The universities of Cincinnati and Michigan and all partner institutions in the “Greek Digital Journal Archive” (GDJA) program commemorate the 200-year anniversary of an independent Greek state.

Had it not been for the Covid-19 pandemic, the John Miller Burnam Classics Library would have celebrated this important occasion with talks, book exhibitions, Greek music, and Greek foods inside the physical library. As it is, this blog post will serve as a “poor” substitute. However, you will get to hear a conversation recorded for this blog with Associate Professor Alexander Christoforidis, Division of Experienced-based Learning and Career Education at the School of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning at the University of Cincinnati and the Director of the Greek School at the Holy Trinity-St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church in Cincinnati, along with links to information about the War, to songs detailing the fight for independence, as well as a book exhibition of scanned Classics Library journal and book pages, and photos of Greece, Greeks, Greek-Americans, Philhellenes, Greek foods, and Greek music. Try to picture the day when we can celebrate with each other in person! Until then, Happy Bicentennial Greeks, Hellenists, and Philhellenes!

Watch Greek TV live of a special Independence Day Parade on March 25 in front of Syntagma Square in Athens and listen to the historic narrative!

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution, was waged against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Revolution is celebrated by Greeks around the world on March 25 as Greek Independence Day. On that day this year, 2021, Greeks commemorate the 200-year anniversary of the official beginning of the Revolution leading to a new independent Greece after almost 400 years of Turkish rule.

A Conversation with Alexander Christoforidis —

about the Greek Revolution, the Greek School in Cincinnati, and the Greek Community in Cincinnati.

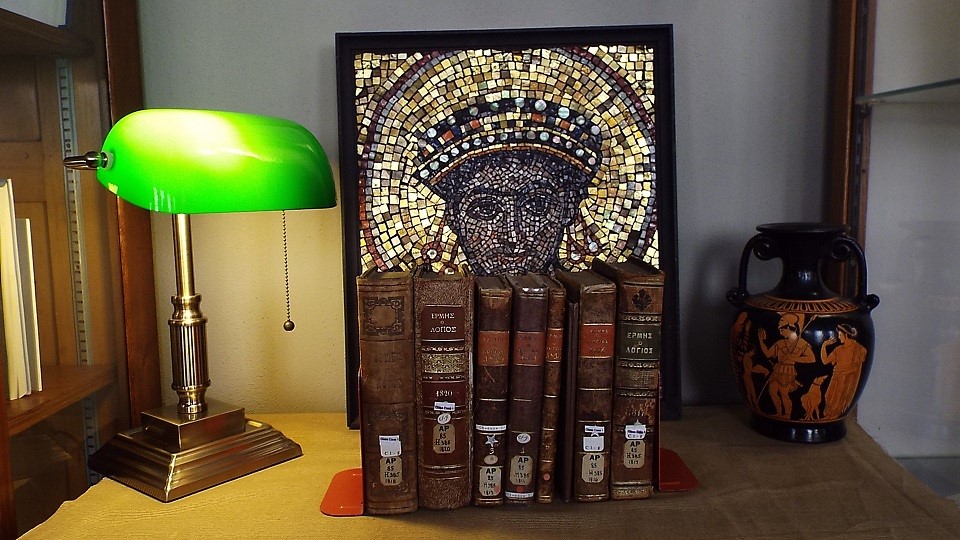

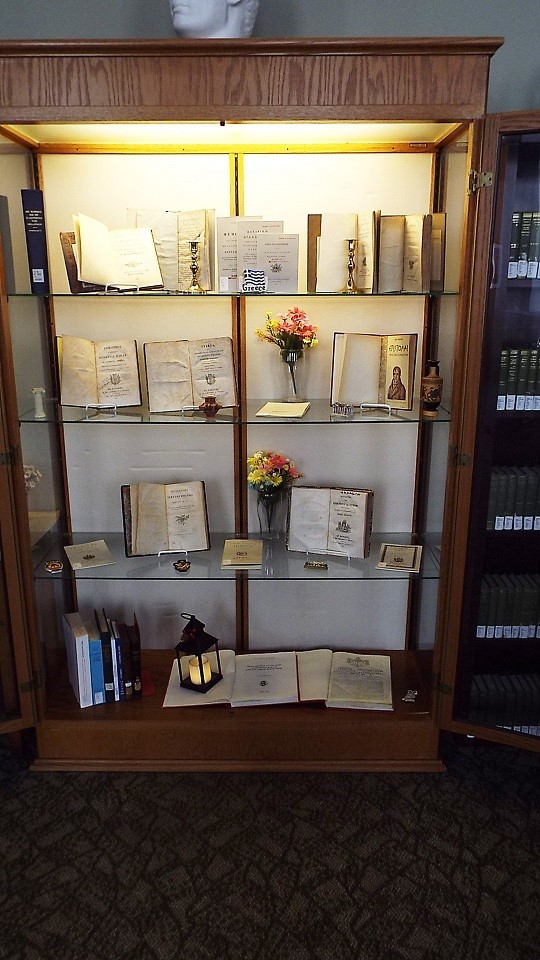

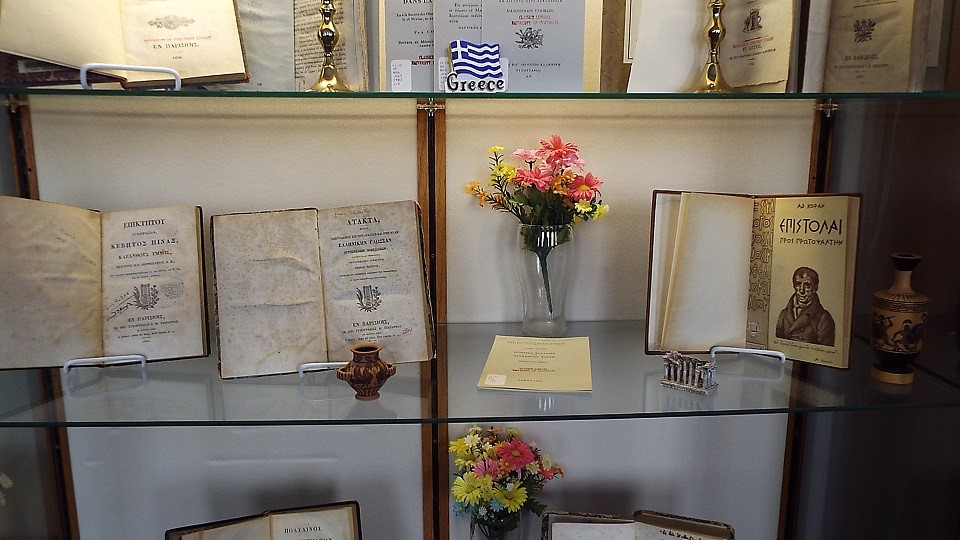

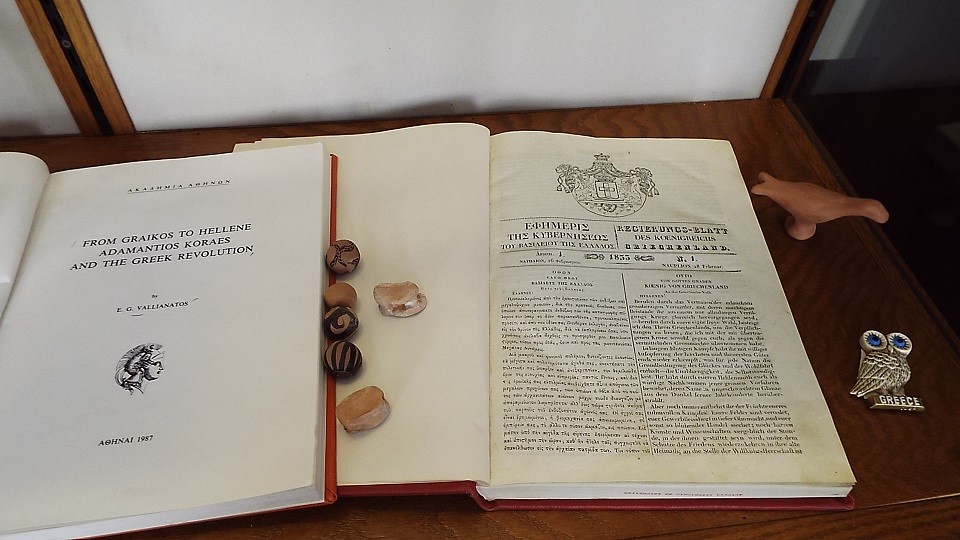

Book exhibition in the Burnam Classics Library commemorating the Greek War of Independence which began on March 25, 1821, 200 years ago.

In Odessa 1814, a secret organization calling itself Φιλική Εταιρεία (Filikē Etaireia) “Society of Friends” was formed with the aim of liberating Greece. The insurrection was planned for March 25, 1821, the Greek-Orthodox Feast of the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God.

The War was to last for almost ten years during which time many American intellectuals, cultural personalities and politicians, but also “regular” citizens supported the revolutionaries through fund-raising campaigns, poetry, letters, manifestoes and even through individuals leaving for Greece to fight in the battle for the Greek cause.

With the memory of the American Revolution in the not too distant past and an appreciation for the importance of ancient Greece for the institution of American democracy, republicanism, art and architecture, for example, the White House and the Capitol, the Church of the Annunciation and the PNC Tower in Cincinnati, philosophy, literature, for example, Homer, the tragedians, the lyric poets, and the many words in English derived from Greek, philhellenic sentiments ran high in the United States and Europe.

The Greek Cause in America

In May 1821, almost immediately after the outbreak of the Greek Revolution, the Messenian Senate of Kalamata addressed an appeal to the citizens of the United States requesting, in the name of liberty and Christianity, that assistance be given “to purge Greece from the barbarians, who for four hundred years have polluted the soil.” Also, the Greek rebels were after all only following the example of the American Revolution fifty years earlier. Greeks and Americans, they said, are by nature “friends, fellow citizens, and brethren.” The appeal was forwarded to the Greek committee in Paris, from where it was dispatched to the United States. Albert Gallatin mailed the Greek text and a French translation to John Quincy Adams from Paris in September of 1821, and at about the same time Adamantios Koraïs sent a copy to Edward Everett, professor of Greek at Harvard and editor of the North American Review. The document was printed and distributed throughout the United States and formed the basis for appeals on behalf of the Greek cause. President Monroe expressed sympathy with the Greek people, but did little in terms of actual aid. George Jarvis, a New Yorker, became the first person to actually join the Greek army. In 1823, interest in the Greek cause in the U.S. seems to have diminished somewhat as civil war broke out among the revolutionaries. However, once Lord Byron joined the Revolution, sentiments changed. Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to Greek philologist and academic revolutionary Adamantios Koraïs in Paris, congratulating him on his efforts to make available to the contemporary Greeks “the fine models of science left by their ancestors, to whom we are all indebted for the lights which originally led ourselves out of Gothic darkness.” Koraïs had made it his life’s work to educate his compatriots about their ancient Greek heritage. John Adams wrote to the Greek Committee in New York in December of 1823 that he would be glad to contribute his “might” to the war for independence. In New York, the campaign was launched by the erection of a huge cross in Brooklyn Heights, with the inscription “sacred to the Greek cause.” Merchants donated a percentage of their profits; objects of value were offered at public auctions and sold at inflated prices; school children gave pennies; laborers gave up a day’s wages; shipowners donated space on their ships for supplies destined for Greece; balls and fairs were held (Earle, p. 51). Most of the moneys raised went to ammunition and military equipment; only later to civilians. In spring of 1824, a group of young Americans left for Greece to offer their services to the Greek military. Foremost among these was Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe of Boston, then a young physician just out of Harvard, later a famous philanthropist and the husband of Julia Ward Howe. He was appointed surgeon-general in the Greek army and lobbied in America for funds for the civilian population, the distribution of which he oversaw.

