By: Kevin Grace

On December 3, 1907, an angry father wrote to the Board of Directors at the University of Cincinnati:

Gentlemen:

Enclosed you find a doctor bill for treatment of a fractured nose, rendered to my son Armin C. Arend, who was hurt in a flag rush on the 30th of October; the rush being aided and supported by the officials of the University of Cincinnati. I hope your Honorable Body doesn’t expect that I have to pay this bill since I, as well as my son, am opposed to flag rushes. Please take this matter into your hands, & judge for yourself who should pay this bill. Remember, that I paid tuition for this day, which is not given as a holiday in the School Calendar of the University of Cincinnati.

It is hard enough for me as a workingman to pay tuition let alone such foolish unnecessary expenses.

Yours Respectfully,

Julius Arend

3318 Bonaparte Avenue, City

The bill in question, for $5.00, was referred to the Board’s Law Committee, which quickly denied the father’s claim. As no further word was heard from Mr. Arend, presumably he chalked up the medical bill to an educational expense, like young Armin’s textbooks, but literally, a lesson in the “school of hard knocks.”

Because that is what “flag rush” was during the Progressive Era, a bloodsport of occasional broken noses, broken arms, concussions, and countless contusions and abrasions. A variation on games we know as “capture the flag” and “red rover,” flag rush was a heightened example of these, and was popular on college and university campuses around the country.

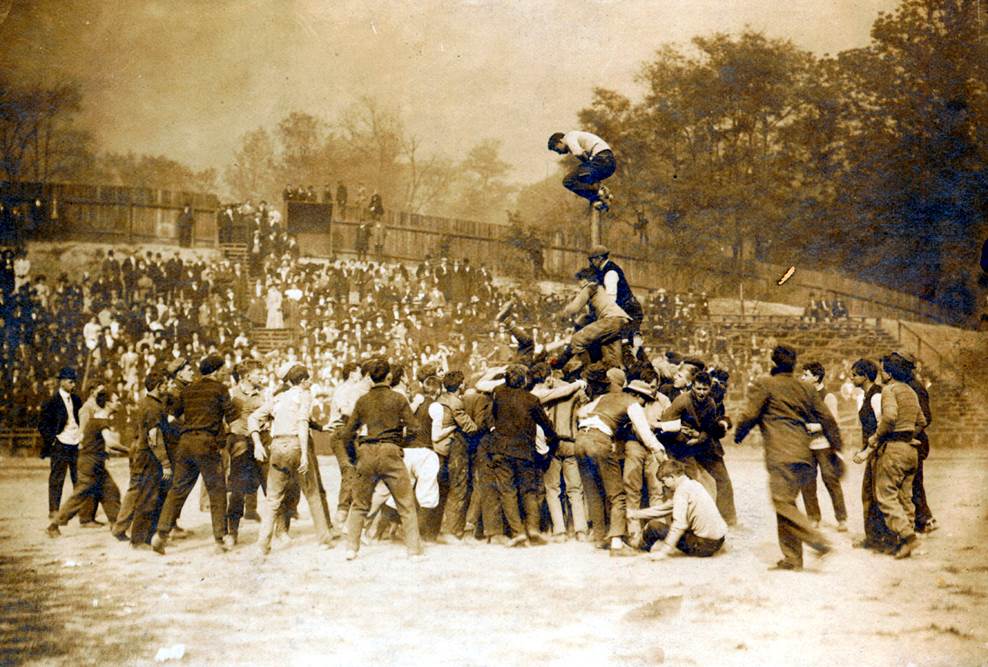

In flag rush, a leather banner or strip of cloth was attached to the top of a pole, which was then erected on a campus green space or field. The rush was typically initiated by a male undergraduate class, the freshmen, sophomores, juniors, or seniors. Once the pole was in place, the class would issue a challenge to another class to take the flag. For an example here, the juniors made the challenge to the sophomores. The juniors then locked arms in a circle around the pole, and waited for the charge of the sophomores to break through their ranks so one of their number could shimmy up the pole and rip off the banner and claim victory. The battles could be over in a few minutes, or a could last as long as five or six hours, depending on the strength and resolve of the combatants.

As one would expect in this confrontation between healthy young males, flag rush often resulted in a general melee. Fists were thrown, clothes were torn, elbows swung around to chins and foreheads, shins were brutally kicked, and opponents thrown to the ground. All to capture the “prize.” These flag rushes were conducted in front of a large part of the student body, including the coeds. It was male posturing and battle bravado all at once. In the end, when the fracus was over, those who were not inflicted with concussions and broken bones, proudly strutted about with their bruises and bloody noses as badges of honor and manliness.

