By: Angela Vanderbilt

In the spring of 1916, the citizens of Cincinnati voted in favor of the $6 million bond issue approved by City Council for construction of the “Pearl Street Belt Line,” a rapid transit loop that was to provide a solution to the congested traffic patterns in-and-out of downtown Cincinnati at the turn of the 20th century.

The $6 million budget was based on average costs for construction materials such as reinforced steel, wood and cement, as well as equipment, machinery, surveying and labor, all of which had been estimated based on the original 1915 design scheme. The subway project was scheduled to move forward in the spring of 1917, but would be put on hold as America entered World War I that June.

Due to government restrictions on the issuing of bonds, funds would not be available until after the war, at which time the Rapid Transit Commission quickly discovered that the cost for construction materials had doubled. The cost for reinforced steel in 1915 was $55 per ton; in 1919, it cost $105 per ton. Reinforced concrete averaged $8 per cubic yard in 1915, but rose to $16 per cubic yard in 1919. Excavation costs also increased, from $.80 per cubic yard in 1915 to $1.25 per cubic yard in 1919. Adjustments to the route were made to reduce costs, but further changes were necessary and the eastern portion of the line was eliminated, as well as one tunnel and two stations in the downtown area. Despite these changes, an additional $10.6 million was still required to complete the subway project.

Contractors’ bids were approved and construction commenced when D.P. Foley General Contractors lifted the first shovelful of dirt out of the canal bed on January 28, 1920. Construction would proceed in phases, sometimes overlapping with work being done on different sections of the proposed route by different contractors simultaneously.

Delays would be experienced, however, partly due to lingering post-war material shortages, but also because of strikes and labor issues prevalent throughout the country during that period.

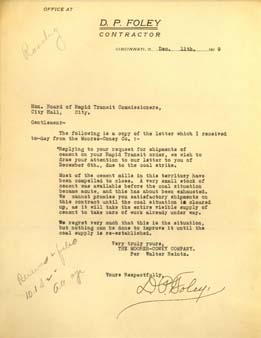

In a letter dated Dec. 11, 1919, contractor D.P. Foley writes to notify the Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners of a delay in receiving a shipment of cement, due to a coal strike which forced several mills to close:

“Hon. Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners,

City Hall, City.

Gentlemen:

The following is a copy of the letter which I received to-day from the Moores-Coney Co.:-

“Replying to your request for shipments of cement on your Rapid Transit order, we wish to draw your attention to our letter to you of December 6th, due to the coal strike.

Most of the cement mills in this territory have been compelled to close. A very small stock of cement was available before the coal situation became acute, and this has about been exhausted. We cannot promise you satisfactory shipments on this contract until the coal situation is cleared up, as it will take the entire visible supply of cement to take care of work already under way.

We regret very much that this is the situation, but nothing can be done to improve it until the coal supply is re-established.

Very truly yours,

The Moores-Coney Company

Per Walter Heintz”

Yours Respectfully,

D.P. Foley

D.P. Foley Letters to Board of Rapid Transit, Dec. 10-11, 1919

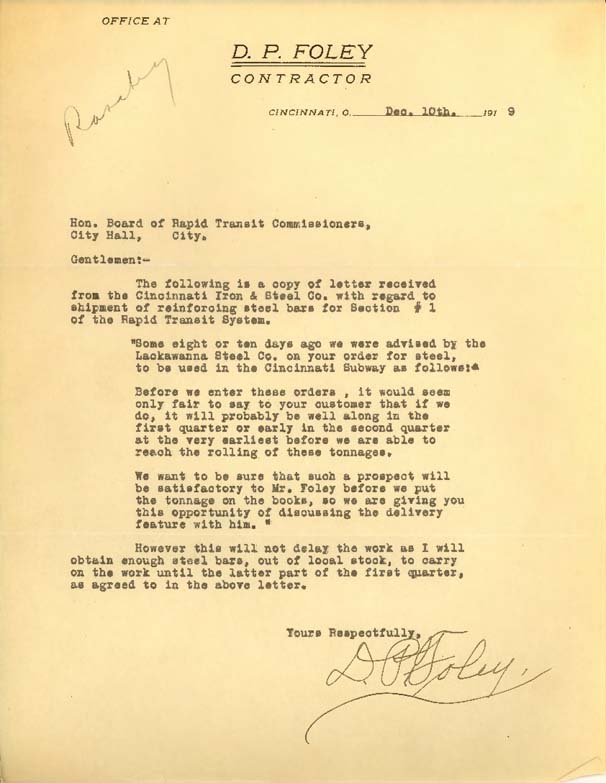

Another letter from Mr. Foley to the Board, dated the previous day, notifies the commission of a delay in delivery of reinforced steel beams. No reason for the delay is given by the company, but a date range of “the first quarter or early in the second quarter at the very earliest” is given as an adjusted delivery date. Mr. Foley goes on to assure the Board that work on the subway will not be impacted by the delay, “as I will obtain enough steel bars, out of local stock, to carry on the work until the latter part of the first quarter…”.

By 1925, the original $6 million bond had run out, with no hope for additional funding. Along with funds, interest and necessity for the subway had diminished. The automobile was all the rage, and the need for an interurban rapid transit system was no longer supported by City Council. Two miles of tunnel lay beneath Central Parkway, from Walnut Street to Hopple Street, along with seven miles of excavation completed for above-ground track. Three underground stations were built at Race Street, Liberty Street, and Brighton’s Corner but left unfinished, as were several above ground stations including the Marshall Street Station, shown below. Today, these tunnels and underground stations, which are still maintained by the city, are all that remain of the Rapid Transit project.

This project is funded by a grant for $60,669 through the Library Services and Technology Act, administered by the State Library of Ohio.