Finally, the John Miller Burnam Classics Library has been able to move into the 21st century thanks to its staff and East View, an information services company, which has digitized one of the Library’s rarest and most important collections of Greek, British, and U.S. military maps from World War I and II. East View specializes in hard-to-find foreign language materials such as maps, newspapers and ephemera. In addition to helping us digitize and preserve the Burnam collection of maps, many in poor physical condition, the company has provided a searchable database free-of-charge for the Classics Library and freely available to the UC community.

During the Covid lock-down for some, the Library’s small staff were busy facilitating, among many other things, the digitization, the gathering of materials and bibliographic information, weighing, packaging, and shipping the many hundred maps to the Minneapolis-based company resulting in the digitization of more than 600 maps (some maps were too brittle to send) and a searchable database, which can be accessed using the following URL’s.

- From on campus: https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/udb/4770

- From off campus with UC authentication: http://uc.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://dlib.eastview.com/browse/udb/4770

- The database default displays thumbnail images. You can choose to open a PDF file for an overview or Hi-Res for a detailed view with zoom and pan capability when you place the cursor on a thumbnail.

- The records can be viewed as a Thumbnail – four squares within a square icon to the right above the entry; as Detail View (image + metadata) — two squares and two lines icon; as List View (metadata only) — three lines icon displaying title, publisher, etc.

- You can Sort results by date or title.

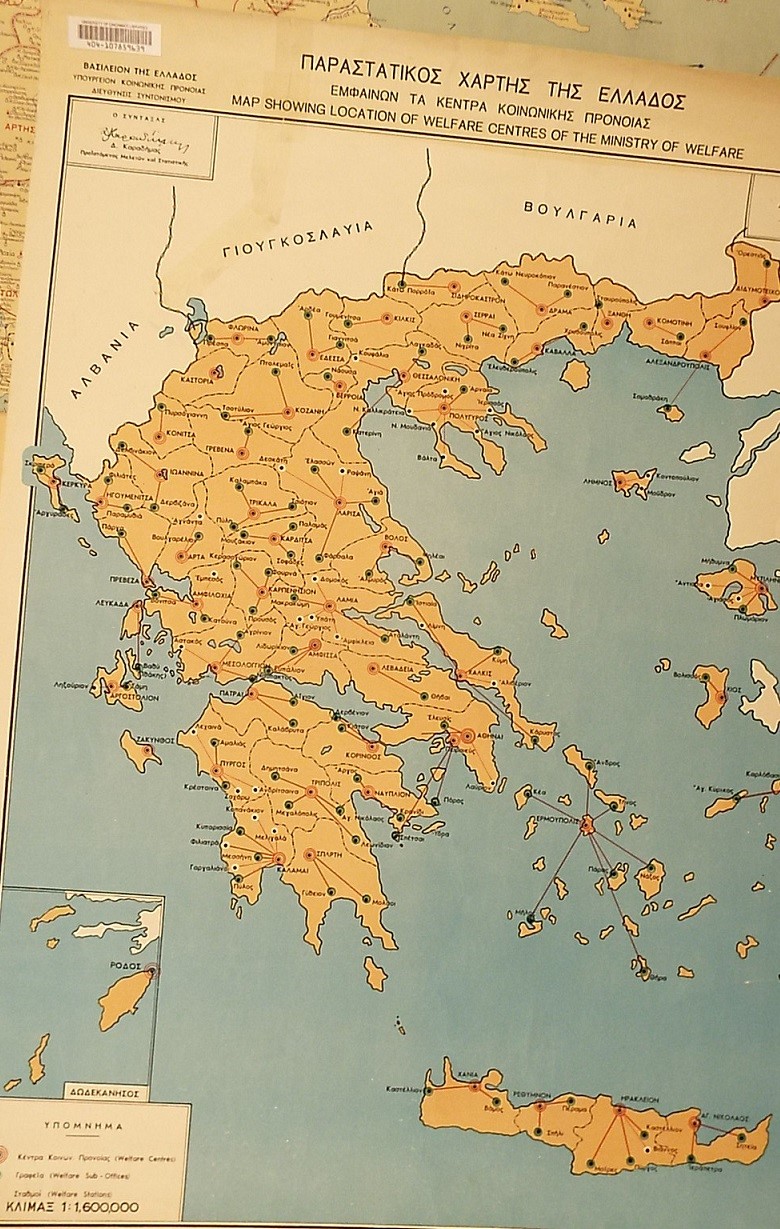

- The left panel allows you to select various filters, for example, collections, regions, publication type, subject (aeronautical, nautical, agriculture, city plans, economic geography, epoch of history, geology, historical geography, mineral resources, political administration, railways, religion, roads, topographic, tourist sites, transport, geography, etc.), publisher (CIA, U.S. State Department, OSS, Greek Ministry of Social Welfare, Apostolic Ministry of the Church of Greece, Ministry of Reconstruction, etc.), scale, country (Albania, Germany, Greece, North Macedonia, Turkey).

- You can either Browse the collection or type a Search term in the search box at the top left. Supposedly, search terms may be entered in any relevant language, including Greek; however, see my unsuccessful attempts below. Unlike in the Loeb and TLG, the virtual keyboard in the search box does not yet support Greek (it supports Ukrainian, Russian, Arabic, and other non-Roman alphabets), so you will need to change your computer’s settings to Greek under “Languages.”

- You can add Search terms with Boolean operators by clicking on the plus (+) sign to the right of the search box.

