By: Nathan Hood

Dr. Cecil Striker, after the International Diabetes Clinic (Indiana University). This photo serves as a link to the finding aid for the Winkler Center’s collection on Dr. Cecil Striker.

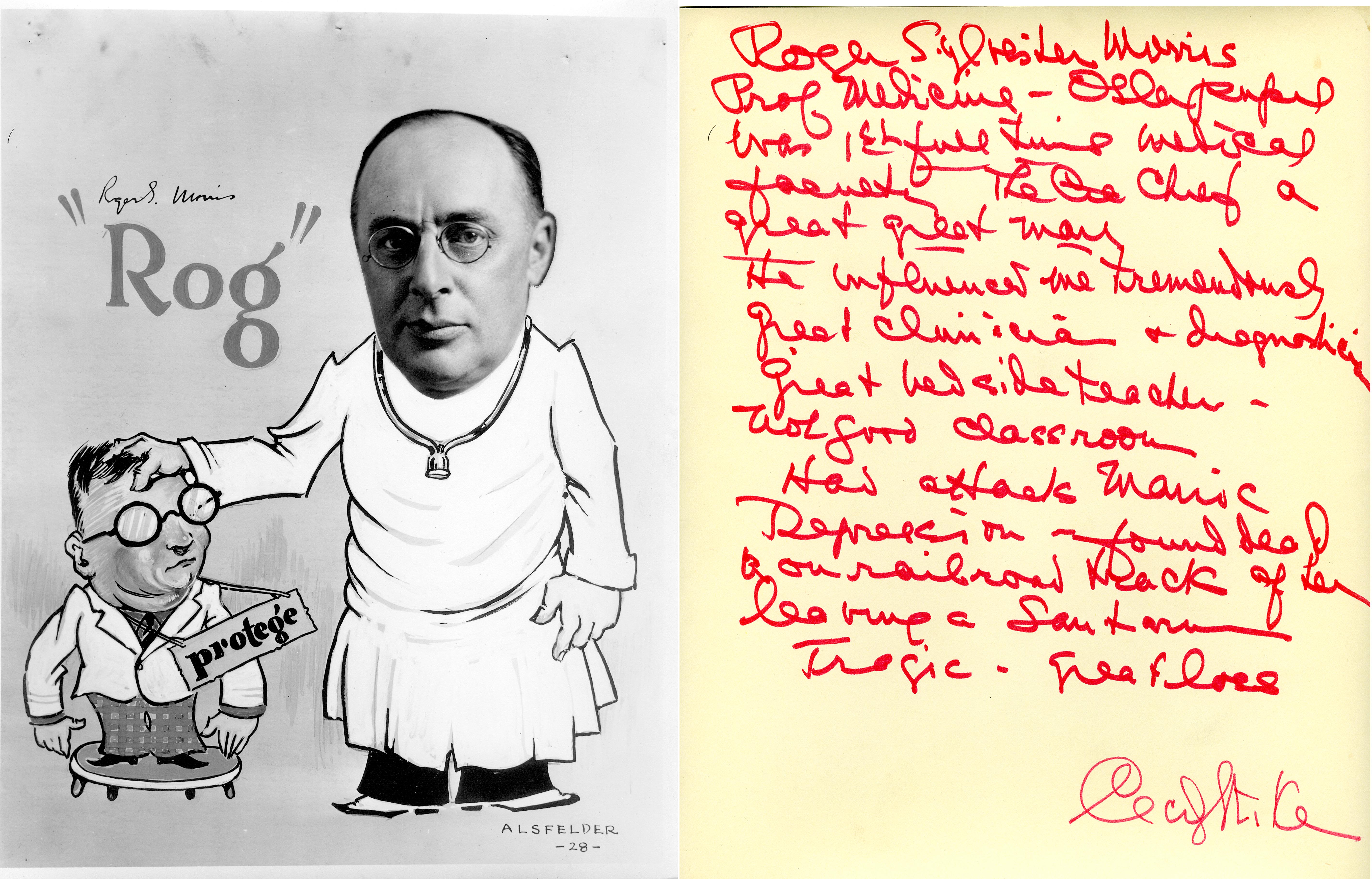

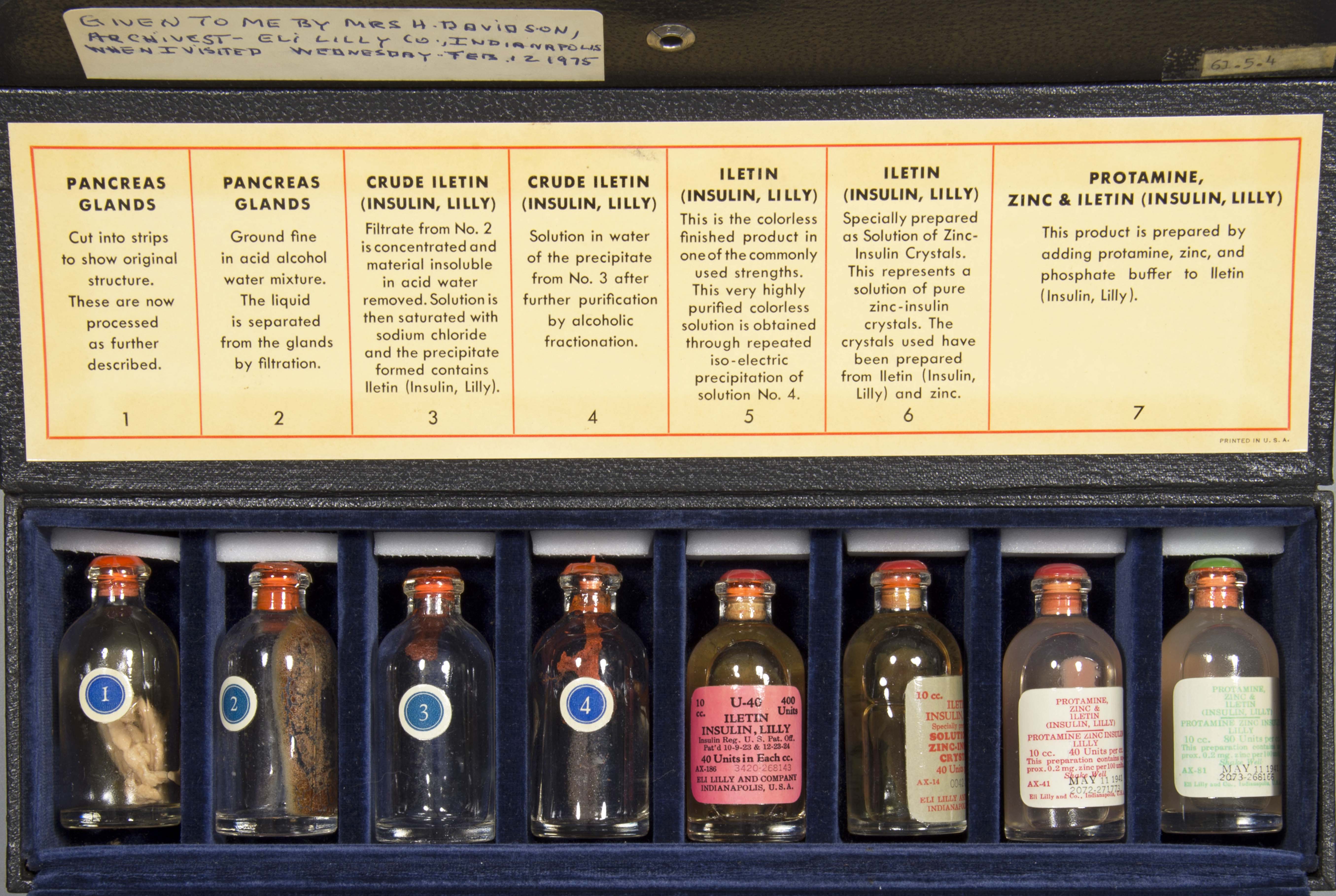

Dr. Cecil Striker’s intense professional passion for Diabetes research began during his one-year residency, which had itself began in 1923 at the recently finished Cincinnati General Hospital. The first full-time Professor of Endocrinology at the Medical College, Dr. Roger Sylvester Morris, had assigned Striker the task of testing a fairly new medication received from the Eli Lilly Company (Indianapolis) – a “drug” named insulin! Insulin and its medical application had only just been discovered about a year earlier.

