Below is the second in a series of blogs in which Jack Davis discusses Joseph Alsop and his papers in ARB. It was originally published on From the Archivist’s Notebook, a blog of Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan, head of the archives at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

By: Jack Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati

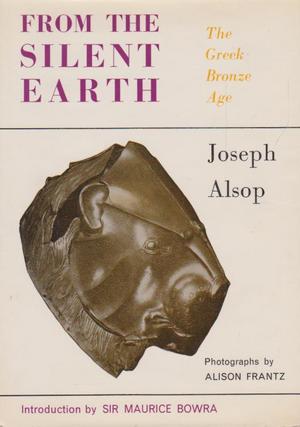

Searching library catalogues and online archival finding aids sometimes produces unexpected consequences. As I wrote in Part I of this two-part post, Joseph Alsop’s principal archive is curated in the Library of Congress. The University of Cincinnati Archives and Rare Book Library, however, contains five boxes of manuscripts of From the Silent Earth and relevant correspondence between Alsop and the eminent scholars Emmett Bennett, Carl Blegen, Maurice Bowra, John Caskey, Sterling Dow, and Leonard Palmer. While writing From the Silent Earth: A Political Columnist Reports on the Greek Bronze Age (1964), Alsop solicited advice from these distinguished Aegean prehistorians and Classical philologists, all of whom were supportive of his efforts. Jack Caskey, for example, replied to an initial letter of inquiry: “I’m particularly interested in absorbing your political analysis. It sounds neither foolish nor pretentious to me in your brief summary.”

Searching library catalogues and online archival finding aids sometimes produces unexpected consequences. As I wrote in Part I of this two-part post, Joseph Alsop’s principal archive is curated in the Library of Congress. The University of Cincinnati Archives and Rare Book Library, however, contains five boxes of manuscripts of From the Silent Earth and relevant correspondence between Alsop and the eminent scholars Emmett Bennett, Carl Blegen, Maurice Bowra, John Caskey, Sterling Dow, and Leonard Palmer. While writing From the Silent Earth: A Political Columnist Reports on the Greek Bronze Age (1964), Alsop solicited advice from these distinguished Aegean prehistorians and Classical philologists, all of whom were supportive of his efforts. Jack Caskey, for example, replied to an initial letter of inquiry: “I’m particularly interested in absorbing your political analysis. It sounds neither foolish nor pretentious to me in your brief summary.”

In Part I, I explored how it was that one of Washington’s foremost political analysts of the Cold War era (and for two decades a trustee of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens) came to write a book about the Greek Bronze Age. In Part II, I describe the contents of the archive in Cincinnati, discuss its academic significance, and consider what light it sheds on Alsop’s research methods.

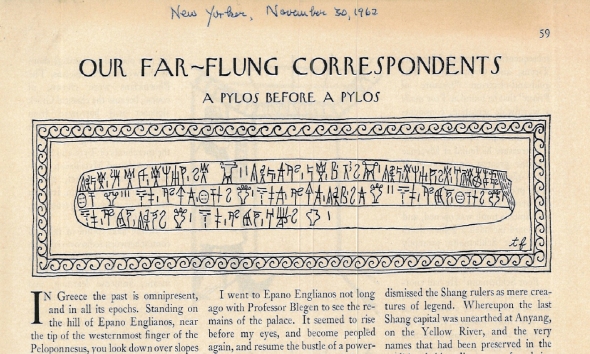

Four of five boxes (#1-3 and 5) either contain drafts of Alsop’s 1962 article about Blegen in The New Yorker or From the Silent Earth. In several instances, the manuscripts are annotated in the hands of the aforementioned scholars, who served as Alsop’s unofficial advisory panel. The most valuable part of the archive consists of letters in Box 4, in which views are expressed about Aegean prehistory that Alsop’s correspondents might have been reluctant to put in print. We find in them an entrée into the world of academic politics at a time when debate over the dating of Linear B tablets found by Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos was raging.

