By: Sydney Vollmer

On August 17, 1866, Sarah Frances “Fanny” Frost was born in Caldbeck, England to John and Sarah Frost. As Julia Marlowe, she died at age 84 in New York City’s Plaza Hotel. Between those two events, she discovered passion, love (multiple times), and fame.

On August 17, 1866, Sarah Frances “Fanny” Frost was born in Caldbeck, England to John and Sarah Frost. As Julia Marlowe, she died at age 84 in New York City’s Plaza Hotel. Between those two events, she discovered passion, love (multiple times), and fame.

The future Shakespearean actress was born into a relatively normal family. She had four siblings, three sisters and a brother and her parents owned a general store while also working in the trades of needlework and boot making. Her father sometimes got drunk and her mother always got frustrated with him. At the age of 5, though, all of that “normalcy” changed for Marlowe. It was the year that her father whisked the family away to America. Plenty of people were immigrating to America during the 1870s, but Marlowe’s father did so to stay out of trouble. During an impromptu horse race between her father—where he was most likely drunk— and one of their neighbors, Mr. Frost allegedly took out his competitor’s eye with his whip. Knowing that he would surely face prosecution if he stayed, he immediately took his wife and children to America. Once arrived, they first settled in Kansas, but soon moved to Portsmouth, Ohio with the new surname “Brough,” which was the maiden name of Julia’s mother. Later on, the family would find out that the competitor had been playing a cruel joke and there had not been any reason to leave so urgently.

After living in Portsmouth for a short time, the family yet again relocated downriver to Cincinnati and this is where Marlowe spent the majority of her adolescence before leaving for New York. In Cincinnati, her parents sought a divorce. Shortly thereafter, Marlowe’s mother remarried. Her new husband went by the name of “Hess.” He was not a kind man, and he resented his new wife’s children. Not wanting to go against her husband, the two were often harsh with the youngsters, demanding they learn a trade so they could help provide for the family and fill any idle time they may have had. To aid them in this, like many parents still today, they gave the children weekly chores. It was the allowance from said chores that gave Marlowe the ability to buy her first book of Shakespeare.

The purchase was made some time when Julia was ten years old. A travelling book salesman came to the family’s door, a common method for selling books in the late nineteenth century. Marlowe’s mother was taken by the Bible—as she often was—but Marlowe fell in love with a Shakespeare volume at first sight. Being young, she did not have the finances to pay for the book directly, but she bargained with her mother and they eventually came to the agreement that she could have the book, but she would sacrifice her allowance until it was paid off. Delighted with the arrangement, she took the deal and read the book in any moment of spare time she was given.

The purchase was made some time when Julia was ten years old. A travelling book salesman came to the family’s door, a common method for selling books in the late nineteenth century. Marlowe’s mother was taken by the Bible—as she often was—but Marlowe fell in love with a Shakespeare volume at first sight. Being young, she did not have the finances to pay for the book directly, but she bargained with her mother and they eventually came to the agreement that she could have the book, but she would sacrifice her allowance until it was paid off. Delighted with the arrangement, she took the deal and read the book in any moment of spare time she was given.

It wasn’t too long before Marlowe was able to take her love of reading plays and transform it into performing them herself. She was 12 when she saw an ad in the newspaper looking for children to perform in Pinafore. Alone, she went to the shop listed on the advertisement. The shopkeeper, amazed at the child’s boldness, sent her home to receive permission from her mother. After meeting with those in charge, her mother agreed and off Marlowe went with the company in the role of a common sailor, under the care of actress Ada Dow, and director Colonel Robert E. J. Miles. During the run of the play, Marlowe decided that acting was her dream. When she came home and was badgered about what she was going to be when she grew up, knowing acting wasn’t something her overly-religious mother supported, she tried dressmaking, factory work, and being a telegraph operator. None of those careers would do. Marlowe simply would have nothing less than the stage.

During her teens, Julia Marlowe was reunited with Ada Dow, who trained her and often took her to the theatre. “Aunt Ada,” as Marlowe called her, was the sister-in-law of Colonel Miles, who had become the manager of the Cincinnati Grand Opera House. Through that connection, Marlowe was awarded the opportunity to pursue smaller roles with the company, including her first roles in Shakespeare as Balthazar in Romeo and Juliet, and Maria in Twelfth Night. At the end of the season, Marlowe was placed under Ada’s care, who took her to New York when she turned 18.

