Mark Twain and Huck Finn in Cincinnati

By Kevin Grace, University Archivist and Head of the Archives and Rare Books Library

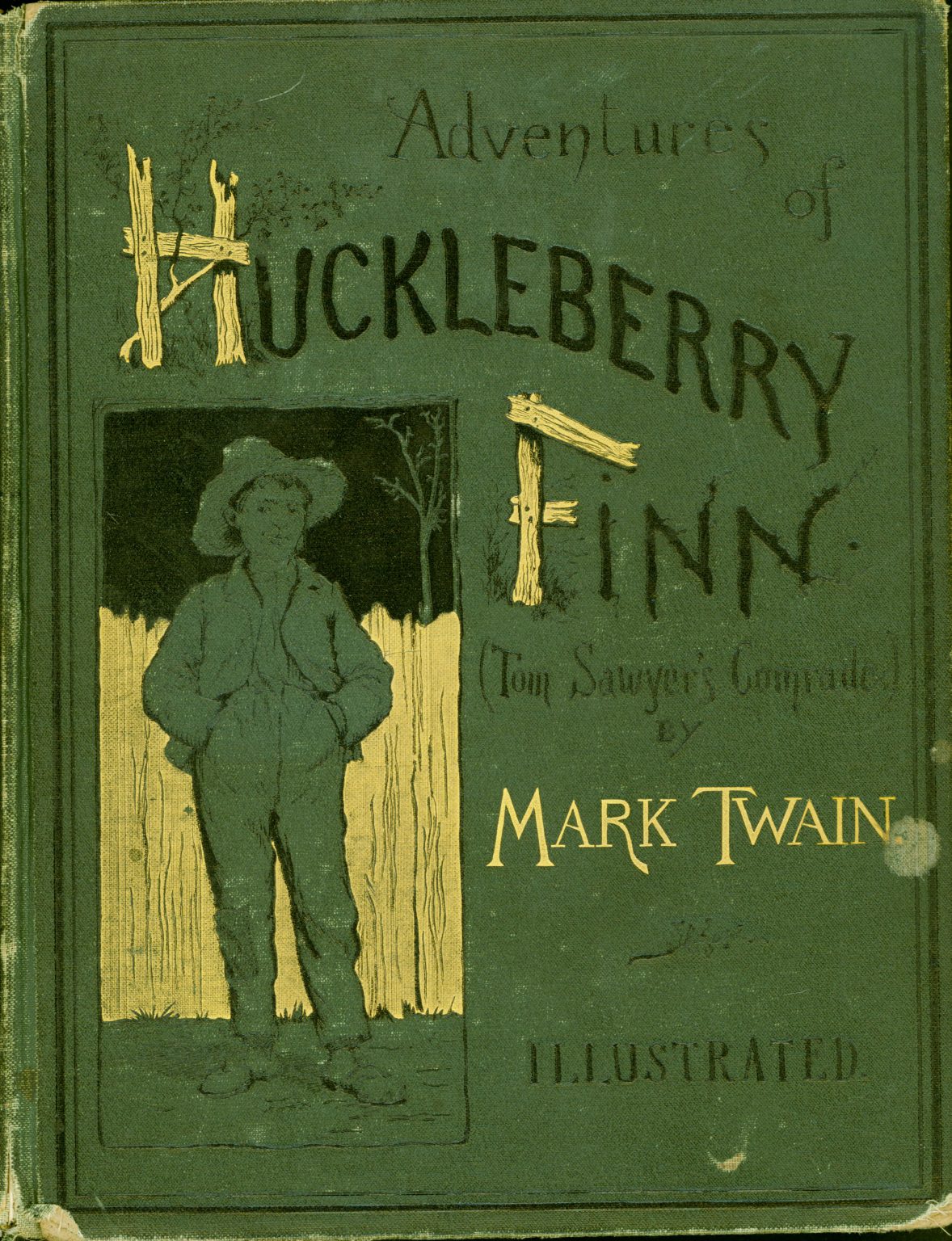

When the University of Cincinnati Libraries held its inaugural Adopt-A-Book Evening, “Hidden Treasures,” a year ago, one of the books exhibited for the event’s attendees was a first edition of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn housed in the Archives & Rare Books Library. Published in America in 1885 (and that date is part of this story), the book was intended to demonstrate “collection building” in UC Libraries fundraising rather than supporting the expenses of physical preservation, which was another designated category used for additional books on exhibit. While the Archives & Rare Books Library (ARB) has a number of Twain first editions in its holdings, Huckleberry Finn stood as an example of further developing of 19th– century American first editions, primary sources that are important for teaching and research in literature courses at UC, as well as classes in publishing, marketing, history, graphic design and political science.