When the challenge was proclaimed, often it came about at the expense of classroom instruction. As lecture halls, labs, and seminar rooms were filled with students during the course of a school day, someone from the challenging class would run through the main academic building at the University of Cincinnati, McMicken Hall, shouting that a flag rush was on. As one would expect, the rooms quickly emptied as students rushed themselves to witness the battle and professors were left standing with chalk in hand and a mixture of anger and frustration in the eyes.

Though flag rush began as an informal, unsanctioned sport, rule and procedures began to be put in place at the turn of the 20th century, along about the same time that college administrations were taking control of general athletics out of the hands of the students. Regulations were implemented that prohibited any male undergraduate under the age of 21 from participating without a signed waiver from his parents – apparently Mr. Arend’s complaint had some effect – and all battlers had to have had a recent physical exam.

As the rush became formalized, brightly colored tickets were even sold to spectators, with the printed rule that the ticket must be worn and visible on the person. Preparations became formalized as well as campus groundskeepers dug a deep hole to erect the pole and tamped the earth firmly around it. And, a watchman was sometimes appointed to guard the pole overnight lest the defending team greased it. Captains were sometimes chosen to determine strategies and set times were established for the event, rather than the classroom-emptying hullabaloo that was part of early rushes. Set numbers of students were selected for each team and the coeds, under umbrellas in inclement weather, madly waved class flags and gathered in clusters at the side of the battlefield with a “commissary” of bandages and refreshments in baskets at their feet. In fact, one account stated: “The girls of the two classes, according to ancient custom, have delegated committees to prepare refreshments to strengthen their masculine champions. It is understood that each class has also appointed committees to steal, if possible, and eat or otherwise destroy the commissary of the other.” Photographs were taken for school newspapers and yearbooks, and the results duly reported.

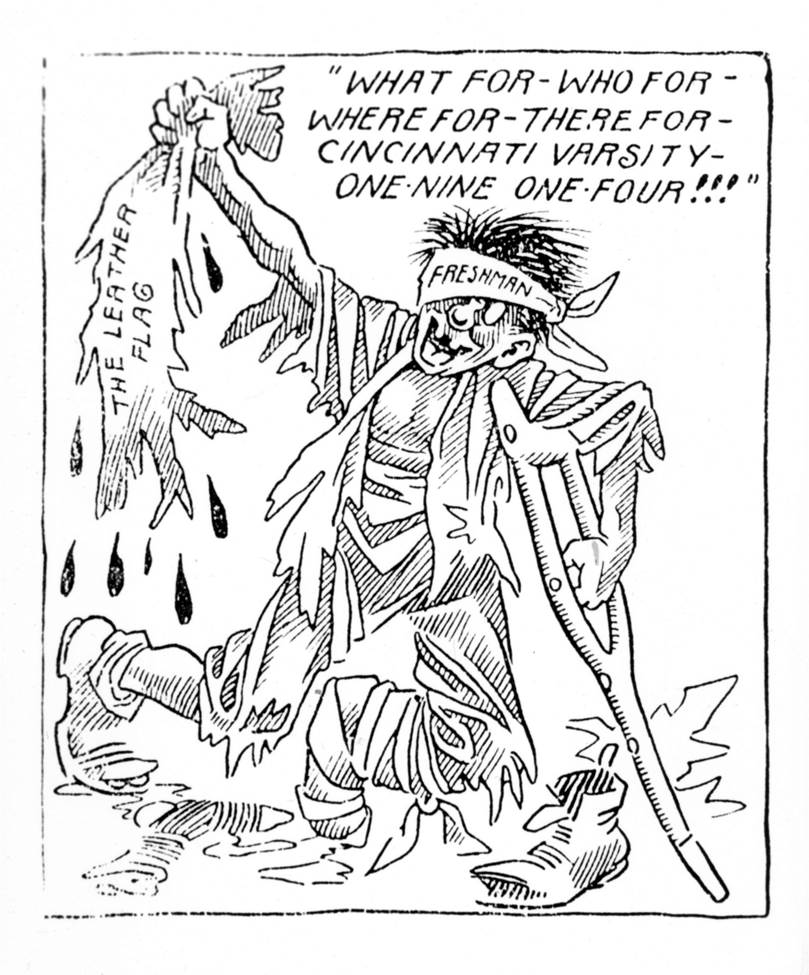

The language of the accounts emphasized the violence: “As Young Savages, Students Battled; Sophs Winners;” “ Hurt: Herman Haehnle, sophomore, scalp cut; Louis Crossley, sophomore, kicked in abdomen; Walter Day, sophomore, right leg; John Willis, sophomore, bruised about the head; Walter Mason, freshman, dislocated shoulder.” Regarding the last-mentioned warrior, it was “at first thought that he was badly hurt, but what do you think? He sustained only a dislocation of his shoulder. Then it was known for sure that the rules were all right…Besides getting only a dislocation of the shoulder, Walter got his first taste of college spirit. “

