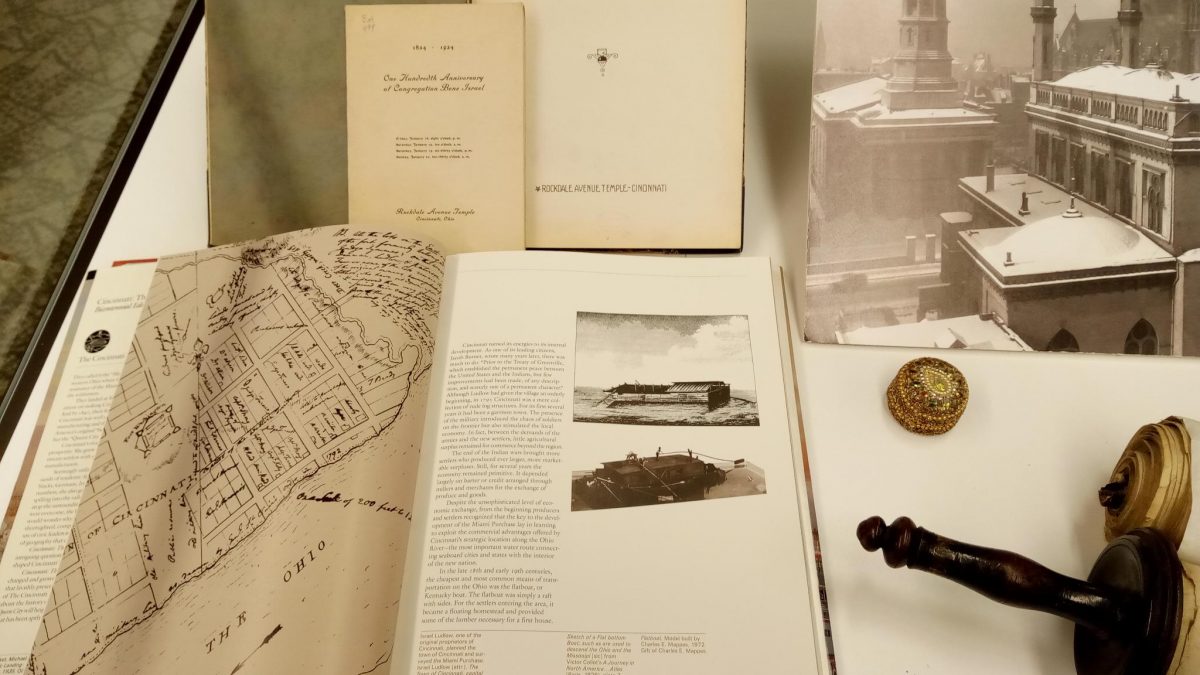

“In accordance with a resolution of a convention which met at the residence of Morris Moses in the city of Cincinnati, State of Ohio, on the fourth of January, 1824, corresponding with the fourth of Shebat, 5584, a full convention of every male of the Jewish persuasion was convened at the house of the aforesaid Morris Moses on the eighteenths of January, 1824, corresponding with the eighteenth day of Shebat, 5584” (One Hundredth Anniversary: 1824-1924, p. 11).

The Congregation B’ne Israel was formally organized on January 18. Initially, the congregation worshiped in rooms in downtown Cincinnati until thanks to financial support mostly from outside of Cincinnati, the congregation was able to purchase a lot on Broadway, between Fifth and Sixth, in 1829. The first synagogue opened on September 9, 1836. On September 19, 1841, the B’nai Yeshurun congregation was organized by German Jews. A third congregation, Adath Israel, was founded in 1847, a fourth, Ahabath Achim in 1848.

The first association of American synagogues, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, was born in Cincinnati in 1873. The first Jewish institute of higher learning in the country, the Hebrew Union College, was established in 1875.

