By Janice Schulz

Researchers know that life events tend to leave some amazingly informative paper trails and that sometimes you can find good things in seemingly bad places. For some individuals, a prison sentence was a significant, formative life event, and the paper trails that prison stays provide can tell some interesting stories. The Cincinnati Workhouse, which operated from 1869-1985, tried to take those prison sentences and turn them into more positive experiences for inmates and society through rehabilitation, emphasis on moral ideals, and hard work. As part of our Ohio Network of Local Government Records collection, the Archives and Rare Books library holds jail registers from the Cincinnati Workhouse for the years 1877-1945.

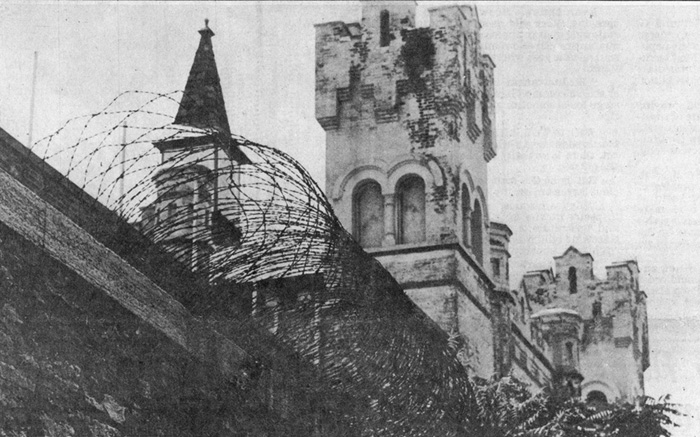

The Cincinnati Workhouse in an idyllic, undated postcard from ARB’s Nelson and Florence Hoffmann Cincinnati Postcard Collection

On March 9, 1866, the Ohio General Assembly passed an act authorizing any Ohio city exceeding 100,000 in population to erect and maintain a workhouse. A workhouse was a new concept in the field of criminal justice, responding to the emerging idea that crime was related to societal and moral issues, and providing not only punishment, but rehabilitation as well. A workhouse aimed to rehabilitate by stressing moral values, providing inmates with something productive to do, and possibly introducing them to a new trade. Additionally, they were seen to be more cost-effective than traditional jails, as inmate labor contributed to the institution’s operations and provided outside income.

On the same day that the General Assembly act was passed, Cincinnati City Council authorized the “Committee on Police, City Prison and Work-house” to purchase a lot adjacent to the House of Refuge for the purpose of building a workhouse. The Cincinnati Workhouse opened on November 17, 1869, with an initial inmate population of 73 males and 10 females. By far the offenses most committed to land people in the Workhouse were drunkenness and disorderly conduct, followed by vagrancy and larceny. The Workhouse was a jail designed for short-term sentences and individuals waiting for court appearances, rather than long-term sentences for serious offenses. It was vice rather than violence that the Workhouse focused on correcting.

At its inception, the main occupation for male inmates was shoemaking. They also performed labor on the grounds and assisted in putting the finishing touches on the facility, which was actually far from move-in condition when they took residence. Women were kept busy cleaning dormitories, doing laundry, working in the kitchen, and performing sewing duties. The workhouse was run almost exclusively through inmate labor, supervised by full-time regular employees, but it was never totally self-sustaining and still required outside funding. Later, inmates were farmed out to work in other city departments and inmate labor became a source of income for the workhouse through contracted jobs.

This 1981 photograph shows that while rehabilitation and moral rectitude were goals of the Workhouse, it was still in essence a prison. From ARB’s Municipal Reference Library collection.

Over the years the Workhouse faced several issues, including overpopulation, inadequate funding, lack of proper facilities, and political struggle. In 1920 it was shut down entirely, opening back up in 1927 under a new management structure, which ushered in a period of stability and success for a couple decades. However, during the 1950s, the Workhouse facilities and its operational ideologies became outdated and as more and more complaints about conditions turned into legal battles, the end of the institution loomed near. By the 1970s there was no question that the Workhouse would be closed, only the timing was unknown. Hamilton County took over ownership of all correctional facilities operated by the City of Cincinnati in 1981, including the Workhouse, while at the same time they were making plans to build a new county justice center. When the new justice center opened in 1985, the Workhouse was no longer used as a correctional facility, and despite its 1980 designation as a national historic place, the building was torn down in 1990. All that is left of the Workhouse facility now resides at the Hamilton County Justice Center – a cell door and the yard bell.

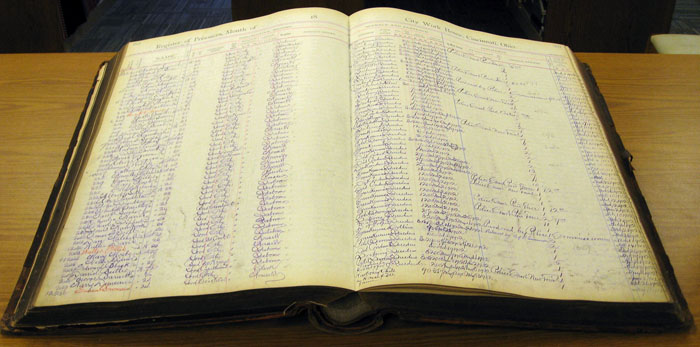

The jail registers in the Archives & Rare Books collection are large bound volumes with one line of information recorded for each inmate.

But something else even more important to the history of not only the Workhouse, but individual and societal study still exists – ARB’s jail registers. The story of the Workhouse itself has been told, but the stories of the people who populated the Workhouse are still there to be discovered. The registers contain information about each inmate, including personal details and specifics about the offense that landed them there. The information recorded changed over the years, but for each inmate, the registers may show name, age, sex, race, distinctive marks, health, residence, nativity, and occupation. Information about their crime and time served includes date of admission, arresting officer, offense, sentencing judge, time, place, and date of offense, date of discharge, final disposition, and additional comments.

The Workhouse jail registers can be viewed at the Archives & Rare Books Library, located on the eighth floor of Blegen library. For further information about ARB and its holdings, please call 513.556.1959, email archives@ucmail.uc.edu, or visit our website at http://www.libraries.uc.edu/libraries/arb/index.html.