By: Kevin Grace

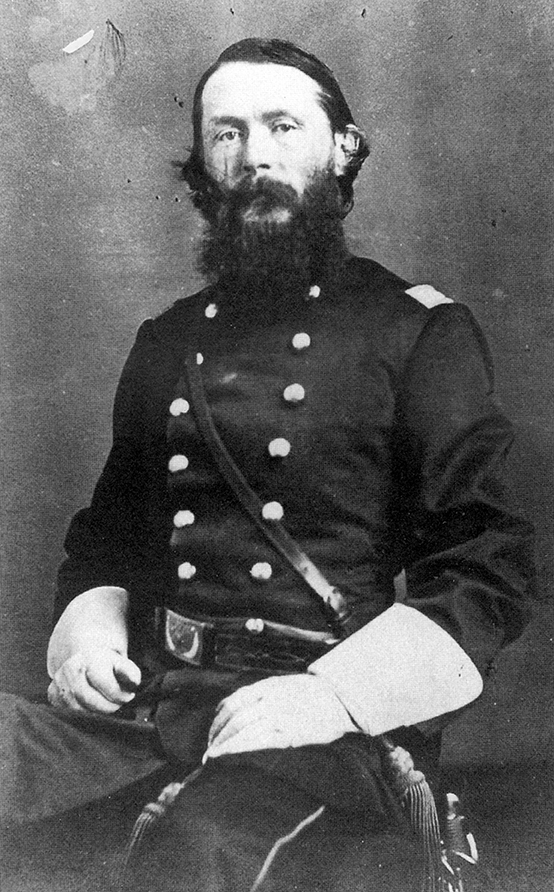

On September 20, 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, General William Haines Lytle of Cincinnati was shot and killed by a Confederate sniper’s bullet in the Battle of Chickamauga. A few days later, his body was carried back to his hometown. Lytle’s funeral was held at Christ Church Cathedral in downtown Cincinnati and the thousands of mourners followed his casket in the cortege to Spring Grove Cemetery, miles away from the church. The slow procession took up most of the day, the general’s body not arriving at Spring Grove until dusk. Sometime later, his grave marker – a broken column – would dominate the landscape of the garden cemetery.

On September 20, 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, General William Haines Lytle of Cincinnati was shot and killed by a Confederate sniper’s bullet in the Battle of Chickamauga. A few days later, his body was carried back to his hometown. Lytle’s funeral was held at Christ Church Cathedral in downtown Cincinnati and the thousands of mourners followed his casket in the cortege to Spring Grove Cemetery, miles away from the church. The slow procession took up most of the day, the general’s body not arriving at Spring Grove until dusk. Sometime later, his grave marker – a broken column – would dominate the landscape of the garden cemetery.

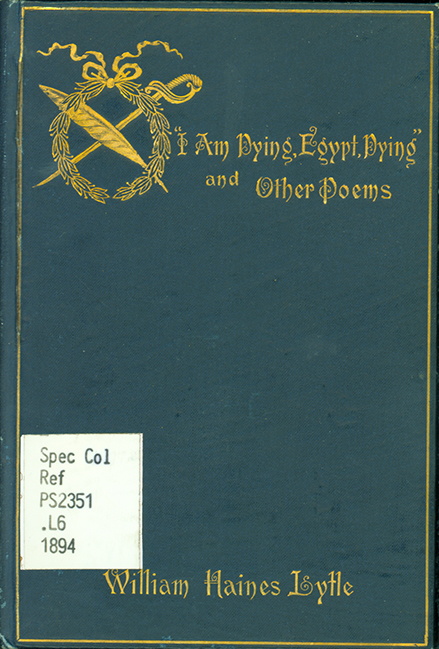

William Lytle was more than another officer killed in battle. He was a literary man, a soldier-poet whose verse in antebellum America was popular in both the North and the South, and whose lines reflected his experiences on the battlefield. They showed a view of the bloody vista typical of the Romantic era and they embodied his view of duty as well, in his eyes, a terrible beauty of death and destruction. Lytle was a part of the Romantic tradition in his poetry, incorporating his classical education as a boy with his notions of heroism and duty in life. This is an excerpt from a poem he wrote in 1840 as a fourteen-year-old, “The Soldier’s Death”:

“Early in the morning we found him lying cold and stiff on the scene of his former exploits”

The night had come and the stars were bright,

And the moon shone o’er the battlefield,

When the unjust cause of a tyrant’s might

Was crushed by the weight of freedom’s shield…

Upon the waste so stained with blood,

Beside a great and rushing stream,

A worn and weary soldier stood,

Like a phantom raised in a feverish dream…

When mortals by the wayside passed,

The soldier’s last deep breath had flown,

With naught to cheer save the midnight blast,

On the battlefield had he died – alone.”

