By Laura Laugle

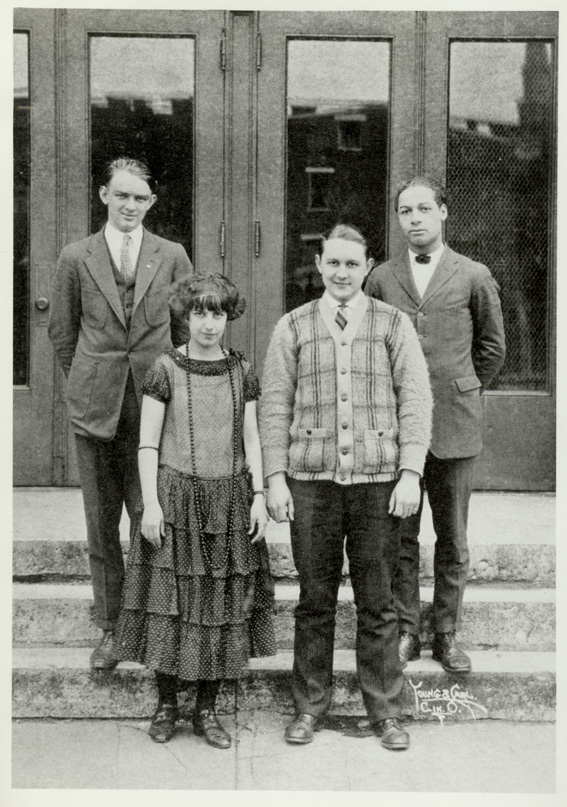

Theodore M. Berry with his Woodward High oration competitors Charlotte Lightfield, Nelson Murphy, and Aston Welsh, 1924

For those readers who have kept up at all with these blog posts, it will come as no surprise that Theodore M. Berry played a major role in aiding the civil rights movement in Ohio, and more particularly in Greater Cincinnati. What may be surprising to those who don’t know much about his life, though, is the way he went about it – firmly but politely and, most importantly, effectively. This was and continues to be, in this archivist’s humble opinion, one of his greatest contributions to the cause. For many people who were not witness to “the civil rights movement,” that term conjures images of the race riots which took place in Avondale, Detroit, and Watts during the 1960s, or of militant Black Panthers like those depicted in the film Forrest Gump. Berry, however, took a very different tack right from the start, believing the only way to extinguish the fire of discrimination would be to invalidate the prevailing stereotypes about African Americans which fed its flames. Well before he ever had the idea of becoming a city councilman, a personal liaison for a United States presidential candidate, or the director of a federal agency, Berry simply strove to be the best that he possibly could be. He broke down a number of walls in doing so.