During her teens, Julia Marlowe was reunited with Ada Dow, who trained her and often took her to the theatre. “Aunt Ada,” as Marlowe called her, was the sister-in-law of Colonel Miles, who had become the manager of the Cincinnati Grand Opera House. Through that connection, Marlowe was awarded the opportunity to pursue smaller roles with the company, including her first roles in Shakespeare as Balthazar in Romeo and Juliet, and Maria in Twelfth Night. At the end of the season, Marlowe was placed under Ada’s care, who took her to New York when she turned 18.

Each day they rehearsed and rehearsed, going over characters, annunciation, and lines. Again, utilizing the connections with Miles, Marlowe was given a chance to perform with the Bijou Opera House for two weeks in Ingomar as Parthenia. Feeling the name “Fanny Brough” no longer suited her, she changed to “Julia Marlowe”—Julia after the heroine in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Marlowe after Christopher Marlowe. Being her first time performing in New York, it would be fair to assume that the critics tore her performance apart. However, that was hardly the case. They noticed her pitfalls, but they mostly noticed her potential. Edward A. Dithmar of the Times wrote of the performance:

Miss Marlowe is not a spectacular Parthenia. She did not conquer by a glance or a gesture. She is not statuesque. She is comely and of good figure, but not beautiful. Her eyes are the most attractive feature of her face, which is uncommonly mobile and intelligent. She depicted the simplicity and love of the Greek maiden in a sensible, straightforward manner that convinced the minds and touched the hearts of everybody present who had a mind and a heart. Her work was marked by none of the failings of the novice. Her touch was always sure, and she impressed the critical observer with a sense of the ability to calculate beforehand the actual effect of every look and gesture. This is a faculty that three-fifths of the actors now on the stage do not possess. Her conception of the character was clear and reasonable; her execution of it, womanly and, above all, intelligent. She had no “great moments.” She made no conspicuous points.

But her grasp of the character never relaxed, and she preserved the illusion under the most distressing surroundings. The episode of the song of love was treated daintly and without exaggeration. The defiance of Ingomar was true and affecting, and not stagy. She expressed the anger of the girl very vividly, and without resort to any hackneyed artifice. She was equally successful with every other phase of the role. She did not carry her expression of love to the limits of great, absorbing passion; but Parthenia is not a woman of strong passions.

In depicting the ingenuousness of the girl, she was not too coy. When she wept, the tears seemed to be real; and her smiles seemed to be the reflection of a sunny temperament. Her voice is strong and pleasing; and if she has a singing voice, it ought to be pure contralto. The tones are never mannish; and, best of all, she speaks the English language very well.

Reviews of a similar note were published in the Nym Crinkle and in the Herald.

The performance led to great things for Marlowe. Col. Miles became her manager and introduced her to H. E. Bristol, an owner of a small restaurant. So impressed was he by her performance, he gave her $5000 when Henry E. Abbey offered her a week to perform at the Star Theatre. Having the freedom to choose what she would perform, she selected Romeo and Juliet, Twelfth Night, and Ingomar. In creating her own company, she chose renowned actor Joseph Haworth as her leading man. Though skeptical about performing with someone so new, all it took was one quick reading of the famous balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet to seal the deal.

The performance was received well enough. Despite audiences loving her performance, the general consensus was that Marlowe was too young and inexperienced to play leads in Shakespeare. She was told multiple times that she would not make any money and her time would be wasted pursuing Shakespeare. In attempts to give her more experience, she was offered a position at a stock theatre company. However, each time she was met with negativity she refused, stating that she could not possibly work in an environment where she did not have creative control. After all, it wasn’t about the money or job security for Miss Marlowe. All she wanted was to perform, and perform she did.

