Leslie Schick poses in the Walter C. Langsam Library, 2018

This December, the University of Cincinnati Libraries will say goodbye to a valuable employee and one that has played a central part in great change in the Libraries. Leslie Schick, senior associate dean of library services and director of the Donald C. Harrison Health Sciences Library, will be retire at the end of UC’s fall term.

Leslie has enjoyed a long, storied career with the university, beginning as an information services librarian with UC’s Health Sciences Library.

“When I started, everything was print. We had card catalogs – none of the local, regional or international online library catalogs we do now,” Leslie remarked. “When people would come looking for a particular book, if we didn’t have it in our card catalog, meaning we didn’t own it at the Health Sciences Library, as a reference librarian I’d pick up the phone and call other libraries. If it was a nursing book, for example, I would call the Raymond Walters Library (the former name for UC Blue Ash) to see if they might have it because they had a nursing program. You would have to think about who at the university might have this book and then you would call that library. It was our own version of OhioLINK or Interlibrary Loan. Looking back…the whole world has changed.”

Leslie with her fellow reference librarians in the 1980s

Over the course of her career, Leslie has seen an incredible amount of change. This nurtured a deep appreciation for her colleagues, one that would serve her well as her responsibilities increased and she took on roles in library management. She watched as new waves of talent joined the library, as well as those times when years of institutional knowledge were lost to retirements.

“For some people, the change from print to online was more difficult. We had the most amazing reference librarian at the Health Sciences Library when I started, Ruth Epstein. She’d come from the hospital library, which was consolidated into the medical center libraries when it was formed in 1974. Whenever someone had a difficult question in our library, she’d be the one to find the answer. We had a site visit for one of our IAIMS grants (Integrated Advanced Information Management Systems) back in the 80s, and one of the members of the site team asked her one the most awful reference questions anyone could think of. After she found what they were looking for they told her that they’d asked the same question at over 25 academic health science libraries in the country and she was the only person who’d given them an answer. She read everything, every issue of 15 to 20 medical journals – she said that was how you kept on top of things. That was the old-school way. When we started putting a computer at our reference desk and moving away from the traditional card catalogue, she retired…she wasn’t able to deal with the change.”

Giving a demo of NetWellness to then Governor Voinovich at Middletown Public Library in the late 90s

Later in her career, Leslie was a part of the grant team that secured funding for the Ohio Valley Community Health Information Network, which became Netwellness.

“It was a grant to provide quality healthcare information to consumers, and we wrote and received the grant before the web was really out there. It had been invented, but it was still at the CERN in Switzerland, not a part of our everyday lives in 1995. We had about 30 different sites around the Greater Cincinnati Area where we installed computer workstations including in public libraries and pharmacies. We actually had to buy computers and provide CDs of the materials they were showing. Then, within a year and a half, we had to reinvent the whole project to make it work on the web. It was such a powerful lesson in terms of changing how we dealt with information.”

“Back in the day, before we had the web and systems like Medline Plus and NetWellness, we had a lot of consumers come to the library. The public library would actually refer people to us, partly due to their limited resources, and partly because they didn’t want their librarians spending two hours with somebody trying to diagnose them. A lot of interesting people would come into the Health Sciences Library looking for information for themselves or their family members. People would come into the library in their wheelchair or with their IV pool attached and their hospital gown on looking for a diagnosis. It was a different world.”

When we created NetWellness, the first consumer health site in Ohio, I felt like it was the greatest service to mankind – certainly to the Greater Cincinnati community, but beyond that because it was on the web and people could find information about health conditions. We had an ask-an-expert feature where users could ask questions and medical professionals responded to all of the legitimate questions.”

Leslie, circa 1999

The world has changed a lot over the last 20 years, but NetWellness is still a trusted resource in Ohio. Its creation has done a great deal to serve the public, and freed up some much needed time for the Health Sciences librarians to focus on serving the faculty, staff and students of the medical center with their whole plethora of needs.

It was a response to some of those needs that led to the next highlight of Leslie’s career. Over a span of eight years, she led a team of Health Sciences librarians to help the National Library of Medicine create MedlinePlus. Like NetWellness, MedlinePlus was designed to help consumers access authoritative health information sources. When Leslie and the UC team joined the MedlinePlus team, there were about 30 health topics. Eight years later, there were over 800 health topics on the system.

