Professor Jack Davis of UC’s Classics Department is a regular visitor to the Archives and Rare Books Library. Recently he has been examining the Joseph Alsop papers, which contain a manuscript copy of Alsop’s book, From the Silent Earth, a Report on the Greek Bronze Age and correspondence about the manuscript. Below is the first of a series of blogs in which Jack Davis discusses Joseph Alsop and the collection in ARB. It was originally published on From the Archivist’s Notebook, a blog of Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan, head of the archives at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

By: Jack Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Cincinnati

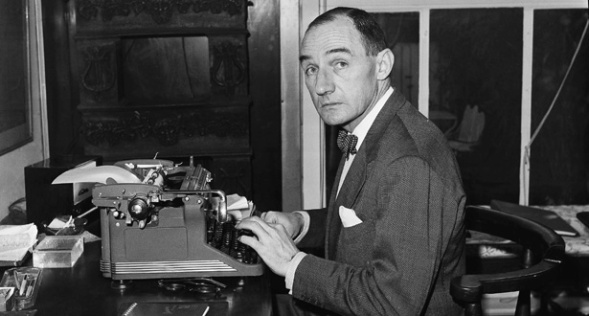

Several months ago Louis Menand’s New Yorker review (Nov. 10, 2014) of Gregg Herken’s The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington kindled my interest in Joseph W. Alsop (1910-1989), influential journalist, syndicated newspaper columnist, and trustee (1965-1985) of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. A bit of archival sleuthing at the University of Cincinnati (see below) led to the discovery that on Saturday, December 14, 1963, Alsop had summoned an A-list of Classical archaeologists and art historians to dine with him and his wife, Susan Mary, in their Georgetown, Washington, D.C., home — a strange flock for this longtime Washington insider to host.

Guests included Jack and Betty Caskey, professors at the University of Cincinnati, Emmett Bennett, professor at the University of Wisconsin, Emily Vermeule, then professor at Boston University, Cornelius Vermeule, curator of Classical art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and Sterling Dow, professor at Harvard.

Joe and Susan Mary regularly cultivated movers and shakers, and dinner parties were for them a means to an end. The Alsop home at 2720 Dumbarton St., N.W. was a focus for members of the so-called “Wasp Ascendency,” i.e., white Anglo-Saxon Protestant men who had risen to positions of highest political power in the United States. At boisterous Sunday night dinners, “zoo parties” as he called them, the Washington elite broke bread together, and Joe gathered scoops for this column, “Matter of Fact,” in The New York Herald Tribune. Alice Roosevelt Longworth, his cousin, commented in 1971: ”That’s the way Joe plays the game…I know that whenever I go over to Joe’s house for a dinner party I am working for him. I don’t mind a bit. I know Joe uses me. Good heavens, he uses everybody!”

The story goes that President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, after his inaugural balls, headed straight for the Alsops’ where he drank champagne and sipped terrapin soup, a house favorite. Academics, as well as politicians and journalists, were favored visitors. Sir Maurice Bowra, warden of Wadham College, Oxford, appeared often — so too did Hugh and Lady Antonia Fraser, friends of the Kennedys, and Oxford philosopher Isaiah Berlin. Berlin in 1941 described Alsop as “a fanatical Anglophile, intelligent, young, snobbish, a little pompous, and my permanent host in Washington.”

But the guests for dinner on Saturday, December 14, 1963 were not typical of the “Georgetown Set.” Alsop intended that night to honor and reward scholars who had contributed to the success of his new book, From the Silent Earth: A Report on the Greek Bronze Age (Harper and Row, 1964). The invitation was welcome: Sterling Dow relayed it to the Vermeules, then commented that “like me they look upon it as an EVENT second only to the capture of Knossos…” — referring to the Mycenaean conquest of Crete, an incident that Alsop himself considered second to none in importance for understanding the Bronze Age of Greece.

From the Silent Earth, although not well known today, was in 1964 the talk of the town. Maurice Bowra gave it his imprimatur, and it was generally well-received by reviewers. The book also sold well —reprinted in the U.K. in 1965, 1970, and 1981. The way to its popularity had been paved two years earlier by Alsop’s profile of Carl Blegen in the The New Yorker (“Our Far-Flung Correspondent: A Pylos before a Pylos,” November 24). Blegen there emerged heroic in his efforts to conquer the past.

