By: Kevin Grace

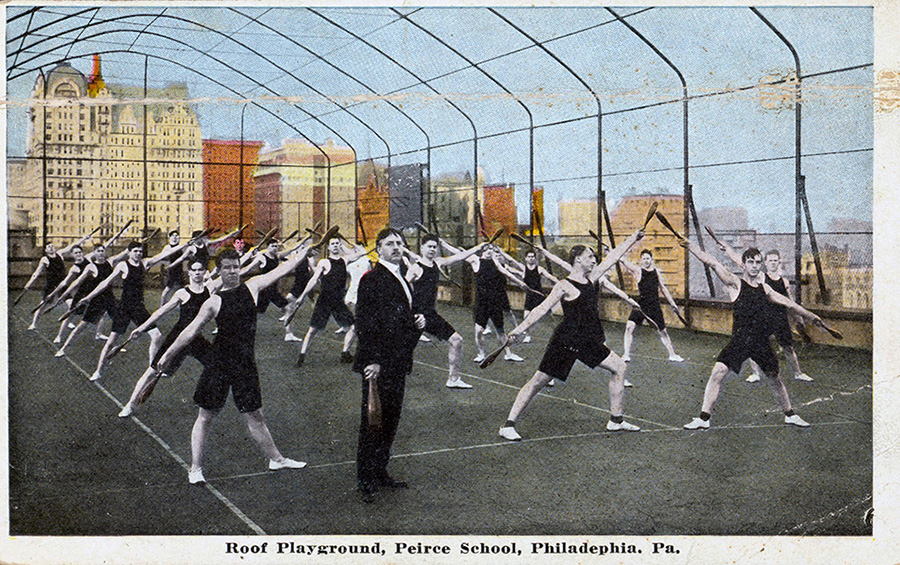

On a hot June day in 1909, thousands of people gathered at the Carthage Fairgrounds just beyond the city limits of Cincinnati. There on the nubby dusty infield of the racetrack, groups of women clad in long dresses divided themselves into squads of threes and fours and faced the spectators. In each hand they held an “Indian club,” a standard piece of gymnasium equipment at the time, and as the crowd watched, the women began a series of intricate, graceful movements, swinging the clubs up from their sides and around their bodies, crisscrossing the clubs in patterns that emphasized coordination and discipline. The demonstration was just one of several exhibits of mass exercises at the quadrennial Turnfest that was hosted by the Cincinnati Turners organizations that year, a fitting location as the American Turner movement was founded by German immigrants in Cincinnati in 1848.

On a hot June day in 1909, thousands of people gathered at the Carthage Fairgrounds just beyond the city limits of Cincinnati. There on the nubby dusty infield of the racetrack, groups of women clad in long dresses divided themselves into squads of threes and fours and faced the spectators. In each hand they held an “Indian club,” a standard piece of gymnasium equipment at the time, and as the crowd watched, the women began a series of intricate, graceful movements, swinging the clubs up from their sides and around their bodies, crisscrossing the clubs in patterns that emphasized coordination and discipline. The demonstration was just one of several exhibits of mass exercises at the quadrennial Turnfest that was hosted by the Cincinnati Turners organizations that year, a fitting location as the American Turner movement was founded by German immigrants in Cincinnati in 1848.

The festival attracted Turner athletes from around the country and around the world, all journeying to Cincinnati as they had to other cities in past years to exhibit the Turner philosophical ideals of physical and mental fitness, and civic responsibility. In the days before the ladies’ exercise with Indian clubs, students in the city’s schools demonstrated the skills they had learned in physical education classes, a mainstay of the public school academic program in Cincinnati. The proper uses of parallel bars, wands and rings, and the pommel horse were performed in front of school officials and Turner judges. It was a program already several decades old, begun in earnest after the Civil War when secondary and primary teachers learned the techniques of physical fitness and health promotion under the leadership of Turner instructors.

In those early years of physical fitness as part of school curricula, America began the so-called “Athletic Revival” in the 1860s with several ethnic and civic organizations in place that promoted physical culture in conjunction with civic mindedness, patriotism, intellectual development, and spiritual growth. The YMCA’s “Muscular Christianity” philosophy is perhaps the best known, but the American Turner movement, along with other ethnicity-based societies such as the Czech Sokols, the Jewish urban settlement houses, the Polish Falcons, and the Swedish gymnastic movement, also promoted the notion of physical development for the public good to achieve an ideal lifestyle.