“Back in the day, when medical faculty or students were doing research, they would either sit down with Index Medicus and spend hours and hours looking for something, or they’d come ask a librarian to do a Medline search for them. That was our big business. I’d spend two and a half days a week just doing research for people – usually about 50 a day. Then around ‘86 or ‘87, we started developing things that would allow people to do their own searching. We had a system at the Health Sciences Library, a homegrown system that used OVID search software. We loaded up a subset of Medline tapes from the National Library of Medicine, about 150 journals that were indexed, to our system MIQ – Medical Information Quick. Once that got popular it was easier to find a balance. We were still doing a lot of searches for people, but a lot of them liked searching for themselves. Then systems like MIQ went away and PubMed became available, giving people access to the entire Medline database. Our role changed again, from being a gateway for searches to training people how to do their searches the best way possible. We still do some searching today, but now it’s very complicated systematic reviews and meta-analyses.”

Leslie presenting at the Early Summer Institute

From 1999 – 2015, Leslie coordinated the Early Summer and August Instructional Technology Institutes for UC faculty. Each summer, 20 faculty members would spend a week with a team of librarian instructors to learn many different technologies that could help the faculty with their teaching, research or other scholarship. Leslie taught regularly in the Early Summer Institute, including sessions on Animoto, recording and editing digital sound files, and in the early years of the program: Blackboard and advanced PowerPoint among other topics.

“One of the best opportunities I had in my career was teaching masters level students in the College of Nursing, called ‘Nursing Informatics for Scholarly Inquiry’.” It was a three-credit hour course required for all masters of nursing students. I was scared to death when I first started teaching. I got confidence when I was at the College of Nursing and began to teach on a regular basis. I love teaching, it was one of my favorite things I got to do during my career here at UC.”

2008 brought on a lot of change for the Health Sciences Library, both physically and organizationally. It started when UC moved from a two-provost system to a single provost system. All the colleges at the Medical Campus, except for the College of Medicine, began reporting to the provost. The Health Sciences Library was also impacted.

Prior to 2008 the Health Sciences Library and Academic IT were a combined organization referred to as AIT&L. With the merger, AIT&L was split with the people that were library reporting to UC Libraries (then university libraries) and IT combining with UCIT (now IT@UC). There was one group that provided IT customer service that primarily supported the dean’s office and medical education and they were permitted to remain a single unit, but half of the employees were UCIT and half were library.

At the opening of the new Donald C. Harrison Health Sciences with then dean Vicki Montavon and the library’s namesake, Dr. Donald C. Harrison, former Senior Vice President and Provost for the Medical Center

Shortly thereafter, the Health Sciences Library staff experienced another substantial change when they moved into the new Donald C. Harrison Health Sciences Library, housed between the new CARE/Crawley Building and the Medical Sciences Building. They were once again united as a staff after being separated across seven different locations for almost four and a half years during the building’s construction.

“Our challenge during the years of construction was to keep our culture together, to make people feel like they were still a part of one organization. It was hard, but there was so much excitement about the new library space and moving back in, and that’s what kept us going. After we were settled in, however, the reality of what was happening in terms of us trying to fit into the University Libraries organization the way we wanted, was difficult.”

The transition was at times a rocky one. Marrying two large identities was an arduous task made more difficult by the distance between east and west campus.

“It was a hard time for the Health Sciences Library people. Our previous boss lost his job, and no one was sure if I would be named director or not. There was a lot of uncertainty. The cultures of the Health Sciences Library and UC Libraries were very different, they are still rather different. It was a hard transition, but one that we made it through.”

At the opening of the new Health Sciences Library with UC Libraries Communications Director Melissa Cox Norris

Leslie’s experiences have given her a great deal of insight, along with an ability to track the progress of the libraries and their staff, as they grappled with the ever-evolving needs of academia and the more targeted needs of their individual user bases.

“I think almost everyone we have on staff has moved forward. It isn’t like it used to be 30-35 years ago. Some people have embraced technology and learned to exploit it more than others, but it really depends on what your job is and where you’re working. There are some libraries where the print collection is still their primary focus. In the Health Sciences Library, we hardly buy anything in print anymore as our users don’t want the print. They want everything accessible from their phone, so if they’re at a patient’s bedside they’ve got it; nobody has time to run back and forth. Clinicians have a pressure to see a certain number of patients. They don’t have time to run to the library or to even get on a different device; whatever they have in their pocket, they need to have access to everything. I think that technology adoption has varied wildly in libraries. We all use it to a certain extent, but there’s more pressure in the STEM fields to be right on top of it because that’s where the disciplines are. In many respects, the Health Sciences Library today and tomorrow have to reflect the disciplines they support. We have to change in the way that teaching in the Health Sciences is changing.”

