By: Kevin Grace

Ninety-eight years ago in 1916, the Irish Republican Brotherhood staged an uprising during Easter Week, the intent being to reclaim Ireland from the British and establish a republic. Though the rebellion failed, as so many others had in the previous two centuries, the rising galvanized the Irish people in a way that would ultimately lead to the country’s independence following a bloody civil war. The Easter Rising and the years following it are complicated ones in sorting out the loyalties and issues, though there has been no shortage of histories and autobiographies and polemics.

Ninety-eight years ago in 1916, the Irish Republican Brotherhood staged an uprising during Easter Week, the intent being to reclaim Ireland from the British and establish a republic. Though the rebellion failed, as so many others had in the previous two centuries, the rising galvanized the Irish people in a way that would ultimately lead to the country’s independence following a bloody civil war. The Easter Rising and the years following it are complicated ones in sorting out the loyalties and issues, though there has been no shortage of histories and autobiographies and polemics.

In the Rare Books Collection, there is another view of the rising: a poetry chapbook by Maeve Cavanagh. Entitled A Voice of Insurgency, Cavanugh’s collection of verse documents the six days of the rebellion from Monday, April 24 through Saturday,April 29 and the men and women who were in the forefront of it as gunshots and cannon fire reverberated around Dublin. Cavanagh was a dedicated supporter of the republican movement, and friends with many of the leaders of the insurgency. Her poems capture the fear and exhilaration of that Easter week.

Cavanagh’s chapbook came to ARB in 2000 as part of the Knott-Radner gift, an important collection of more than 700 items of early 20th century Irish literature. Initially assembled by Eleanor Scott, a scholar of Irish language and literature, the collection later came to be owned by another scholar, Joan Radnor. Radnor, who had been a classmate at Harvard of Professor Emeritus and Celtic scholar Edgar Slotkin, knew of his work at the University of Cincinnati and so her books were offered to UC. Along with former Associate Dean for Collections Jerry Newman, Slotkin arranged for the transfer of Radnor’s collection. The Radnor materials are primarily Irish Gaelic, reflecting the early 20th century literary revival movement in Ireland, and almost immediately after acquiring this gift, Newman and Slotkin were presented with another fine body of books called the Stanley M. Dahlman Collection, which focuses on Welsh language and literature. The two collections have greatly strengthened our holdings on Irish literature and history.

Cavanagh’s chapbook came to ARB in 2000 as part of the Knott-Radner gift, an important collection of more than 700 items of early 20th century Irish literature. Initially assembled by Eleanor Scott, a scholar of Irish language and literature, the collection later came to be owned by another scholar, Joan Radnor. Radnor, who had been a classmate at Harvard of Professor Emeritus and Celtic scholar Edgar Slotkin, knew of his work at the University of Cincinnati and so her books were offered to UC. Along with former Associate Dean for Collections Jerry Newman, Slotkin arranged for the transfer of Radnor’s collection. The Radnor materials are primarily Irish Gaelic, reflecting the early 20th century literary revival movement in Ireland, and almost immediately after acquiring this gift, Newman and Slotkin were presented with another fine body of books called the Stanley M. Dahlman Collection, which focuses on Welsh language and literature. The two collections have greatly strengthened our holdings on Irish literature and history.

Many of the Knott-Radnor volumes are printed on poor paper and are in fragile condition, particularly the poetry. The Cavanagh volume, which is currently undergoing treatment in the joint UCL/Cincinnati Public Library Preservation Lab, is in very good condition with the exception of the paper cover.

Many of the Knott-Radnor volumes are printed on poor paper and are in fragile condition, particularly the poetry. The Cavanagh volume, which is currently undergoing treatment in the joint UCL/Cincinnati Public Library Preservation Lab, is in very good condition with the exception of the paper cover.

The poems in A Voice of Insurgency are by turns fiery, tender, defiant, and sad. Cavanagh composed these poems in the weeks and months after the rising was put down by British troops, and its leaders executed. At its end, more than 400 people were dead and 2500 were wounded, most of them civilians. In fact, one of the casualties was Cavanagh’s own brother, Ernest, a prominent political cartoonist. Though Ernest Cavanagh also supported the republican movement, he was not involved in the actual fighting. Standing on the steps of Liberty Hall, the Dublin headquarters of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, Cavanagh was shot dead by a British sniper on April 25. His sister eulogized him in a later poem:

To every noble cause your heart

Went forth unerring, true,

Maybe you played a greater part,

And braver than you knew.

