In my previous blogs, I have explored the history of Cincinnati’s House of Refuge and the records of the institution that are still available. Throughout my journey, I have been struck by the number of homeless children and children without adequate homes who were placed in this juvenile detention facility. One of the questions that I have been exploring is why these children were placed in the House of Refuge and not in another institution. My first thought was that there must not have been anywhere for these children to go, but a search for orphanages and other institutions in 19th Century Cincinnati has revealed that there actually were institutions that cared for children who had been abandoned, neglected, or whose parents were simply unable to care for them. So why were children who were not juvenile delinquents living in the House of Refuge? It seems that one reason may have been because there was not a standardized or centralized way of dealing with neglected, abused or homeless children in the city.[1]

Services for children in need in 19th century Cincinnati were controlled by different entities and the placement of children was often influenced by religion, ethnicity, and race. Orphanages in Cincinnati were almost exclusively privately run and they were often affiliated with a particular religion. Some took in children who were homeless or children who the administrators felt were not adequately cared for by their parents, but other institutions only accepted orphans whose parents were either both deceased or whose parents were contributing members. In addition, only a few institutions in 19th century Cincinnati, including the House of Refuge, accepted African American children. A closer look at a few of these early Cincinnati orphanages shows how their services differed and overlapped.

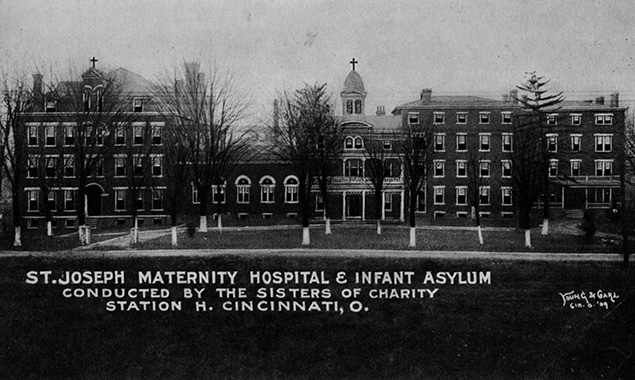

St. Joseph Maternity Home and Infant Asylum from the Hoffman Postcard Collection at the UC Archives and Rare Books Library

Religious groups were among the first to sponsor orphanages in Cincinnati. The earliest orphan asylum in Cincinnati was Catholic and was established by the Sisters of Charity shortly after their arrival in the city. St. Peter’s Orphan Asylum opened in October of 1829, and focused solely on the care of girls. The asylum did welcome both Catholic and Protestant children, but, with a growing Catholic population in the city, the fact that the sisters took in Protestant children caused tension with Protestant groups who feared that the children were being converted to Catholicism.[2]

It was not until 1837 that a Catholic orphan home for boys opened. In 1837 Father John Martin Henni, the Pastor of Holy Trinity Church, founded St. Aloysius. Even more specialized than St. Peter’s, St. Aloysius, served as an asylum for German Catholic boys. To raise funds for the orphanage, Father Henni began publishing Wahrheitsfreund, the first German Catholic newspaper in the United States. The boys were originally housed in private homes, but in 1839 the orphan asylum opened a location on West Sixth Street.[3] Several other Catholic institutions serving children in Cincinnati were founded later in the 19th century including a home dedicated to the care of infants.[4]

A semi-public orphan asylum that did not cater to specific religious groups had opened in Cincinnati in 1832, after a flood and a cholera epidemic had overcome Cincinnati within the span of a few months. Approximately two percent of Cincinnati’s population died during this cholera epidemic alone.[5] The poorest residents of the city living closest to the river were the hardest hit. Several prominent women who had raised money to help those affected by the cholera epidemic decided to use their remaining funds to open an orphan asylum to assist children whose parents had died. [6] The Cincinnati Orphan Asylum was incorporated on January 25, 1833 and twelve women were appointed to oversee the asylum.[7] They would take in a total of 78 children in their first year. The children were described as a combination of “true orphans, children who had been neglected or deserted by their parents, and ‘waifs’ picked up by the Township Trustees.”[8] The Cincinnati Orphan Asylum did accept some children who simply did not have proper homes or who were homeless, and could have served as an alternative to the House of Refuge.

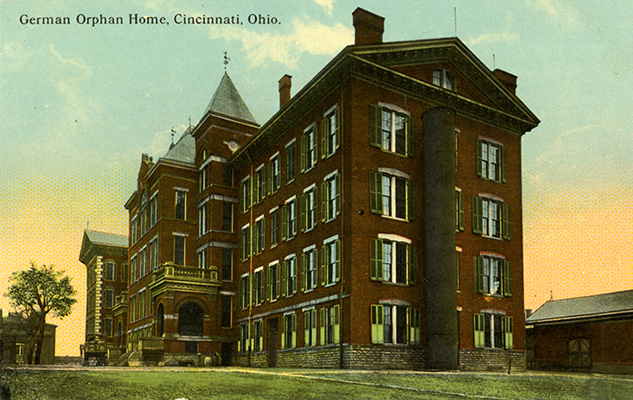

General Protestant Orphan Asylum, Cincinnati, from the Hoffman Postcard Collection at the UC Archives and Rare Books Library