A cartoon of Dr. Roger Sylvester Morris. This image serves as a link to the blog, “Magnifying the Past: The ‘Alsfelder’ Faculty Caricatures.” This cartoon and others like it were originally obtained by Dr. Striker.

“Diabetes was the absorbing professional field for the rest of Cecil’s life; he became nationally and internationally known as a consultant to physicians caring for patients with this disease. And, it seems almost natural that, with his talent for organizing things, Cecil should have been the motivating force for the founding of the American Diabetes Association….” (from page 1 of “Memorial Resolution for Cecil Striker, M.D.”)

Truly, despite the game changing scientific discovery of insulin and it’s significant medicinal application, Dr. Striker is correct when he explains that it was not a breakthrough of science, but rather the dedication of several medical professions which brought about the founding of the ADA – Dr. Striker most certainly among them!

In fact, not only was Dr. Striker an essential contributor to the formation of the ADA but he also took the opportunity to record its history in several ways. One of the most historically informative being a lengthy book he and Associate Professor Paul F. Erwin intended to have published in the early 1970’s titled, The American Diabetes Association: 1940 – 1970. Indeed, it is fortunate that Dr. Striker was perhaps just as enthusiastic about recovering and preserving history as he was about Diabetes research and treatment. In addition to this manuscript and among his other eclectic collections preserved at the Winkler Center, there exists ten of his “Book Shelf Scrapbooks.” These contain close to thirty years-worth (approximately 1945-1975) of often brief, yet pertinent and informative documents, photographs, articles, etcetera. Combined together with other relevant ADA materials Dr. Striker filed away, the Cecil Striker collection provides a fair amount of insight into the happenings of the ADA, especially for anyone determined enough to sift through the minutiae.