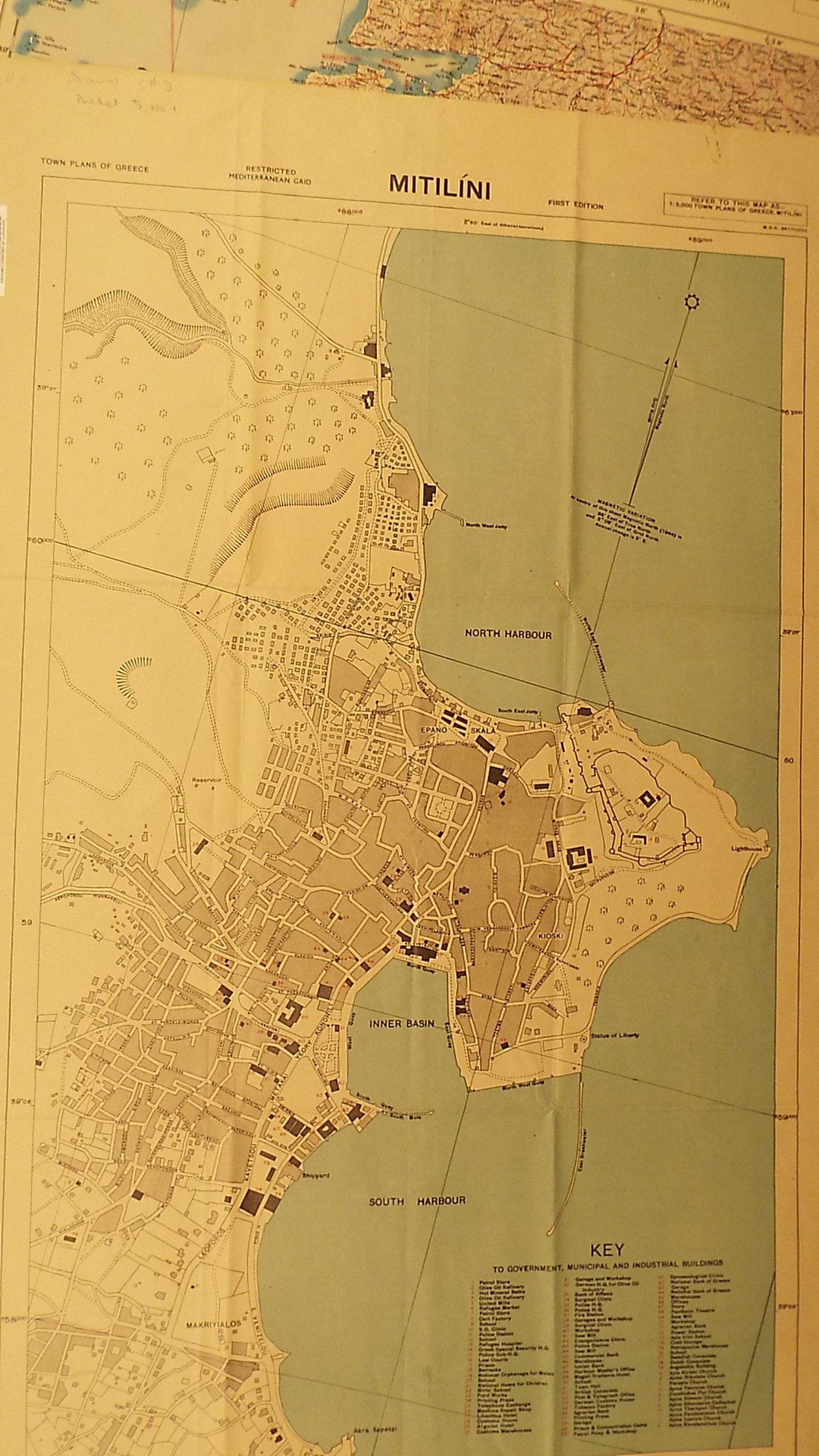

- There is no authority name search so Greek towns can be spelled in different ways depending upon the transliteration conventions in place at the time of the maps’ creation, so it can be Mytilene, Mitilini, Mityleni, etc., or if a Greek army map, Μυτιλήνη (ignoring diacritics).

- Even though the database is said to support Greek, this seems to be hit and miss. I tried Αίγινα (Aegina), Αλεξάνδρεια, Δελφοί without luck. Κρήτη yielded two results; Ἀθῆναι (not Αθήνα) the same. Ρόδος yielded results, but not Δήλος.

- The metadata and text information outside of the maps, NOT the maps themselves, have been OCR’ed, which may in part explain the above.

- You can view the Metadata of each map by clicking on the information symbol (i), above the selected map. It includes: title, barcode, drawer location in the Burnam Library, series, publisher, year, scale range, language, publication type, subject, country, persistent URL.

- A Citation tool is available if you click on the quotation mark (“) icon above an individual map, limited to the MLA, APA and Chicago styles, and RIS format.

- Note that when the date of an individual map says “1001,” it should rather say: [n.d.]. Hopefully, this will be changed since 1001 is an actual year.

- You can Download (down-pointing arrow icon above the map) and Print (printer icon) the maps except for those under copyright.

In spite of a few initial glitches and shortcomings, it is an incredibly valuable resource. The maps that have only been viewed by some since their acquisition, partly because they are not known to many, but also because of their location in a locked cabinet due to their brittle condition and significant monetary, historical, topographical, and political value, will now be much more accessible to the UC classics and Hellenic communities and our many visiting scholars, but also more easily examined thanks to the varied functionalities of the database.