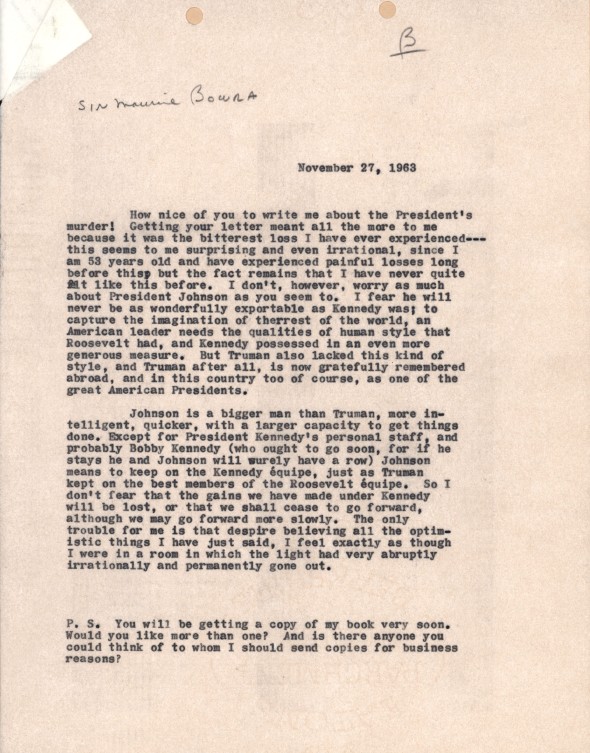

The correspondence with Sir Cecil Maurice Bowra (1898-1971) is most extensive, since this relationship was long-standing and operated simultaneously on social as well as academic planes. Five days after Kennedy’s assassination Alsop wrote to Bowra: “I feel exactly as though I were in a room in which the light had very abruptly irrationally and permanently gone out.”Alsop was condescendingly frank about the scholars who had helped him write From the Silent Earth. Referring to the dinner in Georgetown planned for December 14, 1963 (see Part I), he remarked to Bowra: “I wish you might be here, for you have helped me more than anyone but I am not quite sure that you would enjoy Professor and Mrs. C.C. Vermeule, Dr. Alison Frantz, Professor and Mrs. Sterling Dow, Professor and Mrs. E. L. Bennett, Jr., just as I am not entirely sure Susan Mary will enjoy them.” He was more excited about the prospect of having Bowra attend a dinner the following month: “Are there others you want to see, other than the [McGeorge] Bundys, the [Dean] Achesons … We have asked our grandest and most monstrous monster the Secretary of Defense, Bob McNamara, to the dinner on Monday. I plan to ask the President, too, not for our sake, I must rudely add, but because I think he will greatly enjoy meeting you.”

Alsop writing to Bowra about President Kennedy’s assassination (Archives and Rare Book Library, University of Cincinnati)