Of course, one thing always leads to another. Exhibiting the volume stimulated some interest in Mark Twain and his relationship with Cincinnati, especially because of that odd quote attributed to him, “When the end of world comes, I want to be in Cincinnati because it’s always 20 years behind the times.” For the record, though, Twain never said it. The spurious statement arose in the 1970s for some reason and there has never been any documentation of him uttering or penning those words. In fact, that sort of sentiment can be traced back to the 18th and 19th centuries: James Boswell said it about Amsterdam, King Ludwig II of Bavaria said it about Dresden, and George Bernard Shaw said it about Ireland. But Twain and the Queen City? It never happened.

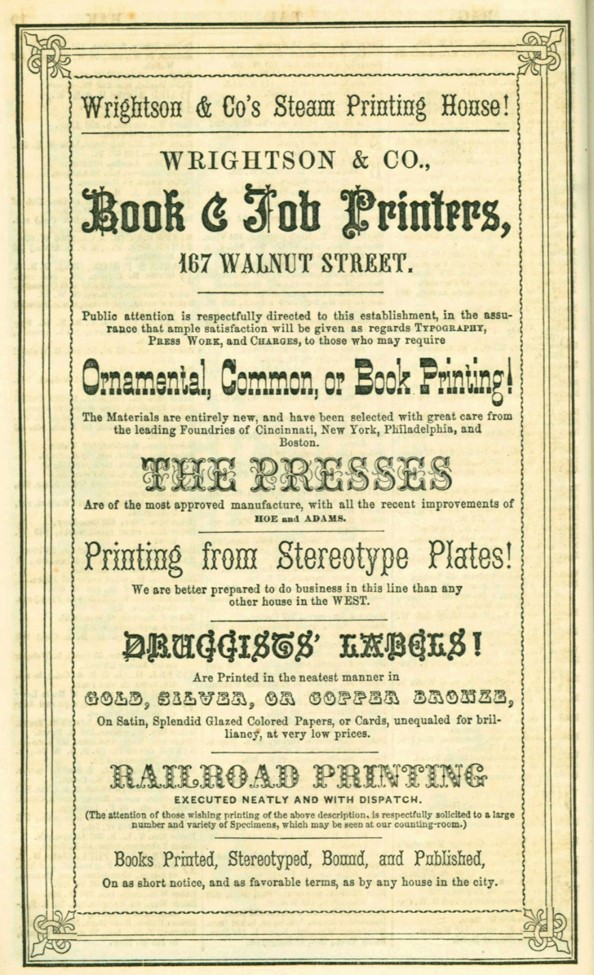

But there are other connections between the author and Cincinnati worth noting. When he was still Samuel Langhorne Clemens and “Mark Twain” was yet to be put to paper, the 20-year old made his way to Cincinnati in the autumn of 1856 to ply his art as a typesetter. Twain first set type in 1853 and before he came to Cincinnati, he worked for his brothers, Orion and Henry, in Keokuk, Iowa. Once he landed in Cincinnati, he was hired by the Wrightson Printing Company at 167 Walnut Street, almost across the street from what is the Mercantile Library today. He didn’t stay long, however. During his printing days, here and there, Twain tried out his writing chops by submitting humorous pieces to newspapers and journals under the pen name “Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass,” which is melodious enough but lacks the snap of “Mark Twain.” By the time spring touched the Ohio River in 1857, Twain was gone to pursue his trade in steam boating. And all he ever said about his first stop in the city is taken from his autobiography: “So I bought a ticket for Cincinnati and went to that city. I worked there several months in the printing office of Wrightson and Company.”

The next connection of Twain and Cincinnati that is known is the result of an unfavorable review of one of his books in 1870. Greg Hand, remembered by the University of Cincinnati community as the longtime spokesman for the university and author of UC books, and who is now the proprietor of the blog Cincinnati Curiosities and a columnist for Cincinnati Magazine wrote about the incident in January of this year. It all had to do with various magazine reviews of Twain’s travelogue, Innocents Abroad. As Hand recounts in his excellent piece, the feud between Twain and the Enquirer, the latter accused the author of lying about his reviews and Twain fought back. Fisticuffs in the form of words were exchanged, with Twain landing the most blows and concluding with “I think the Cincinnati Enquirer must be edited by children.”