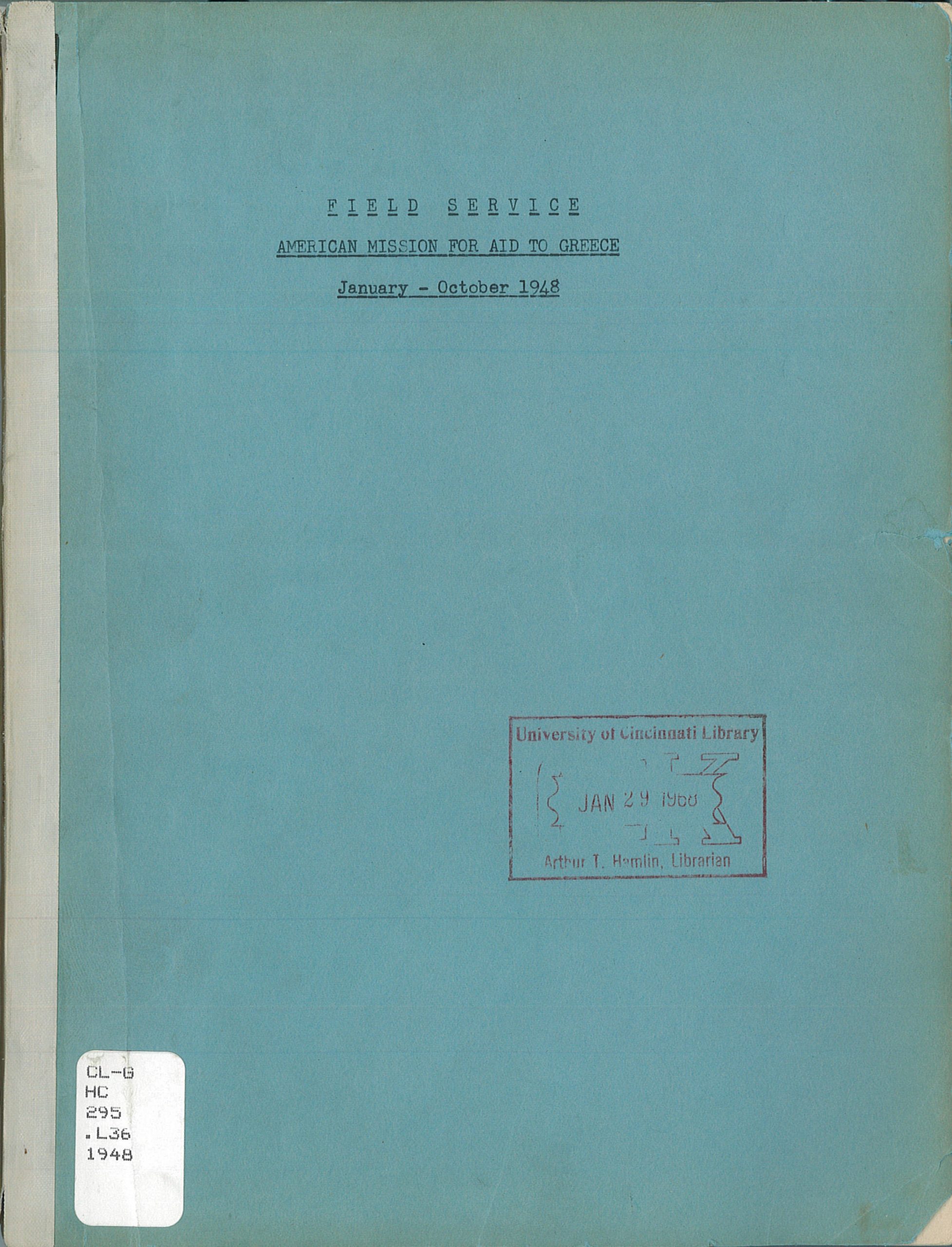

It is not entirely clear how all of these maps were acquired by the Classics Library. The 1972 map series was acquired in the 1990s at the request of Professor Jack Davis, so that we would have a good set of 1:50,000 maps. Other maps may have come to us thanks to Herbert P. Lansdale and Carl Blegen. Mr. Lansdale was born on March 7, 1898, in Baltimore, Maryland, and received his B.A. from Oberlin College. Just before the Second World War, he was appointed Director General of the YMCA of Greece. He returned after the war as a member of AMAG (the American Mission for Aid to Greece) and became the Director of its Field Operations Service. He died on September 13, 1988, in Palo Alto, CA, to which he had retired. His son Bruce McKay Lansdale served as Director of the American Farm School in Thessaloniki from 1954 to 1990.

The maps were invaluable to AMAG staff who studied the history of Greece, demography, economic and social issues, labor, public health, government and administrative organization in order to provide military aid, aid for agricultural and industrial rehabilitation and expansion, for housing construction and repair, etc.

Several of the maps document roads, railroads, agencies of the Greek Ministry of Social Welfare, sanitary situations, villages, centers of refugees from Macedonia 1940-45, centers for the U.S. Mission for Observation of Greek Elections, ecclesiastical maps, etc., all important to facilitate and document the work of AMAG following WWII. A professor at King’s College London who examined them in our collection said that many of these maps are unique to the UC Classics Library.

The maps were created with American funds from the early days of aerial photography mapping large areas of Greece. In 1944 the Nazis had destroyed master plates of most of the maps of Greece. The incredibly detailed maps in the John Miller Burnam Classics Library were produced from the subsequent aerial photographs. Initially, they concerned specific recovery projects, mining surveys of national electrification programs, land reclamation projects, mining surveys of inaccessible areas, and detailed terrain studies of sites for bridges, highways, and dams.

To learn about the work of AMAG, the ECA, the Marshall Plan, and the American Farm School in Greece:

- American Aid to Greece: 1945-1951. Economic Cooperation administration Mission to Greece (Marshall Plan), June 1951. CLASS Stacks HC295.A44 1951

- Final Report of AMAG. Field Service American Mission for Aid to Greece by Herbert P. Lansdale, January-October 1948. Athens: American Mission for Aid to Greece, 1948. CLASS Stacks HC295.L36 1948

- Master Farmer: Teaching Small Farmers Management. Bruce M. Lansdale. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1986. CLASS Stacks S562.5 .L35 1986.

- For a brief background on the Farm School in Thessaloniki, founded by Dr. John Henry House and his wife, Susan Adeline, in 1904, and still going strong as the American School of Agriculture, see https://www.afs.edu.gr/ιστορία/, and a more substantial account by Brenda L. Marder, Stewards of the Land: The American Farm School and Modern Greece. Boulder: East European Quarterly; New York: distributed by Columbia University Press, 1979. CLASS Stacks S539.G8 A455.

Moreover, the Classics Library possesses several weekly and monthly reports from AMAG and ECA.

President Truman’s address to Congress on March 12, 1947, in which he asked for aid to Greece and Turkey as part of the Truman Doctrine, was lauded in the Greek press. An editorial in Εθνικός Κήρυξ (National Herald) stated that “the battle against Soviet aggression started in Greece and will come to a head in Greece. We have proved worthy of U.S. aid” (Weekly Report of the ECA Mission to Greece and the American Mission for Aid to Greece, no. 11, March 18, 1949, p. 4).

The Marshall Plan for Greece is described as having its origin, more than a hundred years earlier, in the Greek War of Independence (last year’s bicentennial) when a Spartan soldier addressed an assembly in Kalamata with these words: “Having decided to live or die for freedom, we come to you for just sympathy, because it is in your country that liberty lives. It is in your country that liberty is loved by you in the way that our fathers loved it…”. Pan-Hellenic and Philhellenic societies had sprung up in New York and New England, also in Cincinnati, soliciting funds, food, clothing, and weapons. Many young American men decided to join the Greek army against the Turkish Ottoman rule. For more on this, see a previous blog from 2021 celebrating the bicentennial of the Greek Revolution https://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/liblog/2021/03/the-classics-library-commemorates-the-200-year-anniversary-of-greek-independence/ .