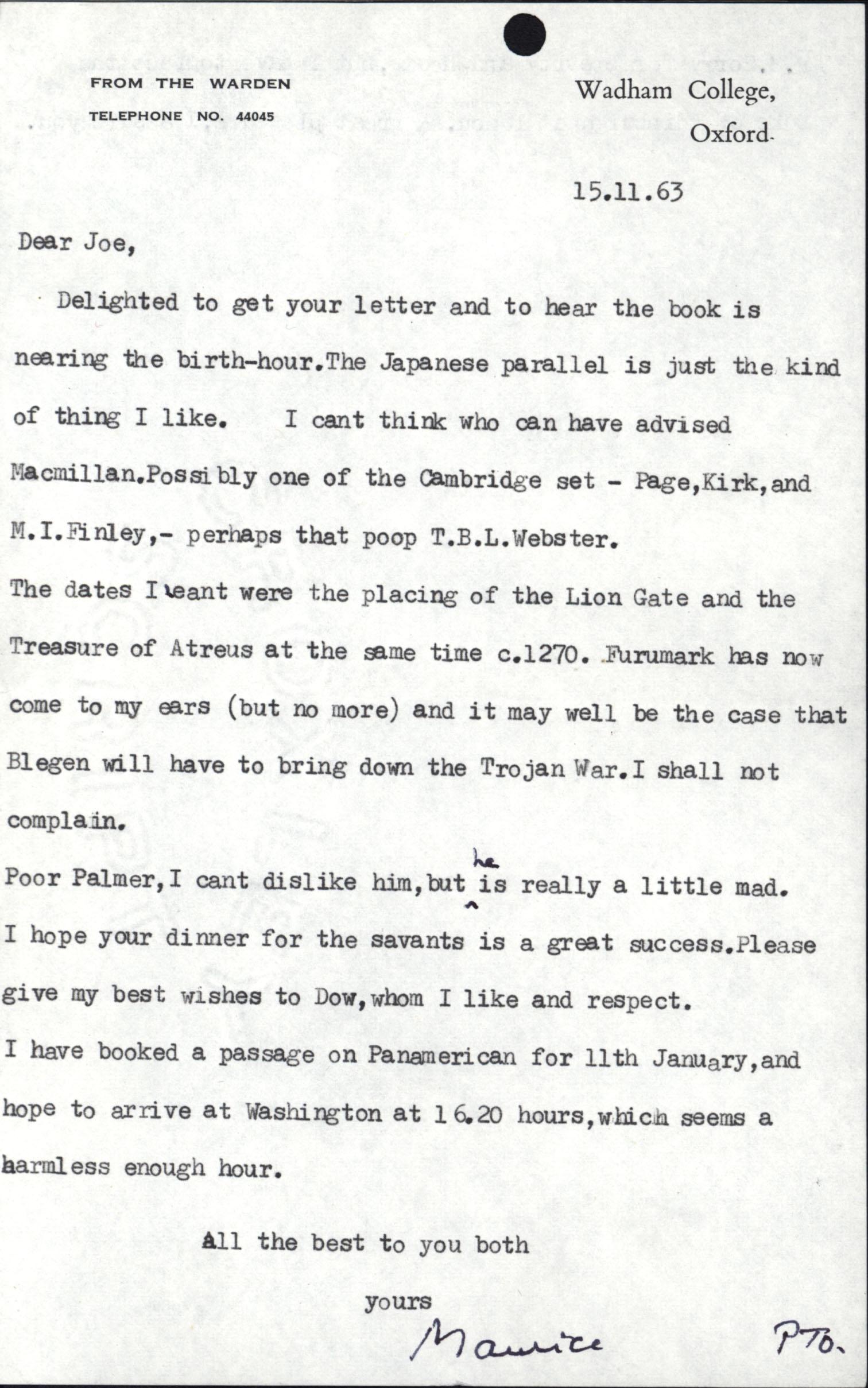

Both Bowra and Alsop were fond of gossip, archaeological and political. Alsop commented snidely on the chronological scheme proposed for the dating of beehive tombs at Mycenae by George Mylonas, professor at Washington University in St. Louis, “Blegen was critical of it in detail, just as Mylonas is even more critical of Blegen.” Bowra could be more caustic. He had no respect for the Duke of Edinburgh, Moses Finley, or especially for T.B.L. Webster (whom he called a “poop”).

Confidences are shared. A humorous remark by Bowra about the Profumo Affair implies that these two men, though closeted, were open with each other about their sexual orientation: “Sandys name is much in the news. You no doubt saw the admirable letter in ‘The Observer’ pointing out what a grave security risk heterosexuals are in high office.” (In 1957, the KGB had entrapped Alsop himself in a compromising situation with one “Boris,” and had then attempted to blackmail him with surreptitiously taken photographs.)

Alsop’s other correspondence is more strictly professional and the scholars who helped him write From the Silent Earth were mostly new acquaintances. Nonetheless, their letters to him, and his to them, shed light on his methods. He was first and foremost a journalist and his technique I would call “composition by consultation.” In the preface to his book about art collecting, The Rare Art Traditions, he claimed that he began that work imagining that he would “consult the best authorities in the languages known to [him] …”. But that strategy was not sufficient, since there was too much subject matter that he could not himself master. He needed to question experts. For From the Silent Earth he, for example, needed to ask Emmett Bennett about Mycenaean warfare, the House of the Oil Merchant at Mycenae, Mycenaean dress—also where Pa-ki-ja-na, a religious center referenced in Linea B tablets from Pylos, was located, and how he should imagine it.

