By: Sydney Vollmer, ARB Intern

As mentioned in a previous blog post on the fairy tales in the Archives & Rare Books Library, this blog is about the illustrator of In Powder and Crinoline and many other tales, Kay (pronounced “Kigh”) Nielsen.

As mentioned in a previous blog post on the fairy tales in the Archives & Rare Books Library, this blog is about the illustrator of In Powder and Crinoline and many other tales, Kay (pronounced “Kigh”) Nielsen.

Born on March 12, 1886 in Copenhagen, Denmark, Kay was the son of two actors. His father, Martinus Nielsen, directed the Dagmarteater and his mother, Oda, was highly praised for her work both in the Dagmarteater and the Royal Danish Theater. Despite his parents’ high standing in the theatre community, Nielsen found his passion in a different art form. He studied in Paris from 1904-1911 at Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi and after he received his education, he moved to England for five years. It was during that time he received his first commissioned work as an illustrator.

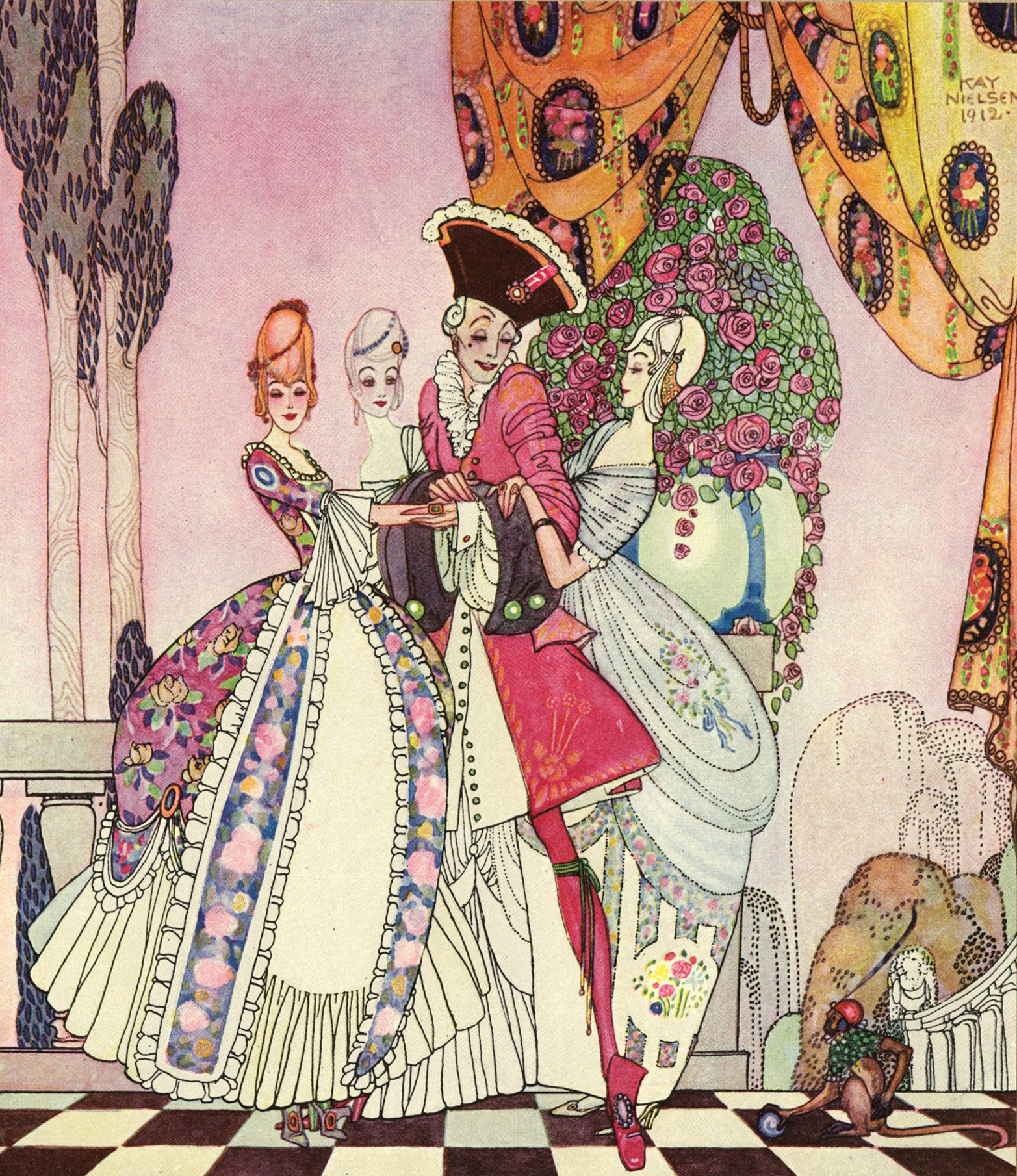

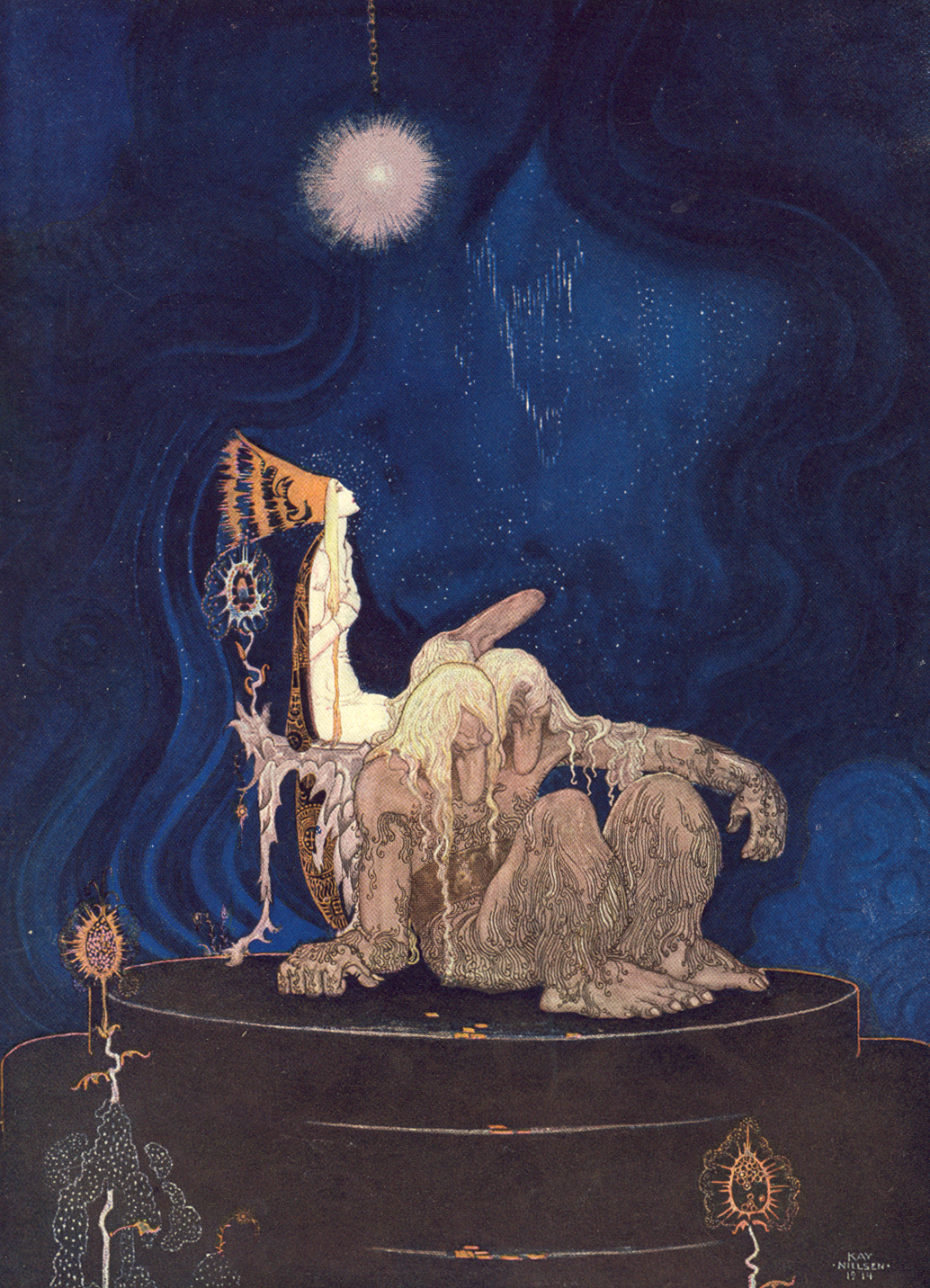

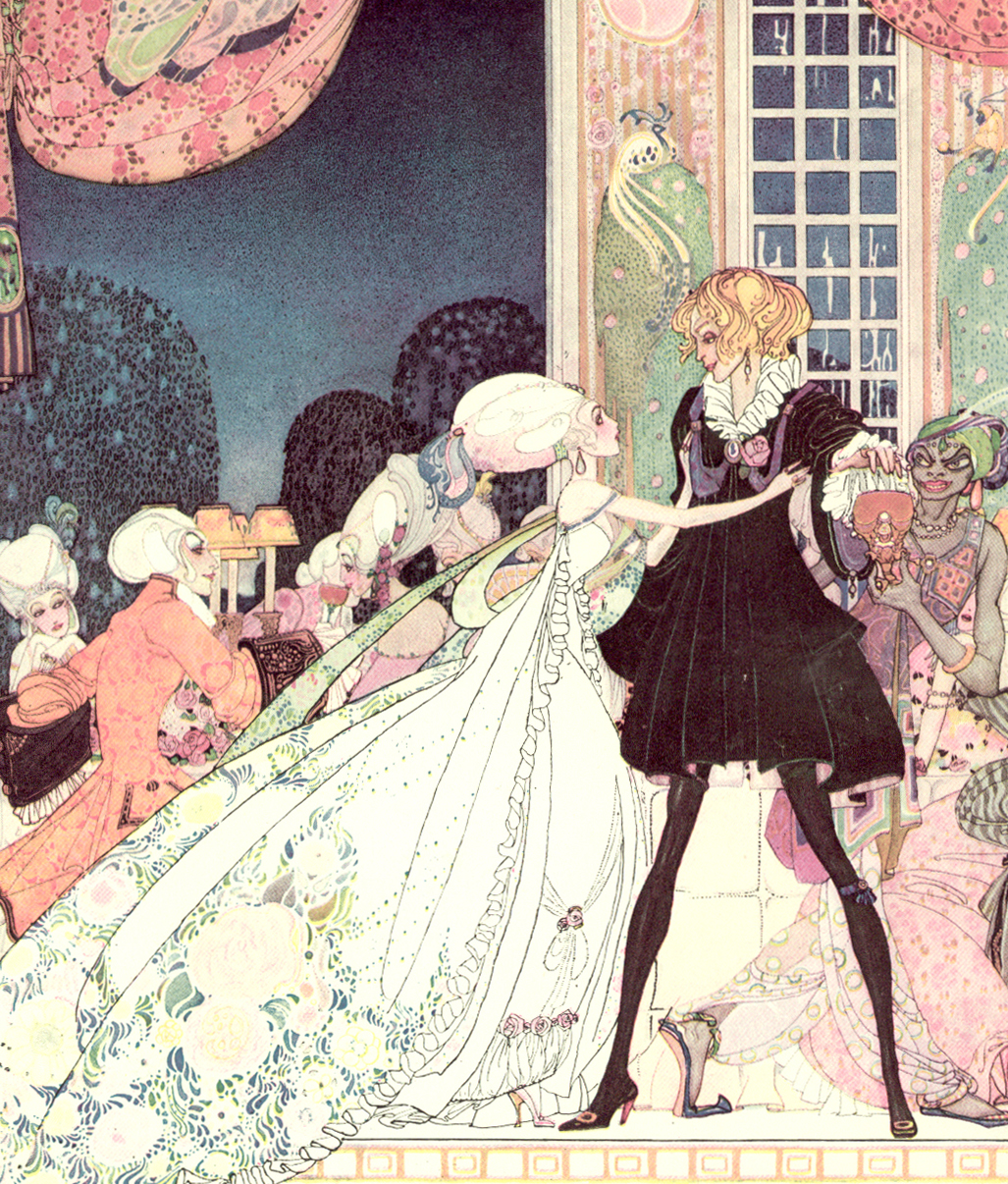

The publisher Hodder and Stoughton hired Nielsen to work on In Powder and Crinoline which was to be issued in 1913. That same year, The Illustrated London News commissioned him to create four illustrations for Charles Perrault’s works, Sleeping Beauty, Puss in Boots, Cinderella, and Bluebeard. A year later, Nielsen wowed the world by being of the first to introduce the four color process in the reproductions of his works. This method used color separations of cyan (blue), magenta (red), yellow, and black, or “cmyk.” Up until then, all other artists were