The performance was received well enough. Despite audiences loving her performance, the general consensus was that Marlowe was too young and inexperienced to play leads in Shakespeare. She was told multiple times that she would not make any money and her time would be wasted pursuing Shakespeare. In attempts to give her more experience, she was offered a position at a stock theatre company. However, each time she was met with negativity she refused, stating that she could not possibly work in an environment where she did not have creative control. After all, it wasn’t about the money or job security for Miss Marlowe. All she wanted was to perform, and perform she did.

By the year 1888, Marlowe’s career truly took off. It was also that year when she met her future husband, Robert Taber. Established with the Boston Museum, Taber was already a well-known American actor when he began performing with Marlowe. Together, they put on a number of Shakespearian and other classical plays. The two approached new characters from opposite directions. Marlowe, for her part, would come to a new character meekly. In this way, she would let herself get to know the characters better and eventually build them to their true potential. Taber did the opposite, coming at a character full blast and settling it down as time went on. The creative differences offered a unique dynamic. It was one that must have worked for a time, as the two were married in 1894.

In between that time, Marlowe took a break from acting due to contracting typhoid fever in 1891. Ironically, the illness turned out to be a blessing. Although she loved her Aunt Ada, she had been under a strict legal arrangement with her. When she became ill, the contract was dissolved. After she returned to work, Marlowe and Taber continued to tour. In the 1895-96 season, Taber and Marlowe set out to perform Henry IV and She Stoops to Conquer. Not having strong roles for women, Henry IV was played by Marlowe out of consideration for her husband. Taber picking shows where he would get to outshine his wife became a pattern.

When Marlowe came under the management of Charles Frohman—one of the men who had originally tried to discourage her from forming her own company—in 1896, now discouraged her from performing with her husband. He did not want to manage her if she continued to co-star, believing she would be more successful on her own. This time, Marlowe took his advice. Taber, insulted by the news, moved to England where he thought he might have a better chance at respect as a performer. Unfortunately, the rift was too much for the relationship, and the marriage ended in divorce in 1900.