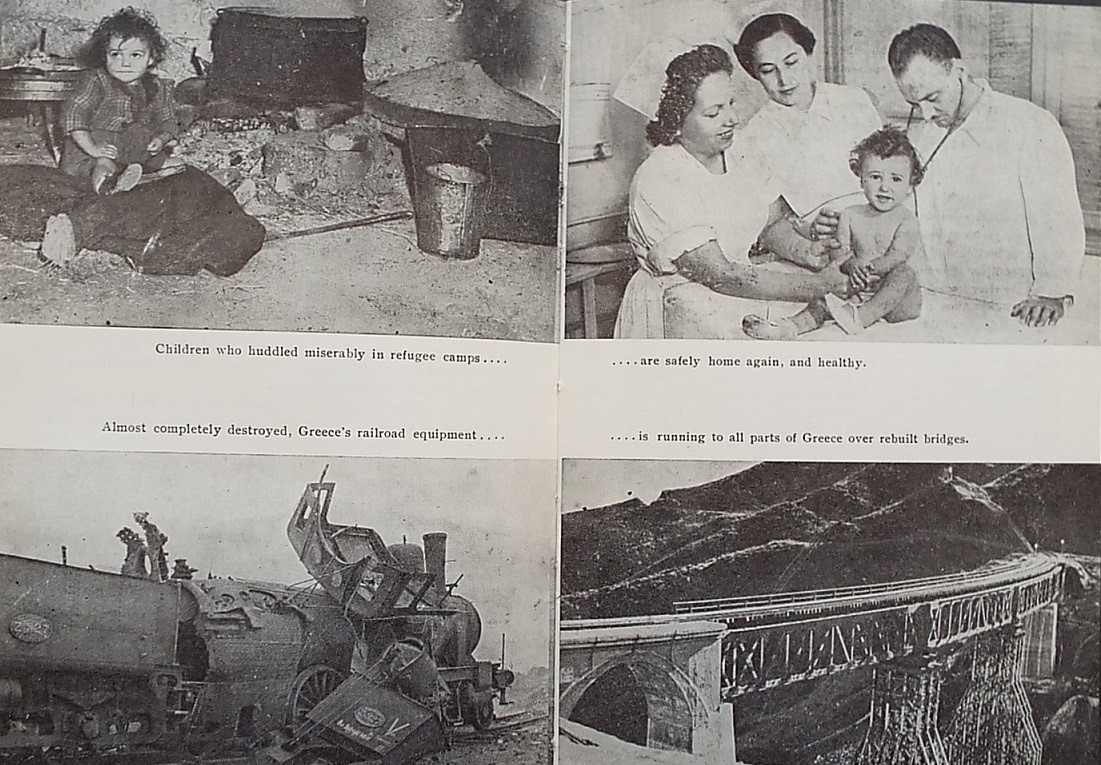

Fast forward more than a hundred years to the Marshall Plan which was brought about by the devastation of Greece by Fascists and Nazis in WWII, but also by Communist “guerilla warfare.” “In many ways, and particularly for the people of the rural areas, the misery and loss brought about in this communist insurrection was far worse than that inflicted by the Nazis and the Fascists” (The Story of the American Marshall Plan in Greece, July 1, 1948 to January 1, 1952. The U.S. Mutual Security Agency, Mission to Greece, p. 4). It was the beginning of the Truman Doctrine to contain communism which later led to the Marshall Plan. In March of 1947, President Truman went before Congress to request 400 million dollars of aid to Greece and Turkey. Congress granted the money and later added to it. The newly-formed American Mission for Aid to Greece (AMAG) came to Greece to administer the expenditure. The following year, in April 1948, Congress passed legislation establishing the Marshall Plan which provided economic aid to 17 European countries including Greece, and the AMAG phase came to an end. The Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) was a successor. In fact, U.S. assistance to Greece from 1944 to the end of 1951 amounted to more than 2 billion dollars. What did it achieve? “First, Greece has been saved to the west” (The Story of the American Marshall Plan in Greece, July 1, 1948 to January 1, 1952. The U.S. Mutual Security Agency, Mission to Greece, p. 7); “second, most of the damage inflicted by years of warfare [against the German Nazis, the Italian Fascists and the Communists] has been repaired”; “third, substantial progress was made…in the areas of agriculture and industry, in shipping and mining,” etc. The Marshall Plan was followed by the Mutual Security Program (MSP) on January 1, 1952, which focused more on boosting the military.

AMAG representatives were sent to many villages in Crete, the Dodecanese, Epirus, Thessaly, Thrace, Macedonia, Aetolia, Argolis and Corinth, Arcadia, Attika, Achaia, Euboea, etc., from July 1, 1947 to May 15, 1948. Local administrators could request that a representative visit a village to assess the need for and what kind of help to provide.

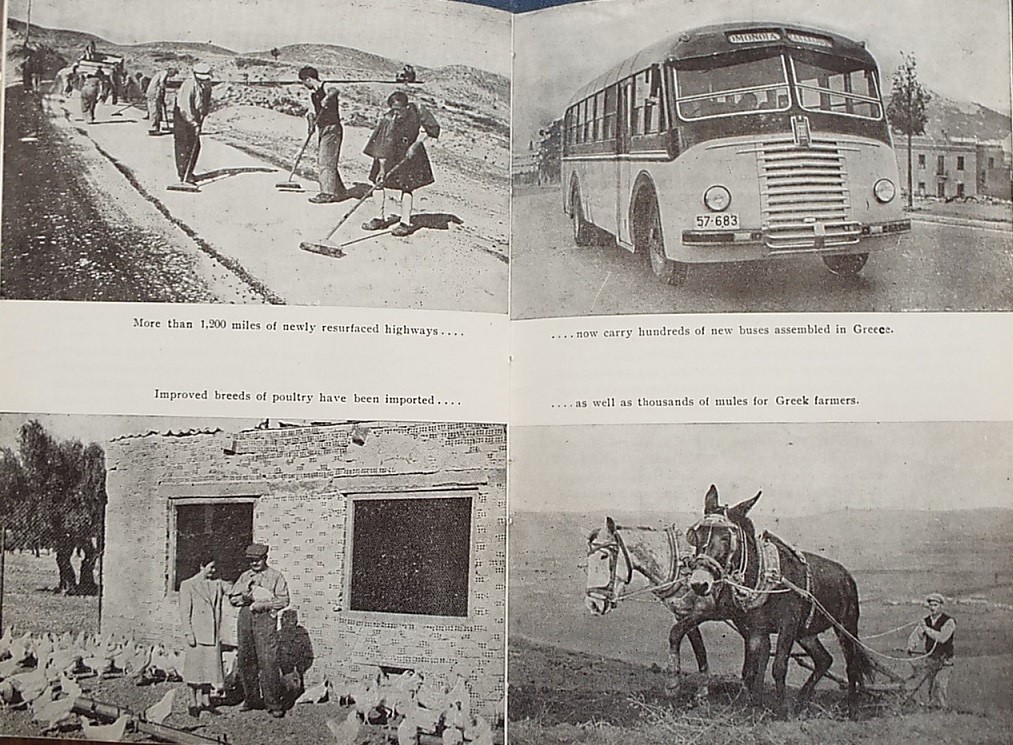

The U.S. government via AMAG provided money and engineering assistance for highways, ports, airfields, telecommunications, schools, bridges, housing, farm equipment; drilled wells and built dams, and focused on “live-stock improvement” such as providing artificial insemination stations and fishery concentration stations. AMAG worked out an agreement with the Turkish government to feed people in Thrace. In addition, AMAG distributed clothes, sole leather, meat paste, macaroni to both soldiers and civilians. It provided food for Macedonian and Thracian refugees – beans, macaroni, wheat, flour, milk — and medical supplies such as diphtheria, cholera, and smallpox vaccines, penicillin, ether, heart tonics, vitamins, bismuth (main ingredient in Pepto-Bismol), bandages, iodine. The long-range goal was “a self-sufficient economy and a revitalized Greek democracy.”