using the three color process of filters, which was developed in the mid-nineteenth century. But Nielsen’s new work had more sumptuous and vibrant colors which proved to be very attractive to readers, and which carried the nature of fairy tales quite effectively. His debut using this printing mechanism was in what may be his most critically acclaimed book, East of the Sun, West of the Moon, a classic gathering of Scandinavian folk tales. This collection of stories contains titles such as its namesake, as well as “The Blue Belt,” “The Giant Who Had No Heart in His Body,” “One’s Own Children are Always Prettiest”, and more. During the time of this work, Nielsen had also produced a few scenes depicting the life and struggles of Joan of Arc as well painted landscapes in Dover. In Dover, he was introduced to The Society of Tempera which taught him how to reduce time in the printing process.

By 1917, Nielsen began receiving some well-merited recognition. He was invited to New York to mount an exhibition of his work. At the end of the show, he returned to Denmark where he painted scenery for the Royal Danish Theater for actor and director Johannes Poulsen. He worked on other illustrations during this time, but some of these were not found until years after his death—such as his illustrations for Scheherazade’s Arabian Nights.

The year 1924 brought renewed prosperity for Nielsen as he was asked to work on a new edition of Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen and a year later, in a fresh translation of the folktales gathered by the Brothers Grimm, Nielsen brought to life the world of Hansel and Gretel. In 1930, he added another title to his resume—Red Magic. At the end of that decade, he made the move to Los Angeles California where he tried his hand at working for Walt Disney in his animation studio.

