By: Kevin Grace

One of the most in-the-news phrases of this past year has been “fake news.” Every political point of view has employed it to the point where the first reactions among readers and listeners to current events has a question in mind, “Is this real information?” And in times of political or social stress, there is a mounting trepidation over who controls information, or, who preserves it. Librarians are often in the forefront of acquiring information, protecting it from those who would alter or destroy it, and preserving it for now and for the future. The sources of information, of knowledge, continue to grow exponentially and in our rapidly changing technological world, much of it disappears. As websites continue to grow – and to disappear through political exigencies – the expertise of librarians and archivists are called upon, a recent example of which is illustrated in a science article on web discovery and preservation: https://apps.sciencefriday.com/data/librarians.html.

One of the most in-the-news phrases of this past year has been “fake news.” Every political point of view has employed it to the point where the first reactions among readers and listeners to current events has a question in mind, “Is this real information?” And in times of political or social stress, there is a mounting trepidation over who controls information, or, who preserves it. Librarians are often in the forefront of acquiring information, protecting it from those who would alter or destroy it, and preserving it for now and for the future. The sources of information, of knowledge, continue to grow exponentially and in our rapidly changing technological world, much of it disappears. As websites continue to grow – and to disappear through political exigencies – the expertise of librarians and archivists are called upon, a recent example of which is illustrated in a science article on web discovery and preservation: https://apps.sciencefriday.com/data/librarians.html.

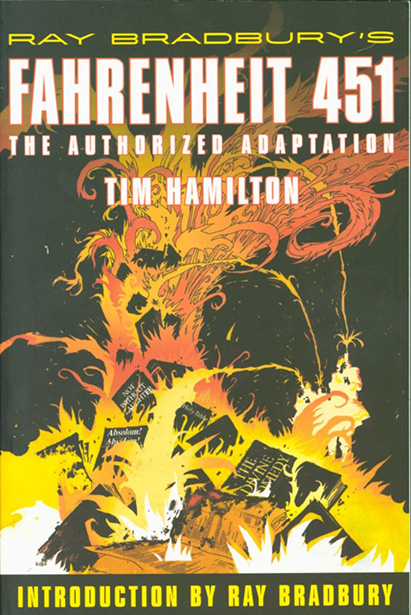

Concomitant with the control of information and knowledge is the treatment of that control in fiction, creating a literary apocalyptic and dystopian culture that has at its heart the fear of libraries and reading, of the use of books. The most familiar novel in this genre, of course, is Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 in which firemen invade homes not to put out fires, but rather to start them as they burn the books they find, the action of a government afraid of its citizens having access to knowledge and understanding that might be at odds with government policy. In the end, books are preserved by the distribution of passages for memorization by those who oppose the government, the hope being that someday in a better time, those memories can be reconstituted in some fashion as the written word.

Concomitant with the control of information and knowledge is the treatment of that control in fiction, creating a literary apocalyptic and dystopian culture that has at its heart the fear of libraries and reading, of the use of books. The most familiar novel in this genre, of course, is Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 in which firemen invade homes not to put out fires, but rather to start them as they burn the books they find, the action of a government afraid of its citizens having access to knowledge and understanding that might be at odds with government policy. In the end, books are preserved by the distribution of passages for memorization by those who oppose the government, the hope being that someday in a better time, those memories can be reconstituted in some fashion as the written word.

Bradbury’s wrote his novel in 1953 during the Cold War, almost three generations ago. But in the past four or five decades, in our generation and that of our children, dozens of dystopian novels and stories have been published, with many of them written for the young adult demographic, and many of them experimental in form or function. For example, in Russell Hoban’s seminal post-apocalyptic novel written in 1980, Riddley Walker, the title character of Ridley is a young boy coming of age in an England which is centuries beyond books and reading. Because Hoban wrote it with an ear to the spoken word rather than a written one, it is a difficult novel to read silently to oneself and is, in fact, much more intelligible and rewarding to read aloud. In brief, young Riddley is trying to recapture a lost literate and civilized England by telling the stories he remembers in a voice that has bastardized the pronunciation of proper names and place names to what is only remembered as  things heard by ear. There are no books and so there is a community fear of Riddley’s trying to write things down, in other words, to make books again. Most of his storytelling is through puppetry, an age-old and accepted tradition of recounting political and historical events. Hoban’s novel has never been filmed but we get a glimpse of how this fear of books is conveyed through the various stage productions of the novel. The book as play features masked actors or marionettes in dark and earth tone clothing and head coverings. Their eyes are dark holes, their expressions are blank. In this visual costuming the effect is to convey that there is an ignorance of books and there is a fear of literacy. It is the general fear of what has become the unknown. The stage sets and costumes draw the audience into a world of controlled access to history.