In those early years of physical fitness as part of school curricula, America began the so-called “Athletic Revival” in the 1860s with several ethnic and civic organizations in place that promoted physical culture in conjunction with civic mindedness, patriotism, intellectual development, and spiritual growth. The YMCA’s “Muscular Christianity” philosophy is perhaps the best known, but the American Turner movement, along with other ethnicity-based societies such as the Czech Sokols, the Jewish urban settlement houses, the Polish Falcons, and the Swedish gymnastic movement, also promoted the notion of physical development for the public good to achieve an ideal lifestyle.

Of the diverse physical education equipment developed in that era, one of the most ubiquitous elements of German American gymnastic work was the Indian club, an exercise tool first brought to European attention by British soldiers who adapted it from a war club used on the Asian subcontinent. As part of calisthenics and gymnastic exercises, the Indian club also had a long life in America from the Civil War era to the 1930s, and was an equipment mainstay not only in a standard physical education regimen, but also as a part of aesthetic demonstrations during turnfeste and in the nation’s school gymnasia.

Once commonly used to exhibit corporal stamina, discipline, teamwork, and beauty of form, the Indian club is little known today except as a curious artifact and as a collectible in the category of American folk art. However, during the Progressive Era, club-swinging was especially important in the gyms, particularly in those cities where Turners held the greatest influence in establishing regular physical education in public schools and teachers’ colleges.

Falling into the general exercise category of “circular strength training,” the use of Indian clubs can be traced in part to ancient Persia and competitions between strongmen. A wrestler, fighter, or weightlifter was call a “Pahlavan,” or “club-swinging strongman.” The use of such clubs built endurance and strength, and contributed to flexibility. Some historians believe the use of regimented club-swinging can even be traced back to the ancient civilizations of Egypt and Greece, in all circumstances used in a militaristic or combative environment.

Circular strength training has always involved a variety of implements, such as the Russian bulava, the Iranian meel, the Okinawan chishi, or the Indian gada. But it is the latter that eventually made its cultural way to America and a place in German American physical education.

Circular strength training has always involved a variety of implements, such as the Russian bulava, the Iranian meel, the Okinawan chishi, or the Indian gada. But it is the latter that eventually made its cultural way to America and a place in German American physical education.

The manipulation of the Indian “gada” or the Indian club, as we know it, was closely observed by British troops in India in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Early ethnographic accounts by missionaries and traveling merchants mention the indigenous population swinging heavy wooden war clubs in intricate and graceful patterns. The performers were noted for their great strength and marvelous body definition. As a war club, the gada was a symbol of temporal power and physical invincibility. Many representations of Hindu deities, especially Vishnu, often depict them holding the gada. The effective use of the club denoted honor and virility.

Officers in the British Army noted the exercises and one commented in the 1850s, “The wonderful club exercise is one of the most effectual kinds of athletic training, known anywhere in common use throughout India. The clubs are of wood, varying in height according to the strength of the person using them, and in length about two feet and a half, and some six or seven inches in diameter at the base, which is level, so as to admit of their standing firmly when placed on the ground, and thus affording great convenience for using them in the swinging positions.”

The military correspondent went on to relate: “The exercise is in great repute among the native soldiery, police, and others whose caste renders them liable to emergencies where great strength of muscle is desirable. The evolutions which the clubs are made to perform, in the hands of one accustomed to their use, are exceedingly graceful, and they vary almost without limit. Beside the great recommendation of simplicity, the Indian Club practice possesses the essential property of expanding the chest and exercising every muscle in the body concurrently.”

And it is this notion of the total workout, indeed aerobics as we know the term now, that would make the swinging of Indian clubs such an attractive calisthenic to incorporate into a nineteenth century physical fitness regimen.

The cultural migration of the sub-continent’s Indian club to England began its journey in the 1850s when it was introduced into the British Army as part of the military drill. At the time it was similar to the so-called “Swedish cure” extension movements that were designed to expand the chest and make muscles supple rather than the concerted exercises used to develop the strength and endurance necessary for military actions. By the time the use of Indian clubs actually reached the gymnasia and clubrooms of Mother England, the Indian club was already being viewed as a flexibility and aesthetic tool rather than one of war.

