By Eira Tansey, Digital Archivist/Records Manager

When archivists first make contact with a large group of records, they often perform some form of appraisal. You might think of appraisal as being the calling card of the much-loved PBS television show Antiques Roadshow, in which average people realize that Great Aunt Milly’s painting is a valued masterpiece – or a total dud.

Unlike appraisers, when archivists appraise something they generally aren’t assigning a monetary value, but seeking to articulate the value of the records and the information they contain. The Society of American Archivists defines (http://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/a/appraisal#.V2hA1jXERmM) appraisal as:

- ~ 1. The process of identifying materials offered to an archives that have sufficient value to be accessioned. – 2. The process of determining the length of time records should be retained, based on legal requirements and on their current and potential usefulness. – 3. The process of determining the market value of an item; monetary appraisal.

The vast majority of archivists engage in definitions 1 and/or 2. Few archivists perform monetary appraisal, indeed it is often a conflict of interest for an archivist to perform monetary appraisals, especially if the material under consideration is within the collecting area of the repository s/he works at. Appraisal is a perennial “hot topic” within the archival profession, since appraisal typically results in a final decision on what to accept and accession (i.e. take physical and legal custody of) into the archive.

Appraising electronic records has many similarities and differences from appraising paper records. Like appraisal of paper records, archivists must get an idea whether there are any potential preservation issues with the content. For example, archivists working with paper records are attuned to look for signs or smells related to paper damage – a water-stained box may later reveal damaged photographs, or pest droppings may be associated with chewed-on pieces of paper. A strong presence of a funky vinegar smell (“vinegar syndrome”) may suggest highly-flammable film or negatives.

But what about electronic records? First, most digital archivists will run a virus check as one of the first steps when dealing with a new group of electronic records. This is similar to how many archives have an “isolation room” when they bring in records they have reason to believe may be infested with pests. Second, it is critical to know if there are any funky file formats lurking in the group of records. Unusual file formats can incur a lot of staff time and resources in finding ways to read the content of the file.

After running a virus check, I like to get a sense of the types of files I’m dealing with, in case there are files that are of such high-value I need to prepare for file format migration. I do this by generating a manifest of all the files, directories, file formats, modification dates, and file sizes. My current method for doing this involves the beginner-friendly command-line lessons shared by Bert Lyons at the Midwest Archives Conference a few years back. An update version of these instructions can be found here (https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B-FBppbZcJ2EYUVaeXhLdlNtbE0&usp=sharing#list)

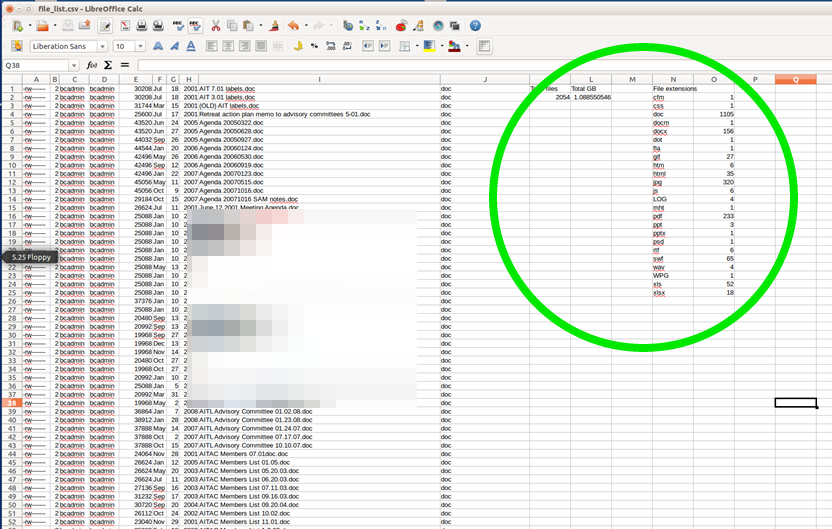

Here is a screenshot of what this manifest looks like:

Now, even though I only have a very basic idea of the file contents from the file names, I have a better sense of my technical needs for this particular collection. Luckily the vast majority of the files are mainstream Microsoft Office file formats. While they aren’t necessarily as “open” as other file formats, we are not migrating common Microsoft Office file formats at this point in time due to resource limitations. I also have a sense of the total size of the collection, and all the dates. I will eventually include this file manifest with the other accession documentation, since I may remove some files between the initial appraisal and the final accession.

Appraisal involves much more than just assessing the physical state of the records. It also involves making sense of the intellectual arrangement and value of the records. Future posts will delve more deeply into these topics.

The Archives and Rare Books Library is located on the 8th floor of Blegen Library. We are open Monday through Friday, 8:00 am-5:00 pm. You can also call us at 513.556.1959, email us at archives@ucmail.uc.edu, visit us on the web at. http://www.libraries.uc.edu/arb.html, or have a look at our Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/ArchivesRareBooksLibraryUniversityOfCincinnati.