Some of the most drastic technological changes they’ve seen have been from the College of Nursing. Their whole curriculum is now delivered on iPads. “Our librarian who supports the college, Emily Kean, is now teaching a course in the Doctorate of Nursing Practice Program (DNP). The course is on iBook and made for iPads. As Dean Wang always preaches, we want to make the library experience for online learners the same as it is for our on-campus learners. We’re not there yet, but are getting close I think, especially in Nursing, Emily is doing a fantastic job.”

As for the future of Health Sciences Libraries, Leslie sees the National Library of Medicine’s recent strategic plan playing an important role.

“It (the strategic plan) is really focusing on a platform for biomedical discovery and data-empowered health. That’s going to influence how academic health sciences libraries view themselves and their mission and move them toward enabling people to discover and also use data. I first heard the term ‘evidence-based medicine’ about 25 years ago. At the beginning, it meant that you’d find the best evidence in the medical literature to the support decisions that you’re making. Now the NLM is saying that the literature itself is not enough, that there needs to be data behind the studies, which we (the libraries) will provide easy access to.”

While the NLM will influence and provide guidance to academic Health Sciences Libraries for their future direction, those same libraries also need to reflect what’s going on in their own communities.

“What we do at UC may not work at UK or OSU. We have to be in tune with where our colleges are going and have a multi-pronged approach, because they all have multiple missions of teaching, research, community engagement and outreach. We have to constantly look to see where they’re going and how we match up with services and resources to support all of them. I’ve been on curriculum committees in the College of Medicine for a long time, and that’s helped tremendously, at least in keeping me informed of what’s going on with curriculum. Tiffany Grant, the assistant director for research and informatics, keeps an eye on what’s going on in the research area in the College of Medicine. We have to reflect the people we need to support. It’s important to have conversations with people.”

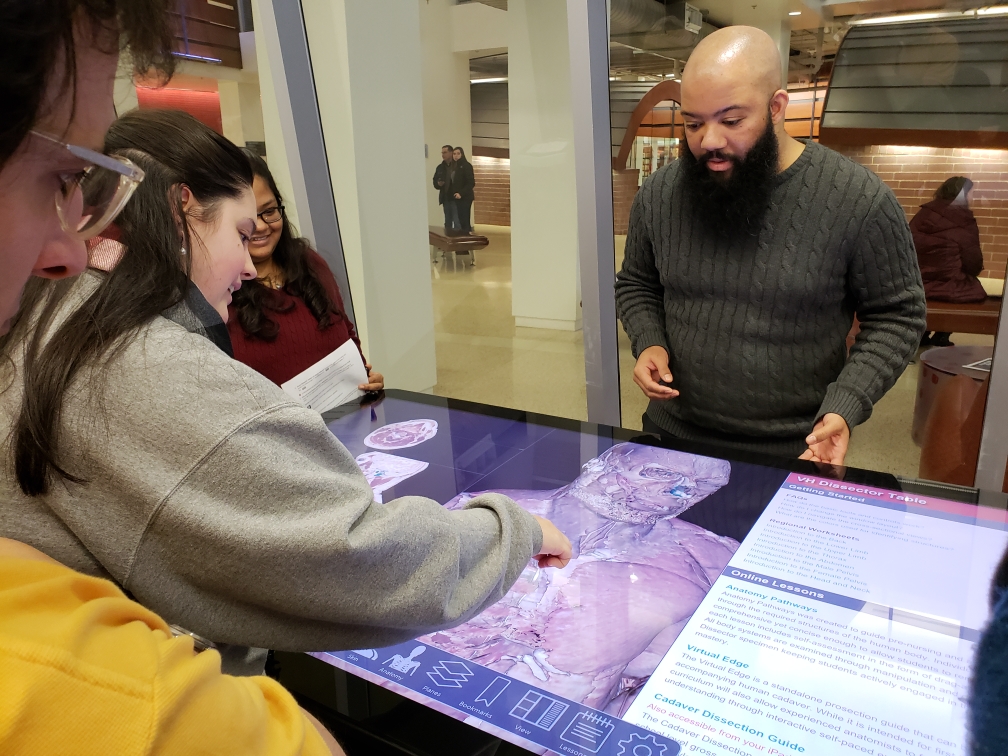

Virtual dissection table in the Health Sciences Library

One example of this type of collaborative conversation occurred over the library’s newly installed virtual dissection table. After years of applying for grants to fund the table, the idea resurfaced when Leslie began looking for ways to create a fresh, first impression for the glassed-in library entrance. With the College of Medicine’s accreditation with the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) looming, the library needed to make a strong statement, one that would grab people’s attention and engage the community. They did some research, received some updated quotes and then reached out to the anatomy faculty to make sure they were on board.