Much of this early history was documented by a man who was largely responsible for introducing the Indian club to American shores. Sim D. Kehoe, who was a proponent of physical fitness and mental health, traveled to England in 1861. There he observed the exercise routines of one Professor Harrison, who claimed to be the strongest man in England and who had enthusiastically adopted the use of Indian clubs as a means to achieve his stature. Kehoe was greatly impressed by the form and discipline of club-swinging and saw in the clubs another method of health promotion, this at an age when there were frequent “cures,” “methods,” “diets,” and “regimens,” in the United States that would rescue complacent Americans from a lethargy brought on by the Industrial Revolution and improvements in the standard of living. In a country that was still largely unsettled in a cultural sense, the various health promotions and fads attempted to instill a sense of moral order as well as physical. Such attitudes would lead, of course, to the Athletic Revival, and the philosophy of Turners and other groups who advocated strong minds, strong bodies, and strong spirits, the latter in either a religious or a community sense.

Much of this early history was documented by a man who was largely responsible for introducing the Indian club to American shores. Sim D. Kehoe, who was a proponent of physical fitness and mental health, traveled to England in 1861. There he observed the exercise routines of one Professor Harrison, who claimed to be the strongest man in England and who had enthusiastically adopted the use of Indian clubs as a means to achieve his stature. Kehoe was greatly impressed by the form and discipline of club-swinging and saw in the clubs another method of health promotion, this at an age when there were frequent “cures,” “methods,” “diets,” and “regimens,” in the United States that would rescue complacent Americans from a lethargy brought on by the Industrial Revolution and improvements in the standard of living. In a country that was still largely unsettled in a cultural sense, the various health promotions and fads attempted to instill a sense of moral order as well as physical. Such attitudes would lead, of course, to the Athletic Revival, and the philosophy of Turners and other groups who advocated strong minds, strong bodies, and strong spirits, the latter in either a religious or a community sense.

Back home in America, Kehoe reshaped the Indian club, keeping its basic form but adding dimensions that would make it a useful apparatus for men, women, and children. He arranged with an athletic goods company to manufacture them, and in 1866 he published the first American manual on Indian club-swinging, The Indian Club Exercise. His promotion of the book and its techniques even led him to send clubs in April 1866 to General Ulysses S. Grant, who kindly replied, “I have the pleasure of acknowledging the receipt of a full set of rosewood Dumb-Bells and Indian Clubs, of your manufacture. They are of the nicest workmanship. Please accept my thanks for your thus remembering me, and particularly my boys, who I know will take great delight as well as receive benefit in using them.”

In shape not unlike our experiences with bowling pins, duckpins, and juggler’s clubs, the American-style clubs were often made of either rosewood, as the gift to Grant was, or maple, mahogany, or walnut. They were turned on a lathe and manufactured in matching pairs because the exercises most often used a series of movements with a club in each hand. The clubs varied in length and weight, the so-called “short clubs” being favored for women and children, and the longer ones (the length of a man’s arm was a guide) for men. The most common ones for ordinary exercise were about twelve inches in length and one-half pound for children to eighteen inches and one and a half pounds for women, and twenty inches and two and a half pounds for men. Because of the beautiful woods used in their manufacture, Indian clubs also possessed an aesthetic sense of design along with the utilitarianism, and clubs owned by individuals were often stained, painted, or carved to reflect personal tastes.