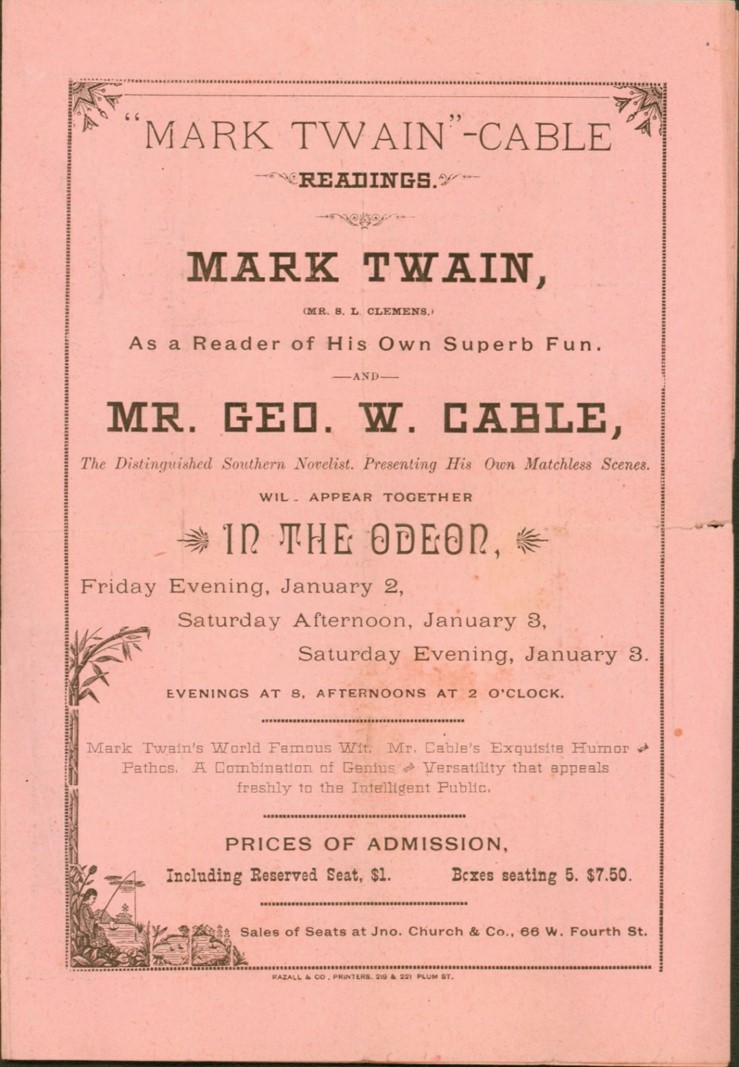

Back to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and forward the Cincinnati connection 15 years. Throughout his career, Twain was the consummate promoter of his books, if not always the best businessman in doing so. He was extremely popular on the lecture circuit throughout the United States and crowds flocked to hear him wherever he toured. It so happened that Cincinnati was on his schedule in January, 1885. Huckleberry Finn was published in England in the fall of 1884, but the novel was a month away from its appearance in America. So Twain hit the road to give selected readings from his work. He was set to speak in the Odeon on Elm Street, the newly-built concert hall for the Cincinnati College of Music (now part of the College-Conservatory of Music at the University of Cincinnati) located next to Music Hall. It stood four stories and seated 1500 people. Appearing with him was the Southern novelist George Washington Cable, who would read from his 1882 book, Dr. Sevier. Twain would read about Huck Finn. According to the flyer printed for the readings on January 2 and 3, the audience would enjoy “Mark Twain’s World Famous Wit. Mr. Cable’s Exquisite Humor and Pathos. A Combination of Genius and Versatility that appeals freshly to the Intelligent Public.” One could have a reserved seat for $1 or a box seat for $7.50. And, according to the advertisements in the flyer, if one was so inclined to enjoy them, the medicated mud baths at 68 W. Seventh Street would effect cures for rheumatism, gout, scrofula, or any sort of blood poison.

The Odeon was packed with appreciative audiences on both days and the authors read as advertised, along with snippets from other of their works – Twain, for example read “The Tragic Tale of the Fishwife,” taken from his 1880 essay, “The Awful German Language.” Interesting, that choice, given the locale.

