By Laura Laugle

I recently came across a transcription of a deposition which Theodore M. Berry gave after being subpoenaed for the school desegregation case Bronson v. Board of Education of Cincinnati. During that deposition and much to Berry’s annoyance at what he called the “terrific waste” of everyone’s time and money, lawyers from all sides of the case had Berry go into great detail about many aspects of his life. He told of his time at the Stowe School, he told of his work as a young lawyer and he told of the Tuskegee Airman case.

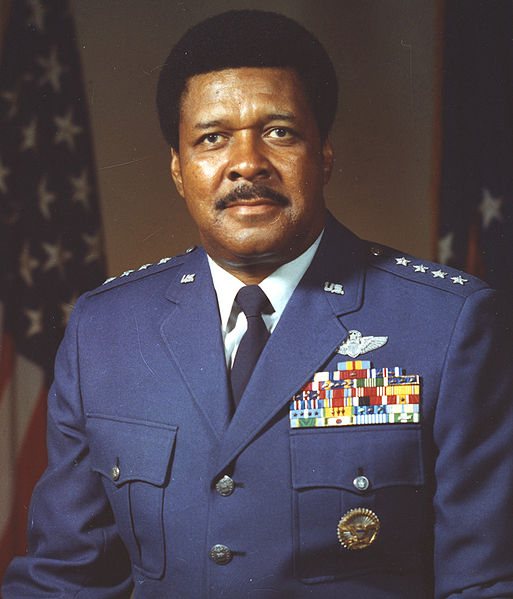

“There were occasions in the early days during the period of Thurgood Marshall, when he was the special counsel, this goes back before the war, when I have been consulted, but never was a counsel of record in any case, except a very celebrated court-martial, in which I served as chief counsel in representation of a group of Negro officers who were being court-martialed because they protested against the segregated officers’ quarters. I was chief counsel, Lieutenant William T. Coleman, who more recently was Secretary of Transportation, was military counsel associated with me, and one of the defendants who were acquitted became one of the first black Air Force generals, General Chappie Jones (James), he was one of the officers. He later acknowledged had he not been acquitted at that court-martial, he might not have become a general.”

In fact, Daniel “Chappie” James went on to become America’s very first African American Four Star General. Just after receiving his fourth star in 1975 he described the incident in an article in the Journal Herald called “Black General Fought his Way Up” by William Greider. “I was in the first wave arrested, then we persuaded others. The damn thing started to escalate and pretty soon every black officer in the place was marching on the officers’ club, demanding to be arrested.” Although Chappie was taken into custody initially and was technically “under arrest” until charges were dropped against the 101 officers after the court martial of Thompson, Clinton and Terry, he was released almost immediately because his flying skills were needed. What the military didn’t know was that when Chappie was flying around the United States delivering supplies, he was also getting the word out to the public about how blacks were treated in the US Air Force. In a 1977 interview with Michael Coakley of the Chicago Tribune he said “I’d be flying missions to Dayton or Louisville and while I was there I’d slip over to the newspapers and give them a pile of news releases on what was going on. Boy, they’d have killed me if they’d known I was doing that – with military aircraft.” I don’t think even Berry’s masterful oratory could have gotten him out of trouble if he’d been caught handing press releases to sympathetic newspapers, but that was a risk worth taking for good reason. People willing to take that chance helped change the way the world works.

I always love coming across something seemingly small and insignificant, like Berry’s quick mention of Chappie in the quote above, which when followed along its natural route, leads to a great learning experience. And things like that happen so often in the Archives and Rare Books Library.

For more information on the Tuskegee Airmen court martial and Daniel “Chappie” James please see:

Blog Post “T. M. Berry Project: The Tuskegee Airmen Case of 1945”

Daniel “Chappie” James: The First African American Four Star General by Earnest N. Bracey, 2003

And

African Americans in the Military by Catherine Reef, 2004

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $61,287 grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the Archives and Records Administration to fully process the Theodore M. Berry Collection in the Archives & Rare Books Library. All information and opinions published on the Berry project website and in the blog entries are those of the individuals involved in the grant project and do not reflect those of the National Archives and Records Administration. We gratefully acknowledge the support of NARA.