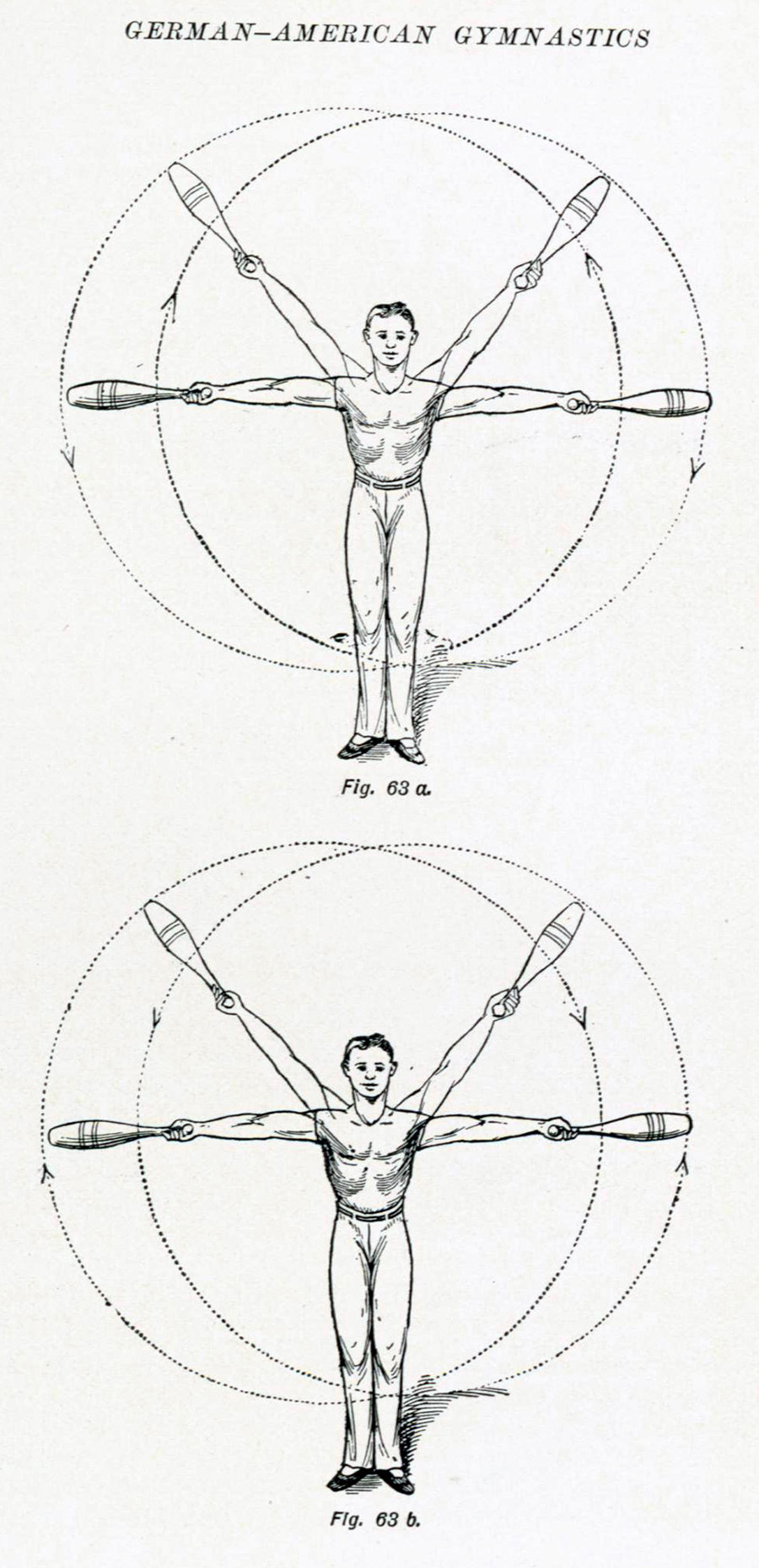

Kehoe’s instructional manual that accompanied the clubs was based on an illustrated alphabetic series of movements that led to a synchronized display of club prowess. Position A leads into position B which in turn combines with positions C and D to produce a distinct form. With clubs at the side, for instance, the individual would raise them above the shoulder, rotate them above the head, bring them down behind the back, and then back to the starting position. The clubs were weighted differently for men, ladies, and school children and the synchronized individual forms they were taught were integrated into a mass group exercise. On a large scale, the Indian club calisthenics could be quite the spectacle.

Kehoe’s instructional manual that accompanied the clubs was based on an illustrated alphabetic series of movements that led to a synchronized display of club prowess. Position A leads into position B which in turn combines with positions C and D to produce a distinct form. With clubs at the side, for instance, the individual would raise them above the shoulder, rotate them above the head, bring them down behind the back, and then back to the starting position. The clubs were weighted differently for men, ladies, and school children and the synchronized individual forms they were taught were integrated into a mass group exercise. On a large scale, the Indian club calisthenics could be quite the spectacle.

