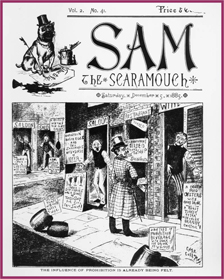

For thirteen months between February 1885 and February 1886, a tabloid publication in Cincinnati published a wide range of articles, cartoons, editorials, and stories that lampooned American life. No topic or person escaped the sharp wit of Sam the Scaramouch, and for the short time this weekly newspaper was in existence, its editors took on national tariffs, elections from Cincinnati to Washington, the temperance issue, urban sophisticates and country bumpkins, race and ethnicity, and, a growing national obsession with sports. Grover Cleveland was president. European colonization of Africa was in full force. The Statue of Liberty arrived in New York, and Ulysses S. Grant died. And, in many ways, Sam was like other newspapers around the country in covering these events, carrying local advertisements and notices, and publishing occasional doggerel and short fiction, and reflecting the “new” journalistic Realism.

For thirteen months between February 1885 and February 1886, a tabloid publication in Cincinnati published a wide range of articles, cartoons, editorials, and stories that lampooned American life. No topic or person escaped the sharp wit of Sam the Scaramouch, and for the short time this weekly newspaper was in existence, its editors took on national tariffs, elections from Cincinnati to Washington, the temperance issue, urban sophisticates and country bumpkins, race and ethnicity, and, a growing national obsession with sports. Grover Cleveland was president. European colonization of Africa was in full force. The Statue of Liberty arrived in New York, and Ulysses S. Grant died. And, in many ways, Sam was like other newspapers around the country in covering these events, carrying local advertisements and notices, and publishing occasional doggerel and short fiction, and reflecting the “new” journalistic Realism.

Sam the Scaramouch was the brainchild of three Cincinnatians: Peter Gibson Thomson, C.V. Van Hamm, and Absalom. H. Mattox. Thomson was a manufacturer of toys, toy books, and games, as well as a printer. Mattox was a commercial clerk, while Van Hamm’s regular occupation is unknown. Altogether, the three of them incorporated their little newspaper, and published it out of a building on Vine Street in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine, a predominantly German neighborhood at the time.

Their pieces in Sam, either written by themselves or solicited from other like-minded gentlemen, were sharply written, disrespectful, irreverent, and funny – everything one could ask of satire. They took their title from a stock character in 19th century Italian theater: “Scaramouch” referred to a boastful, cowardly buffoon, and by the latter part of the century, the term had also come to mean a rascal or scamp. Where the “Sam” part came from, no one knows, Perhaps the editors were just taken with the nice alliteration.

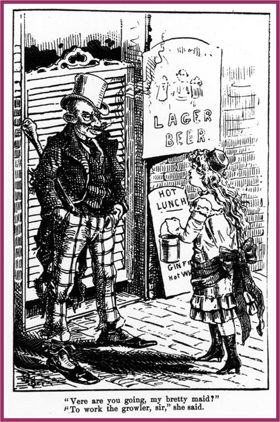

In addition to political issues and international affairs, the editors also directed their barbs at the differences between urban and rural America and at the racial and ethnic groups dwelling in the nation’s cities. As one might expect in a city that was heavily German in 1885, that particular ethnic group came under a great deal of lampooning, with cartoons and dialect stories emphasizing every stereotype from shabby, lecherous Germans accosting young girls outside saloons, to the beginning of various “sausage” seasons. But African Americans, Jews, the Irish, the English, and the Italians were all subject to weekly barbs. The intended readership appears to be those citizens who were educated, politically informed, socially aloof, white, male, and professional.

In addition to political issues and international affairs, the editors also directed their barbs at the differences between urban and rural America and at the racial and ethnic groups dwelling in the nation’s cities. As one might expect in a city that was heavily German in 1885, that particular ethnic group came under a great deal of lampooning, with cartoons and dialect stories emphasizing every stereotype from shabby, lecherous Germans accosting young girls outside saloons, to the beginning of various “sausage” seasons. But African Americans, Jews, the Irish, the English, and the Italians were all subject to weekly barbs. The intended readership appears to be those citizens who were educated, politically informed, socially aloof, white, male, and professional.

There are 432 pages of Sam the Scaramouch, measuring 8 ½” x 10 3/4”, or, 28 cm. It is heavily illustrated with both editorial cartoons and general caricatures. Just twelve libraries, including the University of Cincinnati, report having copies though it is uncertain whether the copies other than UC’s are complete. There is a microfilm of Sam the Scaramouch made in 1983 by the New York Public Library but this microfilm is incomplete and does not include the period from February to June 1885. SpecCol RB F499.C5 S16 1885-1886

– Kevin Grace