It is unclear when flag rush became a part of the college experience in this country, but through anecdotal evidence, some early 20th century university histories, and various student publications such as yearbooks and newspapers, it is reasonable to say that it began in the decade following the Civil War, and spread from the Northeast to the Middle Atlantic, Midwest, and Far West. Adalbert College of Western Reserve University, for example, had a flag rush tradition in the early 20th century, as did Michigan State, the University of Florida, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, the University of Rochester, and the University of Hawaii, just to name a few. In the case of Worcester, as violent as flag rush was, it actually replaced a more violent tradition called “paddle rush” that was played at halftime of football games. A large number of wooden paddles were placed at the 50-yard line, and at the signal, teams of students from opposite ends of the field would rush toward the center to grab as many paddles as they could, and to take paddles away from opponents. The result was predictable, so at least flag rush did not involve weapons. Flag rush certainly wasn’t present on every campus, but on a large enough number so that one can see its flourishing as a student tradition along with intercollegiate sports, hazing, class plays, dances, debate clubs, fraternities, and annual pranks. In other words, flag rush was an acknowledged event in the undergraduate’s academic years, and invariably viewed as an exercise in male bonding. At one point, flag rush was even fictionalized in a short story aimed at juvenile males called “The Class Rush” by Leslie Quirk and published in St. Nicholas Magazine in 1904.

It is perhaps no coincidence that activity such as flag rush coincided with the rise of the philosophy of “Muscular Christianity” applied to the well-formed young man. While the American concern with health and fitness, both morally, mental, and physical, dates to the first decades of the 19th century, by the Gilded Age, the societal patterns of what makes a well-formed man of civic responsibility was stepped up quite a bit. The literature on “Muscular Christianity” is considerable; the basic aspect is that in the 19th century, it was increasingly believed that America’s male youth – and future leaders – was becoming soft and complacent (although again, a not uncommon notion since the early 1800s), and in some measure, effeminate. One resolution to this dilemma was realized in the growth of the Young Men’s Christian Association, the YMCA, which began constructing gymnasia in earnest in the 1870s and 1880s and did its part for the Muscular Christianity credo of “a strong mind and a strong body will forge a strong spirit.” Expanded beyond the Christian credo, of course, was the idea that this “spirit” could be expressed in a manly, masculine approach to civic affairs and the expanded reach of American political influence. Puffing out one’s chest and wielding a big stick would mean one was a true example of a man.

The formation of colleges and universities from the Gilded Age into the Progressive Era reflected this philosophy of masculinity. When the city of Cincinnati formed its municipal university in 1870, two members of the prominent Taft family, Charles Phelps and Alphonso, wrote that the University of Cincinnati should be founded on the German model, emphasizing a “clubby” male atmosphere of examinations between professors and students, and stating that taxation should be applied to the funding of the university. They thought theirs was a good fit for Cincinnati’s heavily German community at the time, though the conservative citizens were not overly enthusiastic about tax-funding. In that way, however, the university was indeed founded. When Jacob Cox, a Civil War general and former cabinet officer took over as president of UC in the 1880s, he instilled in his faculty and students the idea that the city serves the university and the university serves the city. It is what men do. Cox maneuvered the university into being a confederation of existing private and public colleges in the city with the intent of producing in his classrooms and lecture halls a corps that was invested in civic affairs. While he left the city before his final plan was realized to move the campus from a small hillside just beyond the basin of the city to a wooded part of the Clifton neighborhood, Cox had set in motion the possibilities that athletics – given the additional room – could bring to academic instruction.

In the Progressive Era world where education was designed to improve the individual and thus improve the world around us – in politics, in morality, in urban living – feats of athleticism could be part of this training ground. Robert Baden-Powell’s Boy Scout philosophy had the focus of duty, responsibility, and preparedness for the unexpected. John Dewey’s pragmatic education looked at self-determinism leading to self-actualization, adjusting education to real-life experience and leading the individual outward. Education and experience would be on a continuum. On this continuum as well, for American colleges and universities, would be the physical making of a man.