According to Kehoe, there were two divisions to education: the physical and the moral. After some consideration, he added a third: intellectual. He stated: “the organized system of man constitutes the machinery with which alone his mind operates during their connection as soul and body. Improve the apparatus, then, and you facilitate and improve the work which the mind performs with it…each works and produces with a degree of perfection corresponding to that of the instrument it employs. Hence physical education is far more important than is commonly imagined.” Yet he was speaking at a time when Americans found themselves more distanced – both physically and emotionally – from the requirements of proper exercise. Addressing this dilemma, Kehoe said, “To those, then, who say they have no time for exercise, we heartily recommend the Indian clubs, which, in connection with a daily walk of a few miles, will be just exactly what is required to secure physical perfection and muscular strength. His message was clear: neglect the body, impoverish the mind. Exercise the muscles, and the stimulus is there to nourish the mind and spirit as well. He cited the example of a young German American artist, Frederick Kuner of New York, who through his exercise with Indian clubs attained proportional development and a “manly form.” Presumably, the exercise led to Herr Kuner’s development of the artistic temperament as well.

Kehoe’s advocacy of Indian club exercise met with considerable favor in the years after the Civil War. The horror of the war had forced some considerable reflection on the part of Americans as to their national purpose and their individual place in fulfilling it. Building upon the antebelleum approach to health and fitness, the postbellum years saw the construction of more gymnasia and exercise clubs, along with a new YMCA philosophy that mandated the construction of a gymnasium with any new building plan. A large part of this growing emphasis on physical culture was due in large measure as well to the construction of Turners’ halls in cities across the country. The Turner ideals of civic responsiveness, mental acuity, physical fitness, and military preparedness were perfect responses to a piece of equipment such as the Indian club. There was a bellicose aspect to it befitting of warriors, there was a discipline to it that mirrored an adherence to cultural values, and there was an aesthetic grace to the use of the club in gymnastics that was mentally stimulating.

Because of the influence several Turners organizations held in urban affairs and the politics of education, there was an effort after the war to make physical education a regular part of the school curriculum. In Cincinnati, for example, Louis Graeser convinced the board of education as early as 1860 that physical fitness and health promotion should be a vital part of the city’s educational programs. Convinced by his argument, the Cincinnati board appointed Graeser the “Superintendent of Gymnastics,” a position he held for the next thirty years. And Rufus King, the school superintendent, noted in a report, “…with suitable time for rest and recreation, teachers and pupils return to the duties of the school-room with pleasure instead of dislike…activity and cheerful zeal take the place of languor and indifference; mind acts upon mind with greater vividness and comprehensiveness.” King was a prominent figure in local education. In addition to being one of the movers and shakers of the public library, he served as the first chairman of board of directors of the new University of Cincinnati in 1870 and later served as dean of the College of Law. With King’s support, Graeser saw his effort followed by a similar one in Chicago in 1866 and by the 1880s, most cities, especially those with heavy German populations like Cincinnati, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, Baltimore, and Pittsburgh, created standard physical education programs in both primary and secondary schools.

Because of the influence several Turners organizations held in urban affairs and the politics of education, there was an effort after the war to make physical education a regular part of the school curriculum. In Cincinnati, for example, Louis Graeser convinced the board of education as early as 1860 that physical fitness and health promotion should be a vital part of the city’s educational programs. Convinced by his argument, the Cincinnati board appointed Graeser the “Superintendent of Gymnastics,” a position he held for the next thirty years. And Rufus King, the school superintendent, noted in a report, “…with suitable time for rest and recreation, teachers and pupils return to the duties of the school-room with pleasure instead of dislike…activity and cheerful zeal take the place of languor and indifference; mind acts upon mind with greater vividness and comprehensiveness.” King was a prominent figure in local education. In addition to being one of the movers and shakers of the public library, he served as the first chairman of board of directors of the new University of Cincinnati in 1870 and later served as dean of the College of Law. With King’s support, Graeser saw his effort followed by a similar one in Chicago in 1866 and by the 1880s, most cities, especially those with heavy German populations like Cincinnati, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, Baltimore, and Pittsburgh, created standard physical education programs in both primary and secondary schools.

With the beginning of the Progressive Era in the late 1870s and early 1880s, there was even more of an impetus in society to better its educational system, and in a fashion make the curricula all-embracing for the needs of students. For Americans, this era signaled the promise and potential of social betterment, from the fight against corrupt urban politics, to the battles against poolrooms, saloons, urban crime and squalid conditions of hygiene. Success rested in part with education in the schools, and gave rise to a new vision of professional educators. In dealing with ethnically-diverse urban populations of children facing the new demands of societies, education could not be left in the hands of amateurs. John Dewey of the University of Chicago and Columbia University was the foremost advocate of Progressive Era ideals in education and he saw the classroom as a place where the teacher took the student’s own background and life experiences and used that as an educational tool to send him or her out into an industrialized world.