things heard by ear. There are no books and so there is a community fear of Riddley’s trying to write things down, in other words, to make books again. Most of his storytelling is through puppetry, an age-old and accepted tradition of recounting political and historical events. Hoban’s novel has never been filmed but we get a glimpse of how this fear of books is conveyed through the various stage productions of the novel. The book as play features masked actors or marionettes in dark and earth tone clothing and head coverings. Their eyes are dark holes, their expressions are blank. In this visual costuming the effect is to convey that there is an ignorance of books and there is a fear of literacy. It is the general fear of what has become the unknown. The stage sets and costumes draw the audience into a world of controlled access to history.

And it is that aspect of “control” which is key to understanding the position of libraries and repositories, books and reading, and information and knowledge in dystopian and post-apocalyptic culture. Totalitarian governments must control people absolutely. Even the feeling or threat of the loss of this control gives rise to fear – fear that power will be taken away, fear of not understanding the mechanisms – or the manifestations of how this can be done. This develops into a fear of what books contain and of the books themselves. If anybody can possess them and anyone can read them, anyone can have the power of knowledge and power cannot be shared in a dystopian society. The logical action in such matters is to deny access – this is done by sequestering books and libraries or by outright destroying them. Visually, this was  done in the science fiction television series, The Twilight Zone, broadcast from 1959 to 1964 in its first incarnation.

done in the science fiction television series, The Twilight Zone, broadcast from 1959 to 1964 in its first incarnation.

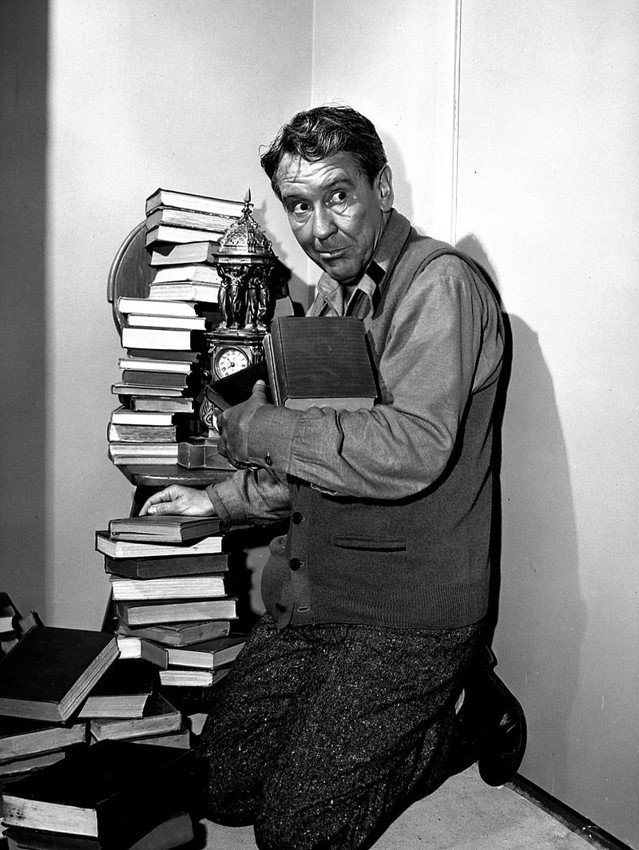

As examples in two episodes that featured the character actor Burgess Meredith, he experiences a deep well of loss when the richness of a library’s holdings can no longer be accessed because of a bizarre twist of fate in “Time Enough at Last,” and in “The Obsolete Man” he is condemned and terminated by an authoritarian government for withholding books and information, and, for advocating their importance. In the former, first shown on television in 1959, Meredith is Henry Bemis, a mild-mannered and henpecked bank teller who is so enthralled with the beauty of love of reading that he neglects his banking responsibilities during the day and at night must hide from his domineering and shrewish wife his simple reading of a newspaper. His thick-lensed glasses give him an air of bewilderment and his blindness without them hides him from the daily activities of the world around him. One day, he secrets a book beneath his coat and absconds to the below- ground and well-fortified bank vault so he may read during his lunch hour. He is oblivious to the devastation which takes place on the surface, that is, an atomic bomb that wipes out all life. When he finally ventures out into the street, stepping over rubble and waste he comes upon the public library. The building itself is virtually destroyed but the books remain undamaged and Henry believes he has finally attained paradise – no one to admonish him for reading and all the time in the world to do so. As he sits  down to read, however, he stumbles and his glasses fall off his face. They are smashed. He is blind. And in this post-apocalyptic society now, the books are useless because there is no one to read them. His worst fears have come true – time enough to read and never being able again to enjoy his beloved books.

down to read, however, he stumbles and his glasses fall off his face. They are smashed. He is blind. And in this post-apocalyptic society now, the books are useless because there is no one to read them. His worst fears have come true – time enough to read and never being able again to enjoy his beloved books.

