When I was reading David M. Oshinsky’s Polio: An American Story awhile back, I noted a book that he briefly mentioned called A History of Poliomyelitis by John R. Paul, MD. I finally got around to looking at this book a little closer, and I thought that I would give you a glimpse into the relationship between Dr. Paul and Dr. Sabin.

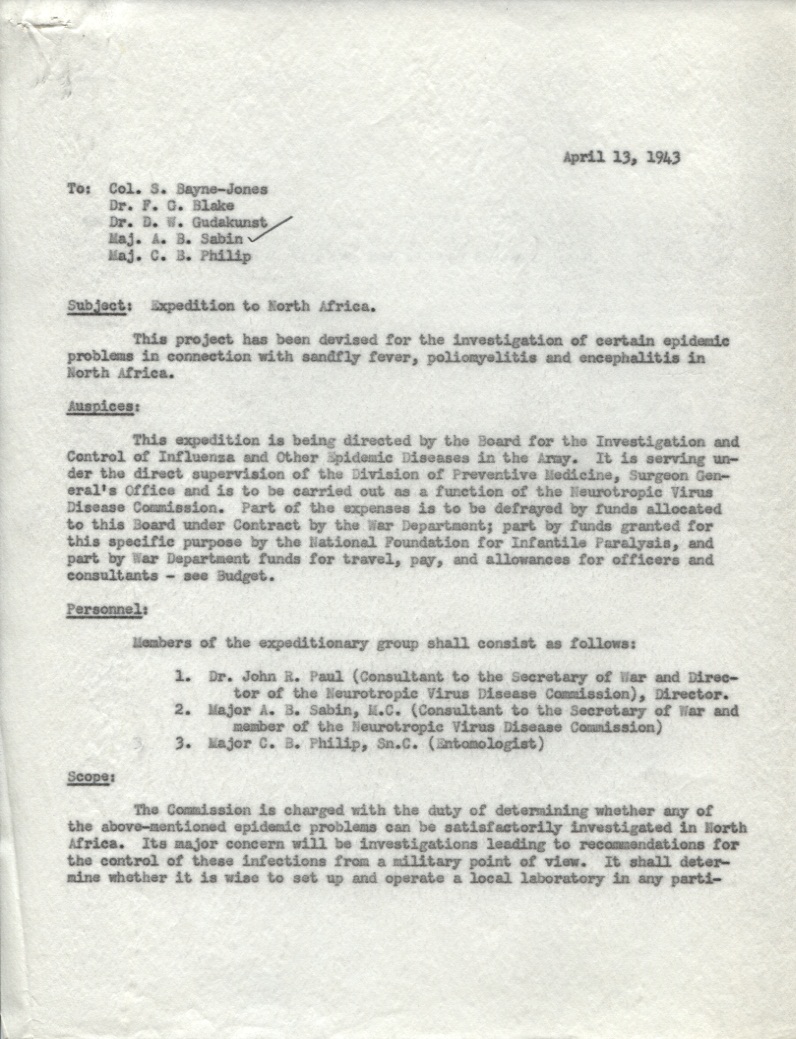

Memorandum from Dr. Francis Blake, President for the Board for the Investigation and Control of Influenza and other Epidemic Diseases in the Army, 1943

According to the Yale University Archives and Manuscripts website, Dr. Paul was at the Yale School of Medicine for over 30 years, where he studied many diseases, including polio. Through his research on this disease, as well as his involvement as director of the Neurotropic Virus Disease Commission of the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board and the Virus Commission during the 1940’s, he and Dr. Sabin corresponded a lot! Our collection has several different folders dedicated to correspondence between Dr. Paul and Dr. Sabin, as well as other letters scattered throughout our Military Service, Oral Poliomyelitis Vaccine, and Poliomyelitis series.

Looking more closely at the Military Service series, one of the folders addresses an expedition to North Africa in 1943. Dr. Paul and Major Sabin (as his letters were signed at that time) went to do research on sandfly fever, poliomyelitis, and encephalitis. According to a memorandum from Dr. Francis Blake, President for the Board for the Investigation and Control of Influenza and other Epidemic Diseases in the Army, Dr. Paul, Major Sabin, and Major C.B. Philips were to conduct investigations “leading to recommendations for the control of these infections from a military point of view.” One thing I found amusing from some of the letters was that they could not figure out how much luggage they were allowed to bring with them on their trip.

A photograph of the Virus Commission in Egypt, 1943. (From Paul's "A History of Poliomyelitis," p. 351, which is in Winkler Center's collection as WC 555 P324h 1971).

Dr. Paul addresses the trip to North Africa in A History of Poliomyelitis (see Chapter 33). The “Virus Commission” a.k.a. Paul, Sabin and Philips, established a base laboratory outside of Cairo and immediately dove into research. The Virus Commission found that there were more cases of poliomyelitis than the Egyptian Ministry of Health was reporting, and foreign troops were acquiring the disease at a higher rate abroad than at home. Paul wrote, “The discovery that poliomyelitis had now attained the status of a military disease was interesting enough and not without practical consequences, but of a far greater importance was the emergence of an understanding of the behavior of the infection in civilian populations in different environments” (p. 356).

Dr. Sabin returned to the United States before Dr. Paul did. Shortly after his arrival, he wrote a letter to Dr. Paul to catch him up on what had happened. Along suggestions for shipping future specimens (“screw cap tops either be selected with great care, or not used at all for this purpose”), Dr. Sabin wrote, “Of incidental interest may be the fact that among my companions on the trip from Algiers to the States were Jack Benny and his troup [sic] […]” From Cincinnati, Dr. Sabin continued research on sandfly fever, while Dr. Paul researched other diseases, including infectious hepatitis. Later letters discuss the progress made on these diseases, as well as a reference to a story about French francs that has me intrigued. Dr. Sabin briefly mentions it as a postscript in a letter from March 1944, saying “I still can not [sic] believe that the story about the French francs is true. Still it is so good that I have had an awful lot of fun telling it.” If I find a letter from Dr. Paul referring to French francs, I’ll be sure to share!

Their paths cross again numerous times over the next couple decades, and their letters were exchanged quite frequently. The next time I discuss their relationship, I want to look at the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, right around the time when Dr. Sabin’s oral poliovirus vaccine was being tested and released. I hope to find more interesting material to share with you!

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $314,258 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to digitize the correspondence and photographs of Dr. Albert B. Sabin. This digitization project has been designated a NEH “We the People” project, an initiative to encourage and strengthen the teaching, study, and understanding of American history and culture through the support of projects that explore significant events and themes in our nation’s history and culture and that advance knowledge of the principles that define America. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.