Lytle was born in 1826 in a prominent Cincinnati family and educated at Cincinnati College, to which the University of Cincinnati traces its heritage to 1819. He later studied for the law and established a practice in the city. But during his early legal career, Lytle maintained a sense of wonder about the world and a desire to achieve satisfaction on the battlefield because he was enamored of the concept of “heroic death.” His life, he felt, should emulate that of Greek heroes and Shakespearean warriors. When the Mexican-American War broke out in 1846, Lytle enlisted in the 2nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry and served as a captain. During the conflict, he continued his writing, constructing poetry in the notion of a heroic vein. Here are verses from his image of one battle during that war, “The Siege of Chapultepec”:

Lytle was born in 1826 in a prominent Cincinnati family and educated at Cincinnati College, to which the University of Cincinnati traces its heritage to 1819. He later studied for the law and established a practice in the city. But during his early legal career, Lytle maintained a sense of wonder about the world and a desire to achieve satisfaction on the battlefield because he was enamored of the concept of “heroic death.” His life, he felt, should emulate that of Greek heroes and Shakespearean warriors. When the Mexican-American War broke out in 1846, Lytle enlisted in the 2nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry and served as a captain. During the conflict, he continued his writing, constructing poetry in the notion of a heroic vein. Here are verses from his image of one battle during that war, “The Siege of Chapultepec”:

Wide o’er the valley the pennons are fluttering,

War’s sullen story the deep guns are muttering,

Forward! blue-jackets in good steady order,

Strike for the fame of your good northern border;

Forever shall history tell of the bloody check

Waiting the foe at the siege of Chapultepec…

…Death revels high in the midst of the bloody sport…

And on one general, T.L. Hamer:

The brave who sleep in glory’s shroud,

How proud a fate is theirs!

After he returned from Mexico, Lytle built up his law practice and was elected to the Ohio state legislature. But his poetry now became his passion and as he published more of it in anthologies and newspapers, he became quite popular on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. This popularity would realize a significance in his eventual death.

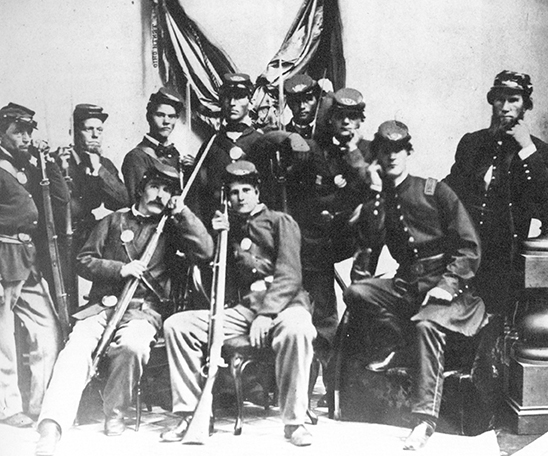

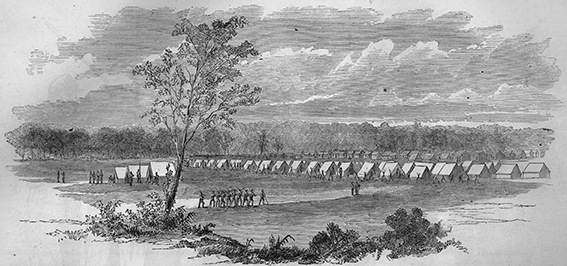

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, William Lytle was commissioned as a colonel in the 10th Ohio Volunteer Regiment, a regiment composed primarily of working-class Irish in Cincinnati. His troops mustered in nearby Camp Dennison and soon they were dispatched to the Virginia battlefields. The regiment became known, in a tip to an Irish brogue, as “the Bloody Tinth” for its actions. In his article, “Civil War Imagery, Song, and Poetics: The Aesthetics of Sentiment, Grief, and Remembrance,” literary scholar Richard Leppert astutely attributed Civil War creative output to an awareness of and familiarity with the extensive photo documentation of the war that spoke of the tragedy of youthful death, the breaking familial bonds, and the sincerity of feeling. The sentimental and saccharine ballads and poems often were not critically received, but enjoyed immense popularity because of the emotional responses they invoked. For Lytle, whose verse had been widely recited before the war, his embracing of classical heroism and duty could be rendered as lamentations about the battlefield. This mindset of his was evident even in his letters home to his treasured sisters before he led his men into battle at Carnifex Ferry in Virginia in 1861:

My beloved Sisters,

It is very late at night but I could not sleep without writing to you. An engagement is

expected very soon – probably tomorrow. I am not at liberty to give particulars –

except that I heard tonight unofficially that my regiment would have the advance…