Although his work is featured in Disney’s Ave Maria and the “Night on the Bare Mountain” sequence of Fantasia, Nielsen’s time at Disney was ultimately unsuccessful. As you can see by looking at his illustrations, he paid excruciating attention to detail. He also worked with soft pastels. The hard lines and fast pace of the Walt Disney Company did not treat him kindly. After only two years with the company, Nielsen was let go in 1941, although his name was given credit many decades later when The Little Mermaid premiered in 1989. He had done concept work on the tale taken from the work of his fellow Dane, Andersen, but the project had been indefinitely delayed.

Broken-hearted, he returned to his home in Denmark. But unfortunately, it seemed that his motherland didn’t want his work there either. As bad luck would have it, this was also when he contracted a chronic cough that stayed with him until his death. Eventually, Nielsen made his way back to Los Angeles where he obtained work painting a select few murals for schools and churches. On June 21, 1957, Kay Nielsen died. Before her death the following year, Nielsen’s widow, Ulla, gave his drawings to the artist and architect, Frederick Monhoff, who tried to place them in museums. Sadly, none took him up on his offer and it would be many years before Kay Nielsen’s work would be appreciated to its beauty and artistic craftsmanship. Now, his works are difficult to come by, and expensive when they are found.

Broken-hearted, he returned to his home in Denmark. But unfortunately, it seemed that his motherland didn’t want his work there either. As bad luck would have it, this was also when he contracted a chronic cough that stayed with him until his death. Eventually, Nielsen made his way back to Los Angeles where he obtained work painting a select few murals for schools and churches. On June 21, 1957, Kay Nielsen died. Before her death the following year, Nielsen’s widow, Ulla, gave his drawings to the artist and architect, Frederick Monhoff, who tried to place them in museums. Sadly, none took him up on his offer and it would be many years before Kay Nielsen’s work would be appreciated to its beauty and artistic craftsmanship. Now, his works are difficult to come by, and expensive when they are found.

The Archives and Rare Books Library holds many of Nielsen’s illustrations in books that you can experience for the asking, along with a bounty of other illustrated fairy tale volumes. We are located on the 8th floor of Carl Blegen Library, open from 8:00 am-5:00 pm, Monday through Friday. You may also contact us by email at archives@ucmail.uc.edu, callus at 513.556.1959, check out our website at http://www.libraries.uc.edu/arb.html, or find us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/ArchivesRareBooksLibraryUniversityOfCincinnati.

The Archives and Rare Books Library holds many of Nielsen’s illustrations in books that you can experience for the asking, along with a bounty of other illustrated fairy tale volumes. We are located on the 8th floor of Carl Blegen Library, open from 8:00 am-5:00 pm, Monday through Friday. You may also contact us by email at archives@ucmail.uc.edu, callus at 513.556.1959, check out our website at http://www.libraries.uc.edu/arb.html, or find us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/ArchivesRareBooksLibraryUniversityOfCincinnati.