By Laura Laugle

Cincinnati has had a housing problem for a long time; after all, only so many people can fit into the basin that makes up downtown and its immediate surroundings. However, for much of the city’s early history, the African American population was so small and resident Caucasians depended so heavily on the services which they provided that their housing was simply not a problem. The few blacks living in Cincinnati in 1900 made up only about 4.5% of the city’s total population. Out of practicality (who could afford to rent a horse each day for the housemaid’s commute?) blacks lived either with the white families they served or in neighborhoods close to the whites for whom they worked. As a result, high income white neighborhoods were home to black domestics and middle and lower income white neighborhoods, especially those near business districts, were home to working class blacks. That is not to say that race relations in Cincinnati were A-Ok; there were riots throughout the 1800s, rampant legal and illegal discrimination and general tension, but whites simply had no other choice but to accommodate the blacks living among them.

Real problems began to arise during and following the Great Migration. During this period, from about 1910 through 1940, millions of blacks moved from the extremely oppressive South to the less oppressive North. Cincinnati’s position as “first stop” en route to the North and abundance of industry made it a prime locale for blacks searching for a new and better life. Unfortunately, even though the popularization of the automobile made it possible for many of the city’s more affluent citizens to move out of the basin into the suburbs, Cincinnati’s housing market wasn’t ready for the surge of people. With the sudden removal of high class whites and influx of poor blacks from the South, property values began dropping almost as quickly as tensions rose. White citizens began turning to discriminatory covenants to keep blacks out of their neighborhoods. These covenants were contracts wherein a home owners association or the seller of a property restricted the use of that property. These covenants were often required when buying a home and in this case, restricted the buyer from ever selling to a “non-white.” Covenants were effectively used to keep blacks out of most of Cincinnati and forced overcrowding in the few neighborhoods where they could settle. Knowing that tenants had no alternative, landlords in these black neighborhoods often inflated rent prices, neglected maintenance on properties and shoddily modified single family homes into multiple apartments.

Fortunately, not everyone turned a blind eye to the mistreatment of the blacks who had come here hoping find homes and had found rat infested slums instead. From 1911 to 1914 businessman and philanthropist Jacob Schmidlapp built 96 homes open to all races around the city and formed the Model Homes Company which built Washington Terrace Apartments in Walnut Hills in 1915. Other similarly minded citizens founded the Better Housing League (BHL) in 1916 and sought to provide decent, affordable housing to both races. Unfortunately, the group found that ridding the city of slums was simply not economically possible and set their focus on providing newer homes for the middle class with the hope that the older homes would then go to low income citizens (Casey-Leininger p. 3). As great as efforts by the Model Homes Company, the Better Housing League and the Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA) were, they simply could not keep up with the rapidly growing population of blacks in Cincinnati. By 1930 roughly 64% of the total black population of Cincinnati was packed into the West End’s slums alone, paying high rent and living in unsanitary conditions. By 1943 the problem was so out of hand that vacancies in neighborhoods which allowed black residents were down to only .3%. This caused even more problems for civic housing groups like CMHA whose goal was to create integrated housing where whites and blacks would live side by side. When the housing projects were completed blacks rushed from places like the West End which were bursting at the seams while whites, who had no trouble finding homes, never came knocking so that the projects were successful in that they helped with the overcrowding, but failed to provide truly integrated housing, didn’t provide any help for Cincinnati’s middle-class black citizens and usually eventually turned into slums themselves.