“The Free and the Brave” Exhibition to Highlight American Philhellenism. This is a wonderful exhibition curated by Maria Georgopoulou of the Gennadius Library at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. This Library possesses an outstanding collection of Greek history materials, some of which are highlighted in this exhibition.

Greek fighters, not of this war but of wars more than 2,000 years ago. It is likely that European and American freedom fighters alike thought back to the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars.

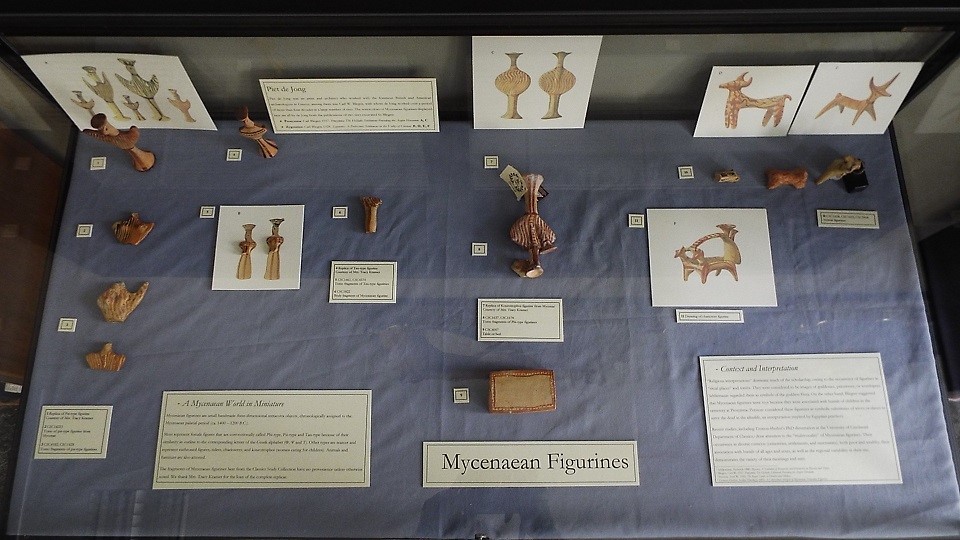

Original ancient Greek artifacts in the Burnam Classics Library. On loan from the University of Cincinnati Art Collection.

The earliest Greek, Mycenaean (ca. 1600-1100 BCE), artifacts from the UC Classics Department on display in the Burnam Classics Library.

Philhellenes in Cincinnati

“Grecian fever” reached not only the large cities on the East Coast such as New York and Boston, but also “as far west” as the newly founded and burgeoning city of Cincinnati. “Philhellenism reached as far as Cincinnati in the west and Calcutta in the east” (Lazos, p. 469). In the 1820’s, the city of only 12,000 inhabitants had several theaters, churches, and schools, and as many as six newspapers. In 1822-23 all of them reported on Greece and the uprising. Several had standing news columns entitled “Greece,” “The Greeks,” “News from Greece.” Many of the city’s most prominent citizens declared themselves Grecians and successful fund-raising events took place throughout Cincinnati to aid the revolutionaries.

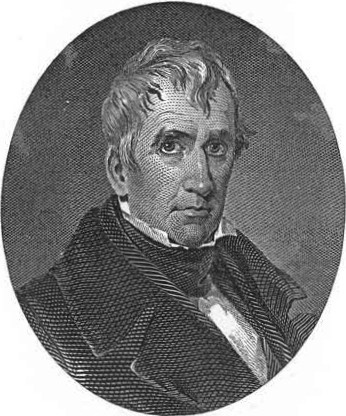

The two most fervent supporters of the Greek cause were Moses Dawson, the Irish editor of the Inquisitor and the Cincinnati Advertiser, and General William Henry Harrison, later the ninth President of the United States. Firemen, storekeepers, barbers, college students, just about everyone in Cincinnati seems to have supported the cause in words and even through monetary contributions. Farmers were asked to not only contribute money but also food products and regular citizens both money and clothing. On June 9 1821, Western Spy and Literary Cadet had reported on the Revolution for the first time in Cincinnati – “an insurrection has most certainly taken place among the Greeks.”

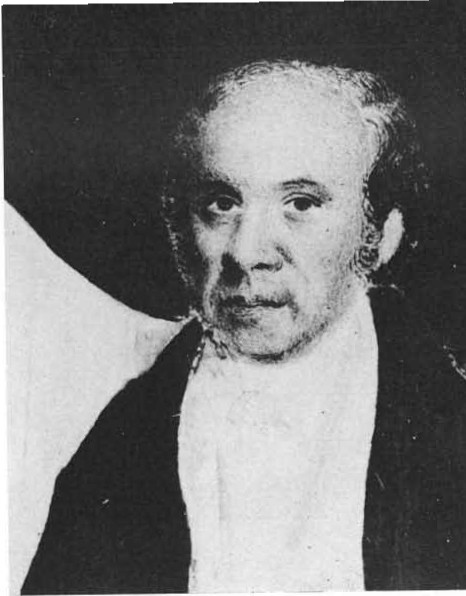

Moses Dawson (1768-1844)

After intense lobbying by Moses Dawson, the Euterpeian Society gave the first Greek benefit event in Cincinnati at the First Presbyterian Church on Mount Adams on January 23, 1824. The keynote speaker was Cincinnati’s most famous citizen at that time, General William Henry Harrison. The significant amount of more than 300 dollars was raised. The funds were forwarded to a secret organization of philhellenes in New York. The year 1824 was proclaimed “Χρονιά των Ελλήνων” (the Year of the Greeks) by Dawson. Dawson in his fervor for (ancient) Greece and the revolutionary Greeks encouraged the residents of Cincinnati to send their hard-earned money to “the Christian Greeks instead of to the Indians.” “If every man, woman, and child were to donate just one penny, $125,000 would be raised for the Greek cause” (Lazos, p. 472).

General William Henry Harrison (1773–1841)

There are not many buildings in Cincinnati still standing from before or during the years of the Greek War. The Taft Museum of Art on Pike Street, built in 1820, is one of the very few.

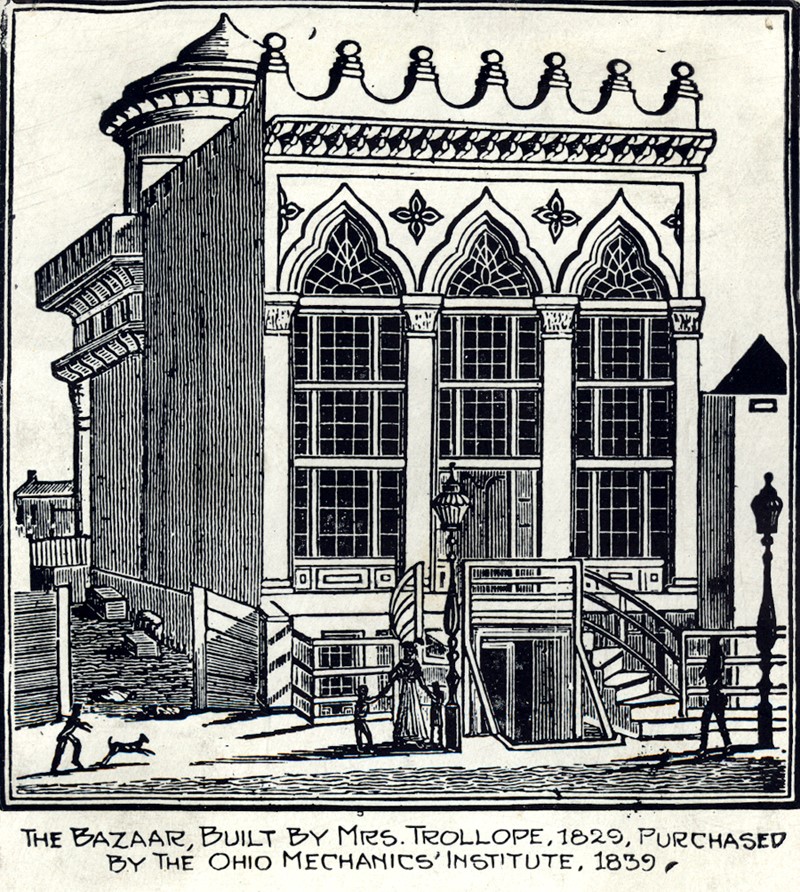

The Bazaar or “Trollope’s Folly” erected by Seneca Palmer in 1828-29 upon the direction of Frances Trollope, blended many architectural styles — Greek, Moorish, Egyptian and Gothic. Frances Trollope was a British philhellene who lived in Cincinnati for a few years and whose support for the Greek cause brought her into contact with another British philhellene, Jeremy Bentham, with whom she corresponded. The Bazaar housed a coffee house, ice cream parlor, exhibition galleries, and a ballroom. Regrettably, it was torn down in 1881. The Greek Revolution inspired interest also in ancient Greek architecture. The so called Greek Revival style flourished in Cincinnati after the Revolution, 1835-1860.

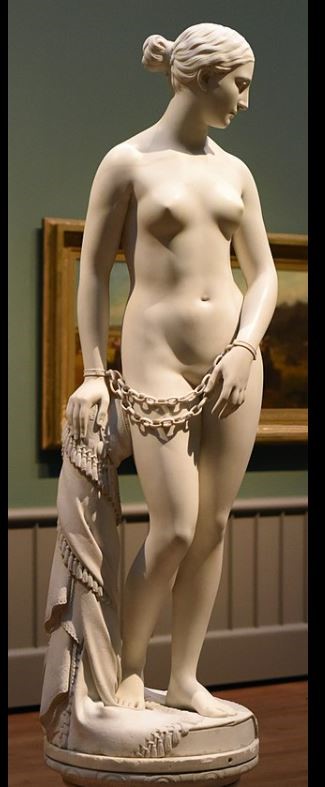

Another Cincinnati connection is the Cincinnati resident sculptor Hiram Powers and his “Greek Slave,” which may have been inspired by the story of Garyphallia/Garafilia, a little Greek girl of 7 who was taken prisoner by the Ottomans after they killed her parents and siblings. She eventually ended up being purchased at a bazaar at age 10 by American Joseph Langston who saved her and took her to Boston to live with his cousins. She was sent to school where she was a bright, sweet and obedient girl until she passed away at age 13 of tuberculosis. After the brutal treatment she had received while a slave and her long journey from the island of Psara to Turkish Smyrna (Izmir) without food or much clothing and the long trip to America, her little body was worn out. Powers depicted the Greek Slave, Garyphallia, in the image of Venus de Milo, 1844.

Russia, Britain, and France joined the war against the Turks in 1827, which ended with Greek independence through the Treaty of Adrianople on September 14, 1829. The initial territory of the Greek state comprised central Greece, the Peloponnese, and most of the Aegean islands. Greece had to wait another 100 years and the Balkan Wars to assume its current form. The Greek Revolution was a catalyst which encouraged other nations in south-east Europe to also rise up against the Ottomans.