Bowra advising Alsop on issues of Mycenaean chronology (Archives and Rare Book Library, University of Cincinnati)

Sterling Dow was Alsop’s real guiding light, recommending From the Silent Earth to Harper and Row and critiquing the entire manuscript. In this period of his life Dow was studying early Greek literacy, an interest that culminated in his 1971 contribution (with John Chadwick) to the second edition of the Cambridge Ancient History. A comradery quickly developed, and Alsop and Dow planned to travel to Crete together in the summer of 1963. Alsop confided in Dow: “I don’t want to be sentimental but at my age it is not often that one seems to have made a new friend and I do feel that in your case.”

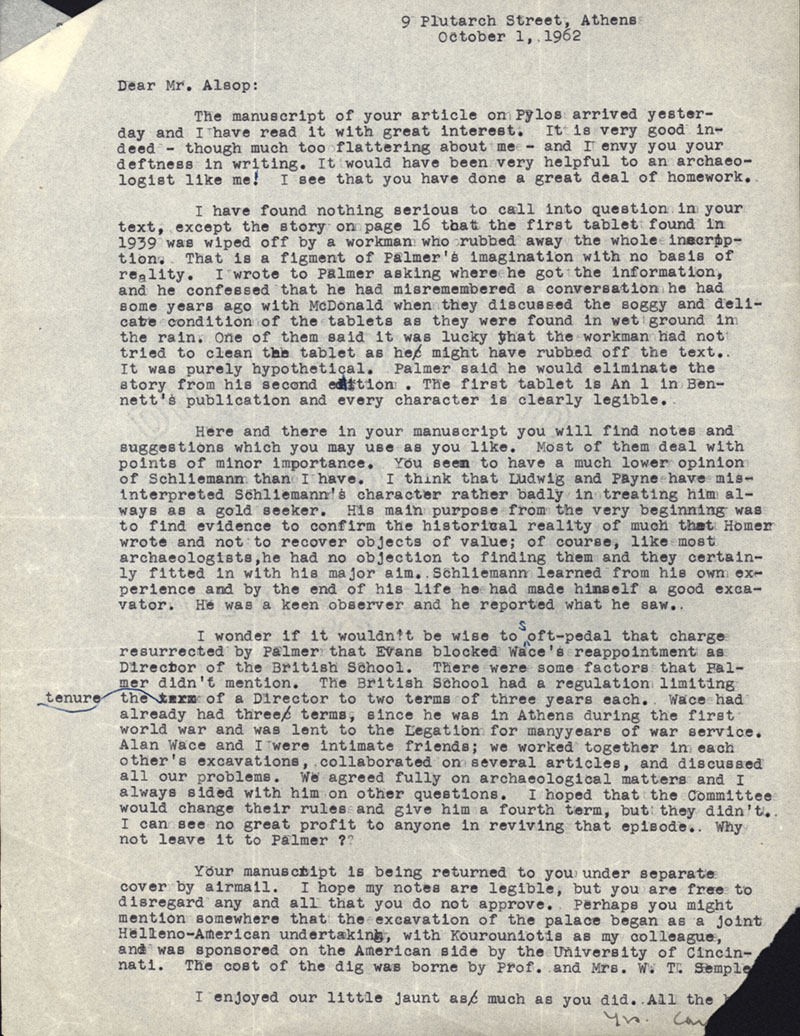

But the exchanges between Carl Blegen and Alsop are of particular academic interest since they shed light on a supposed “quarrel” between Sir Arthur Evans and Alan Wace, a subject that has been explored in two recent studies published in N. Vogeikoff-Brogan, J. L. Davis, and V. Florou, eds., Carl W. Blegen: Personal and Archaeological Narratives [Lockwood Press, 2015], one by Yannis Fappas (“The ‘Govs’ of Mycenaean Archaeology: The Friendship and Collaboration of Carl W. Blegen and Alan J. B. Wace as Seen through their Correspondence”), the other by Yannis Galanakis (“’Islanders vs. Mainlanders,’ ‘The Mycenae Wars,’ and Other Short Stories: An Archival Visit to an Old Debate”). As Aegean prehistorians well know, Wace and Blegen strongly disagreed with Evans about the nature of the relationship between Crete and the Greek mainland in the earlier centuries of the Late Bronze Age. They contested Evans’ claim that Crete had been culturally and politically dominant over the mainland since the time of the Schliemann Shaft Graves at Mycenae.