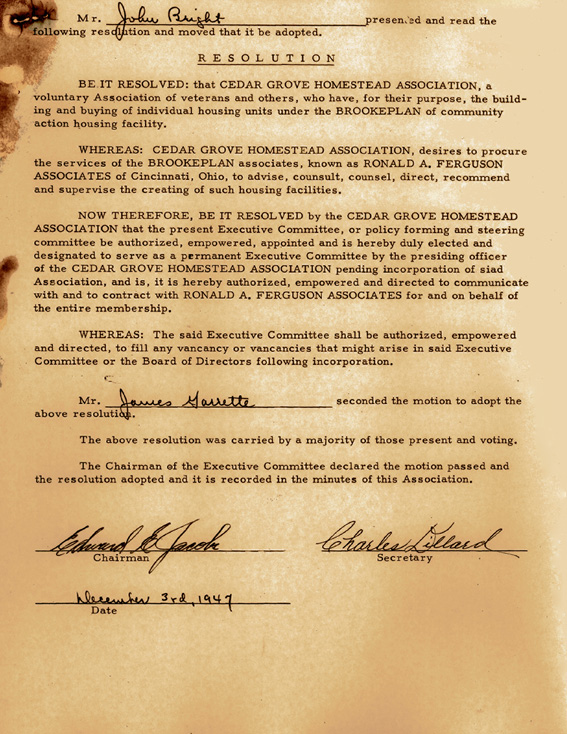

In 1947, Berry and a few other middle and working-class black citizens set out to create a neighborhood of single-family homes on large lots to provide decent living conditions at an affordable price. The first official meeting was held on November 26, 1947 at the Lincoln Heights branch of the YMCA where it was explained that the proposed Homestead Association would lower costs by using building techniques laid out by The Brookeplan method of project management. Key aspects of the plan included: “designing several functional basic floor plans, based upon size of project; creating several different exterior elevation designs for each plan; infrequent repetitive use of design in widely separated parts of the project; contract material supplies in carload quantities direct; employing highly skilled technical and professional advisors; most careful analysis and study of all branches and items necessary to produce finished lot and home.” Anyone who has lived in or had a home built by a major developer knows that these practices, new in 1947, are in widespread use across the country today and make for efficient use of product and time when building homes. This efficiency would be the key to success for the development in that it ensured that resultant homes would be affordable for black families in Cincinnati.

In 1947, Berry and a few other middle and working-class black citizens set out to create a neighborhood of single-family homes on large lots to provide decent living conditions at an affordable price. The first official meeting was held on November 26, 1947 at the Lincoln Heights branch of the YMCA where it was explained that the proposed Homestead Association would lower costs by using building techniques laid out by The Brookeplan method of project management. Key aspects of the plan included: “designing several functional basic floor plans, based upon size of project; creating several different exterior elevation designs for each plan; infrequent repetitive use of design in widely separated parts of the project; contract material supplies in carload quantities direct; employing highly skilled technical and professional advisors; most careful analysis and study of all branches and items necessary to produce finished lot and home.” Anyone who has lived in or had a home built by a major developer knows that these practices, new in 1947, are in widespread use across the country today and make for efficient use of product and time when building homes. This efficiency would be the key to success for the development in that it ensured that resultant homes would be affordable for black families in Cincinnati.

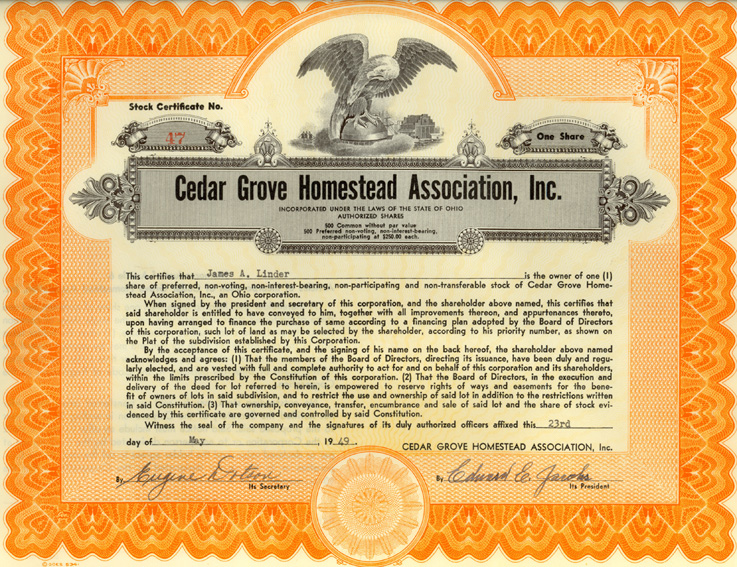

The Association really got underway at the next few meetings where it was decided that it would be called the Cedar Grove Homestead Association and the following officers were elected: Edward Jacobs, Chairman; Ben Carter, Vice Chairman; Charles Dillard, Secretary; Arthur Evans, Treasurer; Charles Sykes, Assistant Treasurer; and Attorney Theodore M. Berry, Counsel. Cedar Grove quickly began selling stock in the co-op as memberships in order to finance the purchase of land for the development. Common stock, a holder of which would be entitled to one vote in the association, cost members $50 while preferred stock, like the orange certificate above, sold for $250 and counted for no votes but would be put toward the purchase price of a house upon project completion and would contribute to development costs incurred by Cedar Grove until that time. On May 28, 1948, less than a year after its initial formation, Cedar Grove Homestead Association had the funds available to authorize Berry to begin negotiations to purchase a 93 acre tract of land. The final price for the land: $17,500. Unfortunately, getting the owner to sell to an association made up entirely of African Americans wasn’t so easy…

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $61,287 grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the Archives and Records Administration to fully process the Theodore M. Berry Collection in the Archives & Rare Books Library. All information and opinions published on the Berry project website and in the blog entries are those of the individuals involved in the grant project and do not reflect those of the National Archives and Records Administration. We gratefully acknowledge the support of NARA.