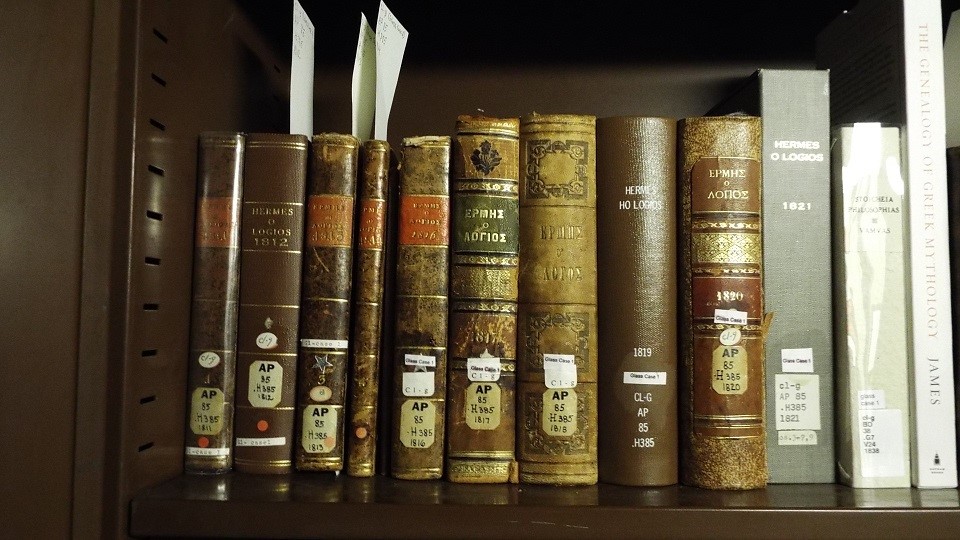

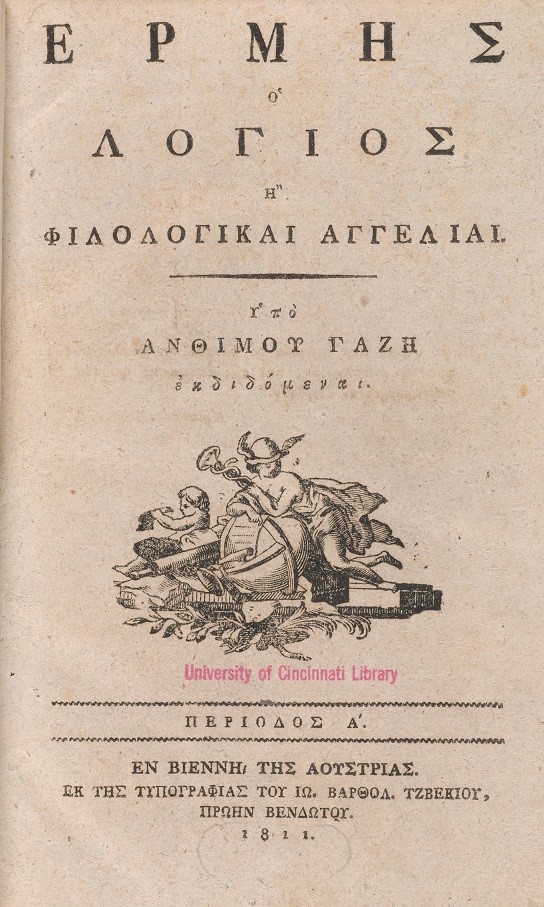

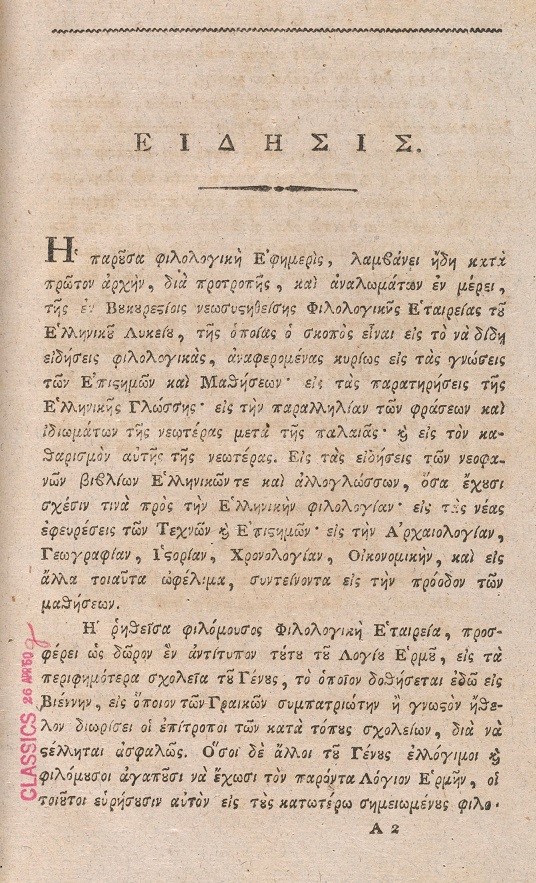

Έρμῆς ὁ λόγιος (Hermes ho Logios), the journal of Greek intellectuals dispersed throughout Europe during the pre-Revolutionary period and an important source for the theoretical background of the Revolution as well as the first journal published in Modern Greek (1811-1821). As it was not possible for the Greeks under the Ottomans to publish in Greece itself, it was issued in Vienna with the support of the Philological Society in Bucharest, Romania. A chief impetus for its publication was philologist Adamantios Koraïs, of whose works the UC Classics Library possesses a premier collection. The last issue of the journal was published on May 1, 1821. Its last editor, Konstantinos Kokkinakis, was imprisoned in Austria, accused of collaborating with the revolutionaries. Burnam Classics Library GlassCase1 AP85.H385.

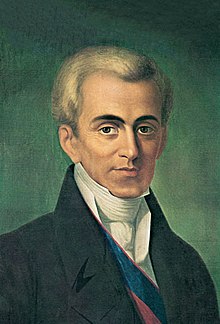

Adamantios Koraïs who was born in Smyrna (Izmir) in 1748 and died in Paris in 1833 was a leading proponent of a unifying language and a tireless advocate for the importance for Greeks to know and take pride in their own history whether they lived in the areas controlled by the Turks or in one of the many diaspora communities in Europe and elsewhere. The language he proposed, Καθαρεύουσα (Katharevousa), meaning purifying or purified, was to unite the contemporary Greeks with antiquity, but at the same time make the ancient and medieval texts approachable and understandable by all Greeks who spoke a people’s language, the vernacular, Δημοτική (Demotiki). It was also to be a purer Greek language devoid of the many “vulgarities,” loan words, from Turkish, Italian, and Latin, a compromise between Attic Greek of the fifth century BCE and the contemporary. This sense of renewed appreciation for the ancient Greek heritage before the Revolution has been labeled progonoplexia (ancestor obsession) and arkhaiolatreia (worship of antiquity). Nationalists even began to baptize their children using ancient Greek names rather than, as was customary, the names of Christian saints. Even though the Greek-Orthodox Church had been important for a sense of Greek unity and language, some also viewed the church leaders as too subservient to the Muslim Ottomans, which has been given as one of the reasons for military intervention.

Exhibition of the works of Ἀδαμάντιος Κοραῆς, Adamantios Koraïs, Burnam Classics Library.

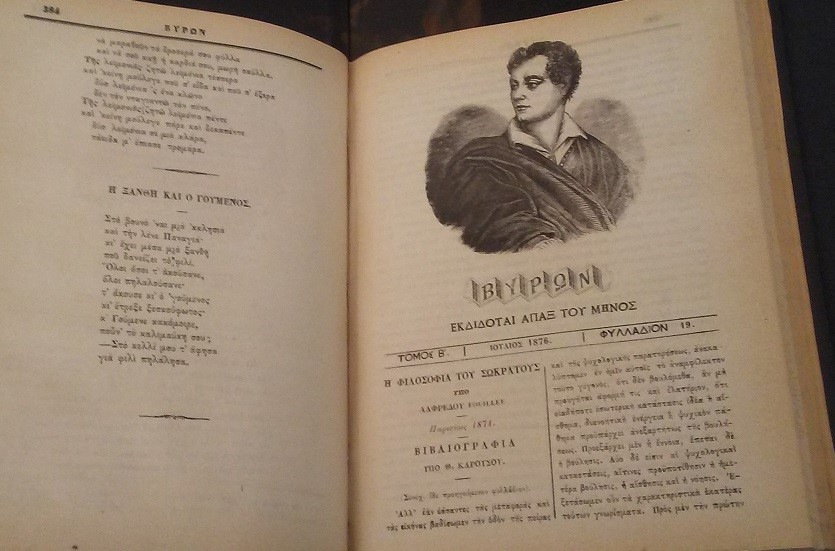

The most famous philhellene, Lord Byron

In his “Monroe Doctrine” speech of 1823, President James Monroe proclaimed that “an independent Greece is the object of our most ardent wishes” and the English poet Lord Byron, by that time already a superstar also in America, left for Greece to fight against the Turks. He was to give his life at Missolonghi on April 19, 1824. Cincinnatians did not learn of his passing until July 7. Because of the siege of Missolonghi, information was difficult to relay. There has been much speculation about the cause of death of Lord Byron. The most frequent cause given is rheumatic fever which he may have contracted on the voyage from Italy to Greece in 1824, or shortly upon his arrival in Missolonghi, or malaria which he may have contracted already during a visit to Patras in 1810. Consequences of neurosyphilis has also been given as a potential cause. Byron traveled with his personal physician, the Italian Francesco Bruno. German philhellenic doctors Julius Mellingen and Heinrich Treiber and Greek physician Loukas Vagias, the personal doctor of Ali Pasha, also treated Byron during his last few weeks with laxatives and blood-letting to no avail.

This is the last full poem Byron wrote, on January 22, 1824. He had arrived at Missolonghi three weeks earlier.

‘Tis time the heart should be unmoved,

Since others it hath ceased to move:

Yet, though I cannot be beloved,

Still let me love!

My days are in the yellow leaf;

The flowers and fruits of love are gone;

The worm, the canker, and the grief

Are mine alone!

The fire that on my bosom preys

Is lone as some volcanic isle;

No torch is kindled at its blaze–

A funeral pile.

The hope, the fear, the jealous care,

The exalted portion of the pain

And power of love, I cannot share,

But wear the chain.

But ’tis not thus–and ’tis not here–

Such thoughts should shake my soul nor now,

Where glory decks the hero’s bier,

Or binds his brow.

The sword, the banner, and the field,

Glory and Greece, around me see!

The Spartan, borne upon his shield,

Was not more free.

While reading about the details of the Revolution below, the following songs tell the story in Greek and may also act as nice background music.

Songs about the Greek Revolution and Independence (some of the videos have moving images of enactments from the War)

Underpinnings to and stages of the Greek War of Independence

“Greece 2021.” This website offers a useful timeline.

“Names from the Greek Revolution.” This webpage lists the names in alphabetical order of all the individuals mentioned below.

