By: Kevin Grace

“For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.”

Those are the final lines in Romeo and Juliet. The young lovers are dead, victims of their own passion and the enmity between the Capulets and the Montagues. Though their story is set in Renaissance Verona, it could be a tale told in any culture around the world in any era of humankind. For all the literary genius of William Shakespeare, scholars have long known that many of his plays were re-workings of stories he heard and historical accounts he read during his lifetime. Whether it was for Hamlet, Macbeth, Richard III, Othello, or others, Shakespeare adapted these accounts for his stage in the late 16th and early 17th centuries that now have been performed countless times for more than 400 years, and over those centuries his own words have been adapted time and again. To see King Lear presented in England or Ireland is not the same as seeing it performed in South Africa or India or China. And of course, to see it once in England or America is not the same as seeing it once again on what might be the same stage in the same year. William Shakespeare’s plays are paragons of beautiful language, infinite interpretation, and above all, compelling stories.

Those are the final lines in Romeo and Juliet. The young lovers are dead, victims of their own passion and the enmity between the Capulets and the Montagues. Though their story is set in Renaissance Verona, it could be a tale told in any culture around the world in any era of humankind. For all the literary genius of William Shakespeare, scholars have long known that many of his plays were re-workings of stories he heard and historical accounts he read during his lifetime. Whether it was for Hamlet, Macbeth, Richard III, Othello, or others, Shakespeare adapted these accounts for his stage in the late 16th and early 17th centuries that now have been performed countless times for more than 400 years, and over those centuries his own words have been adapted time and again. To see King Lear presented in England or Ireland is not the same as seeing it performed in South Africa or India or China. And of course, to see it once in England or America is not the same as seeing it once again on what might be the same stage in the same year. William Shakespeare’s plays are paragons of beautiful language, infinite interpretation, and above all, compelling stories.

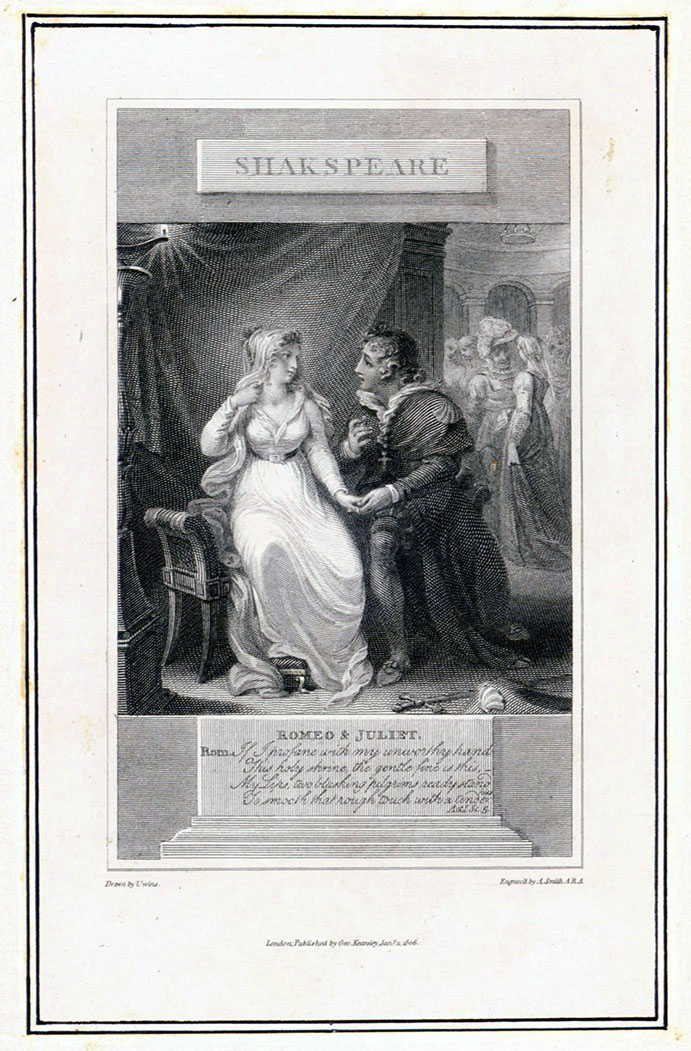

Tracing Shakespeare’s plays to the books and tales that inspired them is a fascinating endeavor, discovering the accounts from Italy or North Africa, or chronicles of ancient Rome and medieval Britain in order to understand how they would be adaptable to the stage and why they would find favor with his audiences. As creative an artist as he was, Shakespeare was also an astute businessman and impresario. He knew how to fill the theatres with groundlings and seat-sitters. Pennies in the box meant a profitable box office. And the plays have survived Shakespeare’s scripts since the era of the Globe and Blackfriars, published over and over again, illustrated edition after illustrated edition. The Archives & Rare Books Library holds an excellent collection of Shakespeare editions, mostly 18th and 19th century printings that were part of Cincinnatian Enoch Carson’s personal library. When William A. Procter purchased the library and presented it to the University of Cincinnati around 1900, Carson’s Shakespeare holdings were one of the university’s original collections of books.