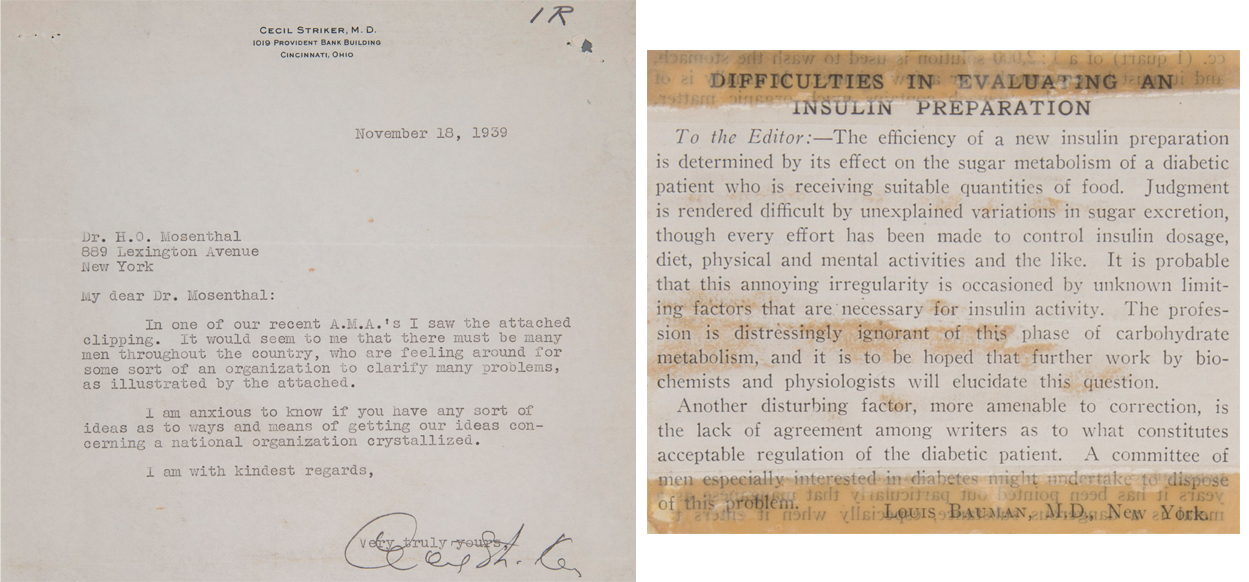

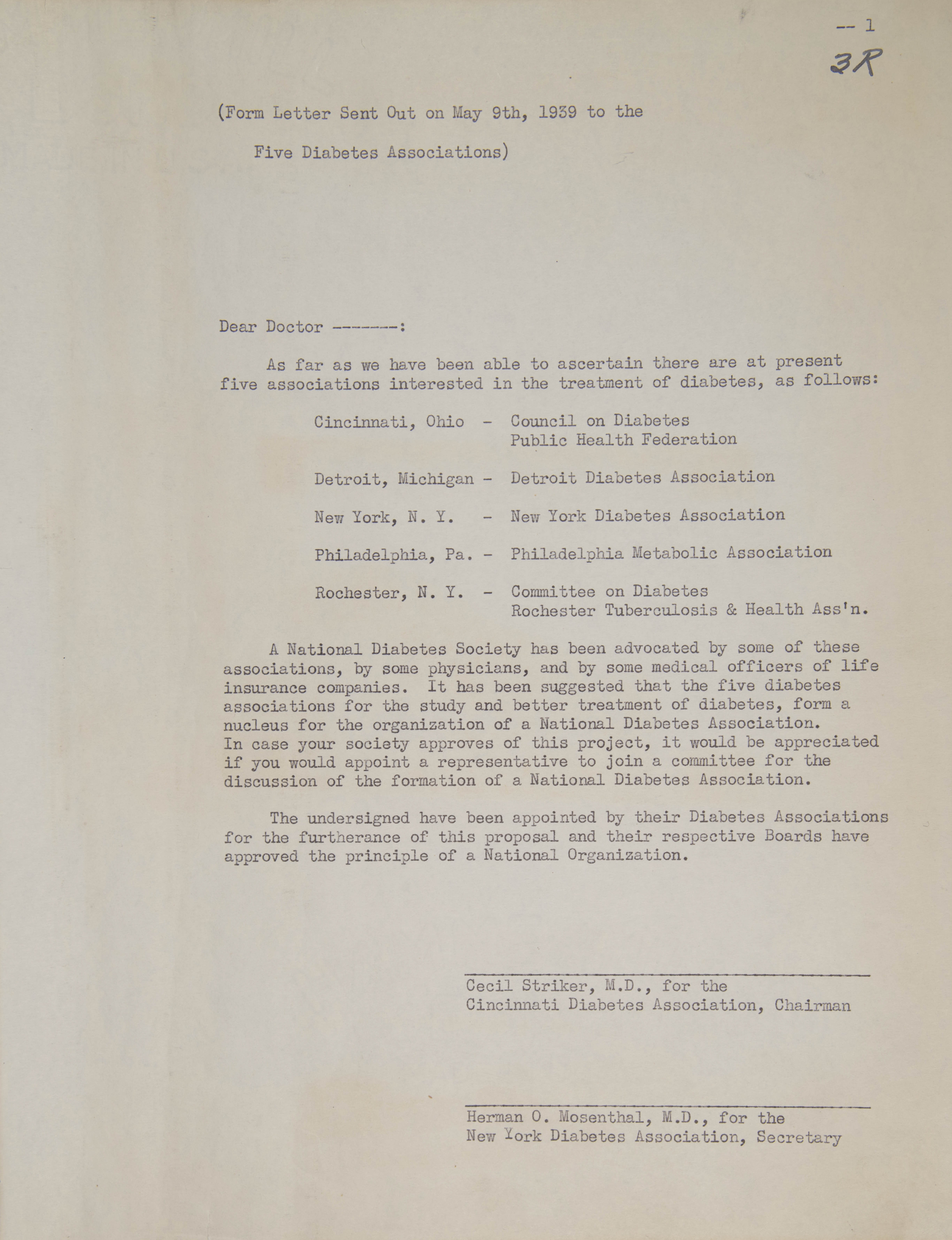

According to Dr. Striker, discussion of the kind of national organization that would eventually become the ADA began in 1937, New Orleans, at an American College of Physicians meeting. After about a year, several of those who had originally participated resumed their preliminary discussion. Perhaps most notably among them were Drs. Striker and Herman O. Mosenthal. It was soon realized that the creation of a national diabetes association might be more easily effectuated with the cooperation and organization of all the “local diabetes groups.”