One of the many heroic incidents which preceded the Revolution occurred when women of Souli in Epirus committed suicide by jumping off a cliff to their deaths together with their children rather than being captured by an invading army under the Ottoman-Albanian leader Ali Pasha in 1803. It is thought that shepherds had escaped to the area to avoid Ottoman rule because of Souli’s isolated location in the mountains. The legend says that the women were singing and dancing before they jumped, an event which is referred to as the “Dance of Zalongo.” The Monument of Zalongo by George Zongolopoulos was erected in 1961 to commemorate this tragic story.

The emergence of Filikē Etaireia (“Society of Friends”), founded in 1814 in the Russian city of Odessa (today in Ukraine) and modelled on the masonic lodges and with links to the Italian Carbonari, marked a turning point in the development of the Greek nationalist movement. Its founders, Emmanouil Xanthos (1772–1852), Nikolaos Skoufas (1779–1818), and Athanasios Tsakalof (1788/1790–1851) were all merchants. A rumor circulated that the Society had the backing of the Russian state and was supported by the Tsar himself. The Filikē Etaireia and diaspora communities in cities such as Paris, Vienna and Odessa were the catalysts for the formation of the nationalist movement.

The founding triumvirate of the Filikē Etaireia.

On February 22, 1821 Alexandros Ypsilantis (1792–1828) an officer of Greek descent serving in the Russian army, crossed the River Prut into Moldavia with a legion of volunteers numbering about five hundred men. From there, he moved southward in the direction of Bucharest, which he reached on March 17, but could not hold for long. At the same time, an insurrection was underway in the Peloponnese. March 25, 1821 is officially identified as the start of this rebellion and this date is now celebrated both as the Feast of the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, and as Greek Independence Day.

Theotokos

After the rebels had gathered at various points in the Peloponnese and central Greece at an agreed time, they succeeded relatively quickly in bringing a large part of the region under their control by compelling the local Ottoman forces to retreat to a small number of fortresses, which were then besieged and surrendered. Only Tripoli in Arcadia, the civil and military center of Ottoman rule, managed to resist for a longer period and was only captured at the end of September in 1821 after a bloody battle, which was followed by a brutal massacre of the predominantly Muslim population. After the Peloponnese and central Greece were freed, the insurrection spread in the spring of 1821 to the Aegean islands, particularly Hydra, Spetses and Psara, which played decisive roles in the maritime war in subsequent years. The rebellion also flared up in other regions, such as in Thessaly, Epirus, southwest Macedonia, on the Chalkidiki Peninsula and in Thrace, though these were quickly suppressed.

As news of the uprising in the Peloponnese spread, there were attacks on the Greek population in various cities. Among the victims of these attacks was the patriarch of Constantinople, Gregor V (1745–1821). The most vicious attack was on the people of Chios, later known as the “Massacre of Chios” (Η σφαγή της Χίου), which together with the death of Lord Byron provoked international outrage and led to increasing support for the Greek cause worldwide. In April 1822, orders were given to kill all children under the age of 3, all men over the age of 12, and all women over the age of 40 and enslave the rest.

Eugène Delacroix (1824), The Massacre at Chios

Many of the Greek rebels viewed the conflict as a religious war between Christians and Muslims. The most conspicuous example of this was the decision to make the cross, the symbol of the rebellion, part of the flag of Greece and the Coat of Arms. Fittingly, there are conflicting opinions as to the meaning of the nine white and blue striped lines. Either they represent the nine syllables in the phrase Ελευθερία ἠ Θάνατος (Freedom or Death) or the nine Muses, the ancient Greek goddesses and protectors of various art forms.

The cross symbol was included in the Greek revolutionary Constitution of Epidaurus, which was adopted on January 1, 1822. It was the first document of its type which explicitly claimed jurisdiction over the entire Greek nation and it also contained the first official instance of the rebels referring to themselves as Hellenes. The Constitution of Epidaurus marks an important step in the political transformation of the revolt into a national rebellion.

The core territory of the War of Independence consisted of three main historical regions: the Peloponnese or Morea, the central Greek mainland including Attica and the island of Euboea, which was generally referred to as “Roumeli,” and the Aegean islands.

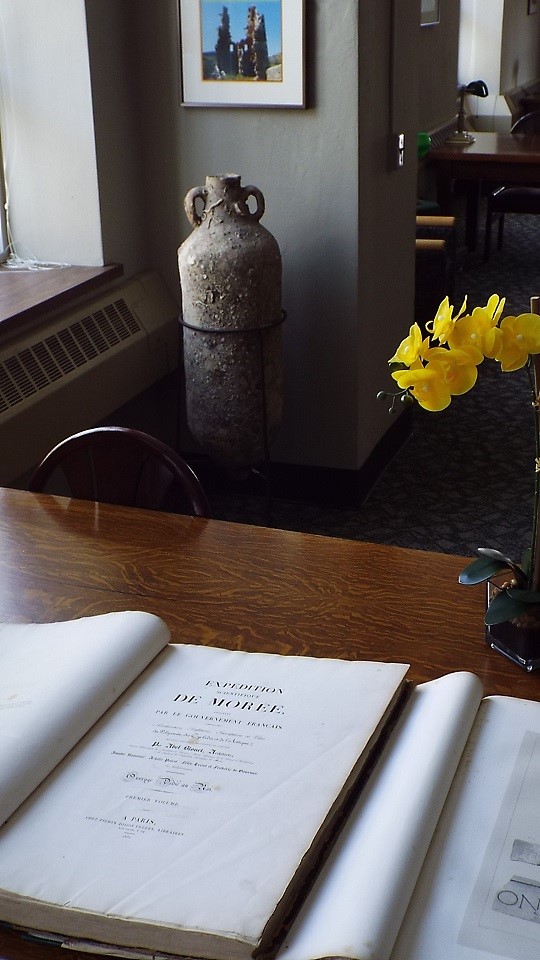

Expédition scientifique de Morée, ordonnée par le gouvernement français. Architecture, sculptures, inscriptions et vues du Péloponèse, des Cyclades et de l’Attique mesurées dessinées, recueillies et publiées par Abel Blouet … Amable Ravoisié, Achille Poirot, Félix Trézel et Frédéric de Gournay. Paris, Firmin Didot, 1831-38. Burnam Classics Library Eleph cl-g DF77 .E9. L’Expédition de Morée was the name of the land intervention of the French Army into the Peloponnese (Morea) between 1828-1833 to expel the Ottoman-Egyptian occupation. It was accompanied by a scientific expedition carried out by the French Academy.

Two of the military leaders instrumental in the War were Ioannis Makrygiannis (1797–1864), the son of a trader from central Greece, and Theodoros Kolokotronis (1770–1843), a brigand leader from the Peloponnese who in 1822 gained an important victory over the Ottomans.

Ioannis Makrygiannis (1797–1864)

The intervention of the great powers was not limited to the field of international diplomacy. In October 1827, a united British, French and Russian naval squadron sank an Egyptian fleet in the Bay of Navarino (ancient Pylos, where UC has been leading excavations under archaeologists Carl Blegen and Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker in the 20th and 21st centuries). The sinking of the Ottoman-Egyptian fleet at Navarino was an important event for the establishment of an independent Greece, a process which was further cemented in the subsequent year when Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire, forcing the Ottoman government to accept the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829, which included a provision for Greek autonomy.

After Civil Wars and the Ottomans regaining control over various areas including the Peloponnese, on April 4, 1826 Great Britain and Russia signed a protocol in St. Petersburg which envisaged the creation of an autonomous Greek state under Ottoman suzerainty as the solution to the conflict. However, the Protocol of St. Petersburg, which was followed by a similar agreement between Great Britain and France in the following year (the London Convention of July 6, 1827) represented the beginning of these states’ active participation, and also started a process which ended in 1830 and 1832 with the creation of the sovereign kingdom of Greece.

1821 Before and After (1821 Πριν και Μετά). This is a nice tour of the Benaki Museum in Athens telling the story of the Revolution in art. It is guided by historians Tassos Sakellaropoulos and Maria Dimitriadou, curators of the exhibition.

A series of 21 historical documentaries about the Greek Revolution by Georgios P. Malouchos and presented by Tassos Nousias will air on Greek TV on Thursday, March 25th 2021. See the trailer.

Yet, Freedom! yet, thy banner, torn, but flying,

streams like the thunderstorm against the wind.

Those who will not reason, are bigots, those who cannot,

are fools, and those who dare not, are slaves.

Why I came here, I know not;

where I shall go it is useless to inquire

– in the midst of myriads of the living and the dead worlds,

stars, systems, infinity, why should I be anxious about an atom?

Tyranny is far the worst of treasons.

Dost thou deem none rebels except subjects

The prince who neglects or violates his trust is more a brigand than the robber-chief.

— Lord Byron (1788-1824)