In the Progressive Era world where education was designed to improve the individual and thus improve the world around us – in politics, in morality, in urban living – feats of athleticism could be part of this training ground. Robert Baden-Powell’s Boy Scout philosophy had the focus of duty, responsibility, and preparedness for the unexpected. John Dewey’s pragmatic education looked at self-determinism leading to self-actualization, adjusting education to real-life experience and leading the individual outward. Education and experience would be on a continuum. On this continuum as well, for American colleges and universities, would be the physical making of a man.

In Cincinnati, meanwhile, Charles Dabney became president in 1904 and for the next sixteen years, he would embody “pragmatic progressivism.” He came to the University of Cincinnati because he saw the opportunity for reforming an urban university in a city dominated by boss politics and the vagaries of public funding for higher education. Eliciting a promise from local political boss George Barnesdale Cox that Republican machine politics would not interfere, he began to create new colleges, the most important one of which was the College of Engineering in which he allowed a young dean, Herman Schneider, to create a cooperative education program that would become a model for most universities in the United States. It was learning by practical experience and experimentation. And, it was responsiveness to need. What did society need from its college graduates? Political leadership? Industrial leadership? Religious leadership? Military leadership?

It is the latter question that was answered by athletics and so-called “manly” endeavors. Theodore Roosevelt, America’s most visible and influential proponent of “the strenuous life”, wrote in 1900 about how sport makes boys into men in his essay “The American Boy”: “…the great growth in the love of athletic sports, while fraught with danger if it becomes one-sided and unhealthy, has beyond all question had an excellent effect in increased manliness. Forty or fifty years ago the writer on American morals was sure to deplore the effeminacy and luxury of young Americans who were born of rich parents…Nowadays, whatever other faults the son of rich parents may tend to develop, he is at least forced by the opinion of all his associates of his own age to bear himself well in manly exercises and to develop his body – and therefore to a certain extent, his character – in the rough sports which call for pluck, endurance, and physical address.”

The participants in a flag rush could not have phrased it better themselves. If they were fortunate enough to go to college then by all means, they should work to come out the better men for it. Apparently President Dabney of the University of Cincinnati agreed. In his comments following the flag rush of 1907, he said: “Good class games promote college spirit…The rush is conducted with the sanction of the faculty” (of course if they sanction it, it was because their lectures were no longer disrupted!) “and is in charge of competent officials who see the rules are carried out. The boys must have a contest in which skill and strength are brought into play. This is what the flag rush does.”

So we are left to consider what killed the tradition of flag rush on the college campus. By the ‘teens, flag rushes already had begun to die out as more and more parents, faculty, and education administrators complained about the brutish, disruptive violence of the sport. It never became an intercollegiate sport, and so while competition between classes was part of campus spirit, it could not measure up to pride in victory over another institution. And flag rush could not develop the rivalries, pageantries, and neat, military-like formations inherent in intercollegiate football games.

So we are left to consider what killed the tradition of flag rush on the college campus. By the ‘teens, flag rushes already had begun to die out as more and more parents, faculty, and education administrators complained about the brutish, disruptive violence of the sport. It never became an intercollegiate sport, and so while competition between classes was part of campus spirit, it could not measure up to pride in victory over another institution. And flag rush could not develop the rivalries, pageantries, and neat, military-like formations inherent in intercollegiate football games.

In some cases, flag rush came to be strongly discouraged by the institutions. For all it exhibited in “manliness” afterward with bruises and blood, flag rush still seemed to be purposeless violence, masochistically enjoyed the fighters and voyeuristically enjoyed by the spectators. One began to wonder what the real rewards were in such a spectacle. The discouragement by colleges and universities came in the form of attempting to substitute “like” activities such as push ball and tugs-of-war. For the former, push ball was an activity played on a football scrimmage field in which a huge inflated ball, six to eight feet in diameter, was pushed by two teams of students in trying to get it over a goal line. There was less likelihood of injury and still a commitment to mud and torn clothes. Tugs-of-war usually avoided the torn clothes, but sometimes not the mud when it was held over a campus creek or stream. Another innocuous substitute in some institutions was “mat rush,” which was little more than wrestling.

What really happened to flag rush, however, was the devastating events of the ‘teens. Mock war met the Great War. With the coming of World War I, the elements that constituted masculinity, manhood, and civic preparedness through higher education were re-evaluated. The practice of undergrads engaging in the rhubarb of rush suddenly seemed a bit trivial and perhaps even a bit insensitive to the specter of real young men dying by the hundreds of thousands. Followed by the 1918 Spanish influenza outbreak, which claimed an estimate of forty to a hundred million lives worldwide and nearly a million in the United States, exhibitions of manhood were better made through the regimentation inherent in “military” sports as football, in achieving an education and the degree that marked it for service to community, city, and country.