Such differences of opinion, in Galanakis’s words,“soon turned into an academic and public controversy, especially after Wace’s first excavation season at Mycenae in 1920. In an article published in The Illustrated London News that same year, and written by Evans’s friend, David Hogarth, we read: ‘Islanders, led by British Cretans, offer battle to Mainlanders, led by British Athenians. Might not deeper examination show that the Argolid developed its own culture from the Stone Age up to the capacity to produce for itself the jewels of the Shaft Graves? The dispute will be conducted according to the rules of scientific war—war of the kind that brings peace, not a sword, and light out of darkness.’” By the 1950s the debate hinged on the date of the Linear B tablets Evans had found at Knossos. Were they really as early as 1450 B.C.? A challenge to Evan’s methods, even his personal integrity, was fueled by the decipherment of Linear B as Greek in 1952. The large cache of Linear B tablets found by Blegen in the Palace of Nestor at Pylos came from destruction levels, ca. 1200 B.C., apparently much later than those at Knossos.

Such was the professional and public face of the controversy. But what happened behind the scenes? Galanakis has concluded that: “Despite profound disagreement on archaeological matters, the archival material I was able to examine suggests that personal relations between Evans and the ‘Govs’ (i.e., Wace and Blegen) remained very good. Some scholars have suggested that Wace’s career suffered because of this archaeological dispute and that it was Evans who was ultimately responsible for the ‘sudden halt,’ as they describe it, of Wace’s work at Mycenae and the termination of his tenure as director of the British School in 1923. Yet the view one gets from the letters is quite different: Wace knew a year and a half in advance that both his directorship and the Mycenae excavations would come to an end. Moreover, in one of the letters to Evans, Wace asked him ‘whether I could give your name as one of my referees, when on my return to England, I will start applying for jobs.’ In 1934, Evans would support Wace’s application for the Laurence Chair in Classical Archaeology at Cambridge: ‘I am glad to enclose your recommendation for this post, though I really do not think you need it!’ (referring to the recommendation letter, not the post).”

Yet correspondence between Alsop and Blegen suggests that Evans may actually have impeded the development of Wace’s career. Since drama made good reading, Alsop had in first drafts chosen to emphasize conflict between Wace and Evans, thus evoking strong reactions from Blegen. Blegen wrote in response, in October 1962 when he received Alsop’s draft of “A Pylos Before Pylos”: “I wonder if it wouldn’t be wise to soft-pedal that charge resurrected by Palmer that Evans blocked Wace’s reappointment as Director of the British School. There were some factors that Palmer didn’t mention. The British School had a regulation limiting the tenure of a Director to two terms of three years each. Wace had already had three terms, since he was in Athens during the First World War and was lent to the Legation for many years of war service. Alan Wace and I were intimate friends; we worked together in each other’s excavations, collaborated on several articles, and discussed all our problems. We agreed fully on archaeological matters and I always sided with him on other questions. I hoped the Committee would changed their rules and give him a fourth term, but they didn’t. I can see no great profit to anyone in reviving that episode. Why not leave it to Palmer?”