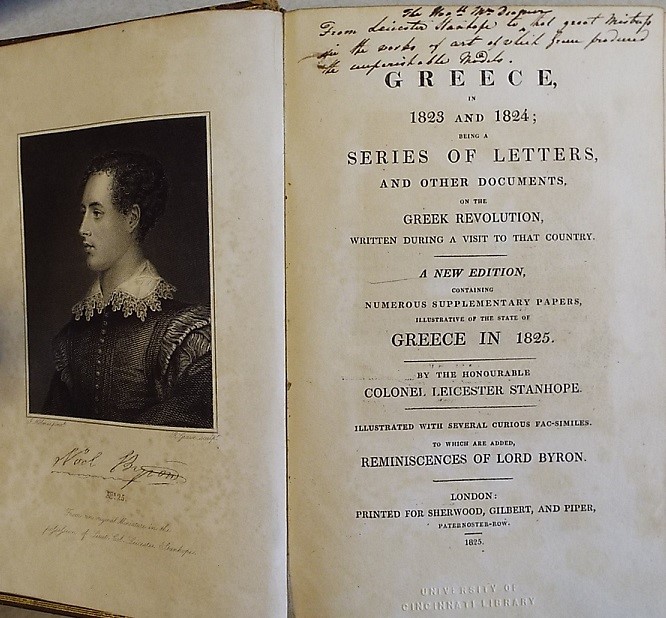

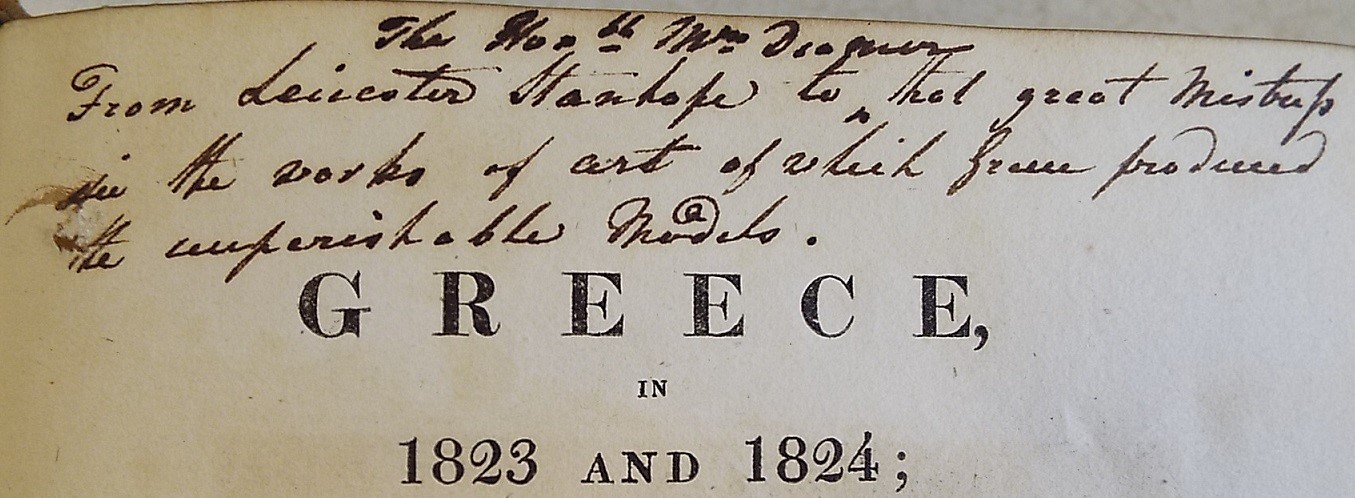

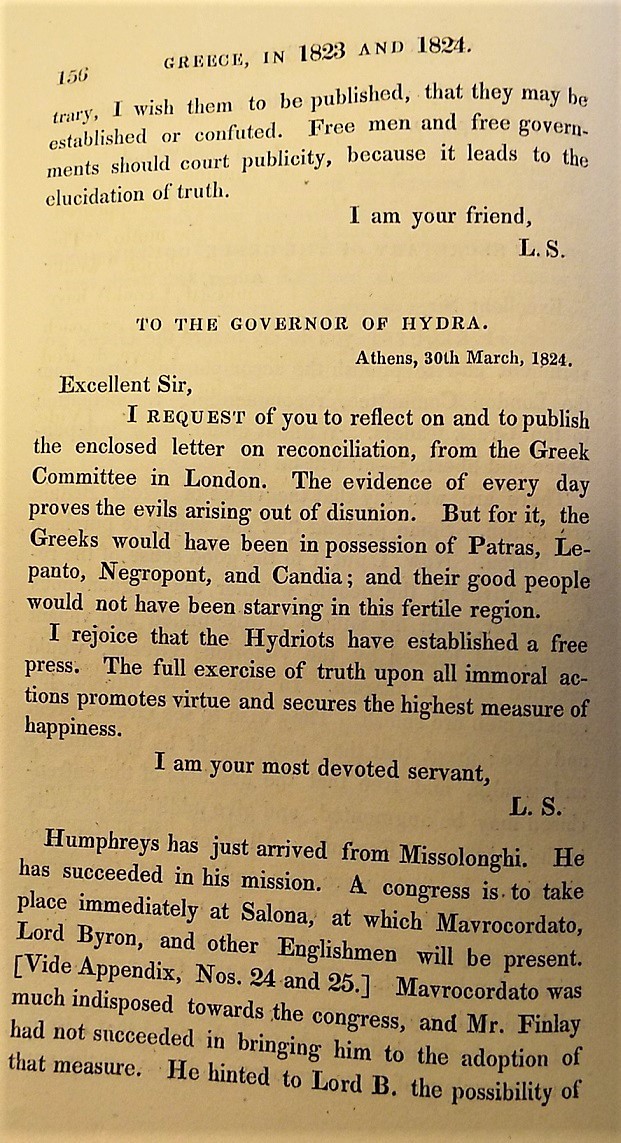

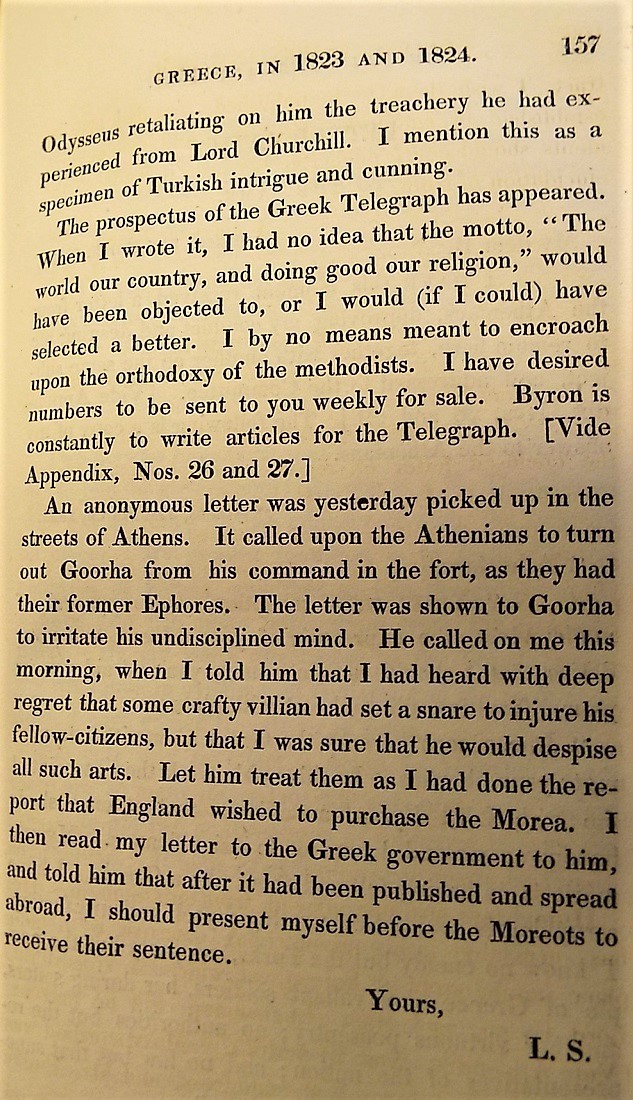

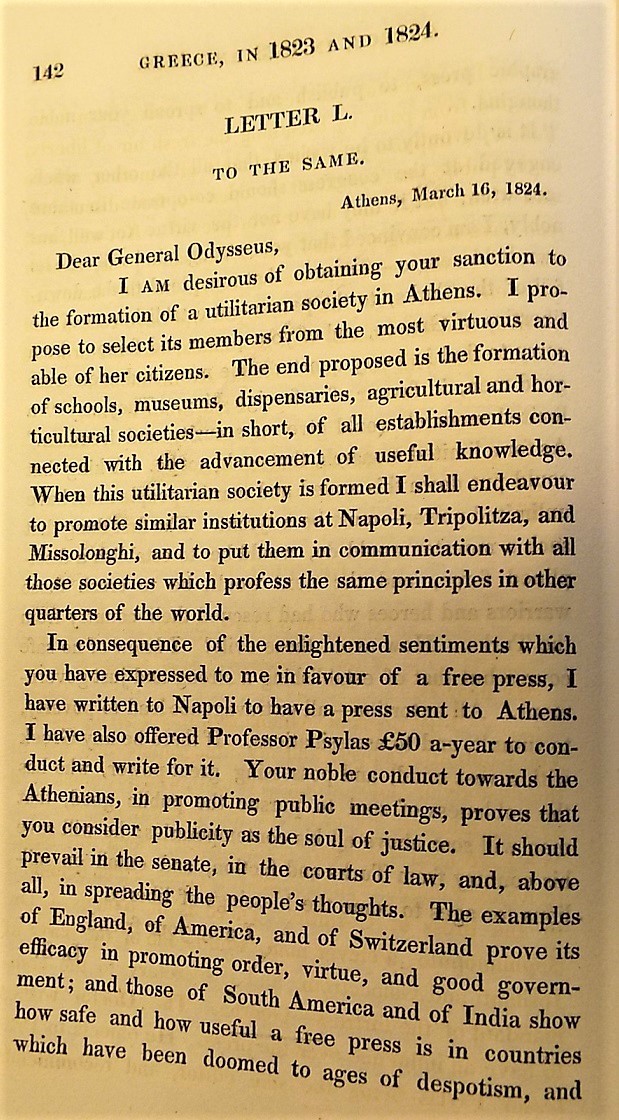

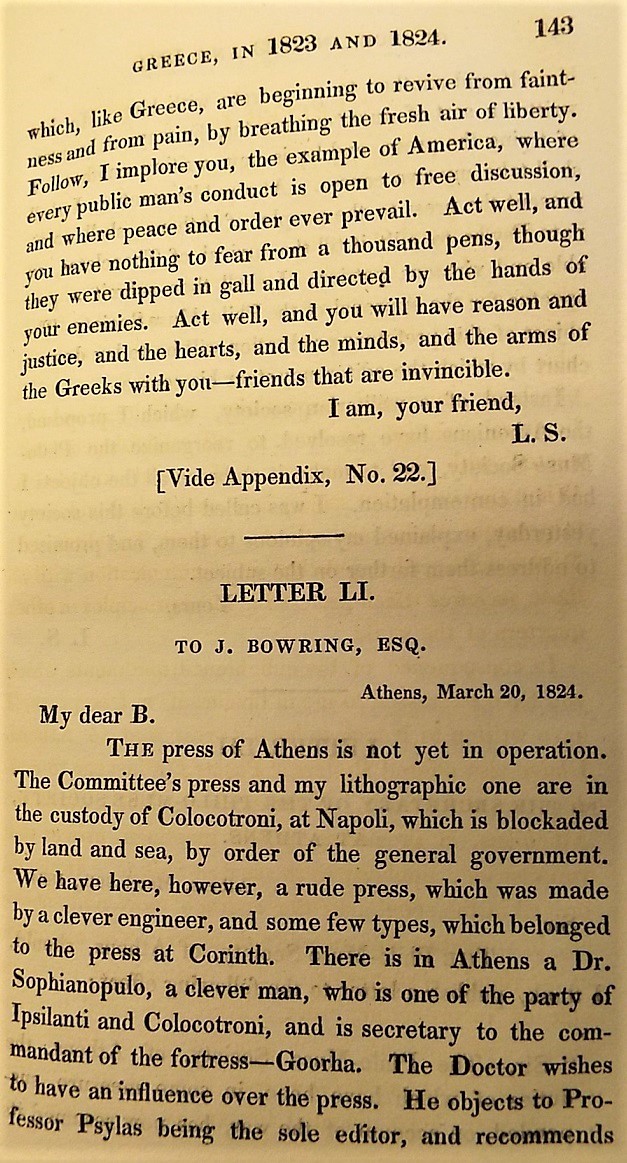

Stanhope Harrington, Leicester Fitzgerald Charles. Greece, in 1823 and 1824; a series of letters, and other documents, on the Greek revolution, written during a visit to Greece. A new edition containing numerous supplementary papers, illustrative of the state of Greece in 1825. The library’s gold leafed copy, the first American edition, is signed and dedicated by Stanhope. Burnam Classics Library DF806.H32 1825a