This time around, the Enquirer editors were more favorable to Twain than was the case several years before. Cable didn’t fare so well: “His colorless face, encircled with abundance of dark hair, did not suggest risible tendencies, and his long pointed beard, suggestive of a cheap stage make-up for the villain’s part, was also against his present calling…When silence obtained he came forward and began the entertainment in a disappointing voice, for it was weak, effeminate, and thin, and had a metallic quality that could scarcely be called agreeable.” But regarding Twain? ”…he enters upon the stage with the self-possessed ease of a man passing into his own drawing-room. The look upon features suggests that he has mislaid his eye-glasses and has returned to look for them…There is not a sentence but what conceals a mirth-provoker of some kind, that jumps out at the most unexpected time and place.” The audiences, the Enquirer noted, roared with laughter at his anecdotes.

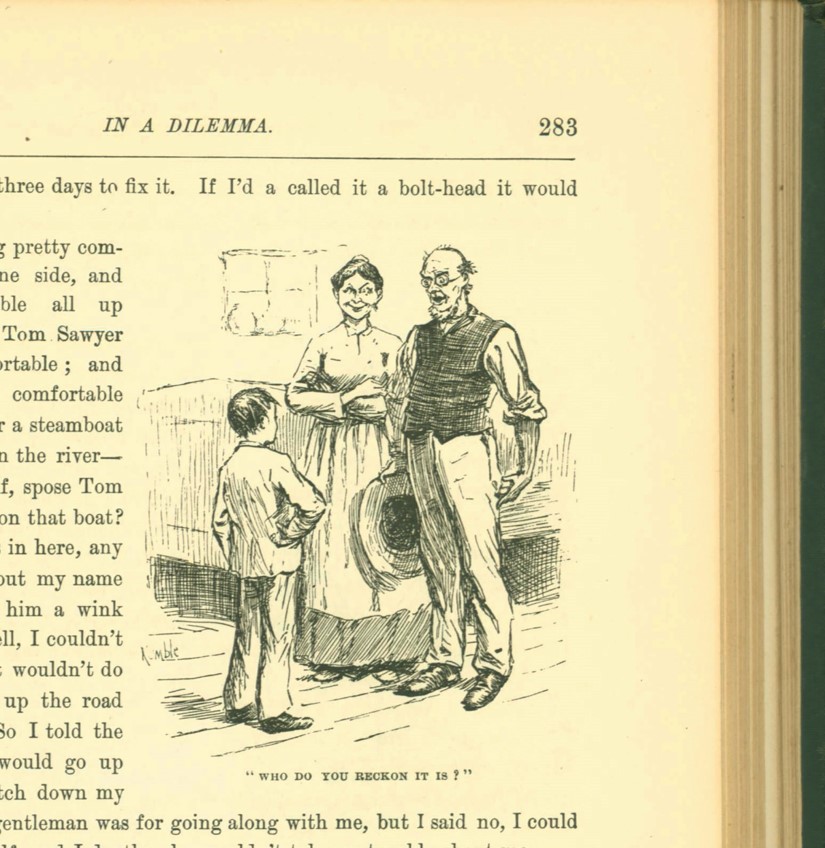

Twain’s Cincinnati readings from the forthcoming Huckleberry Finn, his ninth book, came about in part because of the delay in its American publication. The book was originally set to be issued in mid-December of 1884, along about the same time as the English edition. There was a snag: the book was illustrated by Edward W. Kemble, who himself had a notable career, but one of the many engravers of his work decided to have a bit of fun. On page 283, the illustration of Uncle Silas was altered to show his manhood in an explicit way. Before the ribald re-working was discovered, hundreds of salesman copies and thousands already printed had to be collected so the drawing could be fixed. A $500 reward was offered to find the culprit, but nothing was ever revealed. Except Uncle Silas, of course. It is believed that only one of those bawdy copies has survived. Once the restored Huckleberry Finn was published, Twain could only have been elated because although the New York Times ignored it, complaints poured in from other quarters. In one criticism, the Concord, Massachusetts library condemned it as “veriest trash.” This was great news for the author: Twain believed that it would now “sell 25,000 copies for sure.” Much of the criticism of that era revolved around the use of low class dialect and the characteristics of Huck Finn. In the decades since, the book is regularly excoriated for its language and portrayal of race, and it is steadily featured on lists of banned books.

Over its history of publication, millions of copies of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn have been sold worldwide, but back in 1885 the Cincinnati audiences hearing Twain speak in the Odeon would wait another month until they could buy one.