By Sydney Vollmer, ARB student assistant

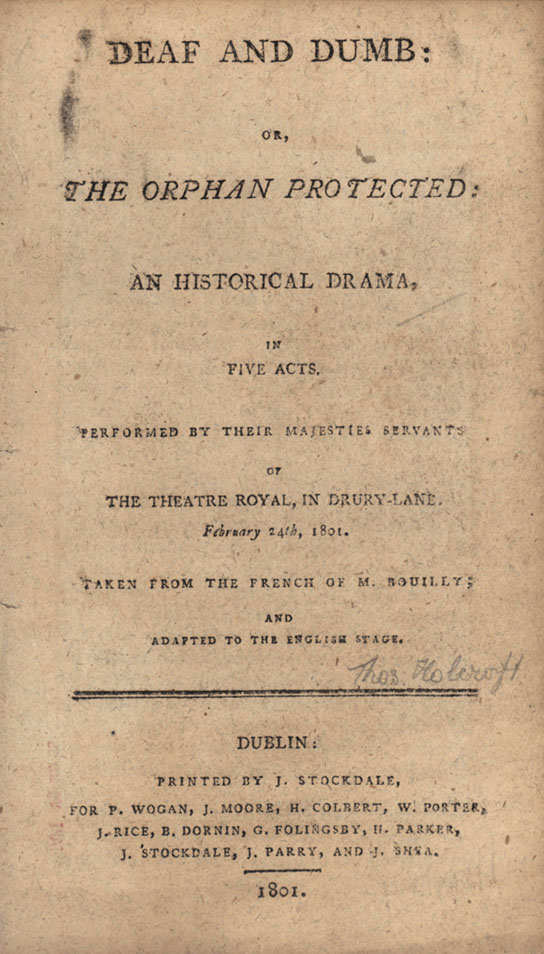

Here at the Archives and are Books library, we have a vast collection of 18th and 19th c. plays and I have been fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to read a play from our Irish subset of these holdings. Though we have numerous titles which grabbed my attention, I came across one that I couldn’t ignore: Deaf and Dumb, translated by Thomas Holcroft and published in Dublin in 1801.

Here at the Archives and are Books library, we have a vast collection of 18th and 19th c. plays and I have been fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to read a play from our Irish subset of these holdings. Though we have numerous titles which grabbed my attention, I came across one that I couldn’t ignore: Deaf and Dumb, translated by Thomas Holcroft and published in Dublin in 1801.

The title struck my interest because last summer, I began watching a TV show called Switched at Birth. One of the main characters in the show is Deaf, so there is a lot of sign language as well as the juxtaposition between the hearing and deaf worlds. Before watching the show, the obstacles Deaf people face and the idea of Deaf culture had never occurred to me.

Wanting to learn more, I signed up for American Sign Language (ASL) fall semester of this year. I fell in love with the language and began learning about the culture. One of the first topics we covered was how Deaf people have been viewed over the years. Up until fairly recently, Deaf people have been regarded as disabled, stupid, and less human, simply because they can’t hear and their speech is either impaired or they choose not to speak.

Knowing a basic outline of the world’s opinions of Deaf people, I took the opportunity to explore further. First of all, I didn’t realize that people would create a theatrical work around such an issue in that time. To explain the second item, I must give you a brief synopsis of the work:

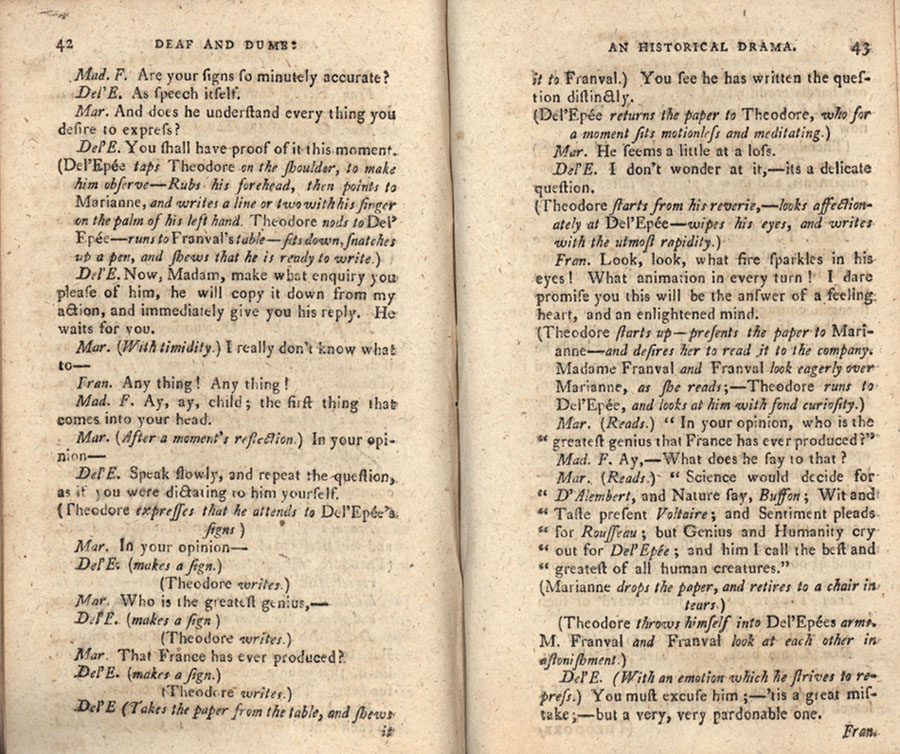

A man named Darlemont had been granted custody over his nephew, Son of the Count. His nephew was “Deaf and Dumb”. Not wanting to deal with this burden, and being greedy, Darlemont took his nephew to Paris and abandoned him, only to forge his nephew’s death upon return and take the fortune for himself and his own son. Eight years pass and the nephew, Theodore, returns with his instructor to relocate and repossess his house and fortune. Ultimately, Theodore’s wishes are granted and it’s a happy ending for everyone involved.

Del’Epee, Theodore’s teacher astounded me. Everyone assumed Theodore was stupid and couldn’t converse. Del’Epee knew this wasn’t the case, as he specialized in teaching the “Deaf and Dumb” how to communicate. He realized Theodore was especially intelligent, so he taught him how to communicate through signs. By communicating with him around other people, everyone soon realized that they were mistaken in believing Theodore to be stupid. This left me with the question of: If people in 1801 were able to conceptualize the inaccuracy of the phrase “Deaf and Dumb”, why has it taken so long for the fact to be accepted in society as a whole?

Societal issues aside, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this play. I thought that it was very well-written, organized, exciting, and the plot moved along at a good pace. At the very end, it wrapped up a little too quickly and happily, but these endings were to be expected during this time. As someone who thoroughly enjoys reading, writing, and performing, I am looking forward to absorbing as much of this collection as I can. To learn more about the Irish literature holdings of the Archives & Rare Books Library, visit our online exhibit at http://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/exhibits/irish-lit/, email us at archives@ucmail.uc.edu, or call 513.556.1959.