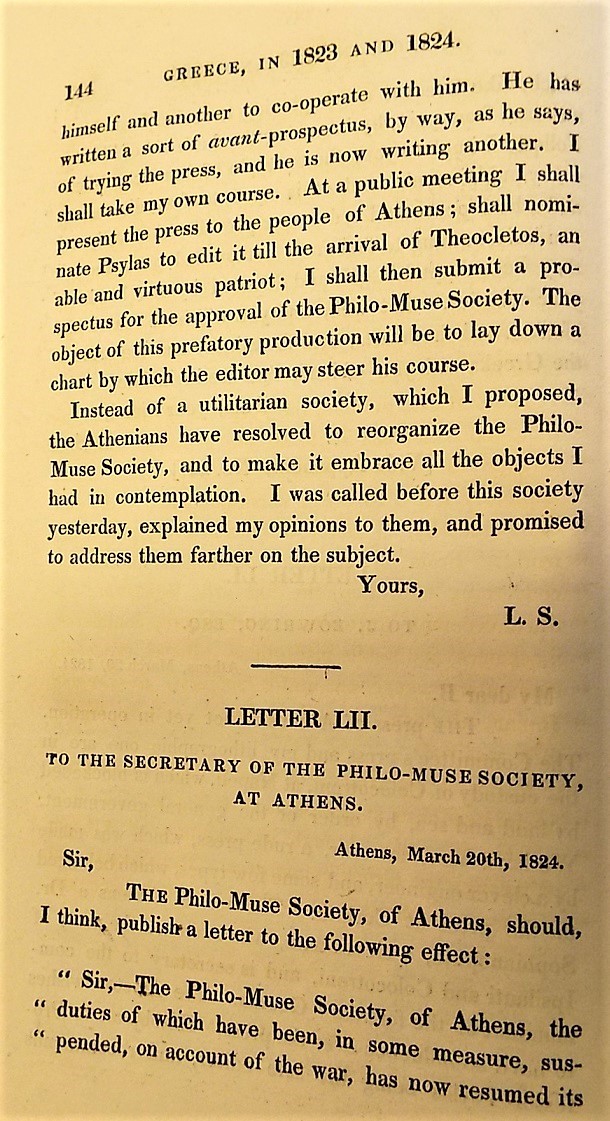

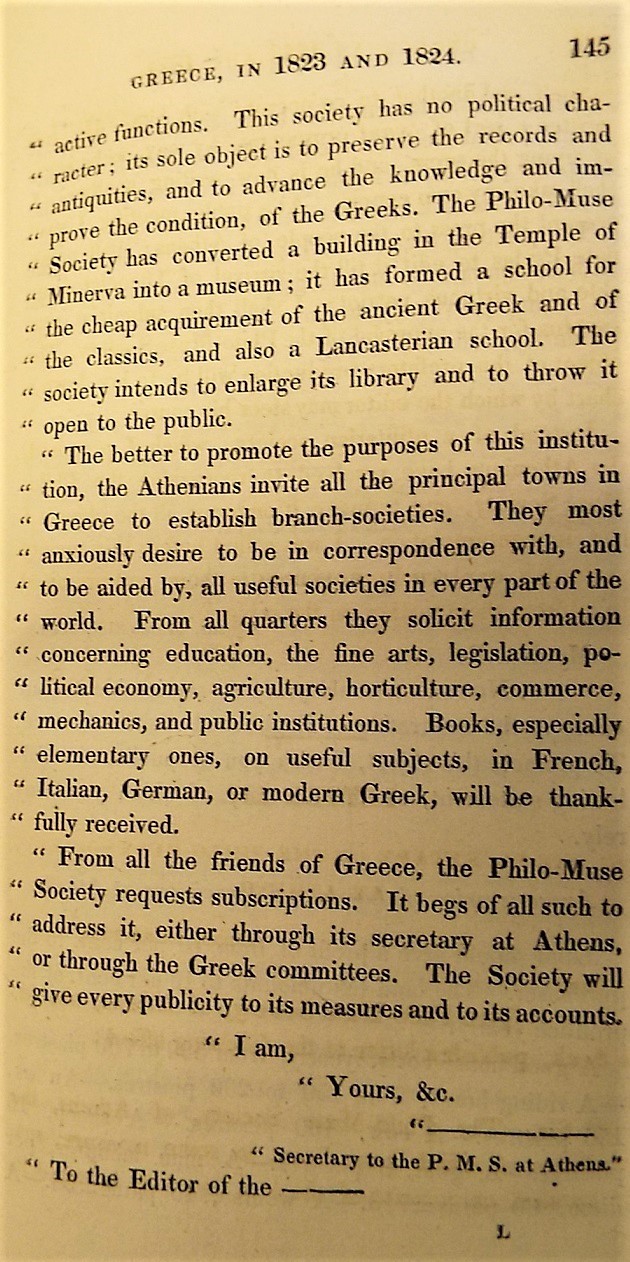

On February 28, 1823, the Philhellenic Committee of London was founded by Leicester Stanhope, Edward Blaquiere, Lord Byron, Jeremy Bentham, and John Bowring. A member of the London Greek committee, philhellene Colonel Stanhope’s priority when arriving in Missolonghi was to establish a newspaper, “The Greek Chronicle”. Within a few days he had set up the press with the Swiss chemist Meyer as editor. The first issues were published in January of 1824. Soon Stanhope launched a second paper, “The Greek Telegraph.” A third followed thereafter, “The Athens Free Press” or “Ephemerides of Athens.” “The Friend of the Law” was set up on Hydra. They promoted a free press and the importance of education. However, they seem to have been read mostly by philhellenes rather than by the general Greek population. Stanhope wrote several letters to various individuals and authorities (published in the book above). He not only used his money to set up presses, but also to organize military troops to fight the Ottomans. He further established a postal service and schools based on the Lancastrian model, named after Joseph Lancaster, whereby teachers taught older children, who in turn taught younger children. A few Greek boys were sent to England. English philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham helped with some of the expenses. They were to be educated and return to Greece as school masters. Together with the Greek military leader Odysseas Androutsos, Stanhope envisioned founding not only schools, but also museums, dispensaries, agricultural and horticultural societies. In March of 1824, the Philomuse (Friend of Music) Society of Athens was formed. Its aim was “to preserve the antiquities, to advance knowledge and to improve the conditions of the Greeks.” Stanhope’s Greek career came to an end in May of 1824 with a letter from the British authorities ordering him to return to London.

A third revolutionary constitution was passed in May of 1827, modelled on the American constitution of 1787 and the concept of presidential democracy. The principle of a democratic balance of powers, which was a feature of the earlier constitutions, was deserted in favor of a strengthening of the power of the executive branch with the unanimous election of Ioannis Kapodistrias (1776–1831) as the first ruler (Κυβερνήτης) of Greece with a seven-year term of office.

Ioannis Kapodistrias (1776–1831)

After arriving in the then capital city Nafplio in early 1828, Kapodistrias initiated a program of development. It addressed the administrative organization of the state territory, which was divided into departments in line with the policy of centralization that Kapodistrias pursued. It also included the homogenization of the judicial process and the creation of a professional military. Kapodistrias further created the first foundations of a public educational system and the beginnings of a social welfare program, and introduced significant measures in the areas of economic and fiscal policy. These comprised innovations in the agricultural sector, including the introduction of modern equipment, the introduction of new crops such as the potato, as well as the establishment of an agricultural school in Tiryns. Additionally, maritime trade was stimulated by means of legislative measures and targeted measures to combat piracy. As early as February 1828, a state commercial bank was founded to mobilize domestic and foreign capital reserves and a national currency, the not long-lived Phoenix, was introduced.

In September of 1831, Kapodistrias was assassinated by members of the Mavromichalis family. This family had incited a revolt on the Mani Peninsula, which they controlled, and Kapodistrias had suppressed the revolt with Russian assistance and had had the head of the family, Petrobey Mavromichalis (1765–1849), arrested. It was rumored that British and French consular representatives ordered the attack. It was in the interests of Great Britain and France to restrict Russian influence in Greece, and they viewed Kapodistrias as an obstacle to that.

After the death of Kapodistrias, a triumvirate consisting of Theodoros Kolokotronis (1770-1843), Ioannis Kolettis (1774-1847), and Augoustinos Kapodistrias (1778–1857), the younger brother of the assassinated ruler, assumed power. In December of 1831, they convened yet another National Assembly in Argos, which quickly appointed Augoustinos Kapodistrias as president. More internal strife ensued. The creation of the Greek state was ultimately the result of various international treaties of Great Britain, France, Russia and the Ottoman Empire. The borders of the state were finally established by the Treaty of Constantinople of July 9, 1832 as well as by the London Protocol of August 18, 1832, which proclaimed Prince Otto of Bavaria as the first king of Greece.

Ephēmeris tēs kyvernēseōs. Athens 1833. The establishment of a monarchy. Burnam Classics Library cl-g J7 .G92 1833.

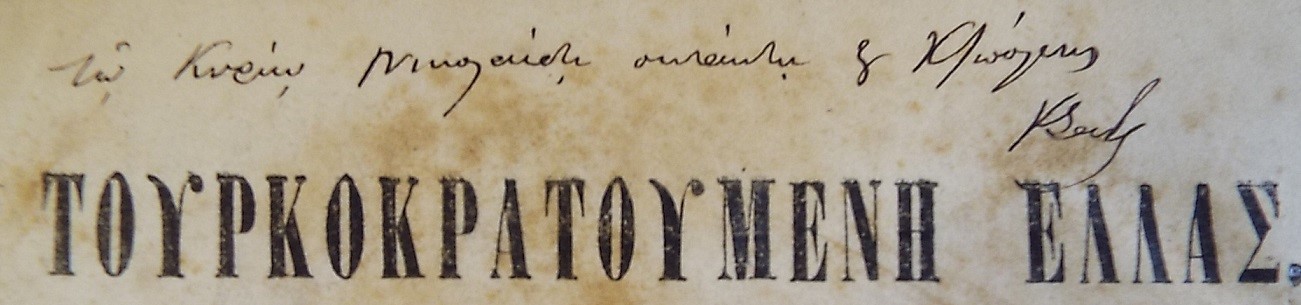

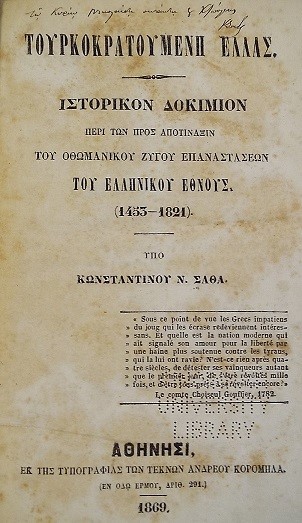

Κωνσταντίνος Σάθας (Kōnstantinos N. Sathas) Τουρκοκρατούμενη Ελλάς: Ιστορικόν Δοκίμιον Περί των προς Αποτίναξιν του Οθωμανικού Ζυγού Επαναστάσεων του Ελληνικού Έθνους, 1453-1821 (Turkish-Occupied Greece: A Historical Essay on the Greek Nation’s Uprisings to Overthrow of the Ottoman Yoke), 1869. Burnam Classics Library DF803.S25

The beauty of elderly Greek women.

Contributions of Women to the Greek Revolution

There were many women in the forefront of the Greek Revolution and philhellenism in Europe and America, also Greek women living outside of Greece such as Manto Maurogenous (1796-1840) who was initiated into the Filikē Etaireia in 1820, equipped the Greek forces and participated in operations while sending letters to Europe in attempts to influence public opinion, and Laskarina Bouboulina (1771-1825), born on Hydra, who was initiated into the Filikē Etaireia in 1819. She procured ammunition and ships to the revolutionaries. The histories of both women are tragic. Even though they were heroes who fought alongside men and even commanded naval ships, Bouboulina was murdered by a family member of a girl from Spetses whom her youngest son wished to marry (Bouboulina had seven children from two marriages). The family member opposed the marriage because Bouboulina was at the time poor after having donated her vast fortune to the War. Posthumously, the Russians gave her the, for a woman unique, title of Admiral. Maurogenous, who was born in the diaspora community of Trieste and who had also fought alongside men and who had successfully warded off an invading Turkish army on Mykonos, died destitute after donating her vast fortune to the war efforts and after scurrilous rumors had been circulated about her, which eventually led to her being deprived of a house which the new Greek government had given her in the early capital city of Nauplio.