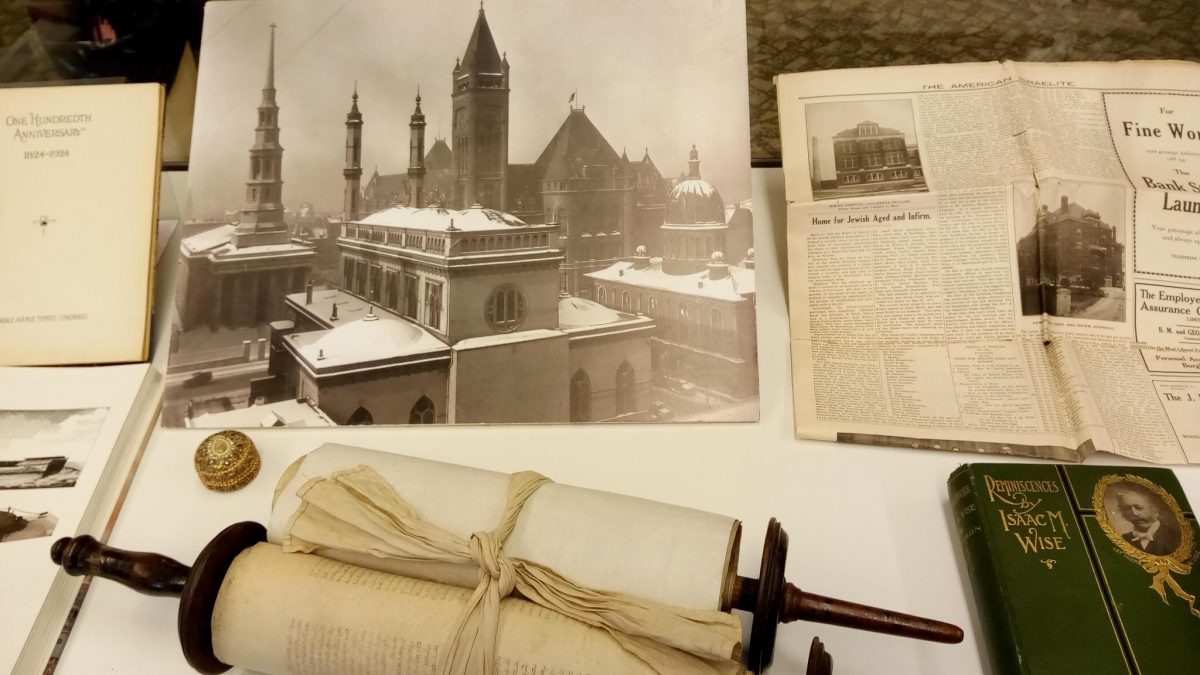

In April 1854, Isaac Mayer Wise became the first rabbi of the B’ne Yeshurun congregation, established after B’ne Israel, by German Jews. Rabbi Isaac M. Mayer was one of the foremost rabbis of his time, a reformer who introduced such radical ideas as counting women to form a minyan (religious quorum); allowing women and men to sit together in family pews; eliminating the Bar Mitzvah which in Wise’s view was meaningless because at that age a boy cannot understand Judaism, and replacing it later with confirmation, open to girls as well; and having mixed-sex choirs. Wise was president of HUC, on the board of directors of UC, and editor of the (American) Israelite (the second oldest American Jewish newspaper in 1854 (see below), and Die Deborah, a German-language supplement for women. Wise was a prolific writer and lectured all over the United States.