In 1939 there appeared to be five smaller, similar, yet fairly independent organizations “interested in the treatment of diabetes”: The Council on Diabetes Public Health Federation; Detroit Diabetes Association; New York Diabetes Association; Philadelphia Metabolic Association; and The Committee on Diabetes Rochester Tuberculosis & Health Association. All had been recently founded in in the 1930’s.

Around that time, Dr. Striker was a member of the Cincinnati Diabetes Association, which was likely connected to, or in some way affiliated with the Council on Diabetes Public Health Federation. Regardless, Dr. Striker as well as Dr. Mosenthal – an affiliate of the New York Diabetes Association – collaborated together in order to contact the other three diabetes associations:

“…formally inviting the physicians active in each to become members of the new national group, and specifically, to send delegates to aid in the actual founding of the new [national] association.” (From page 3 of The American Diabetes Association: 1940-1970)

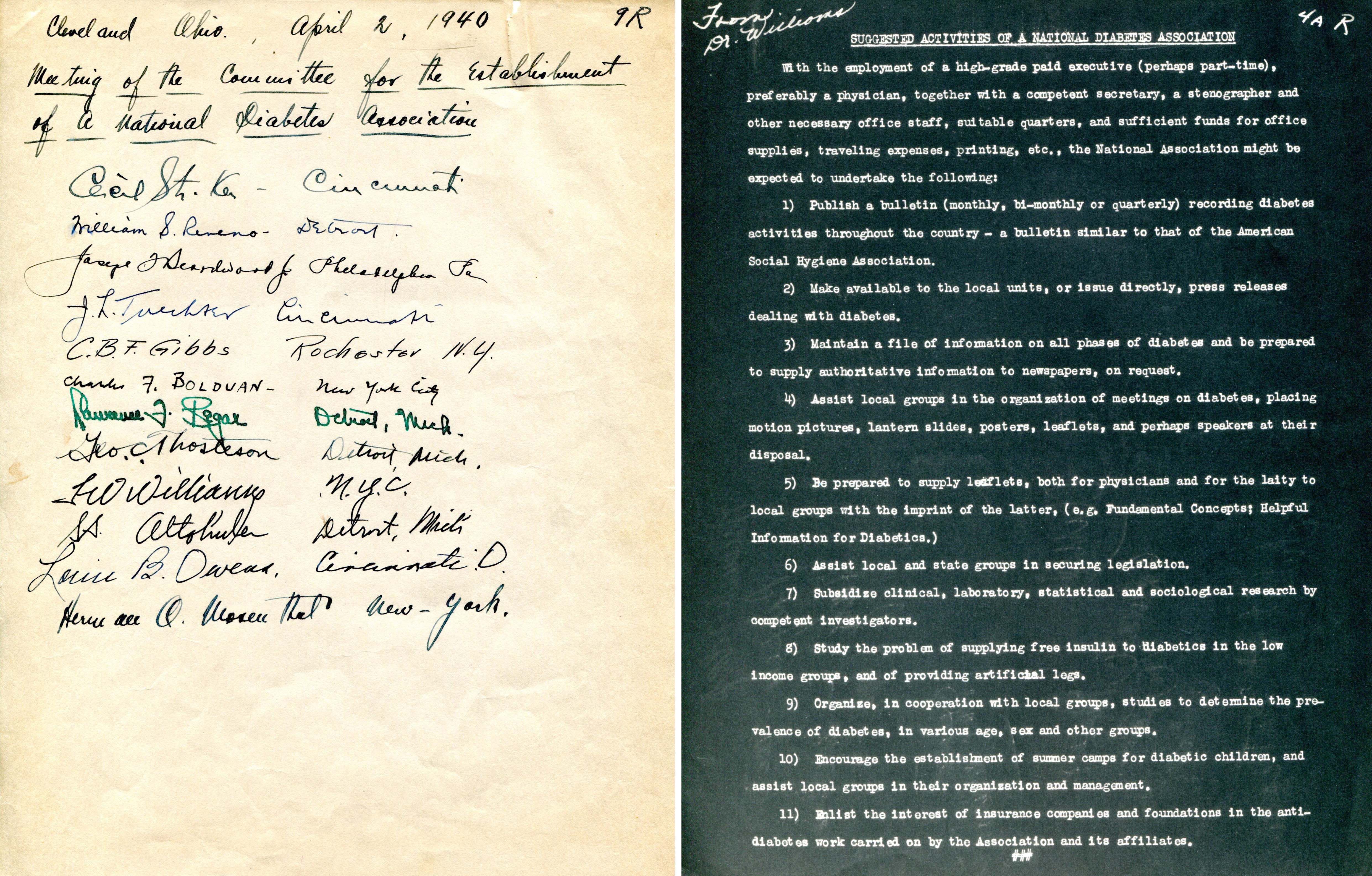

A total of twelve representatives from the five associations met for the first time on April 2, 1940, at the Hotel Stafler in Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Striker opened the meeting and expressed the intention “that the new National or American society, though started by the various local organizations, ultimately would be independent of them.” All but one of the delegates were more or less in favor of a national organization of this sort. The delegates requested that Dr. Striker appoint the members of “three committees consisting of three members each”: 1). Purposes and Scope, 2). Constitution and By-laws, and 3). Finances. The next meeting transpired on June 12, 1940.

Attendence of the ‘first meeting’ (left); Dr. Charles F. Bolduan’s (Assistant Health Commissioner of New York City) suggestions presented to the delegates at the first meeting on April 2, 1940 (right). According to Dr. Striker, these suggestions would prove to be of great benefit to the ADA.

