As part of the Ohio Network of American History Research Centers, the Archives and Rare Books Library holds Hamilton County Morgue records spanning the years 1887-1930. Despite the rather gloomy first impression that these 21 volumes may give, they offer valuable information for use in social research.

As part of the Ohio Network of American History Research Centers, the Archives and Rare Books Library holds Hamilton County Morgue records spanning the years 1887-1930. Despite the rather gloomy first impression that these 21 volumes may give, they offer valuable information for use in social research.

The office of Coroner is one of the oldest in the State of Ohio, dating back to a 1788 ordinance of the Northwest Territory, which provided that the Governor appoint a coroner for each county to serve a term of two years. The purpose of the Coroner in the early days was to preside over inquests held over bodies believed to have been victims of criminal violence. Ohio’s first constitution, drafted in 1802, also provided for a Coroner in each county to be elected for a term of two years. In 1921 constitutional changes first gave the Coroner authority to perform autopsies under the direction of the county prosecutor in addition to holding inquests, and required the Coroner to be a practicing physician in good standing.

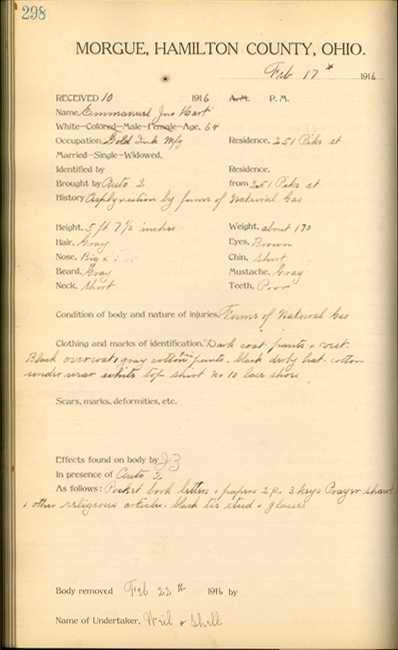

Bodies were taken to the morgue for various reasons, such as suspicion of murder or suicide, accidental deaths, unidentified or unclaimed bodies, or death under unknown or otherwise suspicious circumstances. To name just a few of the many subject areas to which they may be applied, the records can aid in revealing trends in economic depressions, workplace conditions, crime patterns, and infant survival rates. Morgue records also offer a more personal look at the deceased than a death record of the same era.

The records in this collection cover both the time period when the Coroner was only responsible for inquests as well as when autopsies were performed. While the information collected changed over the years, what may be found in the morgue records include: the date and time the body was found and where, name of deceased if known, marital status, place of residence, name of relative or friend and residence, sex, race, age, height, weight, hair and eye color, condition of teeth and neck, existence of facial hair, marks on the body, clothing, probable cause of death, effects found on person and around the body, person who brought body to morgue, who found body, and who buried body. Some records are also accompanied by letters from next-of-kin or public officials that offer more information on the deceased’s situation.

The collection is accessioned as ON-73-38a.

– Janice Schulz