By: Bridget McCormick, ARB Student Assistant

One of the strengths of the rare books collection in the Archives & Rare Books Library is 18th c. British literature, encompassing poetry and drama, history, political treatises, social commentary, and homiletics among several genres. And, these works are complemented by materials for the same time period from the Continent, particularly France and Germany. Brought together, these important volumes highlight the Age of Enlightenment, that period of intellectual development and reasoning that took place in Europe between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. To “enlighten” is to provide knowledge or understanding to and indeed, this chapter of European history introduced significant developments in art, philosophy, science, and politics.

One of the strengths of the rare books collection in the Archives & Rare Books Library is 18th c. British literature, encompassing poetry and drama, history, political treatises, social commentary, and homiletics among several genres. And, these works are complemented by materials for the same time period from the Continent, particularly France and Germany. Brought together, these important volumes highlight the Age of Enlightenment, that period of intellectual development and reasoning that took place in Europe between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. To “enlighten” is to provide knowledge or understanding to and indeed, this chapter of European history introduced significant developments in art, philosophy, science, and politics.

With civic laws embracing ecclesiastical policies, the notion of practicing personal liberties or rights had many Europeans in conflict with religion – either at the hands of an unforgiving God or at the hands of the sometimes brutal church itself. A key result of the Enlightenment was a challenge to those traditional theological views. Questioning the existing power of the Catholic Church led to the development of Protestantism in the preceding Reformation and a growing appreciation for, if not tolerance, for new ideas. Additionally, as the Age of Enlightenment paralleled the Scientific Revolution, educational institutions began to develop curricula free of religious allegiances. Enlightenment philosophers stated that because humans possessed the wonderful God-imparted gift of reason, there was no limit on what the human race could achieve. The advances in science and technology of the time seemed to confirm this idea.

Prominent philosophers of the Enlightenment encouraged the movement’s followers to be skeptical of existing ideals accepted throughout Europe. Followers of the Enlightenment would have been considered “Liberals” of their day, as any challenge to previously accepted ideologies would have been regarded as radical and unorthodox. Some of the key thinkers of this period – Immanuel Kant, René Descartes, Isaac Newton, Samuel Johnson, David Hume, and Denis Diderot – especially emphasized philosophical ideas regarding reason, or the capacity for logical, rational, and analytic thought. Patrons of the Enlightenment movement were also encouraged to question the conditions of their daily lives and the precedents that surrounded them, such as the omnipresent influence of religion in society.

One of those leaders, the philosopher Kant, stated that the movement was the emergence of the human race from a state of immaturity to a state of maturity. He maintained that one should think autonomously, free from the rule of an external authority. Kant believed that if an action was not motivated by duty – acting in accordance with the demands of law, not for any particular goal – then it was without moral value. He thought that every action should have pure intention behind it – otherwise it would be meaningless. To Kant, the final result was not the most important aspect of an action, but how the person felt while carrying out the action and was the time at which value was set to the result.

This maturation in human reason imparted that each human has a certain set of natural rights. Examples of these include life, liberty, equality, property, security and the pursuit of happiness. In acknowledging these unalienable rights, Europeans began to delve deeper into questioning how their lives were governed. During the Enlightenment period, monarchies still operated under the principle of the “divine right of kings”, or that God appointed rulers with absolute right and exempted them from any wrongdoing.

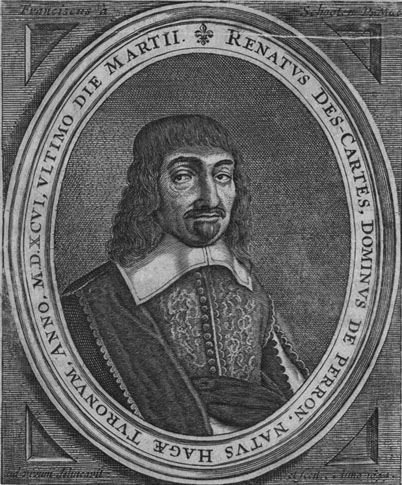

While the idea of questioning “the known” was perhaps the most pervasive theme of the Enlightenment, individualism also emerged as a primary motif with the advent of French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes. Descartes’s writings, fitting with the idea of individualism, often set his views apart from those of his predecessors. He conveyed the notion that individuals should be able to use reason to distance themselves from the herd mentality and guide their life affairs according to logic. Perhaps his most notable quote “I think; therefore, I am” attempted to form a basis for knowledge that would suit the radical doubt of the Enlightenment era. According to Descartes, the very act of doubting one’s own existence served as proof of the reality of one’s own mind.

Isaac Newton, widely considered to be one of the most influential scientists of all time, made multiple contributions to higher knowledge during the Age of Enlightenment. A preeminent mathematician, Newton was truly a pioneering academic figure as the creator of calculus, descriptor of universal gravitation, and originator of three laws of motion. Also a key contributor to the Mathematical and Scientific Revolutions, Newton’s revolutionary ideas about the universe became vital parts of Enlightenment ideology. His three-book series Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Latin for “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy“, marked the beginning of a great revolution for the world of physical science.