In the other episode, “The Obsolete Man,” broadcast two years later in 1961, Meredith plays Romney Wordsworth, a librarian who is put on trial because the government has eliminated books and all works of literature as useless. Wordsworth’s belief in an almighty power also leads him to be his trial. His offenses are punishable by death. In a Kafkaesque trial, Wordsworth makes an eloquent case for the need of books, but it is no use. He is condemned, but in given a final say in his execution, he chooses that it be televised live to the nation. When the Chancellor, the man who has passed sentence on him, attends Wordsworth in his home where he is surrounded by books, Wordsworth is very calm and accepting of his impending death. And, he locks both of them inside and informs the Chancellor that a bomb will go off and kill them both. Wordsworth produces his hidden, forbidden Bible. The Chancellor turns cowardly and begs, “in the name of God” to be spared. Wordsworth releases him from the room but as the Chancellor escapes the bomb explodes and Wordsworth, the man of books and words, calmly and stoically dies. The Chancellor is then condemned to death by the State for his display of cowardice.

The visual effect of these episodes was filmed in the common black and white television technology of the time and in viewing them today, the starkness appears rich and provocative. The cold detachment of those who do not understand or appreciate the power of the written word is almost palpable, and the casual authoritarian dismissal of the need for books comes about because those who rule in societies such as those presented here do not welcome anything that threatens their status.

The visual effect of these episodes was filmed in the common black and white television technology of the time and in viewing them today, the starkness appears rich and provocative. The cold detachment of those who do not understand or appreciate the power of the written word is almost palpable, and the casual authoritarian dismissal of the need for books comes about because those who rule in societies such as those presented here do not welcome anything that threatens their status.

These themes of detachment and disregard are mild compared to that expressed in Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. As a worldwide classic, its readers are acutely aware of the government’s active pursuit of books in order to burn them and eliminate them forever. And, the cover art and illustrations of the many editions emphasize not only authorities putting books to the torch in a new information-controlled world, but also conveyed through illustration is a tremendous sense of loss and despair. Yet, people read and remember.