In contrast, another orphanage established after a cholera epidemic was more discerning in determining which children to accept. The General Protestant Orphan Home was established after a second cholera epidemic in 1849. In Cincinnati alone, 6,000 people or approximately five percent of the population died during this epidemic.[9] The First German Protestant Aid Association of Cincinnati met on July 29, 1849 in the North German Church and afterward established the German General Protestant Orphan Society to raise funds and establish a home for orphaned children. Construction of the orphanage in Mt. Auburn began in 1850 and the orphanage opened in 1851. The organization accepted full orphans and children of single parent households if their remaining parent was unable to care for them but only if the parent was a member. Each child who entered the home was required to be baptized and to attend school.[10]

The first orphanage dedicated to the care African American children was the Colored Orphan Asylum. It was established in 1844 by Lydia B. Mott and an association of African American and white men and women.[11] The Colored Orphan Asylum accepted both children whose parents had died and children whose parents were unable to provide for them. The asylum was funded through donations, member subscriptions, and benefit events.[12]

One of the most influential institutions for the care of dependent and orphaned children in Cincinnati found its roots in the Children’s Aid Society, also called the Industrial School, which was established in 1859. The original industrial school opened on Water Street in December of 1859. It served as school and operated the equivalent of a daycare for infants. The Children’s Aid Society also began taking in children who needed homes. Following the guide of the New York Children’s Aid Society, they worked to find homes in the country for the children. By 1863, the Children’s Aid Society was struggling and lost the abandoned school house they were occupying on Race Street.[13]

In 1864, a group of Quaker women who had also been involved in the Children’s Aid Society, Hannah Smith, Margaret Hinckman, and Hannah Shipley, began the Penn Mission Day School in the Penn Mission Building on Park Street. The Penn Mission Building also housed the Penn Mission Sunday School started by Murray Shipley.[14] In April of 1864, they began taking in children without suitable homes and by the fall they had accepted 13 children. The name was changed to The Children’s Home on November 29, 1864. A Board of Lady managers was appointed to take care of the day-to-day operations and a 10 men were appointed to the Board of Trustees.[15] The Children’s Home would continue the goals of the Children’s Aid Society and seek to find homes in the country for the children in their care, but the fact that they concentrated their efforts on areas of the city that were populated by Irish and German Catholic immigrants helped feed into an already existing a mutual distrust between Protestants and Catholics.[16] This mistrust also influenced where children in need were placed.

These were not the only institutions for children in need in 19th Century Cincinnati, but they are among the earliest. Looking at the variety of their missions and the numbers of children that these institutions served makes it even more concerning that so many dependent children ended up in the House of Refuge. It does appear though that the competing missions of these institutions and the fact that the managers of the institutions could determine who they would and would not accept may have left some children with the House of Refuge as their only option.

If you are interested in learning more about Cincinnati orphanages, records do still exist for many orphanages in Cincinnati-area archives. The Hamilton County Genealogical Society maintains a list of repositories that hold the records of Cincinnati area orphan asylums on their website: https://hcgsohio.org/cpage.php?pt=69 .

[1] Steven Anders details the development of many child welfare institutions and the development of forms of public and private assistance in his PhD dissertation: Steven Edward Anders, “The History of Child Welfare in Cincinnati,” (PhD. dissertation, Miami University, 1981).

[2] Judith Metz, S.C. “The Sisters of Charity in Cincinnati, 1829-1852.” Vecentian Heritage Journal 17, no. 3 (Fall 1996), http://via.library.depaul.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1175&context=vhj (accessed May 22, 2018).

[3] Deb Cyprch, “Cincinnati Orphan Asylums and their Records, Part One: Founded Before the Civil War,” The Tracer 32, no. 1 (February 2011): 18.

[4] Deb Cyprch, “Cincinnati Orphan Asylums and their Records, Part Two: Founded After 1852,” The Tracer 32, no. 2 (May 2011): 33; 48-55.

[5] Matthew D. Smith. “The Specter of Cholera in Nineteenth-Century Cincinnati.” Ohio Valley History 16, no. 2 (Summer 2016), http://rave.ohiolink.edu/ejournals/article/346787962 (accessed May 22, 2018)

[6] Robert L. Black. The Cincinnati Orphan Asylum (Cincinnati? [n.p.], 1952 [self published?]

[7] Black, 17.

[8] Black, 30.

[9] Smith, 31.

[10] Christin Hall and Natasha Rezaian, Cincinnati’s General Protestant Orphan Home: Beech Acres Parenting Center (Charleston, South Carolina: Acadian Publishing, 2011).

[11]Cincinnati Museum Center, “Finding Aid for the New Orphan Asylum for Colored Children Collection” (Cincinnati: Cincinnati History Library, n.d.), http://library.cincymuseum.org/archives/mss1000-1099/Mss1059-register.pdf (Accessed May 22, 2018)

[12] An overview of the Colored Orphan Asylum is available in: Nikki Taylor, Frontiers of Freedom (Columbus, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2005), 128

[13] Anders, 123-125.

[14] Norman W. Paget, Dorothy E. Paget, and Vincentia T. Woermann, “An Historical Review of the Children’s Home of Cincinnati, April 1, 1864 through December 31, 1865” (Cincinnati: The Children’s Home of Cincinnati, 1970).

[15] Dan I. Hurley, One Child at a Time: A History of the Children’s Home of Cincinnati, 1864-1989 (Cincinnati, Ohio: The Children’s Home of Cincinnati,1990), 10-14.

[16] Hurley, 18-22.