I finally had a chance to pick up Dr. Saul Benison’s oral history memoir on Dr. Thomas Rivers that I briefly mentioned in a previous blog post, so I thought I would share some information in the book that readers may find interesting. First, I wanted to share a little bit about Thomas Rivers. According to the American Philosophical Society, Dr. Thomas Rivers was an important virologist who was the director of the Rockefeller Institute from 1937-1955, and served as the Medical Director and Vice President for Medical Affairs for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis during his career. Today, Dr. Rivers is considered the father of modern virology.[1]

Dr. Sabin and Dr. Rivers first crossed paths while Sabin was working with Dr. William H. Park at the New York City Health Laboratories, and Rivers was at the Rockefeller. In the memoir, Dr. Rivers describes their first meeting, where Sabin came to tell him about the “B virus,” which he claimed was a new virus. Rivers said, “Well, Sabin was never bashful, and he came to the [Rockefeller] Institute to tell me about his fight with [Dr. Frederick] Gay and to show me his work. I went over his work more than once and finally became convinced that he was right, and so I supported him in his fight with Gay.”[2] A couple years later, Dr. Rivers recommended to Dr. Simon Flexner, director of the Rockefeller Institute, that Sabin be brought on as a researcher. In 1935, Sabin would join the Rockefeller Institute working in Dr. Peter Olitsky’s lab. The memoir discusses Dr. Sabin’s contributions to pathology of polio, where Rivers said, “[…] Sabin did several very nice pieces of work on the pathology of polio, and all of them have one thing in common: they grew out of work that went on in Peter Olitsky’s laboratory at the Rockefeller Institute.”[3]

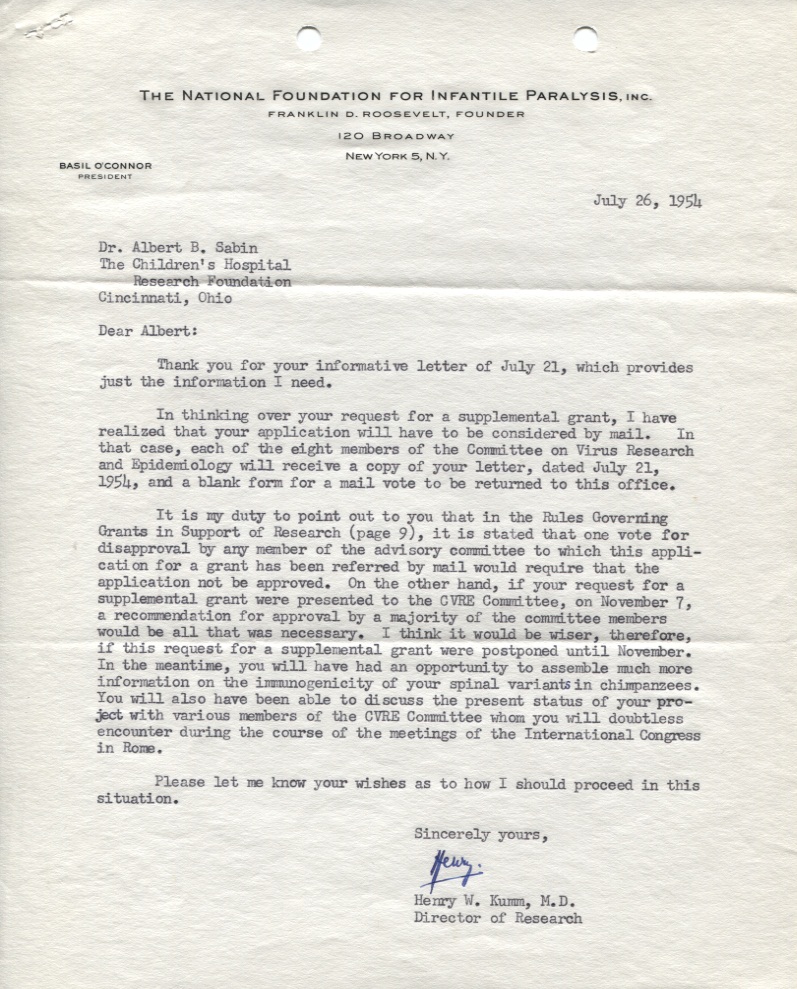

In this July 1954 letter, Dr. Kumm informed Dr. Sabin about the mail vote and the need for unanimous approval.