“We had a really fascinating series of meetings with them. During the first meeting they were excited, but wanted to do more hands-on research. One of the medical education faculty knew people at Mt. Saint Joe and they had a table, so they went over to take a look. At the next meeting they were less enthusiastic. They weren’t sure it was something they could use in their curriculum and said “if you want to get something flashy, this will do it, but don’t count on us to ever use it.” I thanked them for their honesty and input, but got the distinct impression they had spoken among themselves after the first meeting and had come to some wrong conclusions about what we were doing. We were seeing the table as a supplemental tool, obviously no replacement for cadavers and other traditional forms of dissection. Students could use the table to work on dissections when they labs weren’t available, not to mention any of its numerous other functions. After more discussion they were surprised to find we weren’t forcing them to change their curriculum, or asking them to find ways to utilize the table immediately within the current semester. We explained that they would have a year to work with the table, remote into it from their classroom, learn what it was capable of doing. All of the sudden they were excited again, and giving us more, new creative solutions we could also pursue.”

“It’s important to have these discussions with your faculty, because you don’t want to end up with missed opportunities. We are managing the library and its resources for our users – it’s not our collection and it’s not our library. My former boss, Roger, used to say that all the time, and he was absolutely right. If you keep that in mind, you’re less likely to make a wrong decision, because you’re going to be having those conversations, and I think that’s one of the most important things for leaders to remember. We’re just curators for a short period of time.”

In 2013, a search committee was named to find a new dean for UC Libraries. Leslie was on it.

Xuemao Wang and Leslie Schick

“I knew immediately when I met Xuemao (Wang, UC Libraries current dean and university librarian) that he was the right person for the job. From the first day he walked in, it was obvious that he understood what an academic Health Sciences Library was, what it should be doing and its value to the overall structure. When Xuemao came to UC, he brought a new vision and new ideas. I can remember the first week when we (senior leadership) met with him, he asked us what we were doing in specific areas – Did we have an Institutional Repository? We were exploring Data Management services? Had we hired a group of Informationists? He knew where academic libraries were currently and where they were going. He immediately saw that we needed to start developing new roles for our librarians, especially in STEM. He kept saying that we needed to be a 24×7 academic research library, that despite our size we could and would find our niche. That really resonated with me and energized many of us.”

After meeting with the organization, observing its culture, and learning about each library and unit, Dean Wang set out to pursue a new Strategic Plan. He put Leslie in charge of the Strategic Plan Steering Committee – another highlight in her career.

“One of the things he (Xuemao) often talks about is courageous leadership. When you have someone who exemplifies what he’s talking about, it’s a lot easier to follow. It’s been easier to make difficult decisions because he always has our back.”

In November 2016, Leslie was promoted to senior associate dean of UC Libraries. Her new responsibilities included providing operational oversight of UC Libraries and acting on Xuemao’s behalf within the libraries and for UC senior leadership meetings, initiatives and events.

“The biggest change was having office space in Langsam, with the expectation that I would be there over half the time. The way I think about it, I went from having a portfolio of the Health Sciences Library and the science libraries, along with some responsibilities for leading the organization, to being that person who took over when Xuemao was not available- mostly due to his hectic travel schedule. I had the opportunity to be involved with many more things in the life of the organization. It’s been a challenge and an honor.”

“I also help to mentor the new leaders coming into the organization. I feel like that’s been the most important thing for me in this role, mentoring the new leaders, along with other people. I’ve mentored people I feel like have potential, and I’ve tried to spend enough time with them to help them achieve that potential.”

“It’s been a great opportunity to represent Xuemao at the Council of Deans meetings, to get a sense of the differences, provost to provost. Attending those meetings, you start to get an idea of what’s important, from the provost’s perspective. It’s enlightening.”

Thank you, Leslie, for your years of dedication, hard work and service to UC, the Libraries and to the Donald C. Harrison Health Sciences Library. Your work will have a lasting impact on the faculty, staff, researchers and users that rely on the information and services provided by the Libraries. We all wish you the best in your retirement.