Laskarina Bouboulina (1771-1825)

Among influential female philhellenes were Roxandra Stourtza (1786-1844), famed French author Madame de Staël (1766-1817), and Elisabeth Santi Loumaki-Chenier (1729-1808) whose salon was a meeting point for Paris’ intellectuals in the early 19th century and spurred “Hôtel Hellénophone,” the first secret pre-revolutionary organization for the liberation of Greece. “Hôtel Hellénophone” aimed to recruit new members and send weapons to Greece to prepare for the revolution. Princess Sophia Albertina of Sweden (1753–1829) founded a women’s philhellenic committee, turning the palace into a center of philhellenism with hundreds of women giving money to the Greek freedom struggle. Anna Eynard-Lullin (1793-1868), a Swiss painter and philanthrope, founded a philhellenic women’s committee in Geneva and organized performances, receptions and concerts to raise money. Polish Emilia Sczaniecka (1804-1896) founded the “Committee for Aid to the Greeks” and organized fundraisers for the orphans of the fighters, as well as for the care of the wounded. Mary Shelley was a close friend of Lord Byron and wrote a philhellenic science fiction novel, The Last Man, which describes a dystopian future in which the Greeks are trying to retake Constantinople, when an epidemic originating in the city devastates the future world. A number of female poets wrote philhellenic poetry — English Agnes Strickland (1796-1874), French Amable Tastu (1798–1885), Germans Amalia von Imhoff-Helvig (1776-1831) and Louise Brachmann (1777-1822).

For more information, see “The Contribution of Greek and Philhellene Women to Greek Independence“.

See also, Οι γυναίκες της ελληνικής επανάστασης του 1821. Σύζυγοι, μάνες, κόρες, αδελφές… ηρωίδες!

and this Wikipedia entry for a list of Greek female revolutionaries in alphabetical order, Κατηγορία:Αγωνίστριες του 1821

News media and artistic expressions

During the war, especially after the Massacre at Chios and the death of Lord Byron, donation appeals were organized in many western European cities and associations and committees were formed for the support of the Greeks. There was also much media coverage by the European press and after 1824 also by the American press. Newspapers, journals, newsletters, bulletins played a central role. Additionally, the media portrayals of the war included opinion pieces and memoir-style reports by philhellenes who were personally involved.

Statue of Lord Byron in the Garden of Heroes at Missolonghi

There were also literary works, and in particular poems, dealing with the War of Independence; for example, Victor Hugo’s (1802–1885) book of poetry entitled Les Orientales published in 1829 and Adelbert von Chamisso’s (1781–1838) cycle of poems entitled Chios (first printed in 1831) which was inspired by the massacre. Moreover, there were a number of theater plays written, for example, the drama Die Mainotten written by Harro Harring (1798–1870) in 1824, which depicted the rebel fighters on the Peloponnesian peninsula of Mani, and Gioachino Rossini’s (1792–1868) opera Le siège de Corinthe from 1826.

In addition, there were many visual depictions of the War, which covered a broad spectrum from popular engravings to oil paintings, for example, the famous paintings The Massacre at Chios (1824) and Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826) by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863). There were even fashionable clothing accessories in the “Greek style” and playing cards with depictions of prominent Greek freedom fighters, and the aptly named game “Phoenix and Half-Moon” (Bell and Hammer).

Eugène Delacroix, Ruins of Missolonghi (1826)

The military leader Ioannis Makrygiannis (1797-1864), mentioned above, reflected the sentiments of many in his Memoirs, “we didn’t think of how many we were, or that we have no weapons, or that the Turks were holding the castles and the cities… but the desire for freedom fell upon all of us like rain and everybody, people and clergy, and local administrators, and military people and the educated ones and the merchants agreed on this purpose and we made the Revolution.”

What about the past 200 years?

Greece’s history after the Revolution has sometimes been a turbulent one. King Otto was deposed in the 23 October 1862 Revolution, the passionate “language question” (katharevousa vs. demotiki) continued throughout the 19th and part of the 20th centuries. When the New Testament was translated into Demotic in 1901, riots broke out in Athens and the government fell. Crete was still under Ottoman rule and Greeks in Crete continued to stage regular revolts, and in 1897, the Greek government under Theodoros Deligiannis again declared war on the Ottomans. In 1910, Cretan politician Eleftherios Venizelos became Greece’s Prime Minister. By 1913, Crete, Epirus, and Macedonia were annexed by Venizelos through the Balkan Wars. After Greece’s involvement in World War I came the Greek-Turkish War, which resulted in a massive exodus of Greeks from Asia Minor and Turks from the Greek territories. Following this, the monarchy was abolished via a referendum in 1924; however, in 1935 after a coup d’état, the monarchy was restored. Then followed World War II. In 1940, Mussolini’s fascist forces invaded Greece leading to the Greco-Italian War. Greece’s victory over Italian forces by repelling them into Albania gave the Allies their first land victory. Both Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaul were full of praise for the Greek soldiers. A less welcome praise for the Greek army came from Adolf Hitler in the ensuing Battle of Greece. In WWII more than 100,000 Greek civilians died of starvation, tens of thousands more died as a result of reprisals by the Nazis, and the vast majority of Greek Jews were murdered in the Nazi concentration camps. Almost 1 million Greeks were left homeless. In 1965, George Papandreou’s government ousted King Constantine II and on April 21, 1967 a military coup brought the “Regime of the Colonels” to Greece. Under the Junta, civil rights were suspended and state-sanctioned torture became commonplace. In 1974, Turkey invaded the Greek island of Cyprus, which led to the regime’s collapse and the restoration of democracy. Since 1974 things have been relatively calm with frequent government changes, alternating between the conservative New Democracy party and the socialist PASOK party, although in recent years the left-leaning party SYRIZA has overtaken PASOK as the second largest party, though, through democratic processes. At the time this is written, New Democracy and Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis are in power. The antagonism between Greeks and Turks has not abated although there was a period of something resembling friendship after the devastating 1999 earthquake in Turkey, but conflicts have again arisen because of Turkish challenges to Greek sovereignty rights in the Aegean Sea and its natural resources and violations of airspace.

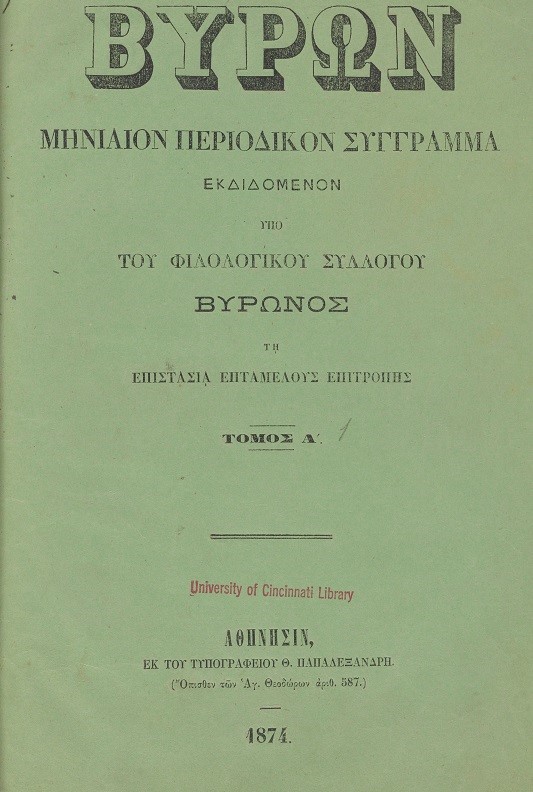

The Greek Digital Journal Archive (GDJA)

The Symposium of the Modern Greek Studies Association, Sacramento, November 2019

Zachary Quint, University of Michigan, and Rhea Karabelas Lesage, Harvard University, two of the members of the GDJA Steering Committee.

George Paganelis, Curator, Tsakopoulos Hellenic Collection, Cal State Sacramento, another member of the GDJA Steering Committee.

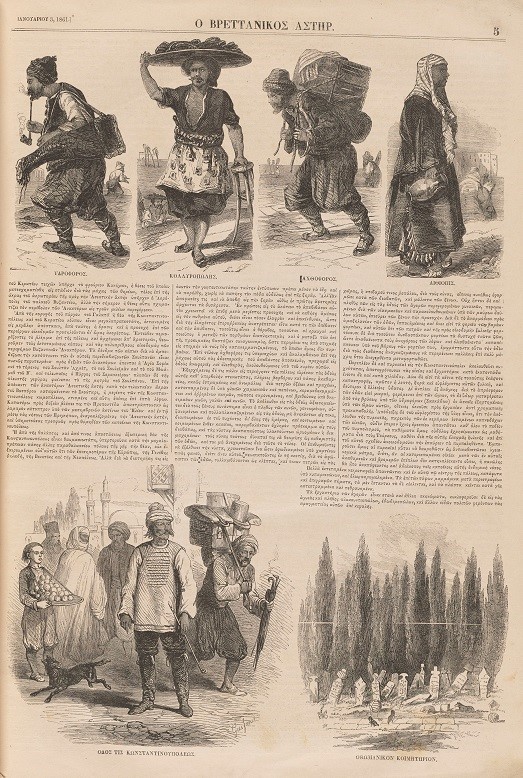

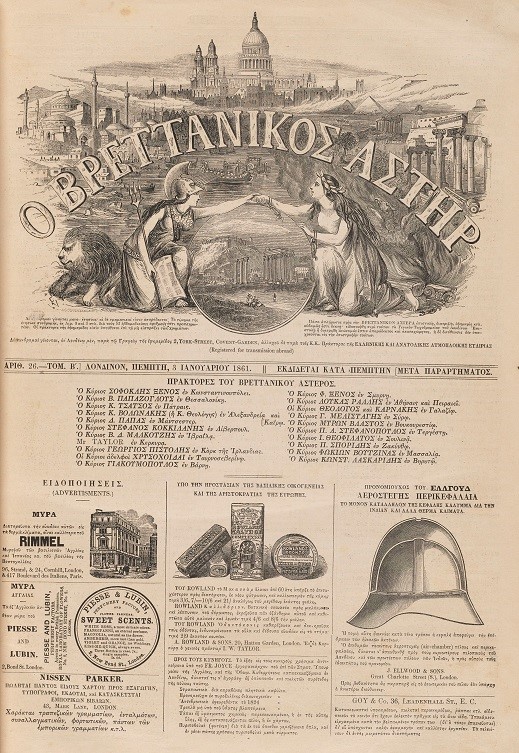

Ho Vrettanikos astēr. Hevdomadiaion periodikon. Idioktētēs kai archisyntaktēs Stephanos Xenos. Londinon, 1860-63. One of the many rare historic journals in the Burnam Classics Library cl-g AN85.A7 B8.

Scanned articles from books and journals from the time of the Greek Revolution

- Hermēs ho Logios April 7 1821

- Hellēnika Chronika April 19 1824, Lord Byron’s death

- Stanhope 1825 pp. 530-551

- Stanhope 1825 pp. 322-325

- Hellēnika Chronika August 6, 18, 1824 Lord Cochrane

- Hellēnika Chronika color 1824 Washington December 7

- Hellēnika Chronika 7 December 1824 cont.