The following year, while writing From the Silent Earth, Alsop returned to the subject, writing to Blegen in August 1963: “As to the matter of Wace’s failure to be reappointed to the Directorship of the British School, I know I have been a little obstinate about this, because Maurice Bowra and all my other English friends who happen to be acquainted with the inside story, have told me that Wace would unquestionably have been reappointed except for Sir Arthur Evan’s venomous opposition. The anecdotes of the Evans-Wace episode are indeed fairly hair-raising, but only as they relate to Sir Arthur, I should add.” In the end, however, Alsop relented, and Blegen thanked him for doing so in October 1963: “I was glad to see your new version dealing with Evans: it is, in my judgment, a great improvement over what you first wrote (which seemed to me to reflect too much of Palmer’s coloring) and more in line with the facts. Wace had already served three terms as Director. We were always, he and I, very close friends and I’m sure he would prefer the revised text.” Blegen did not, however, deny the accuracy of Bowra’s views or of Alsop’s original text.

I end this, the second part of my post, with more general thoughts about Joseph Alsop and Greece. It is not hard for me to understand his love for ancient Greece, since he was the product of an educational system that emphasized the significance of the Classical tradition. But, as a political analyst too, Alsop had a long-standing interest in modern Greece. Two “Matter of Fact” columns, written in February 1947 with his brother Stewart, had exposed the extent of Truman’s concern over Communist infiltration in the Balkans, reporting that the United States was considering a “politico-economic fire brigade” to deal with problems. Alsop had also been influential in building public opinion in the United States in support of the Marshall Plan, against the opposition of Senator Robert Taft in particular. Brother Stewart had traveled to Greece in these years.

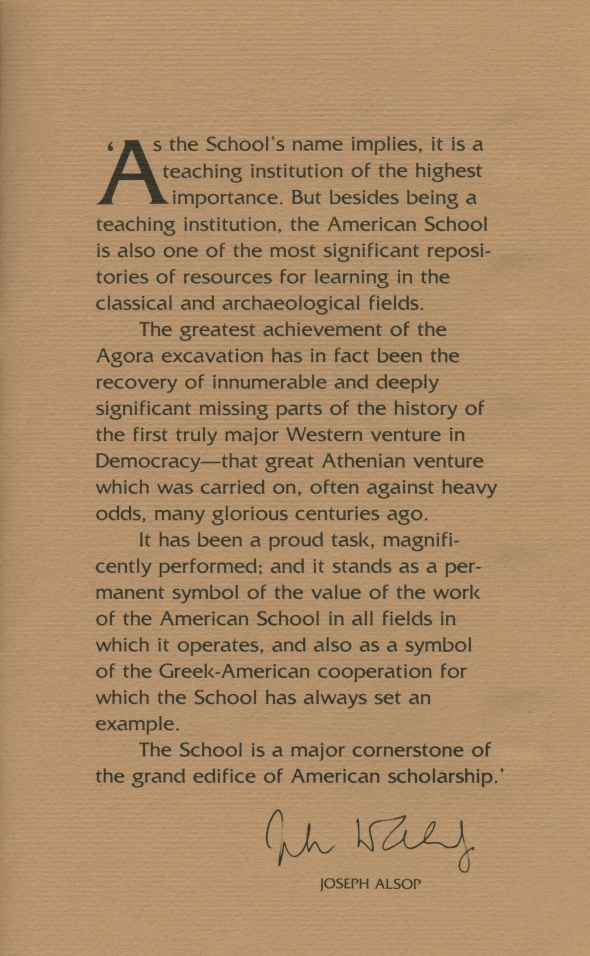

For the preceding reasons it seems hardly a surprise that Alsop’s associations with Greece lasted long after the publication of From the Silent Earth. He continued to correspond with Blegen until 1966, their final exchange being at the time of Elizabeth Blegen’s death in November of that year. After his retirement in 1974 he became even more involved in Greek affairs as a trustee of ASCSA (1965-1985). In that role he worked diligently with Betsy Whitehead, president of the Board of Trustees, to build the School’s endowment in its centennial campaign and he was responsible for arranging a congratulatory telegram from President Reagan. In the early 1980s he conducted a vigorous academic correspondence with fellow trustee Malcolm Wiener, once again on the subject of Mycenaean Knossos among others. Men like Alsop, though little known to scholars who today use ASCSA’s facilities in Athens, have worked since its foundation in 1881 to make the School what is today — a worldclass center of academic excellence that continues to thrive, even in challenging financial environments. They deserve our gratitude and remembrance.