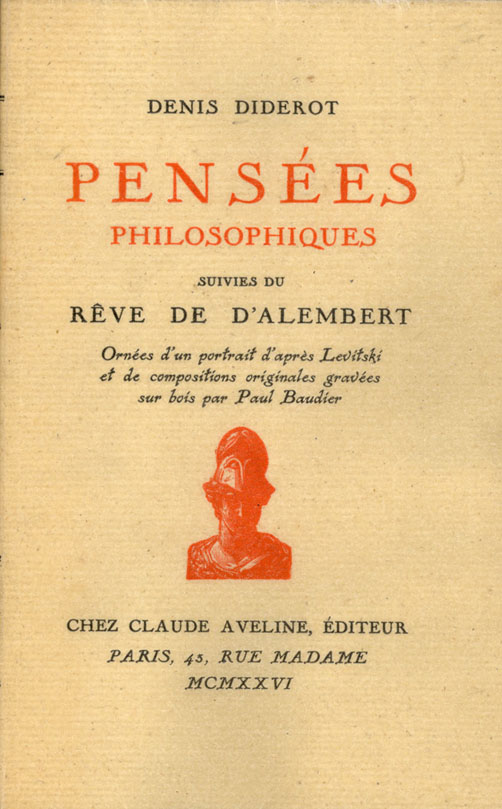

Denis Diderot was a French Philosophe and prominent figure during the Enlightenment. He is best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the Encyclopédie, a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772. In 1746, Diderot wrote his first original work, the Pensées Philosophiques. Translated in English as Philosophical Thoughts, in this book Diderot argues for reason to be related to feeling in order to establish harmony for the individual. At the time Diderot wrote this book, he was a deist,  which was a popular belief during the Enlightenment period. Deism – the view that a higher being exists but does not tell people what to do – states that people should rely on logic and reason and not traditions of a religion based on a holy book. Diderot’s Pensées Philosophiques contains a defense of deism and some arguments against atheism while also containing criticisms of Christianity. In his following work, Promenade du Sceptique, or The Skeptic’s Walk, a deist and an atheist have a dialogue on the nature of divinity. The deist gives his argument, while the atheist says that the universe is better explained by physics, matter, and motion. Quite the controversial work, Pensées was briefly published until 1830, when it was seized from Diderot by local police.

which was a popular belief during the Enlightenment period. Deism – the view that a higher being exists but does not tell people what to do – states that people should rely on logic and reason and not traditions of a religion based on a holy book. Diderot’s Pensées Philosophiques contains a defense of deism and some arguments against atheism while also containing criticisms of Christianity. In his following work, Promenade du Sceptique, or The Skeptic’s Walk, a deist and an atheist have a dialogue on the nature of divinity. The deist gives his argument, while the atheist says that the universe is better explained by physics, matter, and motion. Quite the controversial work, Pensées was briefly published until 1830, when it was seized from Diderot by local police.

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher with an open dissatisfaction for the existing dictionaries of the Enlightenment period. With his 1739 work, A Treatise of Human Nature, Hume strived to create a total naturalistic science of man that examined the psychological basis of human nature. Against rationalists – those who hold that reason is in itself a source of knowledge superior to and independent of sense perceptions – Hume held that passion rather than reason governs human behavior. Beginning the work when he was just 23 years old, Hume’s Treatise is now regarded as one of the most important works in the history of Western Philosophy. Hume was also a sentimentalist, which is a moral sense theory holding that distinctions between morality and immorality are discovered by emotional responses to experience. As a believer of this idea, Hume held that ethics were based on emotion rather than abstract moral principle, famously proclaiming that “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.”

Samuel Johnson was an English poet and critic who, as a man of sturdy prejudices and who hated infidels, mistrusted metaphysicians like Newton and had no high opinion of philosophes like Diderot. Instead, Johnson pioneered the Enlightenment in a less anti-establishment way. His deep love for the church and his respect for the clergy set him apart from the strident anti-clericalism and established intellectual circles. While he did not push boundaries of society in the fashion of his peers, Johnson expanded public knowledge in other ways. His work, A Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1755, has been described as “one of the greatest single achievements of scholarship.” In 1741, David Hume claimed: “The elegance and propriety of style have been very much neglected among us. We have no dictionary of our language, and scarce a tolerable grammar.” Johnson’s Dictionary offers insights into the 18th century and “a faithful record of the language people used.” More than a reference book, it is a work of literature that has had a far-reaching effect on modern English. It was the primary work that brought Johnson popularity and success.

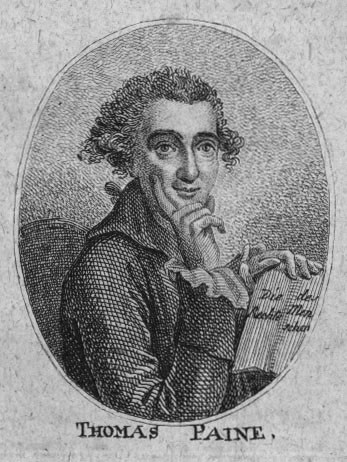

While the Enlightenment was a broad movement that developed gradually – it had no exact starting date – most historians place the beginning between the mid-17th century and the beginning of the 18th. The movement died out in the early 19th century as the Romantic period began. However, its influence had already spread to the United States where it attracted followers like political theorist Thomas Paine and future president Thomas Jefferson.

Today at the University of Cincinnati, there are a number of professors in various departments who are interested in the Age of Enlightenment and what lessons and inspiration it still continues to bring to intellectual development and critical thought.

To discover and use the Enlightenment rare books in the Archives & Rare Books Library, please call us at 513.556.1959, email us at archives@ucmail.uc.edu, visit us on the 8th floor of Blegen Library between 8:00 and 5:00, Monday through Friday, look for us on the web at www.libraries.uc.edu/arb.html, or follow us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/ArchivesRareBooksLibraryUniversityOfCincinnati/.

And we will be exhibiting some of our Enlightenment holdings in ARB this fall, showing them alongside the massive 1749 London map that hangs in the reading room, a map that is one of the outstanding cartographic achievements of the 18th century.