Good bye my darling sisters. I hope a merciful God may re-unite us in this world,

but if otherwise ordered let us hope to meet in a better…

During that battle, albeit a minor skirmish, Lytle’s men suffered many casualties, himself included when he took a bullet in his calf that resulted in a serious wound and sent him back home to Cincinnati for an extended recovery. When he returned to service, he again resumed a customary approach to a battlefield fate, expressed again in a letter to his sisters:

…I should try to do what is right & just & trust that our father whose shield has so

wonderfully protected me heretofore will direct my steps & give me strength to

endure everything. I often sigh for a life of calm & quiet but perhaps by bodily

weakness & lassitude have an effect on my spirits just now…

William Lytle’s letters were not dissimilar from that of thousands of other soldiers who were writing home to their loved ones, but he seemed to thrive in the style and the literary tradition he acutely knew he embodied in his writings. As he returned to fighting in Kentucky and Virginia, he penned this letter to one of his sisters:

Would be to God dear Sister this unhappy war were honorably terminated…And yet I

feel it my duty as long as I can to share with my generation its heavy burden and to

stand along side of my brave comrades in arms to the last gasp…In no nobler or holier

a cause can a man’s life be offered up…Farewell dear Bessie…

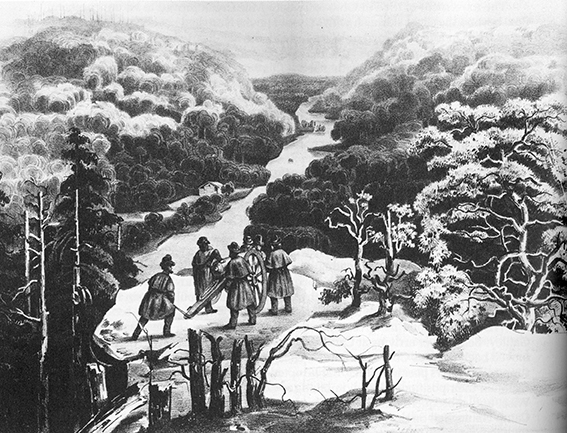

and this poem, “In Camp,” in 1862:

I gazed forth from my wintry tent

Upon the star-gemmed firmament…

I gazed, till to the sun the drums

Rolled at the dawn, “He comes, he comes.”

Though he held to the tropes of death, destruction, and devastation on the battlefields spread out before him, Lytle’s writing most often turned to himself in almost a narcissistic manner of how he –himself- answered the call or entered the fray – was he up to snuff as a Greek hero, was he executing his duty as a Roman centurion, was he mindful enough of his responsibility to his soldiers and to his family as an American, would he fall on the stage of bloody ground as well and as dignified in death as a Shakespeare tragedian?

The field of battle became his dramatic stage.

Lytle was wounded once more in the war. It was the second time, and though one might be tempted to read his verse as poetic posturing of a sort, in the view of his friends, family, and countrymen who read his poems with love and admiration, he was indeed courageous and never hesitant in putting himself in harm’s way as he led his troops across the fought-for fields and mountain passes. His promotion to brigadier general earned him more responsibility along with a heavy-hearted acceptance, and, perhaps appreciation of his own duty.

His time was coming. At Chickamauga Creek in Georgia, he led his troops in September 1863 in a counterattack against the Confederate line. Just days before, even though he had some time ago been reassigned to other regiments, the 10th Ohio Volunteer Regiment, his old troop of Irish fighters, presented him with a bejeweled Maltese cross for his leadership. In the counterattack, around mid-day the sniper’s bullet found him. Knowing who he was, the Rebel troops held his body and respectfully placed a guard around him for the night, quietly reciting his poetry to each other. In a brief truce the next day, Lytle’s corpse was carried to his Union troops and he was sent home for burial.

Lytle was mourned by both sides of the conflict, his battle poetry and verse of man against man – and man against fate – loved by both sides because in many ways the poems answered a need to be noble in life. There was a shared cultural background in this respect. His poetry was a reflection of popular form and subject. The blood and gore of the Civil War may have signaled the end of a reliance upon – and an education – in the Romantic form.

As those Confederate soldiers guarded Lytle’s body the night of his death, one of that poems that was read was one of his most well-known, a poem he wrote in 1858, “Antony and Cleopatra”:

…I am dying, Egypt, dying!

Hark! the insulting foeman’s cry;

They are coming; quick, my falchion!

Let me front them ere I die.

Ah, no more amid the battle

Shall my heart exulting swell;

Isis and Osiris guard thee, –

Cleopatra, Rome, farewell!