When physical education programs established as a necessary part of health promotion, the German American influence fit perfectly with Progressive Era ideology. Turner physical fitness instructors who had become politically connected with school systems on both the local level and in colleges and universities began writing textbooks detailing the German system of gymnastics, including detailed chapters on various apparatus that included the Indian Club. Mind and Body, a monthly journal devoted to German gymnastic methods, was published in Milwaukee in the late 19th century, edited by Karl Kroh of the Cook County, Illinois Normal School, Hans Ballin of the Normal School of the North American Gymnastic Union in Milwaukee, and William Stecher, the St. Louis-based secretary of the North American Gymnastic Union. This union was a division of the Nordamerikanischer Turnerbund and led the way in promoting German gymnastics in education. In 1894, the union also published an English translation by A.B.C. Biewend of F.A. Schmidt’s seminal book, Physical Exercises and Their Beneficial Influence: A Short Synopsis of the German System of Gymnastics for Teachers of Gymnastics and All Friends of Physical Culture.

In 1895, the aforementioned William Stecher published his own textbook anthology of chapters on various aspects of gymnastics. Drawing upon the country’s German American experts, Stecher divided his textbook into areas of instruction. F. W. Froehlich of St. Louis authored the chapter on “Exercises with Clubs,” providing detailed lessons on club swinging. The lessons were grouped into categories of difficulty, and only after having mastered them in order could one be considered adept in the art of club-swinging.

In 1895, the aforementioned William Stecher published his own textbook anthology of chapters on various aspects of gymnastics. Drawing upon the country’s German American experts, Stecher divided his textbook into areas of instruction. F. W. Froehlich of St. Louis authored the chapter on “Exercises with Clubs,” providing detailed lessons on club swinging. The lessons were grouped into categories of difficulty, and only after having mastered them in order could one be considered adept in the art of club-swinging.

Stecher followed this book in 1915 with another manual, complete with photographs of both girls and boys exercising with the clubs. Indian club exercise manuals proliferated in the new twentieth century. William Schatz of Temple University wrote one for normal students, Luther Gulick, director of the YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts,and a former president of the American Physical Education Society, included clubs in his series of manuals on “Ten Minutes’ Exercise,” A.F. Jenkin of the German Gymnastic Society co-authored another one, and in J.H. Dougherty’s manual published as a part of Spalding’s Athletic Library, he had this to say about club-swinging: “There is a fascination about this exercise that grows on one with his proficiency. The exercise or strain is rarely felt after the primary motions are mastered.”

Dougherty’s sentiments were in line with the whole German American approach to calisthenics: a fascination with the beauty of human movement. Even another text, Aesthetic Dancing, published in 1915 by Emil Rath, the director of the Normal College of the North American Gymnastic Union, emphasized the achievement of fitness and grace through comely movement. In that regard, the Indian club was the loftiest of the tools used in demonstrations. As individuals swung the clubs about, the spectator could see not only the artistic beauty of the wooden club, but that of the athlete as well. It became a pageant of form, and at one point there was even available for exhibitions an Indian club made of metal that had small circles cut into it. Inside was a light bulb attached to a forty-foot silk cord that was plugged into an outlet. Manufactured by the John Creelman Company of New York, the club was “just the thing for professional and amateur entertainments. Swung in the dark, the effect is startling and pleasing.” The cost was $7.00, and one hopes the movements were not so intricate that a practitionere would get tangled in the cord and ruin the effect.

As a piece of equipment in physical exercise, the popularity of the Indian club would, for the most part, disappear after World War I when the nature of urban and national politics caused a national retrenchment in demonstrating many things that were of German American influence. Use of the club would stagger on through the 1920s but virtually disappear after that. A number of reasons can be given, including the post-war decrease in Turner membership, but also a change in exercise philosophy that centered not so much on group or individual calisthenics as it did on team or individual play in which the aim was to score a goal or score points, and thus win. Not coincidentally, this was the time when basketball emerged as a strong urban sport. Politically, the German American influence in public education was waning and with it, its traditional forms of exercise. And so went the Indian club. Today in the twenty-first century, there is a revival of sorts and a renewed interest in the individual workout from pilates to step aerobics to weightlifting to swinging clubs or small dumb-bells. One can even order a modern version of the Indian club through a distributor of fitness equipment.