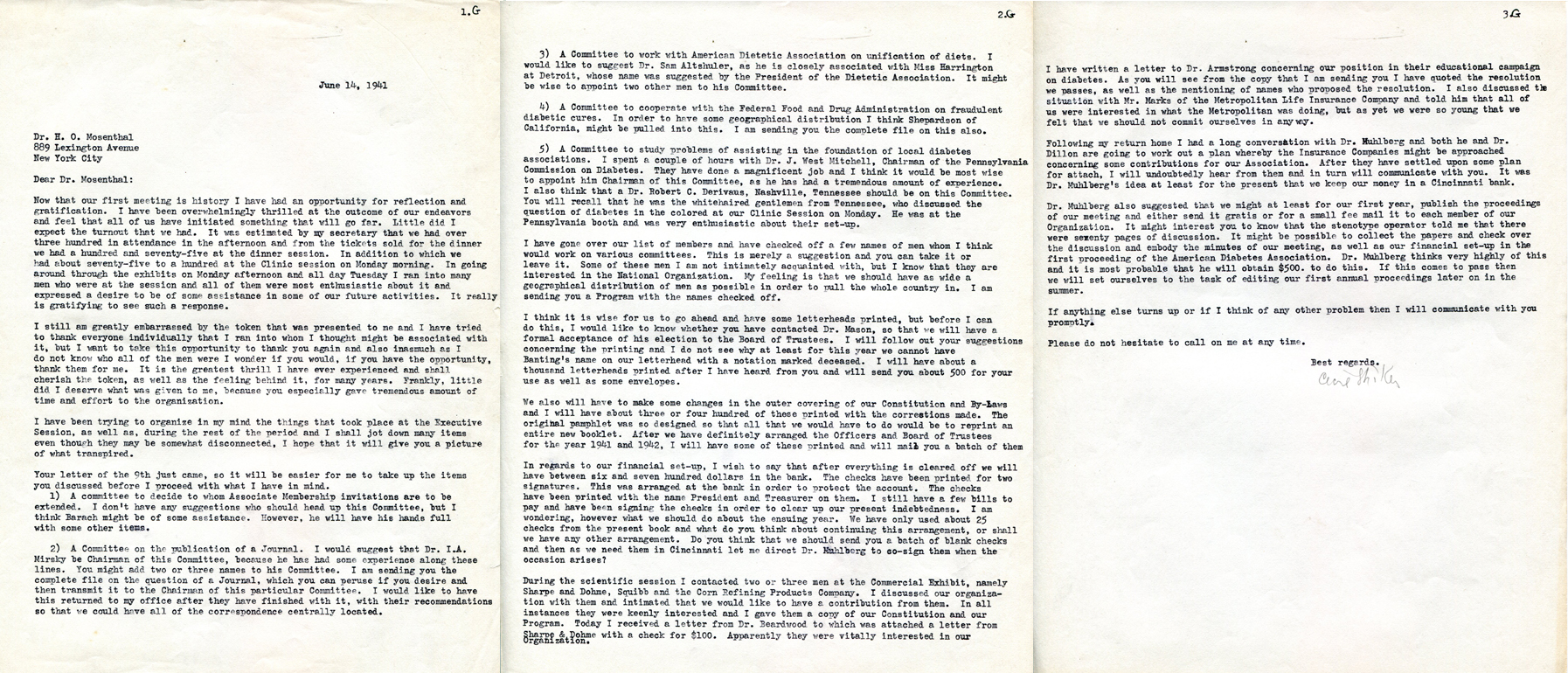

This second meeting took place at Schrafft’s Restaurant (46th Street and Fifth Avenue) in New York and “became the charter meeting of the ADA.” A constitution and by-laws were passed pending legal approval and Dr. Mosenthal nominated Dr. Striker for the position of President; he was immediately and unanimously accepted as the first President of the ADA. The first annual meeting of the ADA was held in Cleveland on June 1, 1941. After his term as president, he served for many years as the Association’s secretary.

Correspondence addressed to Dr. H. O. Mosenthal shortly after the first meeting of the ADA and during Dr. Striker’s term as president.

Of course, the ADA was not Dr. Cecil Striker’s sole preoccupation. However, it may be said that Dr. Striker’s personal collection of ADA materials, in the very least being an inherent part of his scrapbooks, seemingly represent a convergence of his intense interests – at least those of diabetes research and history. Thoughtful, organized, but in my humble opinion, also playful in a way –Indeed, there is a sense of the man in this portion of his collection. Many thanks to him for his foresight and contribution not only to medicine but also to historical record.

“The author [Dr. Striker] is confident that, had it not been for the wise counseling of … [many] men and their work and inexhaustible enthusiasm, the American Diabetes Association might not have been established.” (From page 9 of The American Diabetes Association: 1940-1970)

No doubt Dr. Striker himself, is among those men. Fortunately, his vision for the ADA as well as the organization itself has continued to prosper in his absence. Dr. Striker’s commentary in the 70’s still holds true, and remains entirely relevant to this day:

“The American Diabetes Association from its founding has been an important factor in the scientific life and growth of the American people. Paralleling and in part generating the emerging concern of our nation for better health and welfare since the thirties, the American Diabetes Association has become a vital American institution.” (From the “Foreword” of The American Diabetes Association: 1940 – 1970.)

Today, the American Diabetes Association has thrived and developed into “a network of more than one million volunteers, a membership of more than 441,000 people with diabetes, their families and caregivers, a professional society of nearly 16,500 health care professionals, as well as more than 800 staff members” and numerous corporate sponsors. Their mission: “to prevent and cure diabetes and to improve the lives of all people affected by diabetes.”

With so many involved, the ADA now “fund[s] research to prevent, cure and manage diabetes … deliver[s] services to hundreds of communities … provide[s] objective and credible information … [and] give[s] voice to those denied their rights because of diabetes.”