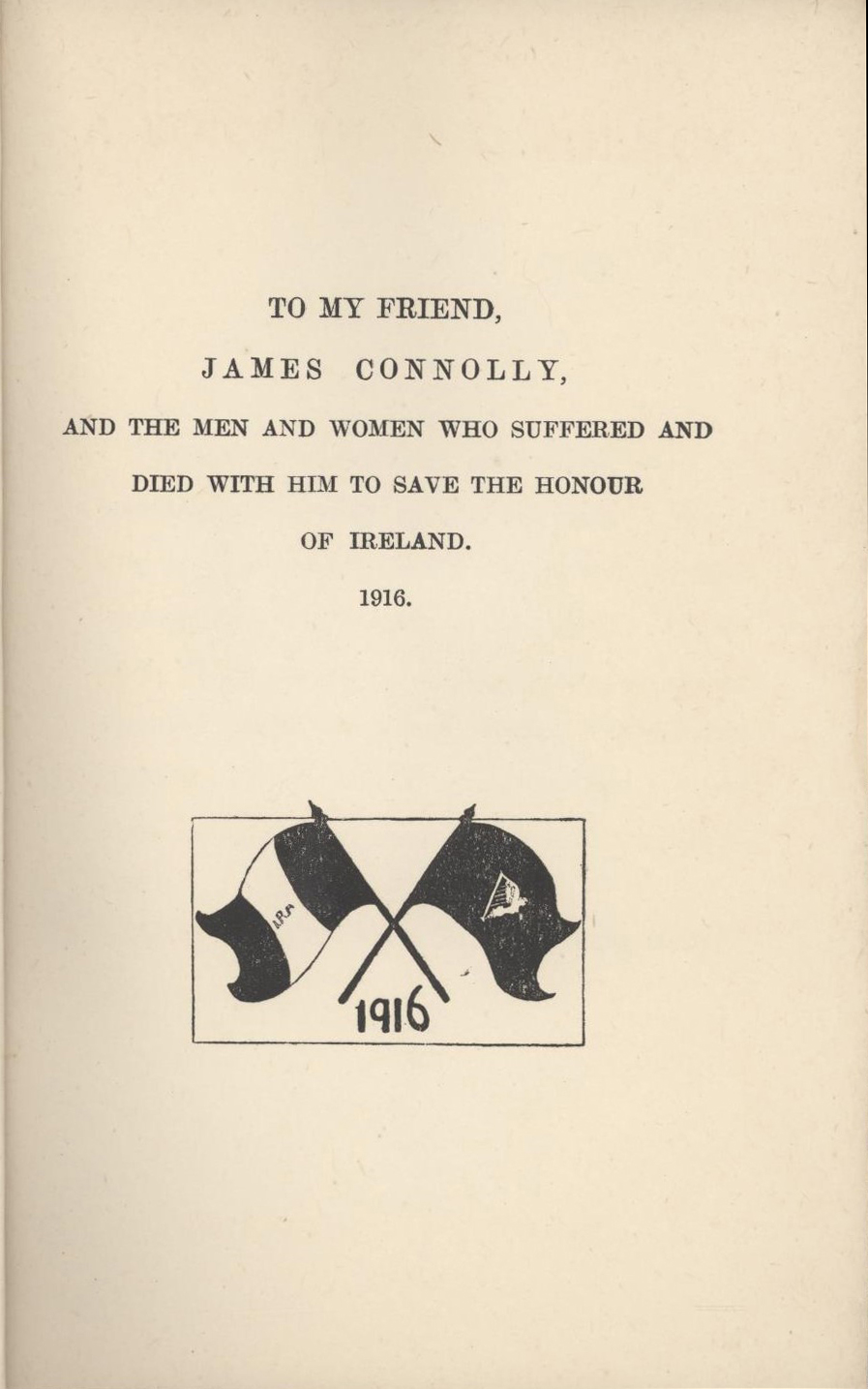

Maeve Cavanagh’s book was published on Christmas Eve, 1916 and sold out in less than a month’s time. She dedicated it to her friend, Irish patriot James  Connolly, who was one of the 90 people sentenced to death by British courts martial. Connolly, a labor leader and socialist, was one of the signatories to the famous Proclamation of the Republic that declared Ireland’s fight for freedom. He had been badly wounded during the fighting, suffering a shattered ankle in addition to other injuries. Connolly was transported to Kilmainham Gaol, carried to the courtyard on a stretcher, tied to a chair because he could not stand, and executed by firing squad.

Connolly, who was one of the 90 people sentenced to death by British courts martial. Connolly, a labor leader and socialist, was one of the signatories to the famous Proclamation of the Republic that declared Ireland’s fight for freedom. He had been badly wounded during the fighting, suffering a shattered ankle in addition to other injuries. Connolly was transported to Kilmainham Gaol, carried to the courtyard on a stretcher, tied to a chair because he could not stand, and executed by firing squad.

Cavanagh continued to write poetry in the years following the Easter Rising and established a fair reputation for her work. In 1922, as the Irish Civil War was fully underway, she married Cathal MacDowell, an Irish Volunteer. The bulk of her manuscripts are now housed in the National Library of Ireland.