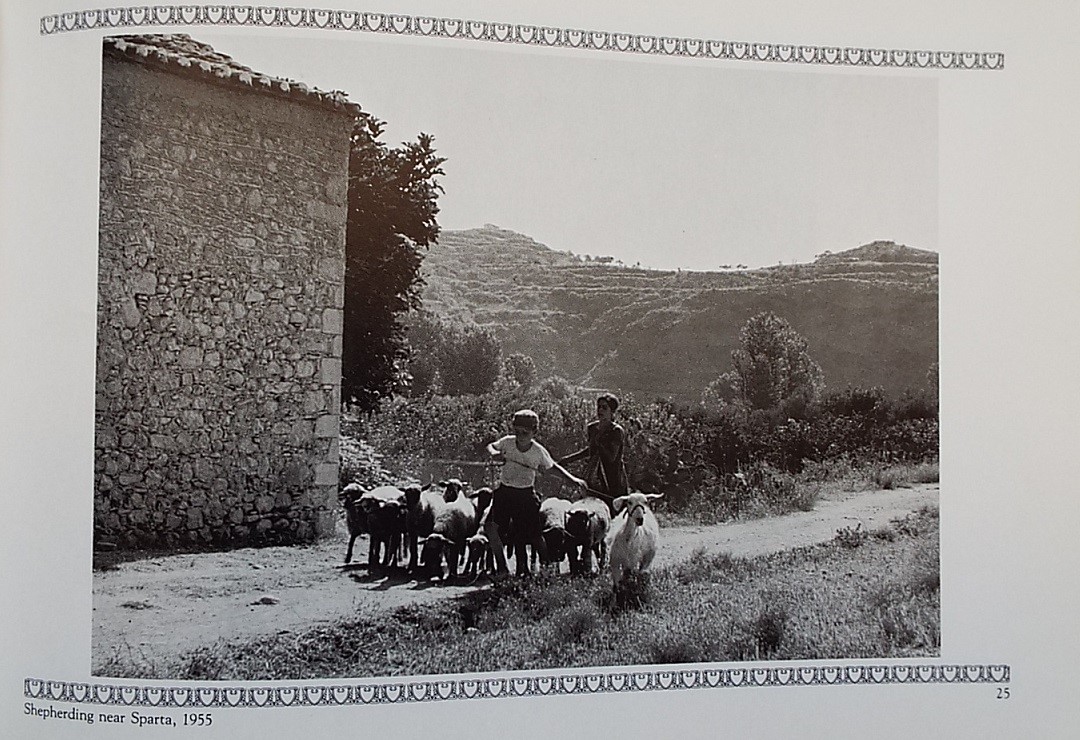

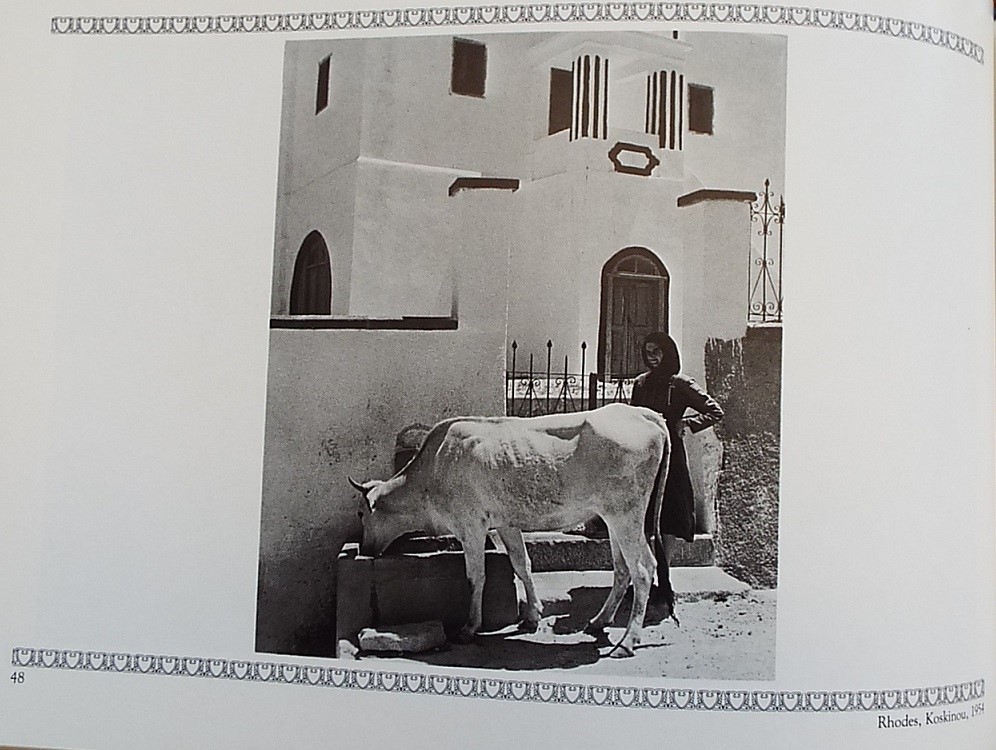

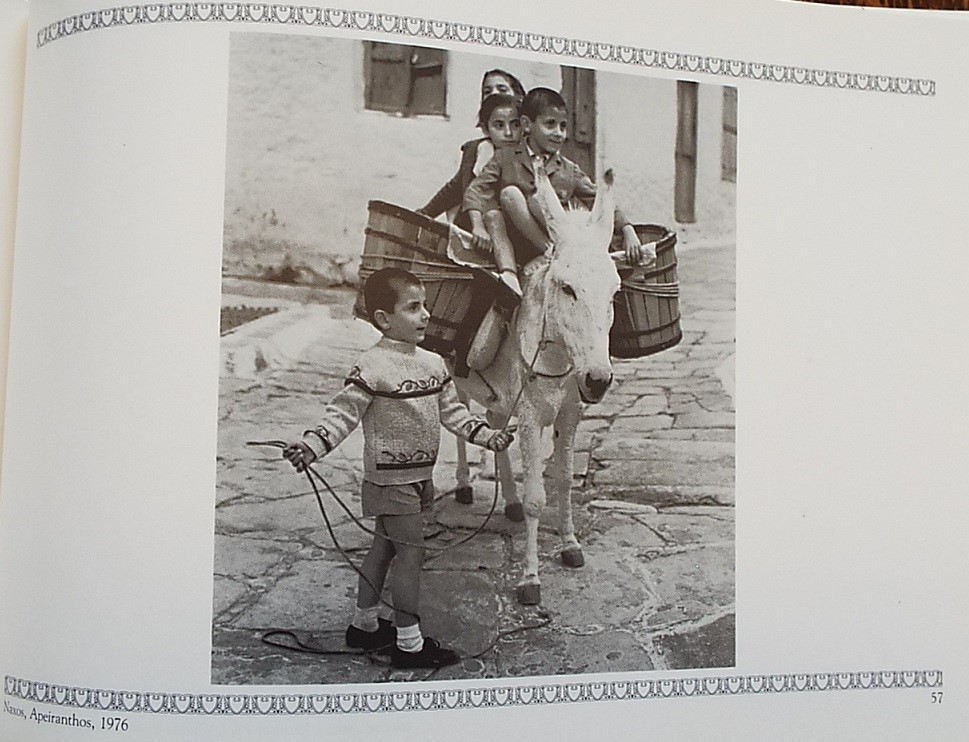

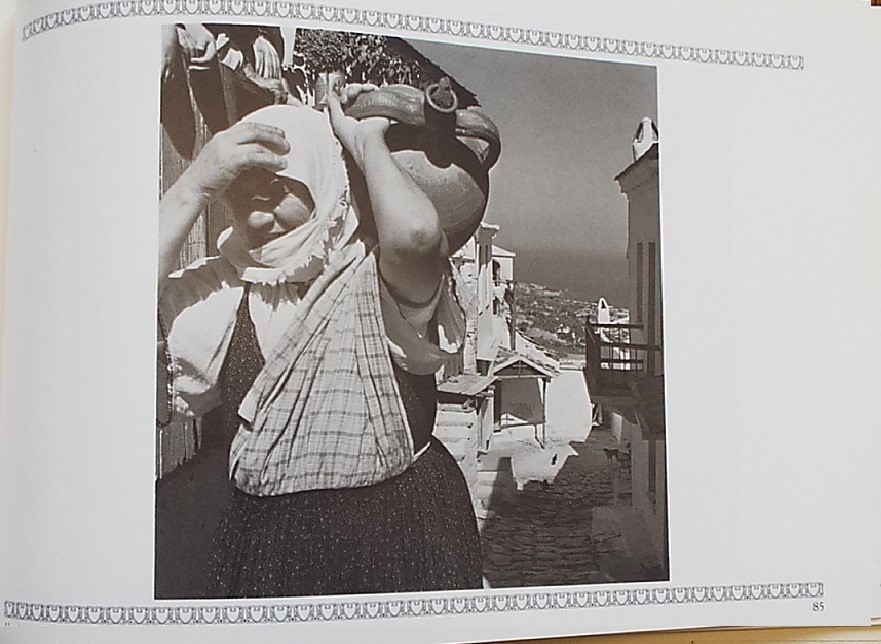

One of the many initiatives taken by the Americans was to strengthen the American Farm School founded already in 1904, to whose directorship Herbert Lansdale’s son Bruce was appointed. Professor Davis recounts that there are several connections between UC and the American School of Agriculture (Formerly Farm School). The father of a UC classics alumnus (Stelios Andreou) was chief veterinarian there in the 1950s. Another UC alumnus was president in the 1990s. The hostel housing students is named “Cincinnati House” and there has been a local Cincinnati support organization for the American Farm School. The mission of the Farm School was to provide vocational training for rural youths and adults to manage agricultural enterprises. In Bruce Lansdale’s account from 1948 he writes about the life of Greeks, before the war and American aid, that they “lived in simple, whitewashed, two-roomed stone or mud-brick houses with thatched or mud-tiled roofs. Families slept on straw mats on the earthen floor, which they covered with special mud. Many lived on the second floor and the lower floor housed animals and crops. Their diet was primarily bread, cheese, olives, and vegetables in season” [i.e., the Mediterranean diet], “with garlic to ward off disease. Milk was for sick people and babies. Meat was eaten only on feast days” [presumably for reasons of poverty, but it was also the practice in ancient Greece] “and chicken was considered a great luxury” (Master Farmer: Teaching Small Farmers Management. Bruce M. Lansdale. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1986, p. 17). Lansdale added that it [Greece] was “not Ethiopia, Tanzania, or one of the poorest countries in Central America, but a Greek village at the beginning of the twentieth century.”

AMAG representatives had made efforts to convince school teachers of the importance of giving school children (evaporated or dry skim) milk. In fact, it says that “an American aid worker should spend all his time convincing people to drink milk” (Final Report of AMAG. Field Service American Mission for Aid to Greece by Herbert P. Lansdale, January-October 1948. Athens: American Mission