In the wake of From the Silent Earth, Alsop was invited in 1965 to serve on the Board of Trustees of ASCSA — a responsibility that he took very seriously. His obituary, as reported in Akoue, newsletter of the ASCSA, described him as “a needling gadfly, a generous host, a genuine friend.” Rob Loomis, now secretary of the Board, recently wrote me: “At trustee meetings, he was fairly vocal, usually amusing, and of course rather eccentric in appearance, dress, accent, etc. He chain-smoked cigarettes on a long cigarette holder, causing great discomfort to Betsy Whitehead [president of the Board], who had emphysema. At one point, to ease our financial difficulties, he suggested that we sell the Lears [a rich collection of Edward Lear’s watercolors of Greek landscapes in the possession of the Gennadius Library of ASCSA], and perhaps also the Manship bronze.” [On this sculpture by Paul Manship, see “To deaccession, or not to deaccession?” Paul Manship’s Actaeon and the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.”] In the preface to his autobiography (I’ve Seen the Best of It) Alsop wrote that, when his doctor informed him that he had lung cancer, he was not surprised. He had been smoking 90 cigarettes a day!

It was a trip to Greece in 1963 that marked the genesis of The New Yorker article, From the Silent Earth, and Alsop’s service to ASCSA. He had sent a telegram in advance but, when he knocked on Blegen’s door at 9 Plutarchou St., he carried no letters of introduction. In The New Yorker he later wrote: “Having followed from afar the story that culminated in Pylos, I was […] eager to know Professor Blegen, and the chance presented itself when a holiday took me to Athens not long ago. After much worrying about being a nuisance, I decided to risk a telephone call to the Professor. When I boldly rang him up, he turned out to be one of those rare scholars […] who are pleased when outsiders show serious interest in their subjects.”

Blegen admired Alsop, as Nektarios Karadimas has recently noted (“His Eyes Took on a Far Away Look When He Spoke of Pylos,” in Carl W. Blegen: Personal and Archaeological Narratives [Lockwood Press, 2015]). In fact, after reading a draft of his contribution to The New Yorker, Blegen acknowledged: “The manuscript of your article on Pylos arrived yesterday and I have read it with great interest. It is very good indeed—though much too flattering about me—and I envy you your deftness in writing. It would have been very helpful to an archaeologist like me. I see that you have done a great deal of homework.” The two men quickly bonded and continued to correspond until 1966.

Alsop was, in fact, the right sort of man to convince Blegen of the genuineness of his mission. He brought with him to Greece a solid background in the Humanities, the result of his education at the Groton School and Harvard College. He was a man enthralled by the past, and his political analysis in “Matter of Fact” often referenced ancient events that he considered relevant in modern society.

For example, in a 1961 column about Kennedy and Khrushchev’s Vienna conference he recalled a Persian helmet at Olympia and the Battle of Marathon – the Cold War was yet another struggle between a slave empire and a free society. In 1962 he compared the Spartan-Athenian conflict on Sphakteria to “the scale of history in our bomb age.” A story from 1965, “The Cadmeion,” concluded that the foundations of the Mycenaean palace at Thebes are a “sly reminder that it is dangerous to be both rich and flabby – delivering a caveat just as America escalated its involvement in Vietnam. Alsop, in fact, never stopped drawing historical parallels to current events, even as he approached retirement. In one of his last syndicated columns (1974), he argued that “the balance of power is the nearly automatic mainspring of history,” and “an excessively unfavorable tilt of the balance of power is almost always fatal in the end.” He there adduced the battle of Cynoscephalae (197 B.C.) and the victory of Titus Quinctius Flamininus!

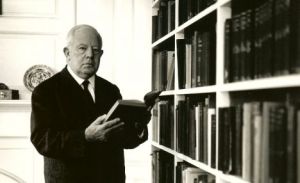

Alsop was also an art historian and an art collector. His masterful The Rare Art Traditions: The History of Art Collecting and Its Linked Phenomena Wherever These Have Appeared (1982) was based on his inaugural Mellon lectures in the new wing of the National Gallery of Art (1978). Ernst Gombrich (The New York Review of Books, December 2, 1982) called The Rare Art Traditions a “learned but lively tome” and “the first scholarly history of art collecting.” “The Rare Art Traditions” (China, Japan, ancient Greek and Rome, the Islamic states, and Western societies since the dawn of the Italian Renaissance) were so called because for Alsop they were the rare exceptions that did not follow the rule, in that they represented artistic creation as an activity divorced from practical use and one prized by the collector. In his eyes, it thus was the art collector who blazed the trail that led to our modern conception of art for art’s sake.

Alsop was also an art historian and an art collector. His masterful The Rare Art Traditions: The History of Art Collecting and Its Linked Phenomena Wherever These Have Appeared (1982) was based on his inaugural Mellon lectures in the new wing of the National Gallery of Art (1978). Ernst Gombrich (The New York Review of Books, December 2, 1982) called The Rare Art Traditions a “learned but lively tome” and “the first scholarly history of art collecting.” “The Rare Art Traditions” (China, Japan, ancient Greek and Rome, the Islamic states, and Western societies since the dawn of the Italian Renaissance) were so called because for Alsop they were the rare exceptions that did not follow the rule, in that they represented artistic creation as an activity divorced from practical use and one prized by the collector. In his eyes, it thus was the art collector who blazed the trail that led to our modern conception of art for art’s sake.