Tracing Shakespeare’s plays to the books and tales that inspired them is a fascinating endeavor, discovering the accounts from Italy or North Africa, or chronicles of ancient Rome and medieval Britain in order to understand how they would be adaptable to the stage and why they would find favor with his audiences. As creative an artist as he was, Shakespeare was also an astute businessman and impresario. He knew how to fill the theatres with groundlings and seat-sitters. Pennies in the box meant a profitable box office. And the plays have survived Shakespeare’s scripts since the era of the Globe and Blackfriars, published over and over again, illustrated edition after illustrated edition. The Archives & Rare Books Library holds an excellent collection of Shakespeare editions, mostly 18th and 19th century printings that were part of Cincinnatian Enoch Carson’s personal library. When William A. Procter purchased the library and presented it to the University of Cincinnati around 1900, Carson’s Shakespeare holdings were one of the university’s original collections of books.

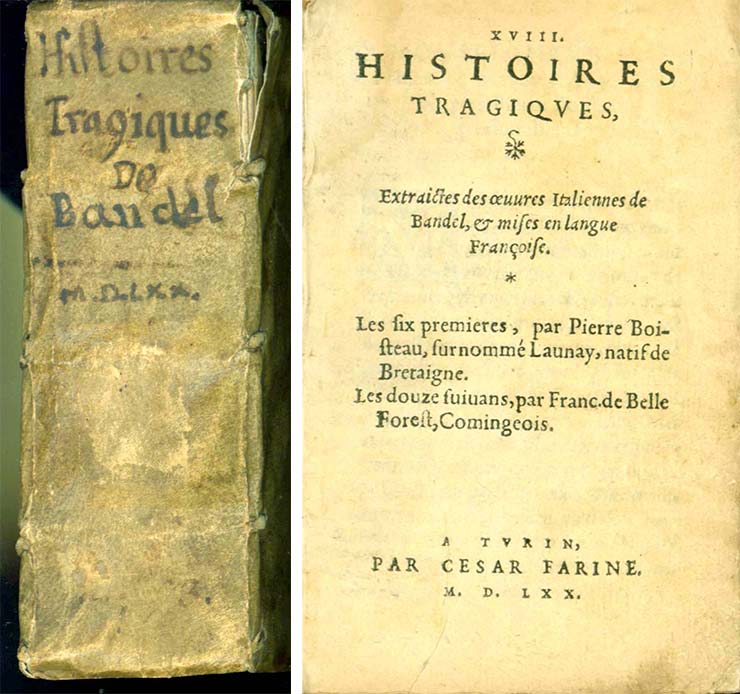

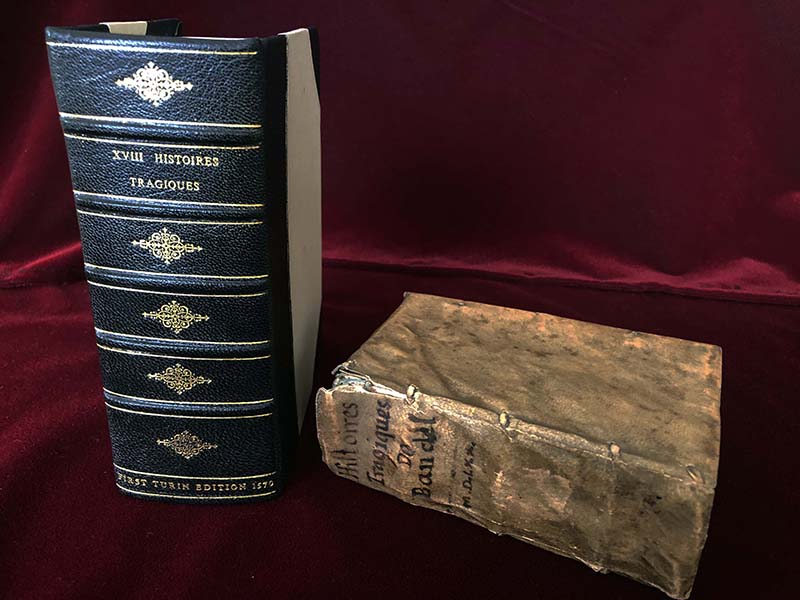

Over the past century, this collection has been augmented with further editions and printings, including books about Shakespeare and his world. A recent purchase adds even more importance to the volumes because it is considered to be a source for Shakespeare’s story of Romeo and Juliet. Printed in Turin, Italy, the book is XVIII histoires tragiqves / extraictes des œuures Italiennes de  Bandel, & mises en langue françoise ; les six premieres, par Pierre Boisteau, surnommé Launay, natif de Bretaigne. Les douze suiuans, par Franc. de Belle Forest, Comingeois by Matteo Bandello (1485-1561). First published in Lyon in 1560 and later in Paris in 1563 and 1564, this volume was issued in 1570 by printer Cesar Farine and is the fourth collected edition of fictional stories that are the source material for Romeo and Juliet. It is more rare than the earlier editions. Bound in full vellum with an inked title on the spine, only one other copy is recorded in libraries worldwide. And, copies of this edition have not been on the market in four decades. There are only two known copies of the 1564 edition, but what makes the University of Cincinnati’s copy even more special is that it is bound in a contemporary binding and is a vigesimo size (or, “20mo”), 5″ x 3″. That is, to see this book today, to hold it in the hand and study it, is to see it and read it as it was 448 years ago. It is what William Shakespeare would have read, considered the storyline of “star-crossed” lovers beset by feuding families, and then penned a love story for the ages.