for Aid to Greece, 1948, Minutes, May 24, 1948, p. 3). Today we know that meat and dairy products can negatively affect human health, and meat and dairy production have also proven to have serious environmental consequences, being major methane and CO2 polluters. And garlic does indeed have many medicinal benefits, not the least of which is that it is a natural antibiotic, so maybe the “simple Greek villagers” who lived primarily on plant-based subsistence farming more in line with environmental sustainability had something to teach Americans as well?

Lansdale’s account describes unsuccessful attempts to introduce beef cattle into Greece (Master Farmer: Teaching Small Farmers Management. Bruce M. Lansdale. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1986, p. 102). President Dwight Eisenhower presented an Angus bull and two heifers to the school to be exhibited at the Thessaloniki Trade Fair, where they were viewed by thousands of people. Four years of trials with the Angus proved that no market existed for high-priced marbled beef and that the pasture land for this kind of cattle was insufficient in Greece. Another attempt also ended in failure when the calves were killed by wolves, disease struck the herd, and pastures dried up.

Another good intention, which we later learned had serious health and environmental consequences, described in the AMAG Report, was to spray (also by air) DDT to kill mosquitos which could carry malaria. The Report argued that refugees were good at housekeeping and white-washing walls and spraying the walls with DDT. The Report also states that dehydrated potatoes were given to refugees as Greeks did not want them. A report sent to AMAG asserted that “in Corfu the refugees are happy, well-sheltered, well-fed” (Final Report of AMAG. Field Service American Mission for Aid to Greece by Herbert P. Lansdale, January-October 1948. Athens: American Mission for Aid to Greece, 1948, Notes from Conferences, February 24, 25, and 26, 1948, p. 12) and that there are enough tents to house 100,000 refugees (Final Report of AMAG. Field Service American Mission for Aid to Greece by Herbert P. Lansdale, January-October 1948. Athens: American Mission for Aid to Greece, 1948, Notes from Conferences, February 24, 25, and 26, 1948, p. 16), though these seem to have been underused.