The antique and the august permeated Alsop’s home (Architectural Digest, October 1978): “from the gallery of family portraits tracing seven generations, in the dining room, to pictures of his ancestral homes, in the dressing room, to memorabilia of his own life, in the study. These personal artifacts are intermingled with eighteenth-century furnishings and a number of antiquities dating back to the third century B.C.” Collections included French 18th century embroideries, Burmese lacquer bowls, and panels of Japanese and Chinese textiles. He had bought a small Hellenistic figure in Paris while “kept waiting to see General de Gaulle.”

From the Silent Earth, like an Alsop newspaper essay, was a serious undertaking, part research, part journalism, and was grounded in global interests, catholic knowledge, and passion. He had always prided himself in getting the story before it became a story, gathering “facts” by direct contact with the newsmakers themselves. His syndicated columns were not simple opinion columns. In 1974 he wrote: ‘I do have strong opinions, but I do try to give the customers value for money – which are the facts on which my opinions are based.” This very principle guided him in writing From the Silent Earth, but he had a second objective.

Alsop wanted to make a personal contribution to the field of Greek Bronze Age archaeology, leaving his amateur status behind to “go pro,” in the words of The Washington Post’s reviewer (“Amateurs Dig to the Rescue: Pundit Alsop Joins Archaeology Novices in Helping the Pros Unearth Bronze Age Facts,” March 1, 1964). He believed he could accomplish that goal, however much he worried that professionals would not accept his conclusions. The importance of From the Silent Earth lies precisely in these conclusions —sometimes “on the money,” other times off the mark, but consistently provocative.

Key episodes in the Greek Bronze Age were to his mind only comprehensible as reflections of more generalized historical processes. In the final, and most original, chapter of From the Silent Earth Alsop’s own voice presides over a flurry of opinions culled from professional informants. He had set out the facts, and it was time to bring his unique analytical perspectives to bear — as he did regularly in “Matter of Fact.” He writes: “Archaeologists, and even historians specialized in periods for which archaeology provides the main evidence, quite often share a common human failing. … they tend not to allow for the diversity, the complexity and the peculiarity of all political processes.” He cautions against “drawing superficially logical conclusions from objects alone” and regrets that “the dominant political processes of the Greek Bronze Age have never been analyzed … simply as processes.”

How had the specialized world of the Mycenaean palaces emerged from a simpler, warrior society? For Alsop the Mycenaean Greek conquest of Crete was pivotal: Why and when did Greek come to serve as an administrative language at Knossos? He argues that, in the case of Mycenaeans on Crete, one historical scenario was most likely: “A warrior minority that seizes control of a more advanced society is like a child who suddenly gains possession of a costly, complicated piece of machinery, needing operating skills quite outside the child’s experience.” The conquerors may choose either to smash the machine or learn how to operate it. In the latter case, the minority will “grow up to be very like its teachers.” Conquests of “more advanced societies by warrior minorities must be considered as historical episodes of a specific sort with their own inherent tendencies and probabilities.”

So much for Alsop’s published prehistory of Greece, From the Silent Earth. In Part II of my contribution to this blog, we will burrow behind the printed text into archival records. For, in the course of researching Alsop’s cultural legacy, I made an unexpected discovery: although his principal archive is curated in the Library of Congress, the University of Cincinnati Archives and Rare Book Library contains five boxes of manuscripts, as well as correspondence about From the Silent Earth. The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star for October 12, 1964 proudly announced Alsop’s presentation of this archive to the University of Cincinnati in gratitude for Blegen’s kindnesses to him. It was then forgotten and, so far as I know, I am the first person to have examined the contents of the boxes since 1964.

So much for Alsop’s published prehistory of Greece, From the Silent Earth. In Part II of my contribution to this blog, we will burrow behind the printed text into archival records. For, in the course of researching Alsop’s cultural legacy, I made an unexpected discovery: although his principal archive is curated in the Library of Congress, the University of Cincinnati Archives and Rare Book Library contains five boxes of manuscripts, as well as correspondence about From the Silent Earth. The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star for October 12, 1964 proudly announced Alsop’s presentation of this archive to the University of Cincinnati in gratitude for Blegen’s kindnesses to him. It was then forgotten and, so far as I know, I am the first person to have examined the contents of the boxes since 1964.