Often when I tell family or friends that I’m going to be going to an archives conference, they say “How Boring!” I find it exciting though. It is my chance to see what other archivists are doing, if there is anything new we can try here at UC, and it allows me to meet other archivists who might be able to answer one of my questions or one of your future questions. I recently attended the Midwest Archives Conference Annual Meeting in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and learned about some new projects using “participatory archives,” and how these collections can be used in research, teaching, learning, and just for fun. (To learn a little more about the conference, read Stephanie Bricking’s blog post about her poster presentation on the Sabin papers.)

What is a participatory archive? The plenary speaker, Kate Theimer, who is a popular blogger in the archives world, defines it as:

An organization, site, or collection in which people other than archives professionals contribute knowledge or resources, resulting in increased understanding about archival materials, usually in an online environment.

Basically, it is a way to integrate web 2.0 technologies into digital collections and gain the thoughts, ideas, and collective knowledge of the audience. Sometimes it even becomes a way for people to contribute their own material to a collection. It really is not completely new, but this format of digital collection is quickly gaining ground.

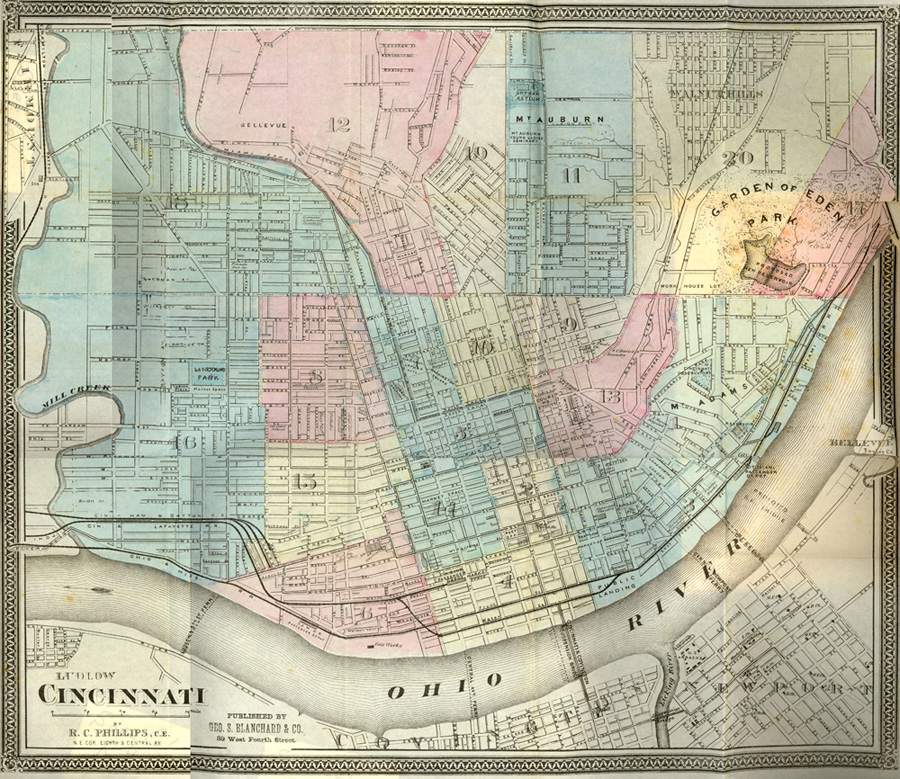

Participatory archives often solicit the assistance of the public in identification of archival materials or help in making historical material more useful. One example is the Remember Me? project by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum which utilizes the knowledge of their visitors to discover the identities of children displaced by the Nazis and the Axis during World War II. This digital collection displays pictures of children who survived the atrocities and visitors can leave comments on or suggestions as to where the children are now. The site has enjoyed some success, such as in the case Liliane Wahlberg and her siblings. Another project, the New York Public Library’s Map Warper, also utilizes the minds of visitors to help align historical maps with a current map. If you have ever questioned what a road used to be called, or wondered what a building used to be, you can certainly understand the usefulness of such a project.

Other participatory archives have sought to gather material from the public to commemorate events or to increase their holdings on specific topics. The Library of Virginia’s CW 150 Legacy Project is collecting material documenting the Civil War from throughout Virginia, digitizing it, and making it available through their website. Likewise, the Denver Public Library’s Creating Your Community project facilitates community created archives by allowing participates to upload photos and documents from their individual collections and add stories about their own experiences. Archival communities have been created for neighborhoods, churches, art, schools, music, and other parts of Denver life. It’s a great way to learn about the history of Denver and its people.

Another project where any individual can contribute their own material is History Pin. History Pin allows you to post historic photographs on a map at the location of those photos. You can also post stories and leave comments. At the Midwest Archives Conference, Elizabeth Reilly of the University of Louisville talked about using History Pin to display photographs of Louisville, Kentucky. The University of Louisville staff uses images in their collections that match the view from Google’s street view. See some examples here by clicking on the pins with the little yellow Google street view guy: http://www.historypin.com/photos/#!/geo:38.217238,-85.746229/zoom:12/

These are great projects that can engage researchers and patrons in the archives and allow them to learn about and contribute to archival collections. Being at a university, though, it is important for us think of the ways that participatory archives can be used for teaching and for research. Old Weather is an example of how participatory archives can be used for research. Old Weather hopes to make available weather data from the past utilizing individuals to transcribe historical ship logs. The data will then be used to produce climate models. Other participatory archives can create opportunities for student projects. The New York Public Library’s What’s On the Menu project, which recruits participants to transcribe digitized menus, makes its data available for anyone to use to create tools or games.

Archivists have only begun creating participatory sites like these. If you’re interested in seeing what else is out there, more projects are listed on Kate Theimer’s blog ArchivesNext. Hopefully, a taste of a few of these will get your creative juices flowing, allow you to learn something new, or at least have a little fun.