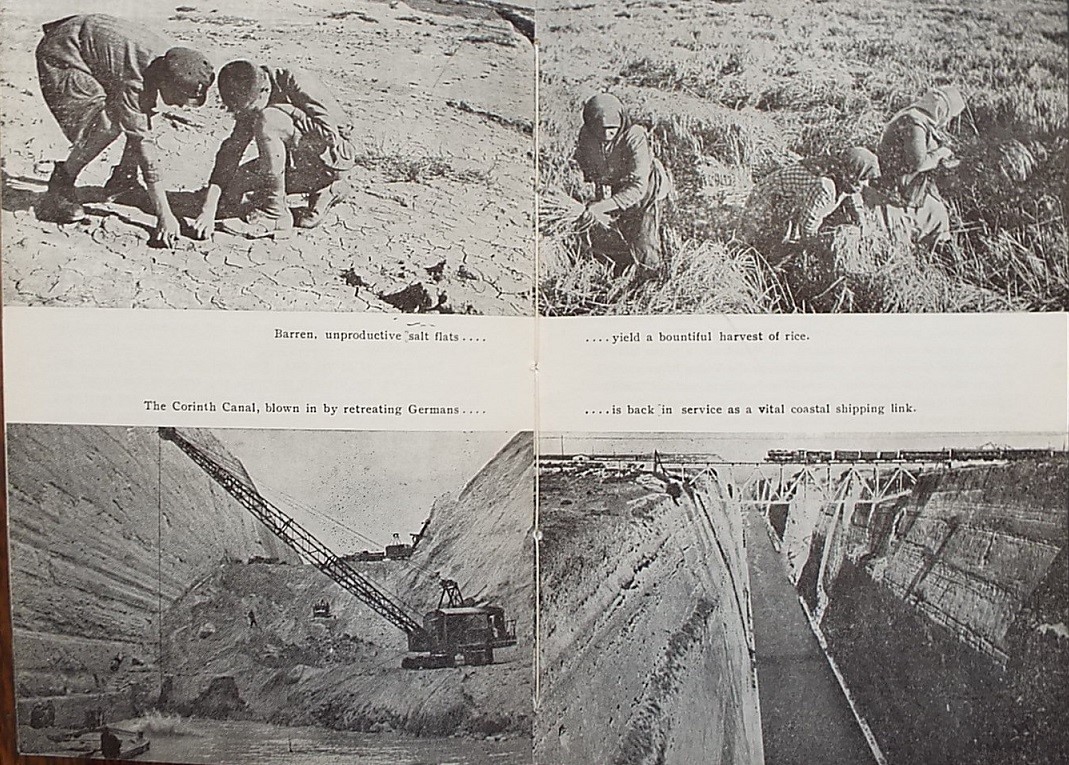

The Report concludes that Greece was an underdeveloped industrial nation with no fuel and no basic raw materials. Thus, there was a need for restoration to prewar levels (1938), but the aim was also to raise the level of industrialization to make Greece independent of foreign aid. Geological surveys searching for iron, nickel, and chrome were conducted. There were efforts by the Americans to “reclaim” alkali “wasteland” to enable rice to grow for production by building irrigation and drainage ditches, to level the ground and border the fields. Many swamps and lakes were drained and virgin soils were cultivated. Thousands of mules, donkeys, cows, sheep and other animals were imported with American aid (American Aid to Greece: 1945-1951. Economic Cooperation administration Mission to Greece (Marshall Plan), June 1951). Production of hybrid corn, fruit and forest tree seedlings and other root stock for Greece’s vineyards and orchards was launched.

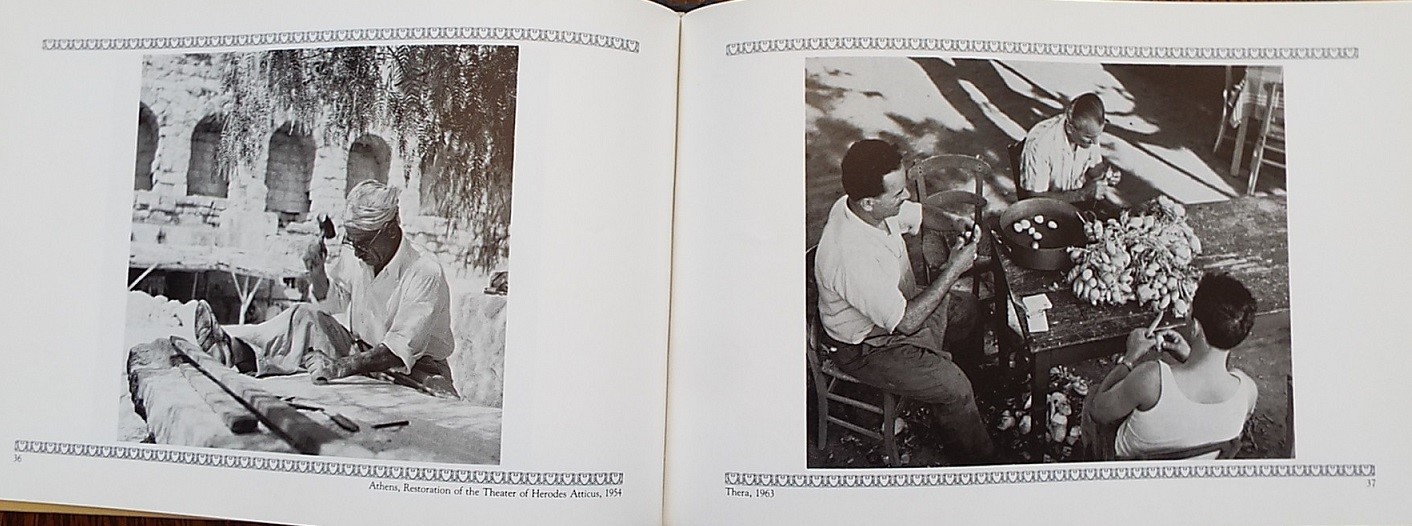

Train tracks, electrical power plants, and airports and ports were built, and the Corinth Canal, destroyed by the German Nazis, was reconstructed and reopened. The tourism sector was also given a boost with museums repaired and antiquities restored. Production was begun of cement, phosphate fertilizers, plastics, paints, dyes, leather goods, paper products, sulfuric acid, glass, textiles thanks to American aid.