Later on in the book, Dr. Rivers discusses a couple of things that occurred in 1954, right around the time when Dr. Sabin was applying for more funds from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. He describes Dr. Sabin as an impatient man and relays a story about Sabin requesting a supplementary grant asking for “immediate action.” According to Dr. Rivers, the Virus Research Committee was not to meet for a couple of months, which meant that the application would have to be approved through a mail vote. This type of vote required 100% approval from the Virus Research Committee. As Rivers said, “One vote could have stopped the application, and believe me when I say that there were always one or two guys on the committee who were willing to throw a monkey wrench into the works. Why risk a refusal?” Although things were eventually worked out where Dr. Sabin could receive money through his original grant until the committee could vote on his supplementary grant, “All Sabin could see was that he wasn’t getting what he had asked for,” said Rivers.[4]

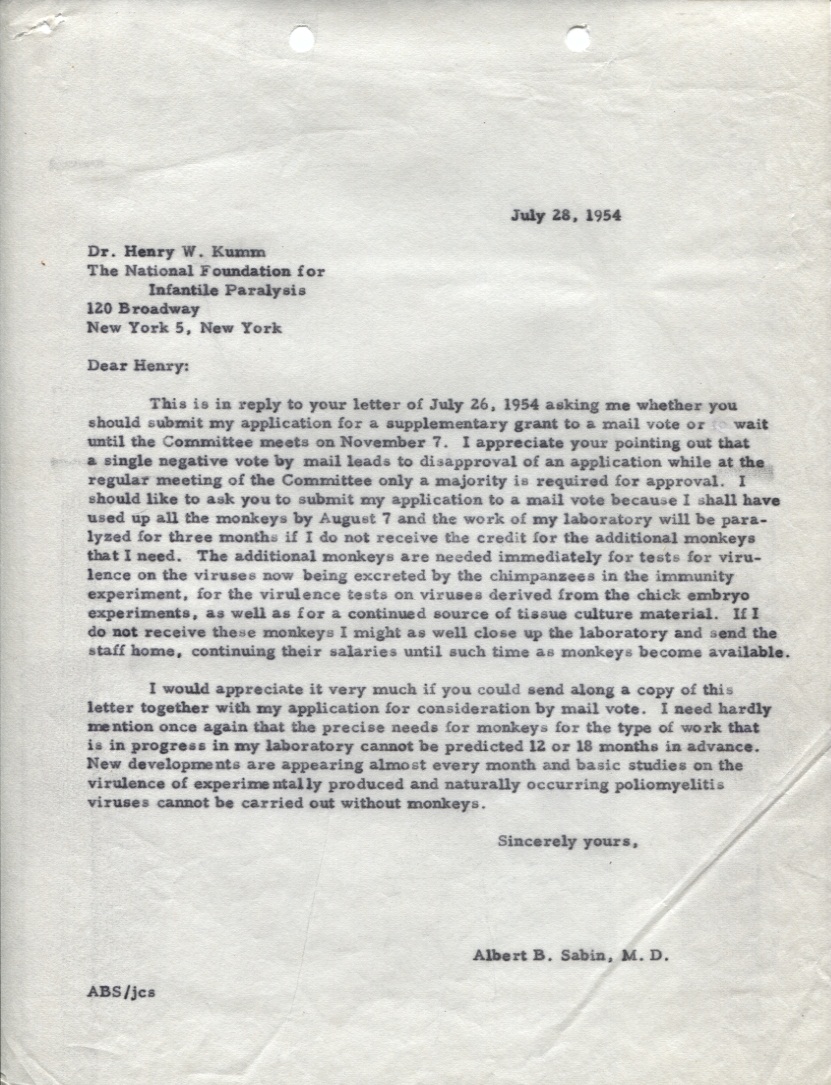

Dr. Sabin's reply to Dr. Kumm expressed his need for more funds to continue his research, which is why he wanted the mail vote.