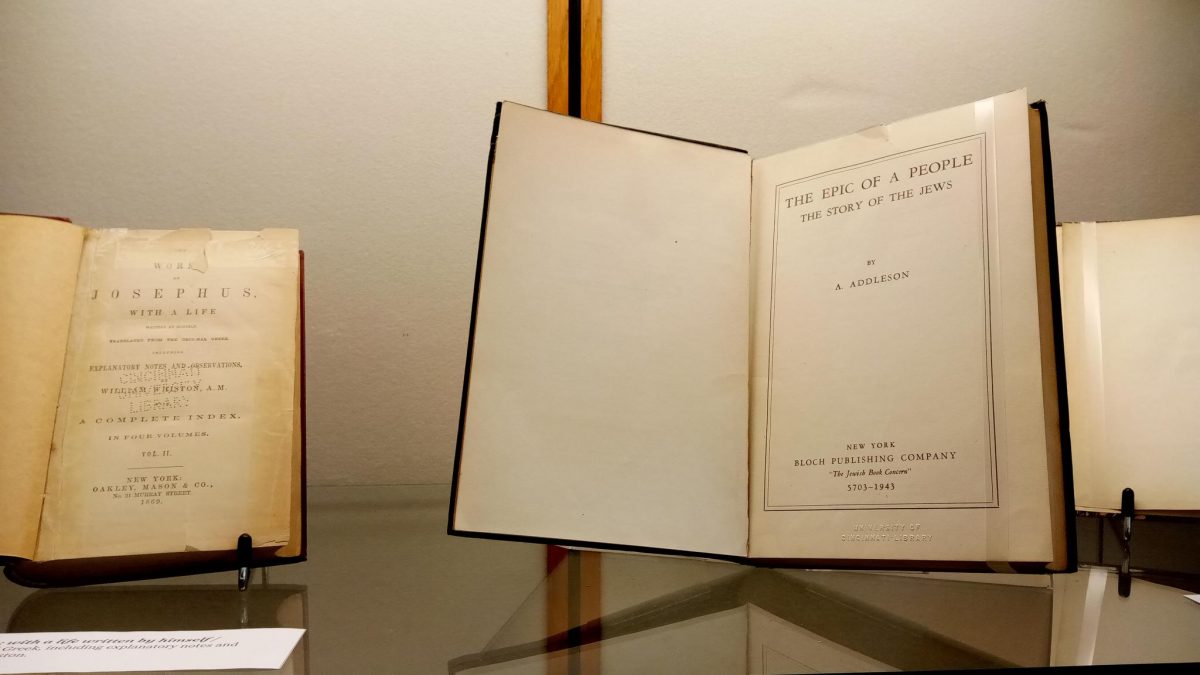

Wise’s brother-in-law, Edward Bloch, founded the largest Jewish publication house in the country, The Bloch Publishing Company (seen below and displayed in the reading room).

In 1866, the congregation built the monumental Plum Street Temple, then named the Isaac M. Wise Temple (seen in a photograph on loan from Elizabeth Meyer, head of the DAAP library). The architect was James Keys Wilson. It is one of only two synagogues in the United States built in a Byzantine-Moorish style. The other one is in New York City.

Reference:

Rabbi David Philipson. The Oldest Jewish Congregation in the West: Bene Israel Cincinnati One Hundredth Anniversary: 1824-1924.

This month we celebrate the bicentennial of the founding of the first Jewish house of worship here in Cincinnati. The materials on exhibit will be available for viewing until February 15, and include both artifacts from the early years of the Jewish community from the special collections of the Klau Library, and the rare books described below from the Burnam collection.