Bandel, & mises en langue françoise ; les six premieres, par Pierre Boisteau, surnommé Launay, natif de Bretaigne. Les douze suiuans, par Franc. de Belle Forest, Comingeois by Matteo Bandello (1485-1561). First published in Lyon in 1560 and later in Paris in 1563 and 1564, this volume was issued in 1570 by printer Cesar Farine and is the fourth collected edition of fictional stories that are the source material for Romeo and Juliet. It is more rare than the earlier editions. Bound in full vellum with an inked title on the spine, only one other copy is recorded in libraries worldwide. And, copies of this edition have not been on the market in four decades. There are only two known copies of the 1564 edition, but what makes the University of Cincinnati’s copy even more special is that it is bound in a contemporary binding and is a vigesimo size (or, “20mo”), 5″ x 3″. That is, to see this book today, to hold it in the hand and study it, is to see it and read it as it was 448 years ago. It is what William Shakespeare would have read, considered the storyline of “star-crossed” lovers beset by feuding families, and then penned a love story for the ages.

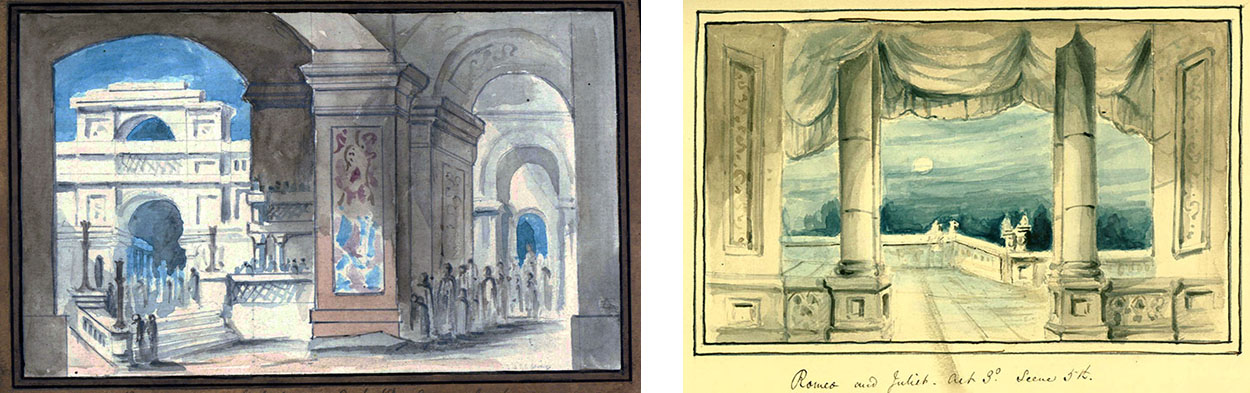

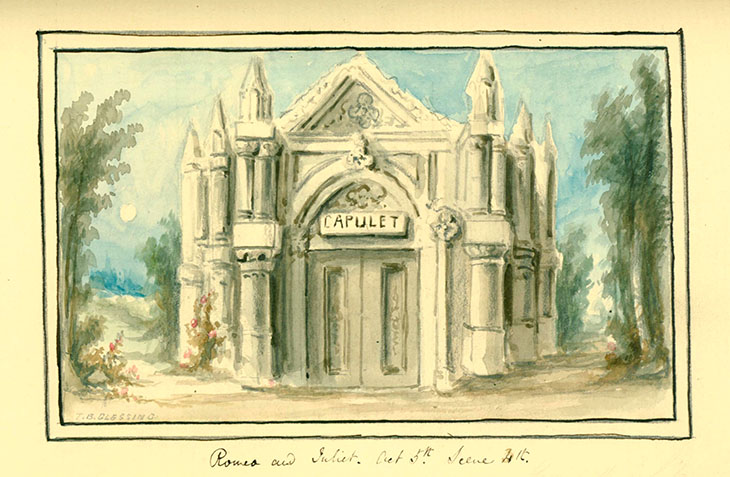

Bandello’s book is housed in the Archives & Rare Books Library, call number SpecCol RB PQ4606.A13 1570. close to the Shakespeare volumes. The accompanying illustrations here are from the Romeo and Juliet volume in the Procter-Carson extra-illustrated edition of 1900, call number SpecCol RB PR2753.K7 1839a, vol. 28.