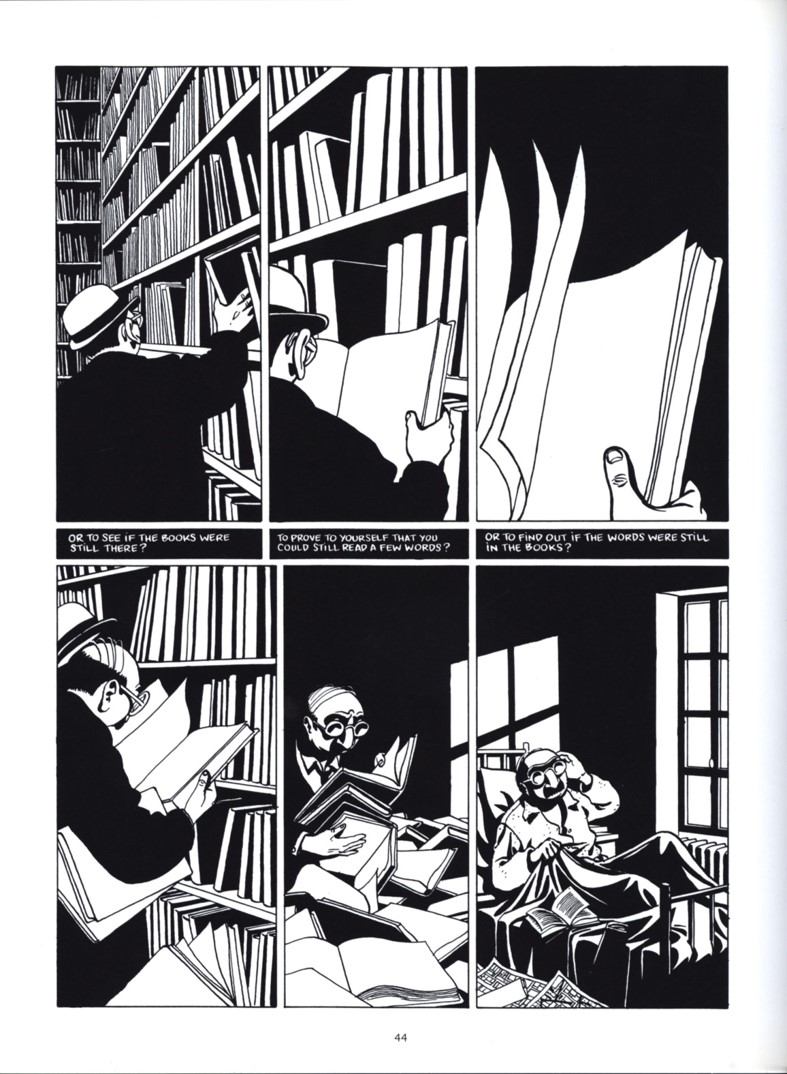

In a graphic novel, Dead Memory, published in 2004, there are eloquently rendered black and white illustrations of a city slowly wiping out books, libraries, and memory through the nightly physical shifting of buildings to control neighborhoods and the interactions of people. The book is reminiscent of the wordless graphic novels of Belgian Frans Masreel and American Lynd Ward in their woodcuts from the 1920s and 1930s that conveyed the dismal nature of man’s existence in an unyielding urban environment. The disconnection with urban life in its dark streets and aloof  strangers speaks of the need to dismiss books and reading because the failure to do so would cause individuals to want more out of life than a government is willing to give them. For the character, who is an urban planner and architect, to read means you are still alive, that you still function as a passionate member of society. As he states after discovering a computer has been programmed to make the municipal changes and confronting the machine, “I can imagine the silence settling over the city. That silence is something else you’ve forgotten, with images breaking off where words end. How long will you be able to hold out?”

strangers speaks of the need to dismiss books and reading because the failure to do so would cause individuals to want more out of life than a government is willing to give them. For the character, who is an urban planner and architect, to read means you are still alive, that you still function as a passionate member of society. As he states after discovering a computer has been programmed to make the municipal changes and confronting the machine, “I can imagine the silence settling over the city. That silence is something else you’ve forgotten, with images breaking off where words end. How long will you be able to hold out?”

This theme of cities and the subjugation of libraries and archives is carried further in the cover art of Carrie Patel’s recent book, The Buried Life (2015), there is an underground city called “Recoletta” that houses the Directorate of Preservation, a top secret repository of historical documents – in other words, where the government hides its secrets and the lies it prepares for citizens – they control the “word”, they control knowledge. Toby Ball’s The Vaults (2014) is similar in scope. It takes place in 1930s America, and it also involves underground knowledge storage centers where only the select may discover the truth.

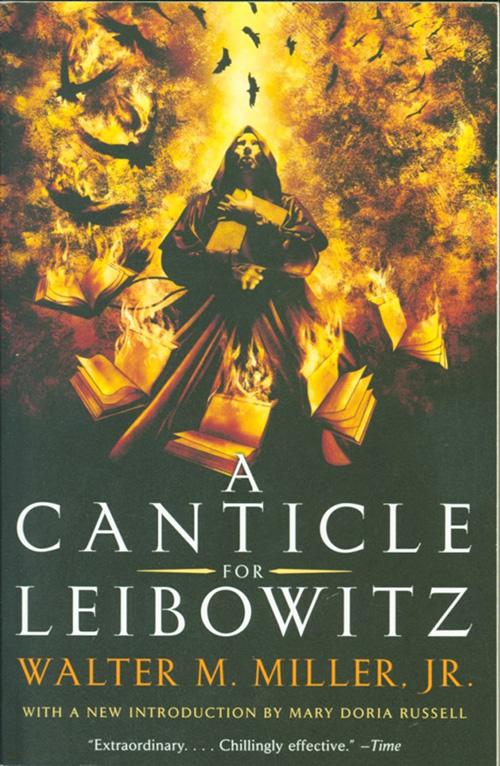

In two other classic dystopian novels, Walter Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959) and Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange (1962), the cover art demonstrates two different approaches to the concepts of books in a dystopian age, one in which the book is sacred and the other in  which a character’s grimacing scream points to the dysfunctional characters within the book’s pages. Both are luridly colored, fraught with fire and destruction. In the case of the Burgess novel, when it was adapted as a film there is a violent scene that takes place in a home library where the owners are beaten and violated, surrounded by their precious books.

which a character’s grimacing scream points to the dysfunctional characters within the book’s pages. Both are luridly colored, fraught with fire and destruction. In the case of the Burgess novel, when it was adapted as a film there is a violent scene that takes place in a home library where the owners are beaten and violated, surrounded by their precious books.