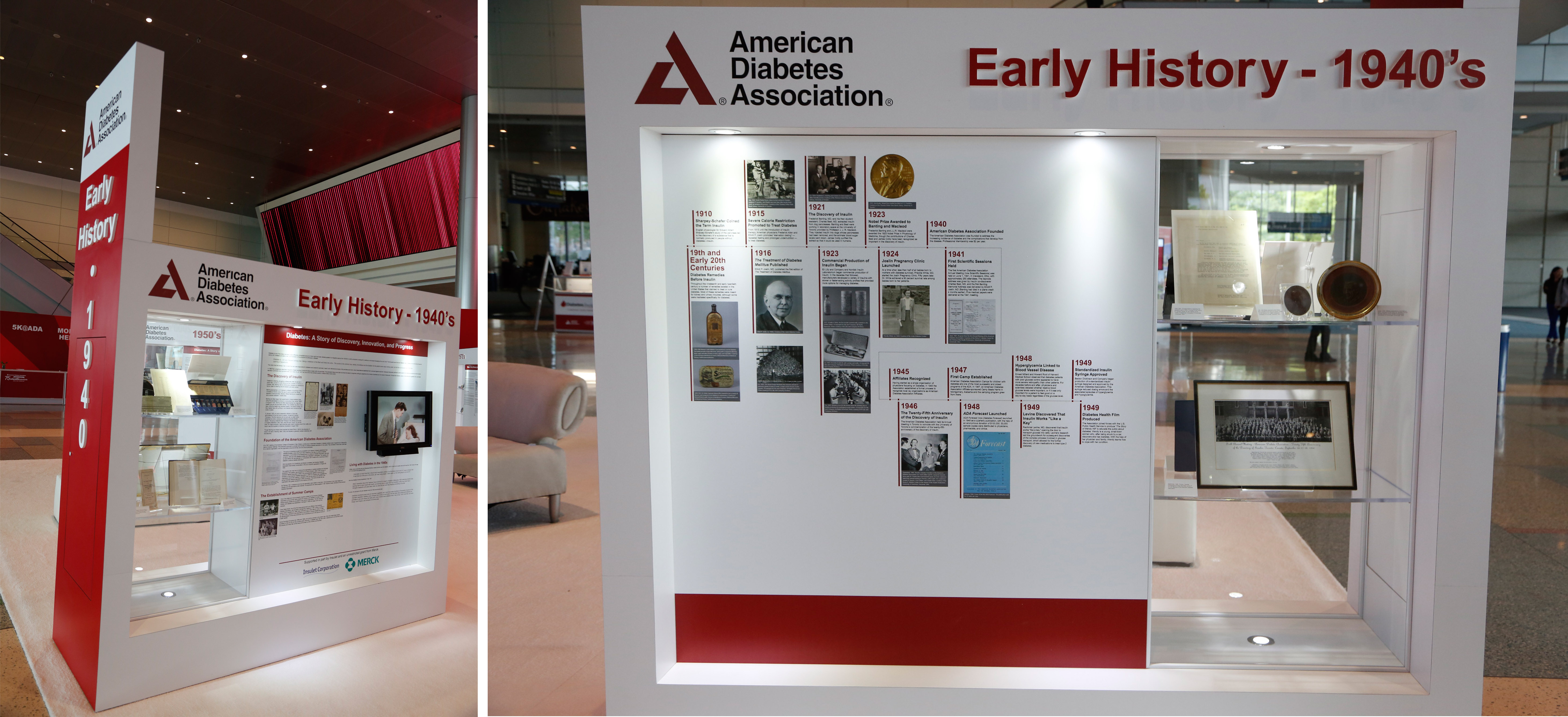

Earlier in April and May of this year, the ADA requested and were loaned various materials from The Henry R. Winkler Center for the History of the Health Professions’ Cecil Striker Collection. Books, medals, correspondence, etcetera – these artifacts honoring and celebrating the contributions of the ADA’s founders were displayed at the organization’s 75th Scientific Sessions held on June 5-9 in Boston, Massachusetts.

The ADA’s display at their 75th Scientific Sessions, Ariel view. Dr. Cecil Striker’s Materials mostly contained within the “Early History — 1940’s” case.

This photo serves as a link to the ADA’s “75th Anniversary Timeline.”

Photo by © ADA/Todd Buchanan (2015) contact info: todd@medmeetingimages.com

The “Early History — 1940’s” case at the ADA’s 75th Scientific Sessions.

This image serves as a link to the official American Diabetes Association (ADA) website.

Photos by © ADA/Todd Buchanan (2015), contact info: todd@medmeetingimages.com

A special thanks to The University of Cincinnati Preservation Lab for their efforts in preparing several of Dr. Striker’s documents and artifacts for display.

Display box of 8 sealed bottles and description of Iletin production, produced by Eli Lilly Co., Indianapolis, IN, 1941.

Utilized in the ADA 75th Anniversary Exhibit,

June 5-9 2015, Boston, Massachusetts

Photo by: Jessica Ebert, The Preservation Lab

For more information, to view a collection, or for a tour of The Winkler Center, please call 558-5120 or email chhp@uc.edu to schedule an appointment.