- Hellēnika Chronika September 2, 1824 Nafplio, American ship

A few Modern Greek book treasures in the John Miller Burnam Classics Library

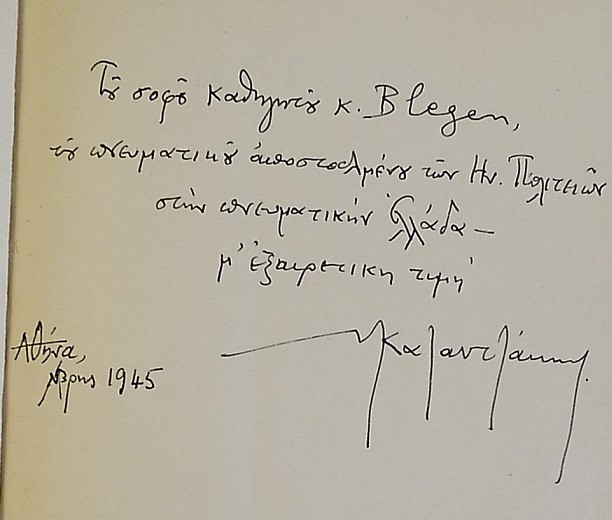

Nikos Kazantzakis. Anglia; Athens, 1945. Burnam Classics Library DA DA630 .K3 1945. A note from the famed author and addressed to Cincinnati archaeologist Carl Blegen.

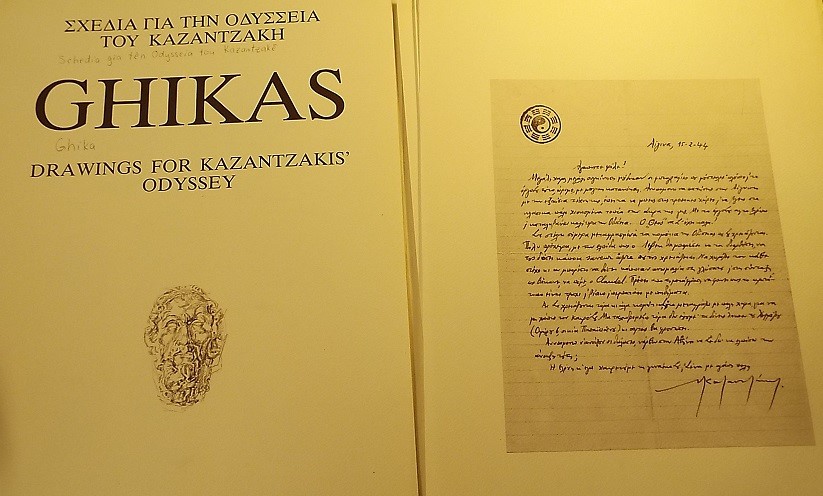

Greek Cubist artist Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas’ (1906–1994) illustrations to the famous Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis’ (1883–1957). The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, including 34 color plates and a facsimile of a letter from Kazantzakis to Ghika from 1944.

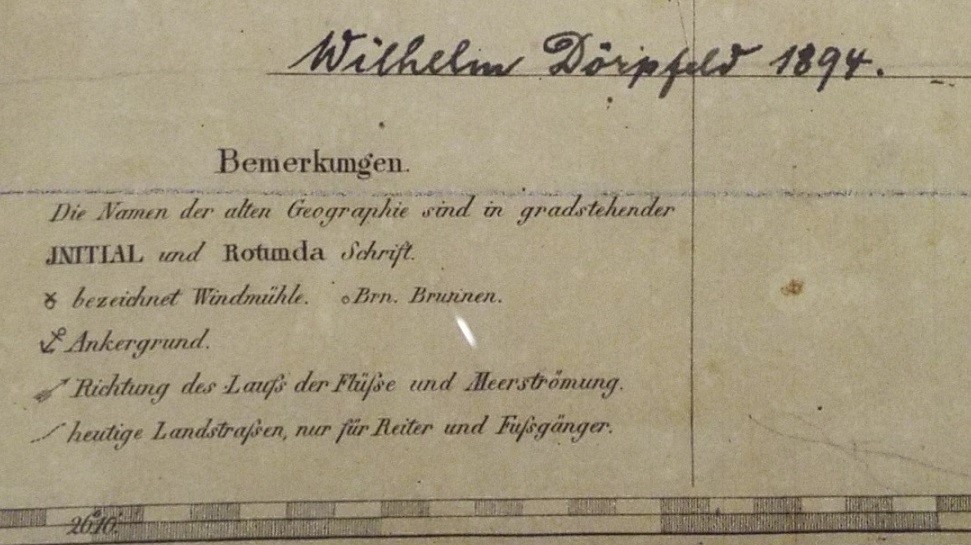

Dörpfeld, Wilhelm (signature on map). Spratt, Thomas Abel Brimage (author). Die Ebene [cartographic material] von Troia Aufgenommen und Entworfen von T. Spratt … hrsg. mit den am ort bestimmten Namen der alten Geographie versehen und mit einer topographischen und physiographischen Erklärung begleitet von Dr. P.W. Forchhammer. 1850. Burnam Classics Library DF221.T8S82. In the late 1800s, German archaeologist Dörpfeld was the Assistant Director of the original excavation of Troy under Heinrich Schliemann. Later he took over as Director. Excavations resumed in the 20th century (1932-38) under the directorship of UC professor Carl Blegen.

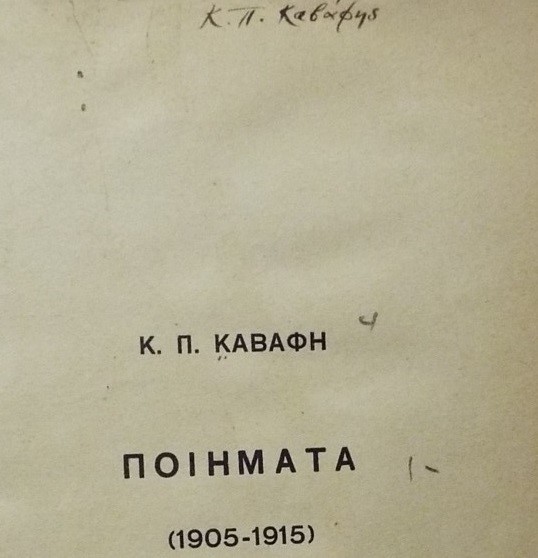

Constantine Peter Cavafy (Konstantinos Petrou Kavafis, 1863–1933) considered one of the greatest Greek poets of the 20th century was born in Alexandria where several of his poetry collections were self-published. The Library’s copy bears the author’s signature in his own hand. Burnam Classics Library, Glass Case I cl-g PA5610.K2 A17 1930.

An interesting recent poll shows that the majority of Greeks view the Filikē Etaireia as having played the most central role for Greek independence; philhellenism is also considered important, but somewhat less so. This poll with also other questions is from the website of a present-day Society for Hellenism and Philhellenism.

Greeks and Philhellenes — Let’s celebrate with wine, food, dance and music!

Καλή όρεξη!

Today’s young Greeks fight another battle, to protect our planet from climate change.

Today’s philhellenes flock to the free nation of Greece for its natural beauty.

- “The Visual Representation of the 1821 Greek War of Independence through the Eyes of Greek and Foreign Artists.”

- “The Street Artist Commemorating the Heroes of the War of 1821 is only 18-years-old.”

Χρόνια πολλά, Ελλάδα!

Bibliography

- Athanassopoulou, Effie F. “An ‘Ancient’ Landscape: European Ideals, Archaeology, and Nation Building in Early Modern Greece.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 20:2 (October 2002): 273-300.

- Catafygiotou-Topping, Eva (1973). “Cincinnati Philhellenism in 1824.”Cincinnati Historical Society Bulletin 31: 2 (1973): 127-141.

- Catafygiotou-Topping, Eva. “General William Henry Harrison, Philhellene.” Pilgrimage 2: 3: 8-11. This is a themed issue “American philhellenes and the Greek Revolution of 1821.”

- Allan Cunningham. “The Philhellenes, Canning and Greek Independence.” Middle Eastern Studies 14.2 (May 1978): 151-181.

- Earle, Edward Mead. “American Interest in the Greek Cause, 1821-1827.” American Historical Review. 33: 1 (October 1927): 44-63.

- Fatouros, Mitch, ed. Theodoros Kolokotrones Memoirs & the History of the Klephts prior to 1821, 2013.

- Geōrgiou, Nikolaos. Epistolē: pros tous ekdotas tou Logiou Hermou, 1817. Letter signed: Nikolaos Geōrgiou, and dated: 5 Septemvriou, 1817.

- Janssen, Marjolijne. “The Greek pre-revolutionary discourse as reflected in the periodical Ερμής ο Λόγιος (1811-1821)”(PDF). Cultural nationalism in the Balkans during the nineteenth century.

- Kitromilides, Paschalis M., ed. Adamantios Korais and the European enlightenment. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2010.

- Koraēs, Adamantios. Adamantiou Koraē Dialogos deuteros peri tōn Hellēnikōn sympherontōn. Hydra Typogr., 1827.

- Koraēs, Adamantios. Salpisma polemistērion. Alexandria: Atromētou tou Marathōniou, 1801.

- Koraēs, Adamantios. Sēmeiōseis ēis tō prosōrinon politeuma tēs Hellados tou 1822 etous. Athēns, 1933. Dyo prōta dēmokratika politeumata tēs Neōteras Hellados ; 2.

- Koraēs, Adamantios. Ti sympherei eis tēn eleutherōmenēn apo Tourkous Hellada na praxē eis tas parousas peristaseis, dia na mē doulōthē eischristianous tourkizontas: Dialogos dyo Graikōn deuteros. Ed. G. Pantazidēn. Paris: K. Everartou, 1831.

- Kyriakides, Stilpon P. The Northern Ethnological Boundaries of Hellenism. Thessaloniki: Etaireia Makedonikōn Spoudōn, 1955.

- Lascaris, P.-A. (Polymnia A.). Autoviographia Adamantiou Koraē. Paris, 1833.

- Lazos, Chrēstos D. (1983). Hē Amerikē kai ho rolos tēs stēn epanastasē tou 1821. Athens: Papazëzë Aebe. See especially “Ο Φιλελληνισμóς του Σινσινάτι,” vol. I, pp. 469-481.

- Mackridge, Peter (2009). Language and National Identity in Greece, 1766-1976. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Makriyannis, Ioannes. Memoirs. Vassilis P. Koukis (ed. and transl.). Athens: Narok, 2001.

- Santelli, Maureen Connors. The Greek Fire: American-Ottoman Relations and Democratic Fervor in the Age of Revolutions. Ithaka, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020.

- Travlos, Konstantinos, ed. Salvation and Catastrophe: The Greek-Turkish War, 1919-1922. Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2020.

- Zelepos, Ioannis. Greek War of Independence (1821-1832). EGO: European History Online. http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/european-media/european-media-events/ioannis-zelepos-greek-war-of-independence-1821-1832

/GreekSpinachPieSpanakopita-TheSpruceEats-cc27326c734a4fa98c041b49bf7ea676.jpg)

-5e580fa45d9f1.jpg)