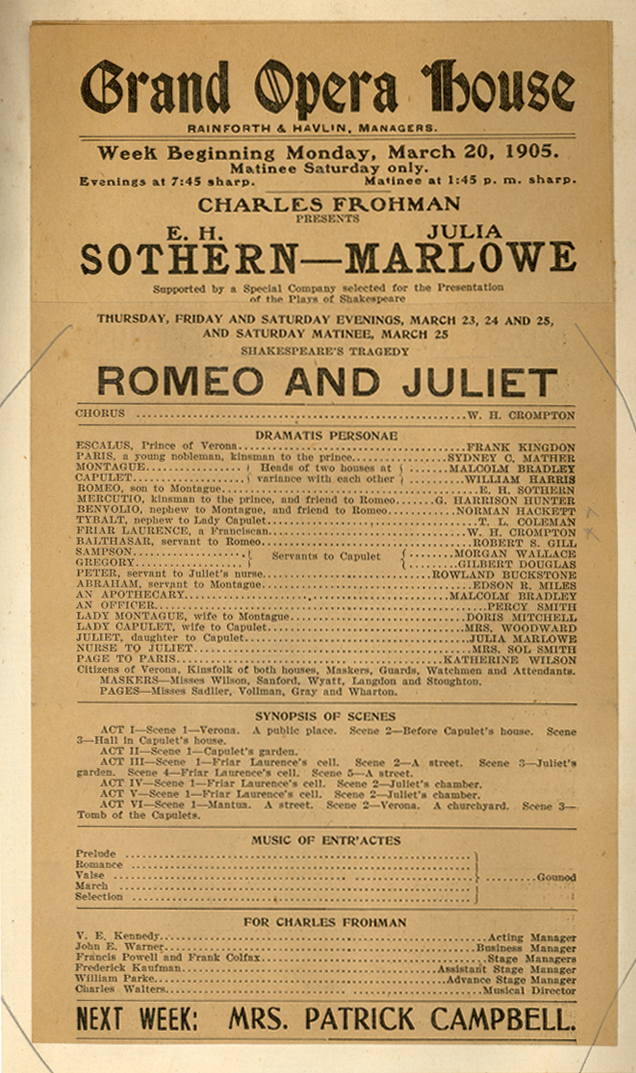

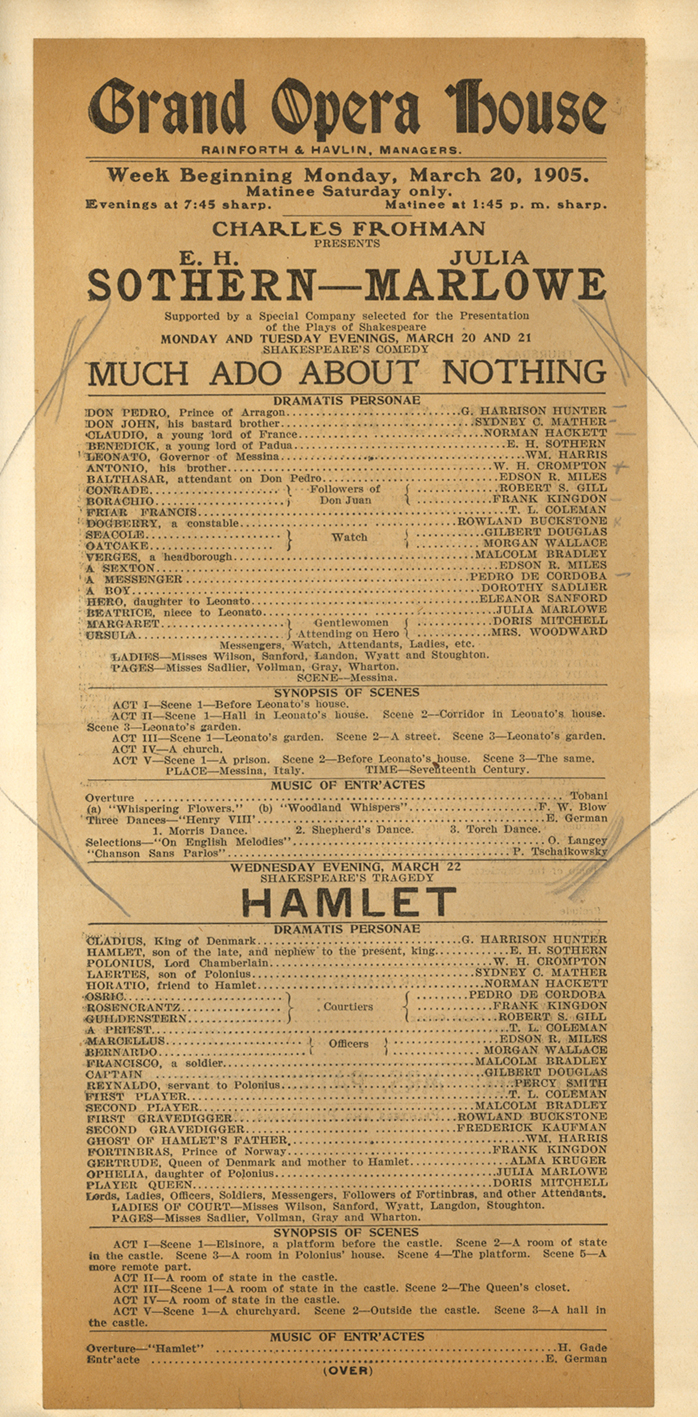

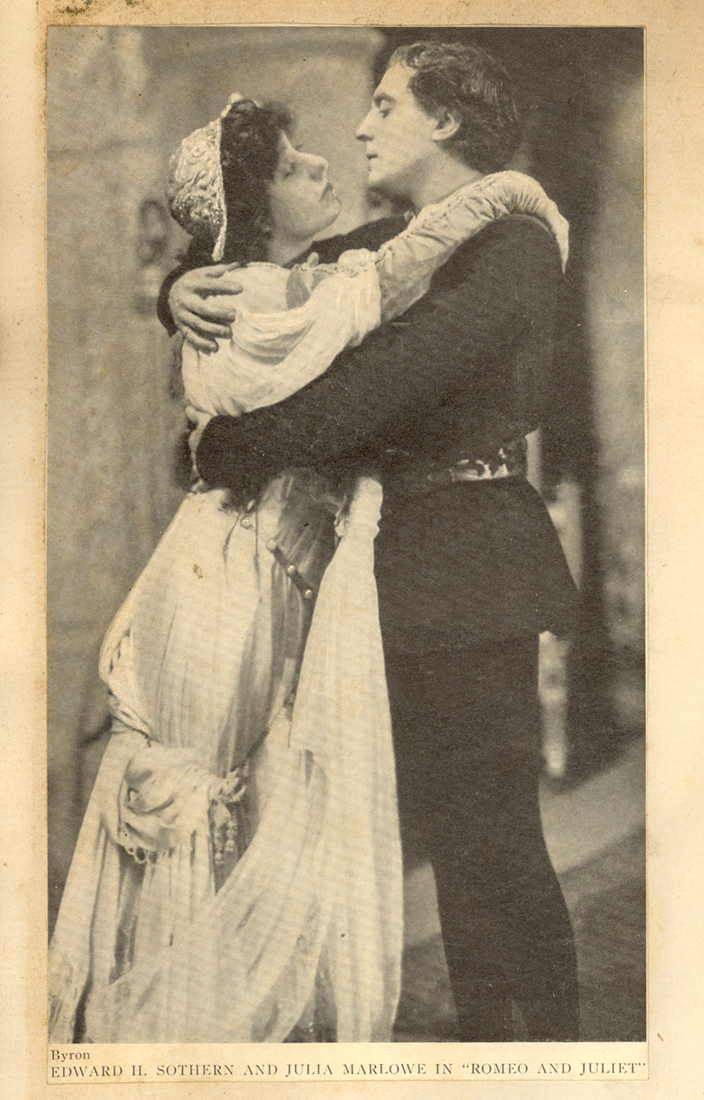

Marlowe continued her career, performing in numerous plays and receiving top billing. It wasn’t until 1904, however, that another notable partnership was created. E. H. Sothern, the son of actor E. A. Sothern, became the Romeo to Julia’s Juliet—making for the start of possibly the most memorable Shakespeare duo of the 20th century.

Marlowe continued her career, performing in numerous plays and receiving top billing. It wasn’t until 1904, however, that another notable partnership was created. E. H. Sothern, the son of actor E. A. Sothern, became the Romeo to Julia’s Juliet—making for the start of possibly the most memorable Shakespeare duo of the 20th century.

Together, Marlowe and Sothern first appeared in Romeo and Juliet as the title characters. Later, they moved on to the leads in Hamlet as Ophelia and the title character, and then Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing. They took their shows all over the United States, adding plays as they traveled. The two dissolved their company for a brief period between 1908 and 1909 after their contract expired because by then it made sense for the couple to pursue separate avenues. Fortunately, they reunited for a performance of Antony and Cleopatra in 1910 and finally, in 1911, the duo took their relationship beyond the stage and got married. Being two people of equal ambition, their relationship was regarded by friends as uniquely happy. They continued touring until Marlowe fell ill in 1924. Sothern still performed, but retired in 1928. From then until his death in 1933, Sothern continued his onstage presence as a lecturer with speaking tours, giving talks on Shakespeare—how to perform and the intricacies of the work.

Julia Marlowe lived until 1950, when she passed away in the Plaza Hotel at the age of 84. After the death of her husband, the Cincinnati-raised actress became somewhat of a recluse, only making a select number of public appearances. Her last appearance was to give the Museum of the City of New York a trunk of costumes which she and Sothern had used in their days of performing. The world, she was certain, would remember Julia Marlowe as long as Shakespeare is remembered—perhaps even beyond that time.

If you would like to learn more about Julia Marlowe, E. H. Sothern, or anyone else who might have graced Cincinnati with their stage presence, please give us a visit. Our hours are Monday-Friday, 8am-5pm. Call us at 513.556.1959 or send us an email at archives@ucmail.uc.edu. Don’t forget to check out our Shakespeare quadricentennial page on the Archives & Rare Books Library website at http://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/exhibits/shakespeare400/ or to like our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/ArchivesRareBooksLibraryUniversityOfCincinnati/ where there is always something Shakespearean being posted. You can also find us on Twitter at @ARBLibrary.