Addendum

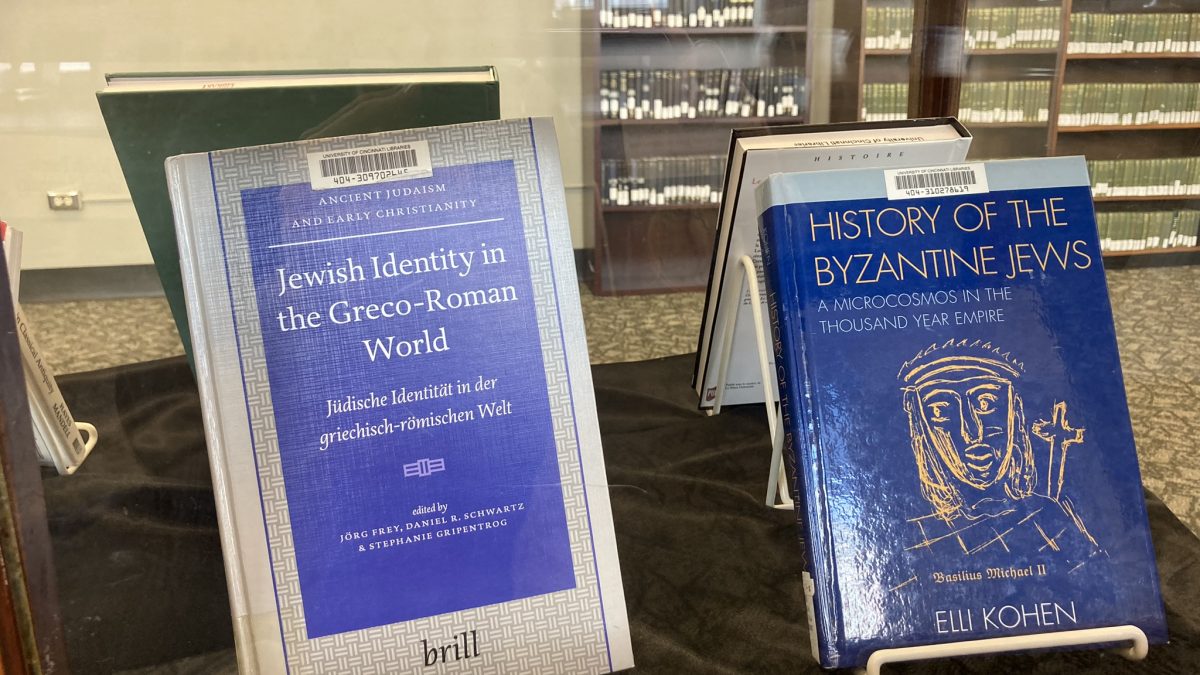

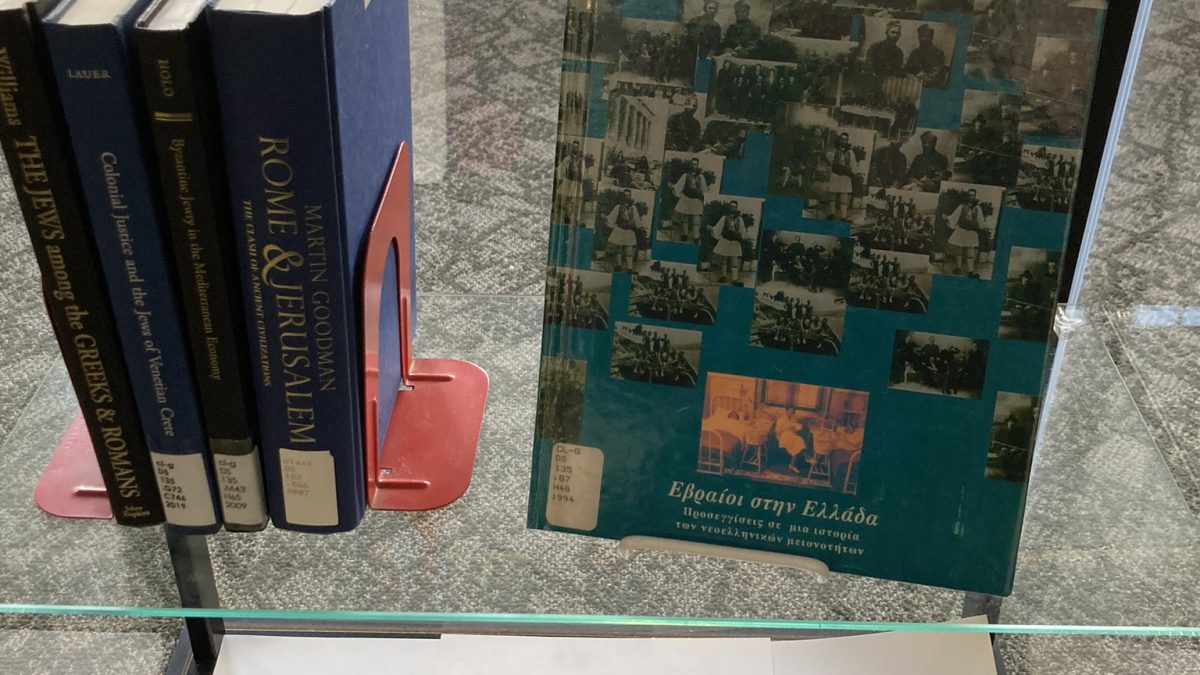

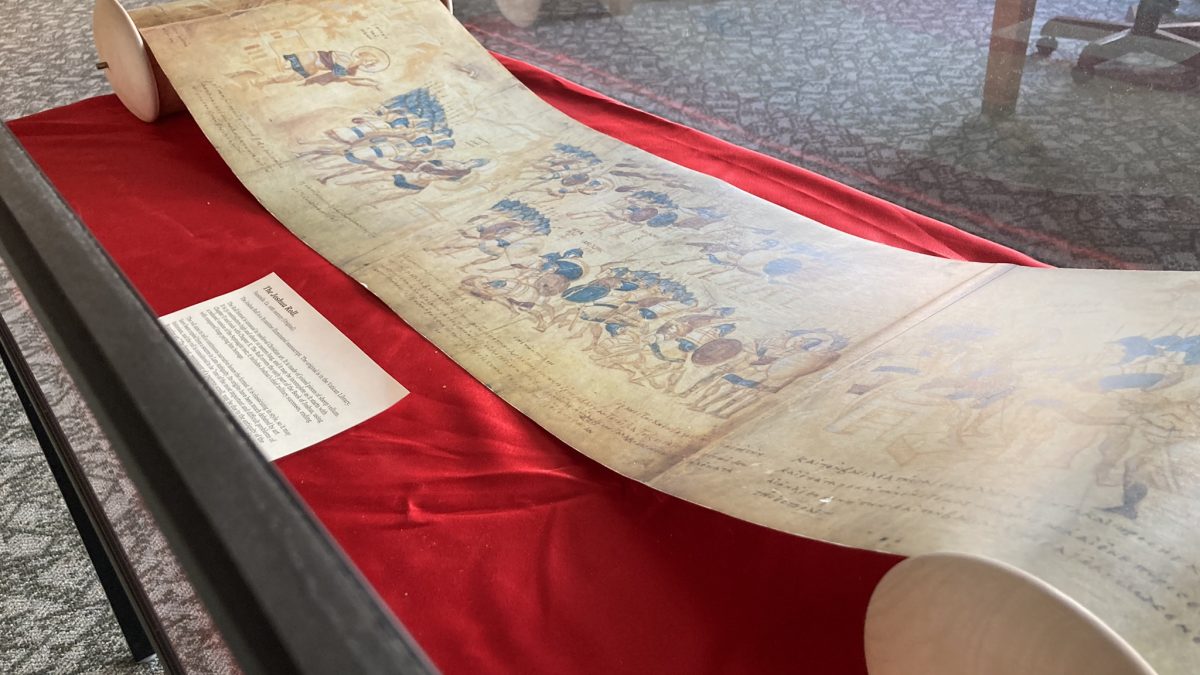

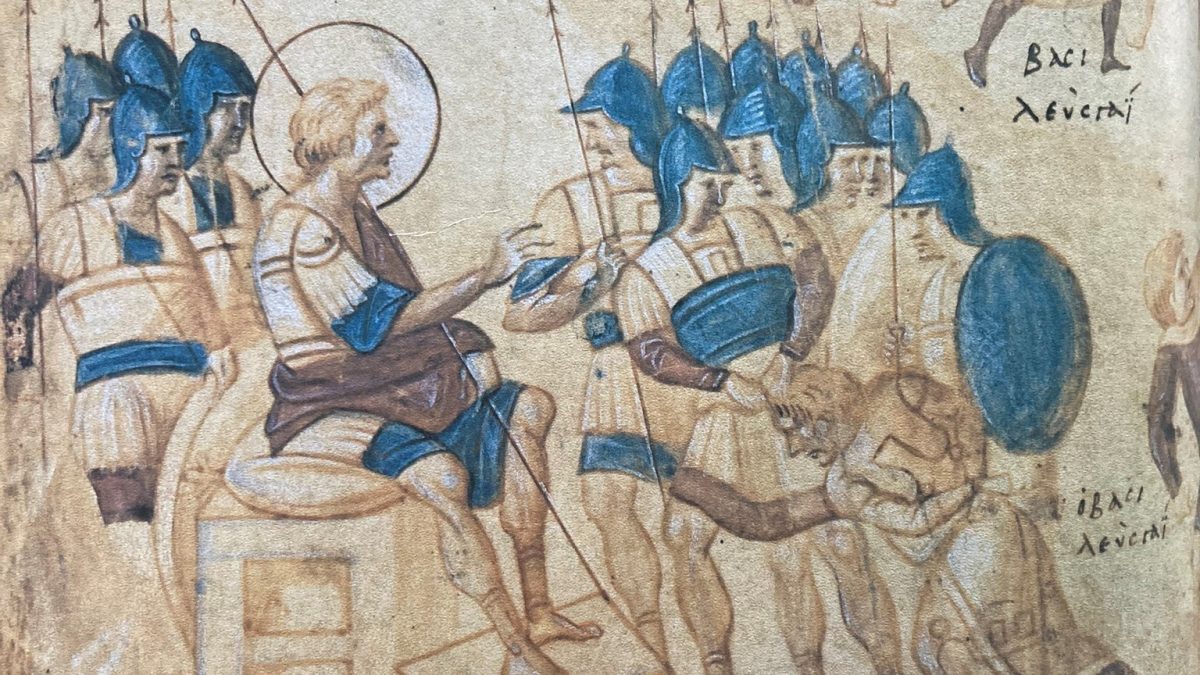

As most of the Burnam collections comprise books about classical antiquity, added to the main Bicentennial Commemoration are also books by and about Jews in antiquity, such as a beautiful facsimile of The Joshua Roll, a Byzantine illuminated manuscript. The original is in the Vatican Library.

The roll (or scroll) format is unusual in Byzantine art. The Roll covers the early part of the Book of Joshua.

The depictions aim to tell a continuous narrative, hence the format works well. The classicizing style points to the possibility of the roll having been copied from a source in Late Antiquity. Its origins have been much debated by art historians. The format, reminiscent of a papyrus scroll, may be explained by respect for the antiquity of the subject, the format of the Torah, an earlier papyrus or parchment scroll, and/or inspired by scroll-like columns in Rome such as those of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius and elsewhere narrating, in continuous strands, battles and conquests by Roman emperors just like Joshua, the son of a king, battled for the Promised Land.