The Report describes the people of Greece as being antagonistic towards industries because they viewed industrialists as rich, so they imposed several levies and laws further complicating industrialization (Final Report of AMAG. Field Service American Mission for Aid to Greece by Herbert P. Lansdale, January-October 1948. Athens: American Mission for Aid to Greece, 1948, Minutes, January 27, 1948, p. 16). Other observations made by the Report from the conference on February 24, 25, 26 1948 says that “The Greeks have a peculiar psychology” (Final Report of AMAG. Field Service American Mission for Aid to Greece by Herbert P. Lansdale, January-October 1948. Athens: American Mission for Aid to Greece, 1948, February 24, 25, and 26, 1948, p. 3). An example it gives is that if books are to be distributed, they will also be sent to a blind man who would have no use for them, presumably for equity reasons.

The AMAG Report expressed concerns about Greek exports. For example, it says that Evia (Euboea) had a huge wine surplus but no place to export its wine. Wool, tomato paste, jams, figs, tobacco were slated for export, but Greeks allegedly did not want to part with their lemons and oranges, which were important to its local population. Rumors that cheaper oil was sold as Kalamata olive oil stopped export of olive oil. Export of licorice root was not successful because of the high price. It was also concluded that the salt mines were government owned, but no export was conducted and that the pits did not operate at full capacity.

The cultivation and exploitation of land in Greece was not new. Allaire Stallsmith’s study of Crete is instructive (Allaire B. Stallsmith. “Between Venice and Istanbul: Colonial Landscapes in Early Modern Greece.” One Colony, Two Mother Cities: Cretan Agriculture under Venetian and Ottoman Rule, Hesperia Supplements 40 (2007), pp. 151-171). During the Minoan rule the land was pastoral with goats and sheep, during Venetokratia it was grapevines which dominated and during Tourkokratia it was a land of olive trees. The landscape changes according to the political and economic policies of the ruling elite (Allaire B. Stallsmith. “Between Venice and Istanbul: Colonial Landscapes in Early Modern Greece.” One Colony, Two Mother Cities: Cretan Agriculture under Venetian and Ottoman Rule, Hesperia Supplements 40 (2007), p. 153). The staples of Crete were grain, olives, and grapes. Olives and olive oil were not only food because of their fat content, but oil was also the major lubricant, soap, and lamp fuel. Cretan wine kept longer than the dry wines of Italy and France. Wheat was a major crop of Crete. In Eastern Crete during the modern period the land also saw major changes; during the late Ottoman period grain was planted, after WWII grapes, and in the late 20th c. olive trees (Allaire B. Stallsmith. “Between Venice and Istanbul: Colonial Landscapes in Early Modern Greece.” One Colony, Two Mother Cities: Cretan Agriculture under Venetian and Ottoman Rule, Hesperia Supplements 40 (2007), p. 167). The death knell of the Cretan wine trade was the invention of the bottle and cork which could keep dry wines fresh longer, the loss of a skilled agricultural population, and wartime destruction of Cretan vineyards. Corruption, ineffective administration, taxes, crop failures contributed to the loss of wheat production and export by both the Venetians and Ottomans (Allaire B. Stallsmith. “Between Venice and Istanbul: Colonial Landscapes in Early Modern Greece.” One Colony, Two Mother Cities: Cretan Agriculture under Venetian and Ottoman Rule, Hesperia Supplements 40 (2007), p. 168).

In addition to infrastructure and agriculture, the U.S. provided military aid, equipped the Greek armed forces, furnished rations for the navy and police, and provided more than 200,000 soldiers and more than 200,000 tons of petroleum products. The AMAG Report also asserts that everyone in northern Greece is “always asking for guns” and heavy artillery. The Report states that in 1947 Greece faced communist guerilla warfare aided also from abroad, especially from Albania, Bulgaria and former Yugoslavia. This is blamed for leading to inflation since farmers were afraid to plant crops that could be destroyed, and businessmen feared investing in products that also might be destroyed.

The Report recounts that there were conspiracy theories. One claim made was that the U.S. did not have any desire to end the fighting, but wanted it instead to drag on for years because the U.S. needed Greece as a military base, and that the U.S. was preparing to fight Greece (Final Report of AMAG. Field Service American Mission for Aid to Greece by Herbert P. Lansdale, January-October 1948. Athens: American Mission for Aid to Greece, 1948, Minutes from Conference, January 27, 1948, pp. 1-2). Another attempt at propaganda, according to the Report, was that 12,000 children had been abducted. Some children were abducted and “dumped” by communist insurrectionists, but the veracity of the numbers was debated.

American “propaganda” was administered through the United States Information Service (later Agency), USIS, in Athens which had a small library of use mostly by the staff to answer questions and offer information about the U.S. with local employees plus five American staff members. In addition to a library, USIS had press, radio, photo sections and a Salonika office. Press releases went out to all radio stations in Athens, and they were airmailed to all 76 daily newspapers in Greece.

In addition to agriculture, the Report examined several other sectors and argued that the labor movement was disorganized after the Metaxas dictatorship in 1936, the Albanian War, and Italian and German occupations. Trade unionists are described as “communists and fellow travelers.” Greece had no laws against child labor at that time, so children were relied upon for the support of their families. Lansdale’s report further speaks of too many civil servants in Greek administrative centers, so there were negotiations to reduce the staff and increase the work week from 30 to 40 hours a week. The Mission also worked on pension reforms. There was a shortage of technical manpower and a need for medical personnel for an inadequate health care system to care for people who were suffering from starvation and tuberculosis (need to provide vaccines), and malaria. There was one case of leprosy reported in a village on Crete. Health centers and hospitals were built and American aid supported the education of nurses and doctors. A secretarial school was established in Salonika and equipment for an artificial limb factory also in Salonika was provided by the U.S.

Greek women had limited suffrage at this time based on literacy and age. The Mission supported a move towards making voting almost on a par with that of men. “The proposed action would undoubtedly be pleasing to the women of the world” (Weekly Report of the ECA Mission to Greece and the American Mission for Aid to Greece, no. 23, June 10, 1949, p. 6). The female half of Greece achieved full suffrage in 1952, “only” 131 years after Greek Independence.

Bruce Lansdale concluded that the period immediately after WWII was a turning point in Greek village life, changing from subsistence farming to an agricultural society, if not yet a fully industrial one (Master Farmer: Teaching Small Farmers Management. Bruce M. Lansdale. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1986, p. 17).

Some of our maps were included in an exhibition at Princeton University, December 2022, curated by Professor Richard Talbert, UNC. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/1c511e31e91346af8181854108934e9d