By Laura Laugle

It seems that smear campaigns fueled by fictitious rumors are nothing new to politics. Of course, most have known this to be true for quite some time. In fact, politicians in ancient Greece began pulling the proverbial wool about five minutes after the words demos and cratos were combined, but here we have one more piece of evidence to add to the already mountainous pile.

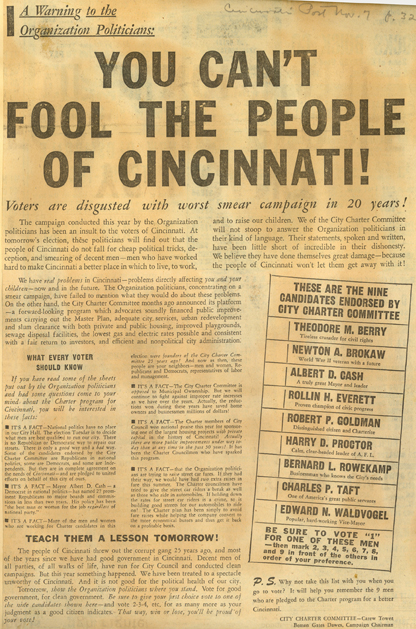

In 1949 Theodore M. Berry was endorsed by the City Charter Committee, a fusion of democrats, independents and republicans held together by the unifying wish to uphold the City Charter, to run for a seat on the Cincinnati City Council. Berry was the first African-American to be endorsed by the City Charter Committee and, if successful, would be the second non-white to sit on Cincinnati’s City Council.

In 1949 Theodore M. Berry was endorsed by the City Charter Committee, a fusion of democrats, independents and republicans held together by the unifying wish to uphold the City Charter, to run for a seat on the Cincinnati City Council. Berry was the first African-American to be endorsed by the City Charter Committee and, if successful, would be the second non-white to sit on Cincinnati’s City Council.

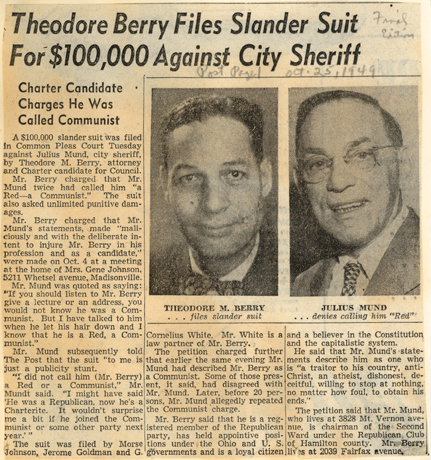

In a statement printed in the Cincinnati Edition of the Pittsburgh Courier on October 29, 1949, Berry stated that “’a whispering campaign’ had been conducted against him for many months.” The article to the right details the first incidence which Berry was able to attribute to a specific person.

Though sources give at least three different versions of the actual quote, allegedly Sheriff Julius Mund, a Republican Second Ward committeeman, was attending a political talk where he said something along the lines of “If you should listen to Mr. Berry give a lecture or an address, you would not know he was a Communist, but I have talked to him when he has let his hair down and I know he’s a Red.” According to Berry, this statement came as a shock to those of his supporters who were present at the meeting who then reported the incident to Berry afterwards. Upon hearing of the incident, Berry stated that it was a deliberate and malicious attack on his candidacy and filed a $100,000 suit against the sheriff for the slanderous comment.

Berry also claimed that the “Red” label was a result of his strong stance on civil rights and his connections with the American Civil Liberties Union, an organization which took a strong position against Senator Joseph McCarthy’s methods for uncovering “subversives” in the United States. At the time of Mund’s statement, Berry was embroiled in a struggle against the Cincinnati Board of Education over a housing issue in the West End. The board planned to evict 200 families from their homes in the middle of the following January in preparation for the construction of new school buildings. Berry, citing the tight housing market, pushed the Board of Education to delay the demolition of the homes until the affected families could be relocated, and not to “push its program ‘to the detriment of human need.’” This is the kind of humanist behavior which was twisted by Berry’s opponents to look like Communist sympathizing. It is true that the fear of spies “living among us” was a legitimate one. After all, Soviet Russia was a properly scary place and Stalin was a paranoid and tyrannical despot who was perfectly fine with making his own people “disappear,” but it was important then, just as it is now, to think critically about a person and his or her actions before making or believing such comments.

Despite the dirt being flung at him, Berry won the 1949 campaign and secured his seat on City Council for a two year term beginning in 1950 when he worked tirelessly for civil rights and led the council in issuing a resolution to allow West End residents more time to find housing. Berry was elected to council five more times trough the 1950s, 60s and 70s before becoming the Mayor of Cincinnati in 1972. As for the lawsuit, I have yet to discover how it was resolved, but I hope something further will be revealed during my continued research.

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $61,287 grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the Archives and Records Administration to fully process the Theodore M. Berry Collection in the Archives & Rare Books Library. All information and opinions published on the Berry project website and in the blog entries are those of the individuals involved in the grant project and do not reflect those of the National Archives and Records Administration. We gratefully acknowledge the support of NARA.