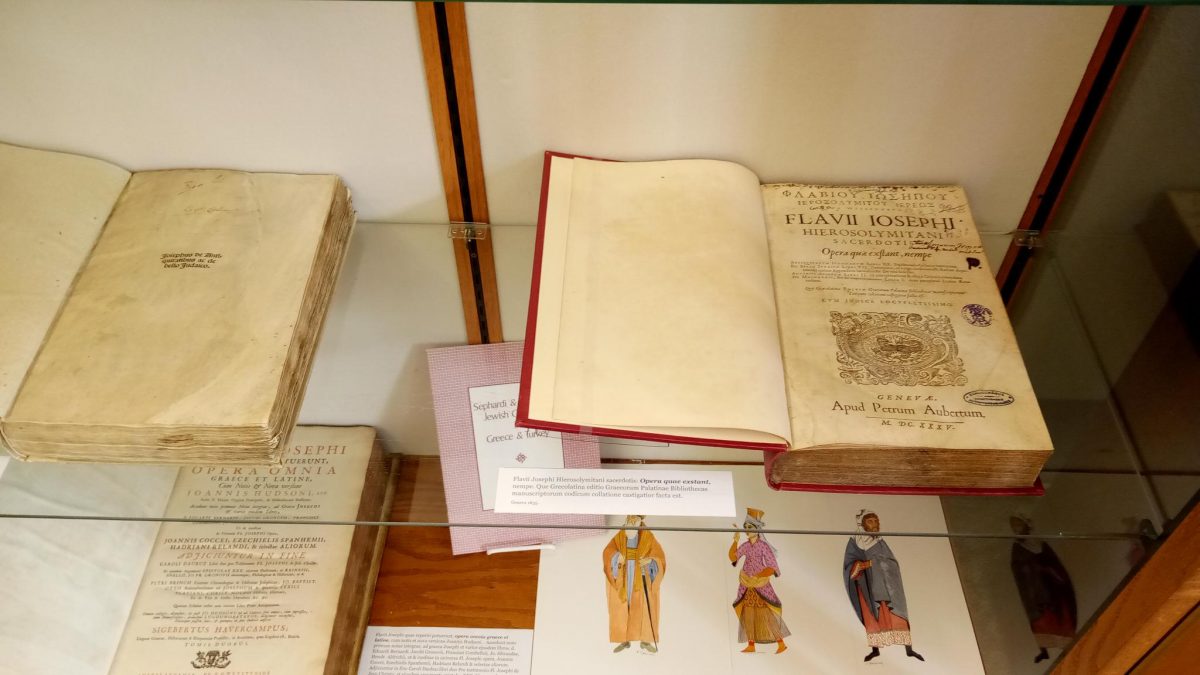

The Classics Library possesses several rare editions, including an incunabulum from 1499, of the works of Josephus (b. 37/38 CE), a Greek (language) Roman (citizenship) historian and Jewish priest of aristocratic background, born in Jerusalem in the Roman province of Judaea. When he was merely in his twenties, Josephus was appointed military governor of Galilee during the First Jewish-Roman War. He negotiated with Emperor Nero for the release of some Jewish priests, and was granted manumission by Emperor Vespasian after he prophesized the emperor’s accession. Suetonius in Vespasian 5.6 writes: “one of the noble captives, Josephus, when he was being thrown into chains, very firmly insisted that he would be released by the same man [Vespasian] soon, but by that time as emperor.” Josephus assumed Emperor Vespasian’s family name of Flavius. He later became a friend and advisor to Emperor Titus serving as a translator when Titus led the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE was granted Roman citizenship, and, after the war, a pension and land.

Josephus most important works are The Jewish (or Judean) War (ca. 75 CE) in seven books and Jewish (or Judean) Antiquities (ca. 94 CE) in twenty books. The Jewish War details the Jewish revolt against Roman occupation; Jewish Antiquities the history of the world from Genesis to 66 CE., the outbreak of the Judean revolt, a period of around 5000 years.

“I have no intention of rivaling those who extol the Roman power by exaggerating the deeds of my compatriots. I will faithfully recount the actions of both combatants, but in my reflections on the events I cannot conceal my private sentiments, nor refuse to give my personal sympathies scope to bewail my country’s misfortunes” (BJ 1.4). I will describe the incidents of the war through which I lived with all the detail and elaborations at my command… (BJ 1.6).

Josephus’ works are the main source for the Jewish high priests in Second Temple Judaism and his writings, based in part on histories of Nicolaus of Damascus and Strabo, provide accounts of Herod (whose tomb was discovered interpreting Josephus’ descriptions of the Galilee and Golan areas), the Pharisees, the Essenes, the Zealots, Pontus Pilate, John the Baptist, and Jesus. Josephus recorded the Great Jewish Revolt (66–70 CE), including the siege of Masada. When describing the fall of Jerusalem, Josephus does not chide away from the horrors of war recounting brutal violence, famine, and cannibalism (Maria’s cannibalism, 6.193–219).