Looking through some of Dr. Sabin’s letters to and from Dr. Henry Kumm, Director of Research at the NFIP, it looks like Dr. Rivers’ description of Dr. Sabin as “impatient” is true, at least in this case. In the letter seen to the left, dated July 28, 1954, Dr. Sabin wrote to Dr. Kumm, “I appreciate your pointing out that a single negative vote by mail leads to disapproval of an application […] I should like to ask you to submit my application to a mail vote because I shall have used up all the monkeys by August 7 and the work of my laboratory will be paralyzed for three months if I do not receive the credit for the additional monkeys that I need.” Through a telephone conversation the next day, Dr. Kumm and Dr. Sabin agreed that he could use money set aside for chimpanzees so he could purchase monkeys prior to the next Virus Research Committee meeting. [5]

Dr. Rivers also had the opportunity to discuss why Dr. Sabin asked permission from the Virus Research Committee to conduct limited trials with his live viruses in Chillicothe, Ohio. He said, “[…] I think that Dr. Sabin was just acting wisely when he asked the Virus Research Committee for permission to conduct tests with the prisoners at Chillicothe[…] By asking [the committee] first, Sabin was saving time.”[6] In a letter to Basil O’Connor on December 2, 1954, Dr. Sabin wrote, “I should like to take this opportunity also to express my appreciation of the action taken at the recent meeting of the Vaccine Advisory Committee regarding the extension of my studies to human volunteers.” He also noted that he followed the suggestions made by the committee to contact the Director and the Medical Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and they seemed enthusiastic about the proposed studies either in Chillicothe or another suitable facility.[7] According to Rivers, Dr. Sabin’s winter 1954-1955 trial at the Chillicothe prison was a success, and “All the prisoners developed immunizing alimentary tract infections, no viremias were discovered, and no clinical illness resulted.”[8]

In the near future, I’d like to explore more into the relationship between Rivers and Sabin, as well as give a little more detail about Dr. Sabin’s research grants from the NFIP. But in the meantime, check the Sabin blog in the next couple days for our finding aid!

References

[1] David M. Oshinsky, Polio: An American Story, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 18.

[2] Saul Benison, Tom Rivers: Reflections on a Life in Medicine and Science, (Cambridge: The M.I.T. Press, 1967), 234.

[3] Benison, 238.

[4] Benison, 544.

[5] Letter from Dr. Sabin to Dr. Kumm, July 30, 1954. Found in the file located in Series #10- Professional Affiliations and Memberships, Sub-Series Institutions, National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis Box #5, Folder #6 – Grant Applications 1954.

[6] Benison, 544-545.

[7] Letter from Dr. Sabin to Mr. O’Connor, December 2, 1954. Found in the file located in Series #10- Professional Affiliations and Memberships, Sub-Series Institutions, National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis Box #5, Folder #6 – Grant Applications 1954.

[8] Benison, 545.

Note: The Winkler Center owns a copy of Tom Rivers: Reflections on a Life in Medicine and Science in the collection (call number WZ 100 R622a 1967).

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $314,258 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to digitize the correspondence and photographs of Dr. Albert B. Sabin. This digitization project has been designated a NEH “We the People” project, an initiative to encourage and strengthen the teaching, study, and understanding of American history and culture through the support of projects that explore significant events and themes in our nation’s history and culture and that advance knowledge of the principles that define America. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.