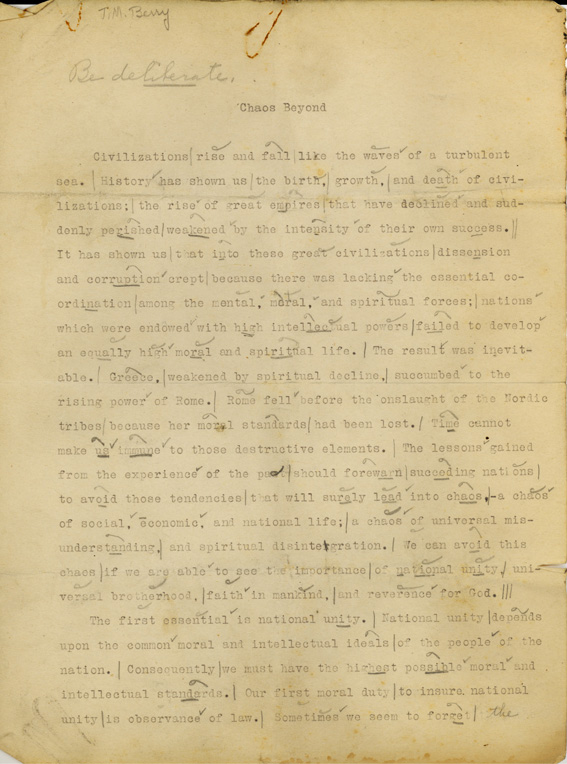

As a student at Woodward High School, young Berry must have surprised and impressed even the most bigoted of his peers and teachers. For much of his high school career, he was effectively homeless and had an address only at the “Negro YMCA” on 9th Street downtown. And yet, he managed to consistently produce exemplary work. Nearing graduation in 1924, Berry entered the speech writing contest which would determine the class orator and valedictorian. His speech was judged by the faculty to be the winner and he would walk with the class president down the aisle at Cincinnati Music Hall to deliver it to the graduating class and their families and friends. This plan created quite a controversy when people realized that the valedictorian, a black boy would be walking with the class president, a white girl. The school decided to have the orators submit new essays, this time using pseudonyms, from which the faculty would choose a valedictorian. Berry chose the pseudonym “Tom Playfair” when he submitted his speech “Chaos Beyond.” Again, his essay was chosen and he was named valedictorian. The school deemed it more appropriate to have the two students approach the stage separately, so Berry walked alone to deliver the speech, which wowed an unwillingly impressed audience and which he would remember well into his 90s.

As a student at the University of Cincinnati, Berry fought to have black students included in campus activities and helped found a magazine made for and by African American students called The New Horizon.

As a student at the University of Cincinnati, Berry fought to have black students included in campus activities and helped found a magazine made for and by African American students called The New Horizon.

Shortly after graduating from Cincinnati Law School in 1931, Berry was elected president of the local NAACP. In an interview with Cincinnati Post staffer David Wecker in August of 1993, Berry said of his time as NAACP president, “Those six years were pursued on the theory of trying to pursue change from without. I never felt ordained to be an agent of change, but most of my efforts have been to effect [sic] some form of social change. And I realized the progress I was making in that regard with the NAACP was yielding poor results. So I changed my tactics and began working from within.”

It was when he went back to working with state and city government that Berry really began making strides for civil rights in Ohio. Armed with the knowledge he gained while conducting a survey of African American employment in Cincinnati for the Welfare Department in 1930, Berry began the long fight for equal employment opportunity for blacks in Ohio.

During World War II, with the industrial war machine going strong and billions of dollars worth of federal contracts coming into the Cincinnati area alone, FDR created the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC), the federal office which would be responsible for bringing able-bodied workers, regardless of skin color, into the work force. But even then, Berry saw there were pervasive problems in the Cincinnati area. In a letter to Dorothy S. Mathers of the Woman’s City Club he stated “…by refusing to employ Negro women in war production, the producers of war goods in this vicinity are in effect, immobilizing essential and available woman power.” In 1945, when the war machine ground to a halt and its non-white/non-male cogs were thrown out to fend for themselves, the FEPC was disbanded and the responsibility of creating fair employment legislation was handed back to the states. It was then that Berry became chairman of the Ohio Committee for Fair Employment (OCFE). The state of Ohio failed for many years to pass a fair employment bill but as Vice Mayor in 1957, Berry managed to get a bill through Cincinnati City Council. Finally, after a 14-year fight for Berry and the OCFE, the State of Ohio under Governor Michael DeSalle passed fair employment legislation in 1959.

Berry’s commitment to the “people helping people” ideal made him more than an African American activist – he was a human activist who acted on behalf of all peoples unfairly treated. I believe that it was this attitude and Berry’s willingness to work hard with anyone and everyone willing to help which brought about the permanent change which would not have been achieved in any other way.

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $61,287 grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission of the Archives and Records Administration to fully process the Theodore M. Berry Collection in the Archives & Rare Books Library. All information and opinions published on the Berry project website and in the blog entries are those of the individuals involved in the grant project and do not reflect those of the National Archives and Records Administration. We gratefully acknowledge the support of NARA.