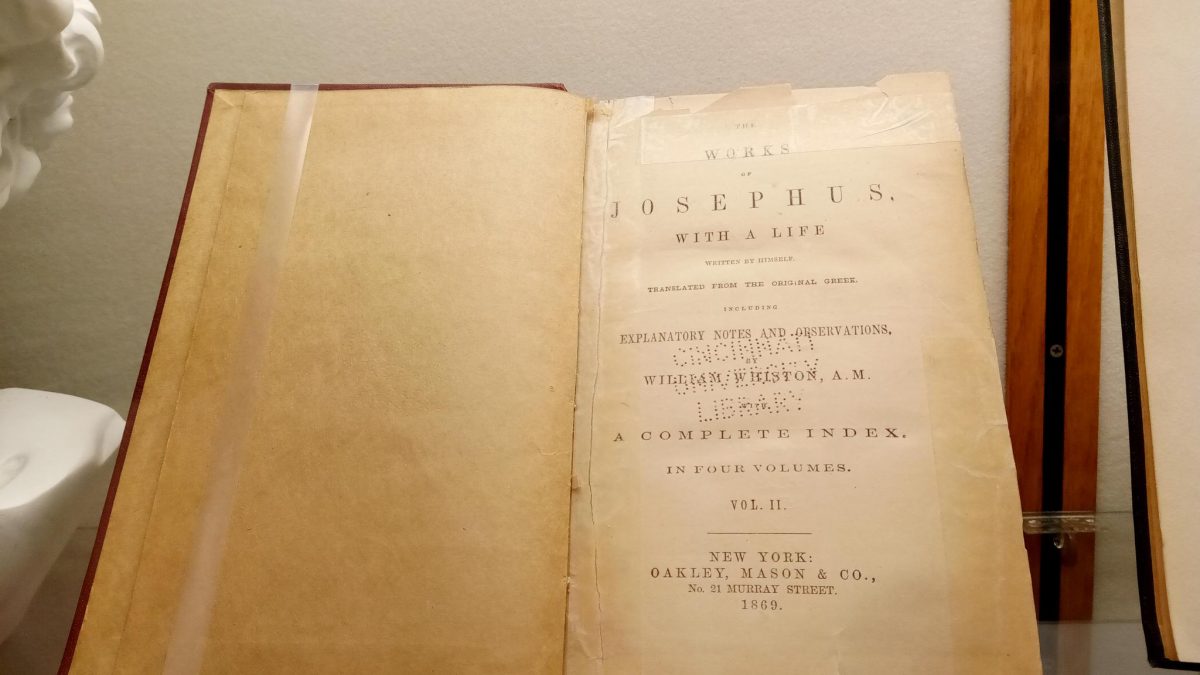

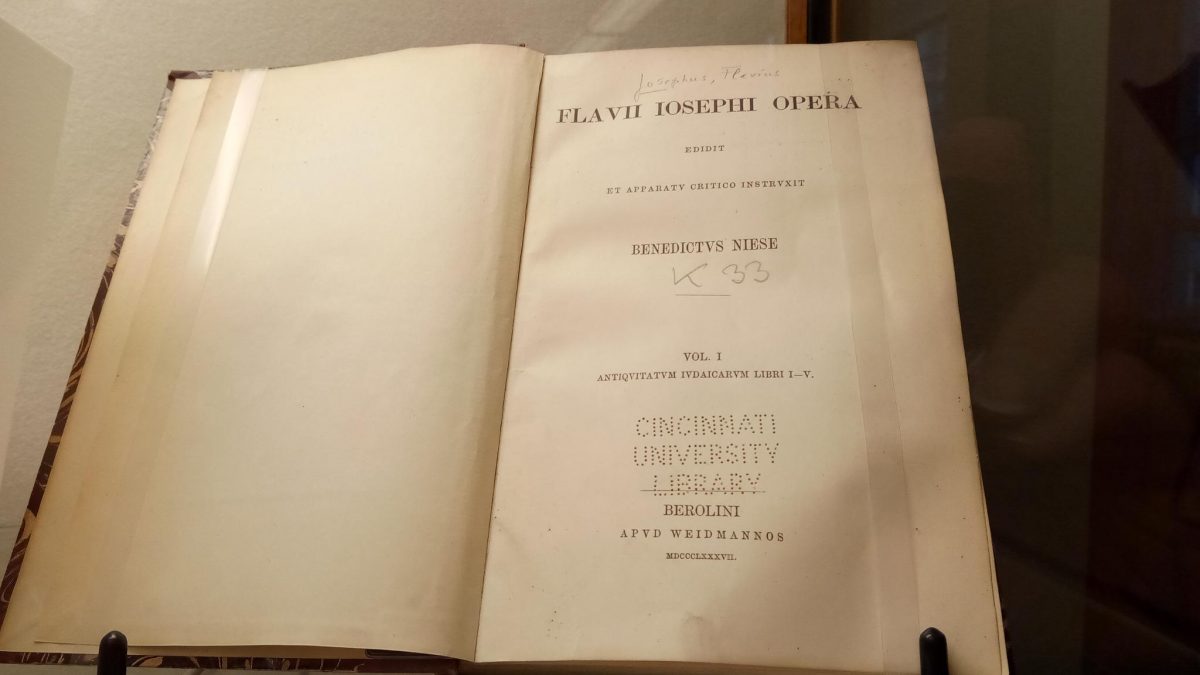

Josephus wrote in Greek although supposedly there was first an Aramaic version, since lost, written for recipients in the Parthian Empire before the Greek version of the Jewish War. In the Middle Ages there was a proliferation of Greek and Latin manuscripts of Josephus’ works, attesting to his popularity. Comparing the popularity of Cassiodorus’ Historia tripartita, and other historical works, James O’Donnell says that Jewish Antiquities was “the single most copied historical work of the middle ages” (O’Donnell 1979, 246). According to Schreckenberg, Josephus’ works were “a kind of fifth gospel” and a “little Bible” (Schreckenberg 1987, 317). The Gutenberg Press led to Josephus’ works being translated into vernacular languages. The first English translation, by Thomas Lodge, appeared in 1602 (not in our collection). In our collection is William Whiston’s English translation from 1732. The classics library’s copy is from 1869 (see below). ARB has an edition from 1777. Kalman Schulman wrote a Hebrew