By Jameson Tyler, Archives & Rare Books Intern

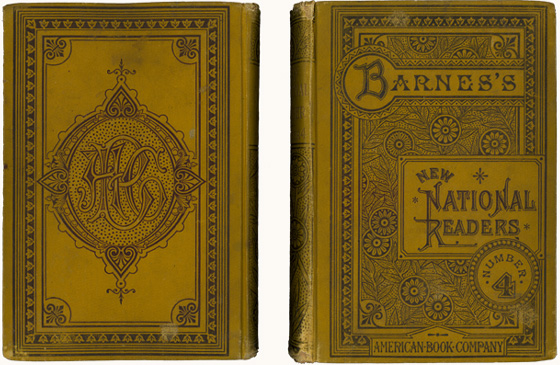

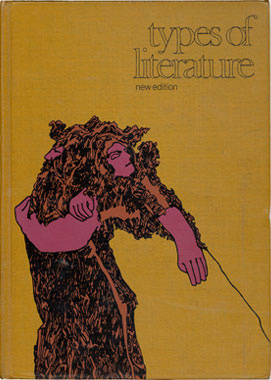

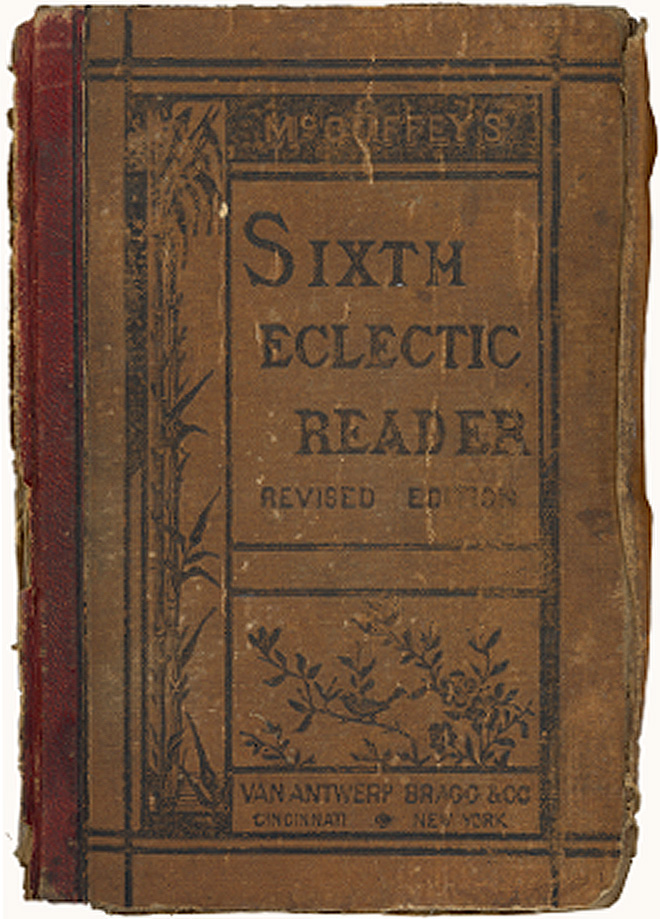

One of the most recent collecting areas in the Archives & Rare Books Library is the Historical Textbook Collection, transferred from the Curriculum Resources Center (now the CECH Library). Created by former CRC librarian Gary Lare, the Historical Textbook Collection is comprised of American textbooks from the 19th century to the end of the 20th. As part of the 2010-2011 ARB intern project, the collection will be organized and fully inventoried, and a collection development policy will be developed. An online exhibit has been initiated (http://www.libraries.uc.edu/libraries/arb/exhibits/historic-textbooks/index.html) to showcase select volumes as well as to provide a “textbook timeline” in the United States and to give a brief history of textbook publishing in Cincinnati. There are, of course, McGuffey readers, along with spellers, science books, history texts, social studies volumes, and the entire range of K-12 education textbooks. It is the aim of this project to position the collection for full cataloging and formal naming.

One of the most recent collecting areas in the Archives & Rare Books Library is the Historical Textbook Collection, transferred from the Curriculum Resources Center (now the CECH Library). Created by former CRC librarian Gary Lare, the Historical Textbook Collection is comprised of American textbooks from the 19th century to the end of the 20th. As part of the 2010-2011 ARB intern project, the collection will be organized and fully inventoried, and a collection development policy will be developed. An online exhibit has been initiated (http://www.libraries.uc.edu/libraries/arb/exhibits/historic-textbooks/index.html) to showcase select volumes as well as to provide a “textbook timeline” in the United States and to give a brief history of textbook publishing in Cincinnati. There are, of course, McGuffey readers, along with spellers, science books, history texts, social studies volumes, and the entire range of K-12 education textbooks. It is the aim of this project to position the collection for full cataloging and formal naming.

After working at Inkling in San Francisco as my last internship, and helping develop enhanced digital textbooks, I had a modest grasp on what it took to bring together all of the resources needed to assemble a textbook, but little knowledge of how the textbook has developed in America. I’ve always been interested in printmaking and publishing, and this seemed like a good opportunity to explore the past of the industry I was trying to move forward with my senior thesis.

After working at Inkling in San Francisco as my last internship, and helping develop enhanced digital textbooks, I had a modest grasp on what it took to bring together all of the resources needed to assemble a textbook, but little knowledge of how the textbook has developed in America. I’ve always been interested in printmaking and publishing, and this seemed like a good opportunity to explore the past of the industry I was trying to move forward with my senior thesis.

While at Inkling, I had the opportunity to work with several major educational textbook publishers, including McGraw-Hill and John Wiley & Sons Inc., with subjects ranging from photography, anatomy/physiology, and public speaking. This gave me a good understanding of the modern structure that most textbooks follow, including chapters containing subchapters, begun by listing concepts and concluded with opportunities to self-test with short-answer questions and glossary terms. Possibly the most surprising differences were the scale of the books and the amount of knowledge in a topic the older textbooks attempted to present in such a noticeably smaller page area. Another interesting aspect to note was the abundance of different typefaces the books are set in, making the 3–5 point size that most modern textbooks are set in look rather sparse, if still very functional and efficient. Something that begs for further research is to find the reasoning behind the smaller size (both in physical  proportions and page count) and whether it was more cost-effective to print this way, or if there was some precedent in other areas of publishing that would cause this practice.

proportions and page count) and whether it was more cost-effective to print this way, or if there was some precedent in other areas of publishing that would cause this practice.

Something I’d never thought about was the westward movement of all the industries that had over a hundred years to develop on the East Coast of the United States, and how much effort it was to start even just a weekly newspaper, a critical medium for spreading information and the only other main source of the time other than word-of-mouth.

After reading The Western Book Trade (1961) by Walter Sutton, I have gained a much better understanding of the publishing legacy of Cincinnati and how modern day exports in that concentration are minuscule compared to what it was in its 19th century prime between the late 1820s and 1910. I look forward to spending more time going through the collection and being able to connect the texts with the history.