The home library aspect is repeated in the modern classic, V for Vendetta (1989), again in the film version where the character, V, maintains a hidden storehouse of books in his lair, safe from the hands and eyes of the totalitarian regime as he plots his revolution to the rhyme of “Remember, Remember, the 5th of November.” His maintenance of his books illustrates his belief that he is a learned man who can overthrow those who are not. The film, The Book of Eli 2010), carries somewhat the same theme of A Canticle for Leibowitz, in that holy books created by human beings must at all costs be preserved in a post-apocalyptic society because it rallies the human spirit and maintains a culture of belief.

With these works, as well as other fiction, graphic novels, and films, the fear, anger, and desperation in being denied access to books and reading through authoritarian control is depicted graphically through cover art and textual illustration, as well as the colors, or lack thereof, in  cinematic treatments. In dystopian culture, the visual introduction to these characteristics is paired with textual understanding, and as access to information evolves (or, devolves) in the 21st century, contemporary novels increasingly explore the control of libraries, archives, bookstores, and other repositories of heritage and memory. In the banning of books, the burning of manuscripts, the deletion of databases, there is witness to the rending of the social fabric and the attempts to thwart the opposition to repair it.

cinematic treatments. In dystopian culture, the visual introduction to these characteristics is paired with textual understanding, and as access to information evolves (or, devolves) in the 21st century, contemporary novels increasingly explore the control of libraries, archives, bookstores, and other repositories of heritage and memory. In the banning of books, the burning of manuscripts, the deletion of databases, there is witness to the rending of the social fabric and the attempts to thwart the opposition to repair it.

In reading these novels and stories, we can ask ourselves four questions: are libraries illustrated as deep, dark, and musty repositories of history and knowledge, either kept safe from governments or kept hidden by governments? Is reading done in a circumspect manner, with words hidden or distressed in cover art? Is the 21st century view of information technology portrayed as sterile, impassive, monolithic environments? Do the flames of government destruction of books graphically reflect the human dilemma in the loss of written testament to liberty? By examining such contemporary novels such as Alena Graedon’s The Word Exchange (2014), Marc-Antoine Mathieu’s graphic novel, Dead Memory (2003), the works of Serbian writer Zoran Živkovic that concern books, and even words, that become missing once someone wishes to read them, Nicolas De Crécy’s illustrations in  Glacial Period (2005) that reveal archaeologists in the future amazed at the literary heritage they excavate and comparing them with each other as well as older dystopian novels, one can trace the societal impact on reader reception to storylines. With the tremendous increase in recent years of publishing-on-demand and other self-published efforts, previously unrecognized writers of such fiction must add to the considerable numbers of dystopian books about libraries and reading. That these authors take this topic of books and libraries as subject matter conveys a cultural awareness of how books and reading habits are simultaneously celebrated and protected while at the same time sounding a clarion call of warning. Not only literary scholars but general readers as well can ask the fifth and final question, “Why do these attitudes toward reading and libraries flourish and cross cultural boundaries in our modern age?”

Glacial Period (2005) that reveal archaeologists in the future amazed at the literary heritage they excavate and comparing them with each other as well as older dystopian novels, one can trace the societal impact on reader reception to storylines. With the tremendous increase in recent years of publishing-on-demand and other self-published efforts, previously unrecognized writers of such fiction must add to the considerable numbers of dystopian books about libraries and reading. That these authors take this topic of books and libraries as subject matter conveys a cultural awareness of how books and reading habits are simultaneously celebrated and protected while at the same time sounding a clarion call of warning. Not only literary scholars but general readers as well can ask the fifth and final question, “Why do these attitudes toward reading and libraries flourish and cross cultural boundaries in our modern age?”

To learn more about the general history of books, libraries, and reading, visit the Archives & Rare Books Library on the 8th floor of Blegen Library, call ARB at 513.556.1959, email at archives@ucmail.uc.edu, check out the website, http://libraries.uc.edu/arb.html, or follow ARB on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/ArchivesRareBooksLibraryUniversityOfCincinnati.