translation of the Greek text of Josephus in 1863. The standard German edition by Benedictus Niese, published in Berlin by Weidmann in 1895, is also featured in the exhibition (see below).

References:

A Companion to Josephus in his World. Honors Howell Chapman and Zuleika Rodgers (eds.). John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

“Josephus” by Edith Mary Smallwood and Tessa Rajak. Oxford Classical Dictionary, fifth ed. 2016.

O’Donnell, James J. Cassiodorus. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

Schreckenberg, Heinz. 1987. “The Works of Josephus and the Early Christian Church.” In Josephus, Judaism, and Christianity. Louis H. Feldman and Gohei Hata (eds.), 315–324. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University, 1987.

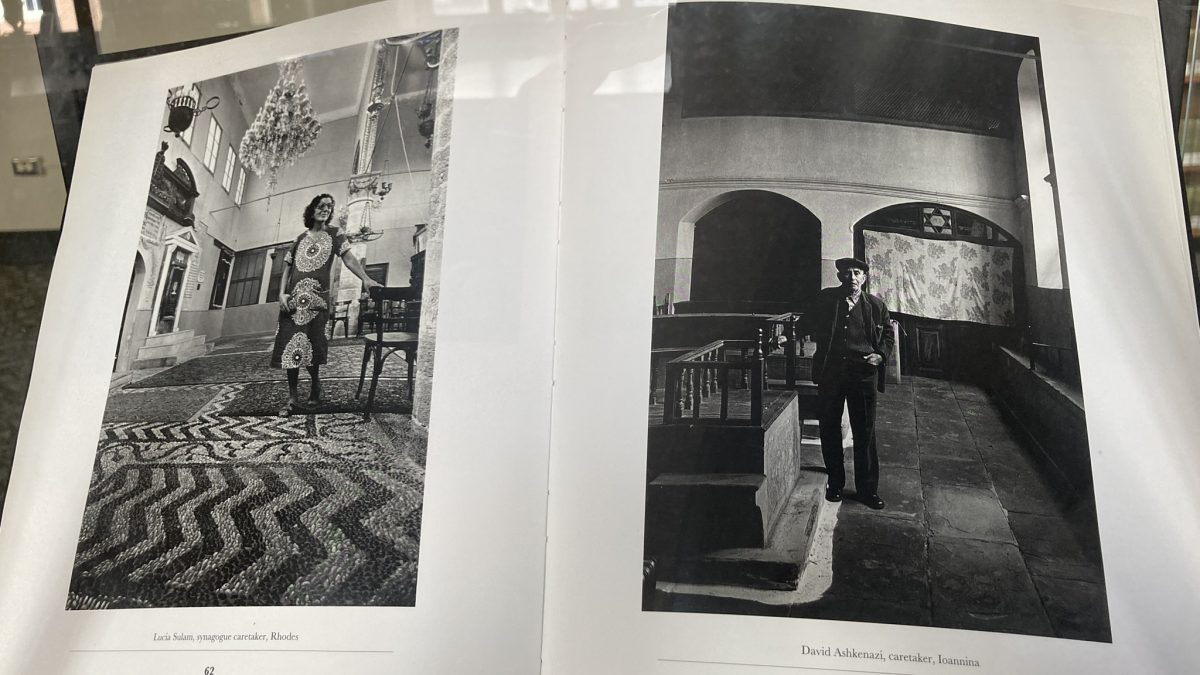

Also included in the exhibition are several works on Jews in antiquity, and picture books with photographs of Jewish individuals from family, working, and religious lives in Greece before WWII, and colorful drawings of historical Jewish folk costumes from Greece and Anatolia.