I read a recent New York Times obituary of Dr. Renato Dulbecco, a Nobel Prize winning virologist. In 1975, he and his colleagues received the award “for their discoveries concerning the interaction between tumour viruses and the genetic material of the cell.”[1] Although most knew him from his cancer research, Dr. Dulbecco’s earlier research was an important piece of Dr. Sabin’s oral polio vaccine puzzle. The work that they completed together was mentioned in a previous blog post called “A Polio Research Collaboration.”

The obituary called attention to Dr. Dulbecco’s role in oral polio vaccine research by saying, “With Dr. Marguerite Vogt, who became a longtime collaborator, [Dr. Dulbecco] developed a method of determining the amount of polio virus present in cell culture, a step that was essential to the development of the Sabin polio vaccine.”

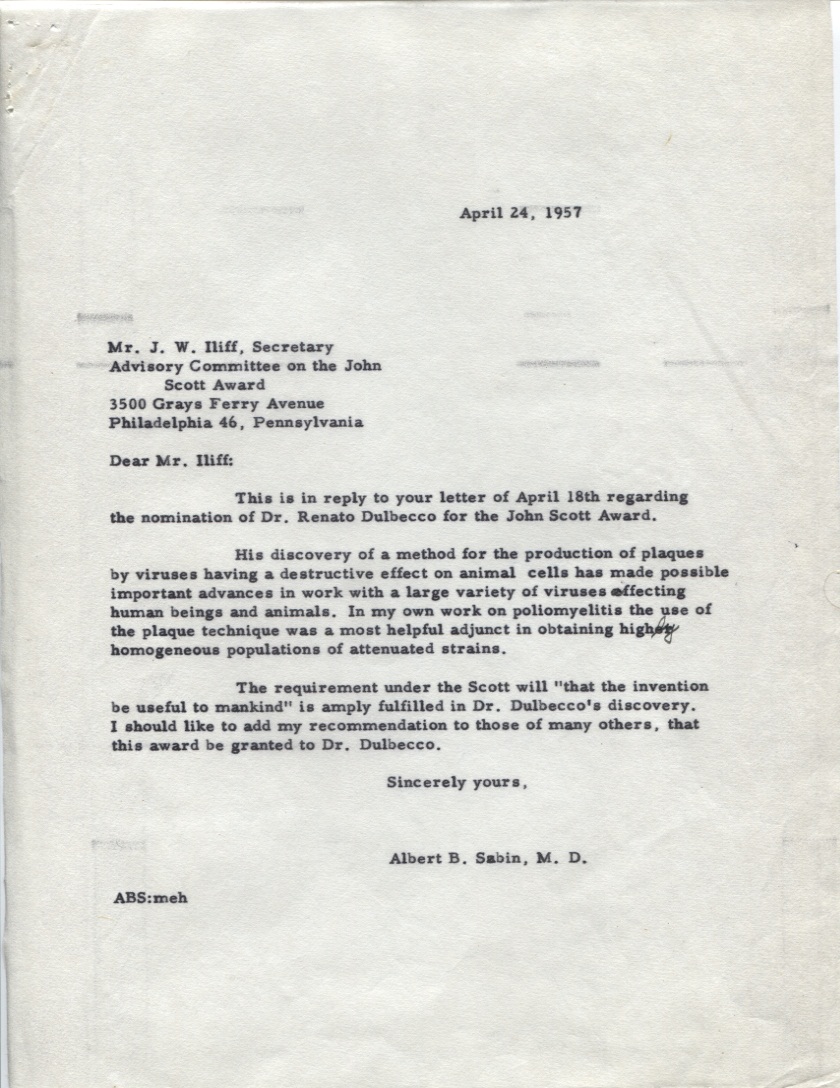

I think Dr. Sabin would have agreed with the statement in the New York Times, especially in light of a 1957 letter found in the archives. Dr. Sabin was asked to write a letter to the John Scott Award Advisory Committee about Dr. Dulbecco and his “method for the production of plaques with animal cells.”[2] Dr. Sabin was approached by the committee on the suggestion of Dr. George W. Beadle, Professor and Chairman of the Biology Division at the California Institute of Technology, where Dr. Dulbecco conducted this research. According to Dr. Beadle, this “monolayer tissue culture method for the quantitative study of such animal viruses as those causing poliomyelitis, Newcastle’s disease, Rous sarcoma, western equine encephalomyelitis, and others” was quite deserving of the John Scott Award.[3]

First awarded in 1834, the John Scott Award was “to be distributed among ingenious men and women who make useful inventions.”[4] Mr. J.W. Iliff of the committee asked Dr. Sabin to speak to how “the invention is useful to mankind.”[5] Dr. Sabin wrote:

His discovery of a method for the production of plaques by viruses having a destructive effect on animal cells has made possible important advances in work with a large variety of viruses affecting human beings and animals. In my own work on poliomyelitis the use of the plaque technique was a most helpful adjunct in obtaining highly homogeneous populations of attenuated strains.

The requirement under the Scott will “that the invention be useful to mankind” is amply fulfilled in Dr. Dulbecco’s discovery. I should like to add my recommendation to those of many others, that this award be granted to Dr. Dulbecco.[6]

With endorsements from Dr. Sabin and others, Dr. Dulbecco was awarded the John Scott Award in 1958.[7] Of course, Dr. Dulbecco didn’t stop there. He continued to contribute scientific discoveries that were “useful to mankind” throughout his long and distinguished career.

References

Note: All of the letters mentioned here can be found in Series #1 – Correspondence, Sub-series – Individual, Box 7, Folder 12 – Dulbecco, Renato – 1954-1963.

[1] “The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1975.”

[2] Letter from Mr. Iliff to Dr. Sabin, 18 April 1957.

[3] Letter from Dr. G.W. Beadle to Mr. Iliff, 3 April 1957.

[4] “Advisory Committee on the John Scott Award. Board of Directors of City Trusts. Philadelphia.” May 1955. (Also found in Dr. Dulbecco’s file in the Sabin collection.) Information can also be found on the John Scott Award website.

[5] Letter from Mr. Iliff to Dr. Sabin, 18 April 1957.

[6] Letter from Dr. Sabin to Mr. Iliff, 24 April 1957.

[7] “The John Scott Award – Award Recipients 1951-1960.”

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $314,258 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to digitize the correspondence and photographs of Dr. Albert B. Sabin. This digitization project has been designated a NEH “We the People” project, an initiative to encourage and strengthen the teaching, study, and understanding of American history and culture through the support of projects that explore significant events and themes in our nation’s history and culture and that advance knowledge of the principles that define America. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.