Throughout the redaction process, I have been asked by many people how we select what should be removed from letters and other documents prior to publication of the materials online. It’s quite a complicated process! A way to approach this question is to discuss things we typically would not remove from letters. One illustration of this concept is through the case of Dr. Sabin’s colleague, Dr. William Brebner.

First, a bit of explanation, just in case you are unfamiliar with the Sabin project. As an archivist, it is part of my “Code of Ethics” to follow principles of “Access and Use” and “Privacy.”[1] Because of the nature of the materials within Sabin project, these principles can come into conflict with each other.

In the Sabin collection there are documents which contain medical research and personal health information. Prior to publishing this material on the web, the Sabin project staff is going through the process of “redaction.” To “redact” a document is to “to select or adapt (as by obscuring or removing sensitive information) for publication or release” or “to obscure or remove (text) from a document prior to publication or release.”[2] By removing information related to medical research or personal health information before publication, the Sabin project staff hopes to balance the issues of privacy and access in a way that will benefit researchers all over the world.

Now back to the case of William Brebner. We have several files in our collection which refer to the “B” virus, which is a virus that was recovered by Dr. Sabin and Dr. Arthur M. Wright in 1932 from a patient who was bitten by a monkey during the course of poliomyelitis research. This man passed away in November 1932 from “respiratory failure secondary to acute ascending myelitis.”[3] A New York Times obituary appeared on November 10, 1932, with the headline “Bite by a Monkey Fatal to Physician” and identifies the physician as Dr. W. B. Brebner.[4] Other obituaries, which appeared in journals such as Archives of Pathology[5] and The Canadian Medical Association Journal[6] also described Dr. Brebner’s fate.

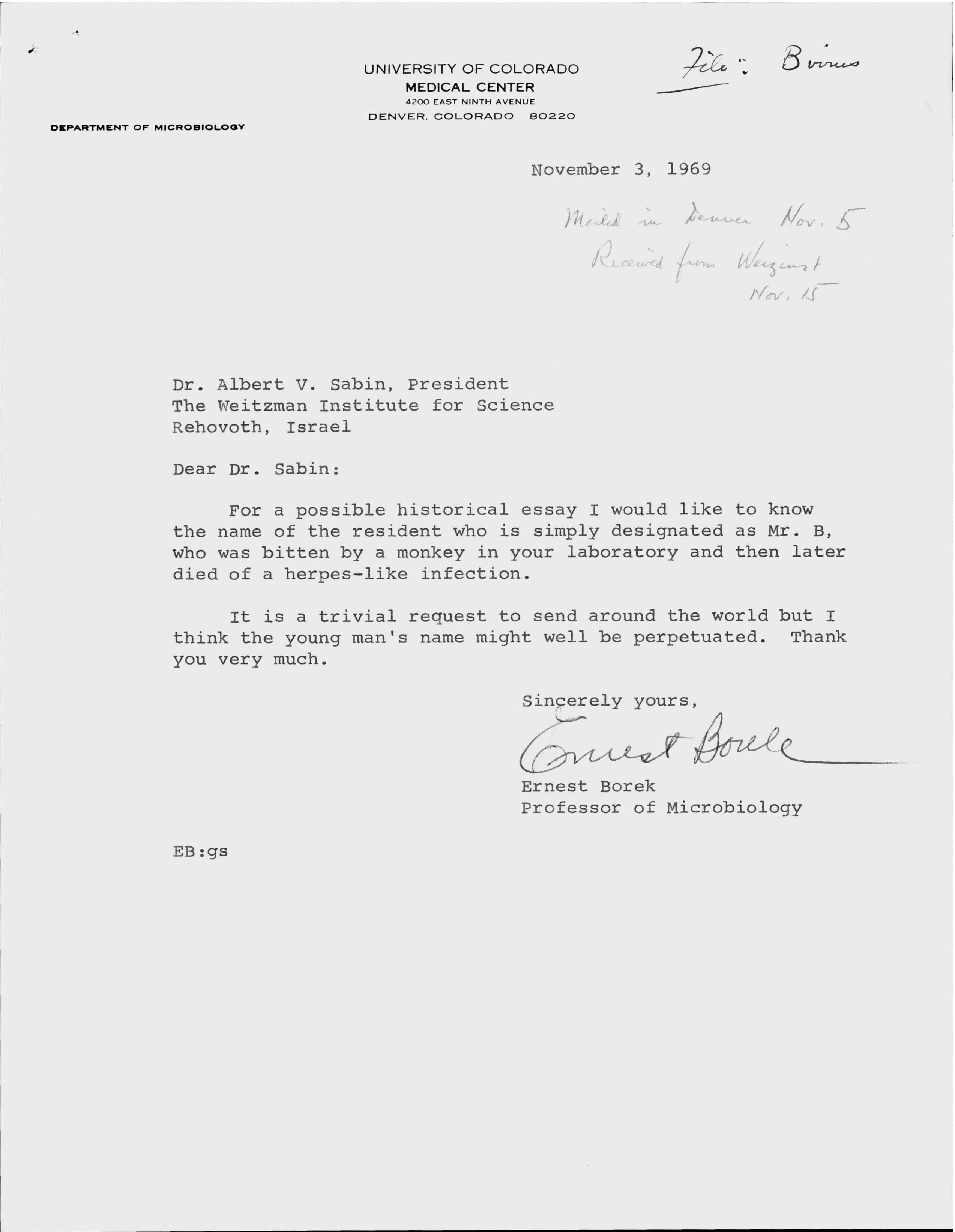

Years later, Dr. Sabin received letters asking about the origin of the “B” virus, such as the one seen above from Professor Ernest Borek. He wrote, “For a possible historical essay, I would like to know the name of the resident who is simply designated as Mr. B, who was bitten by a monkey in your laboratory […] I think the young man’s name might well be perpetuated.”[7] Dr. Sabin explained to Professor Borek and other researchers that he had wished to call it the Brebner virus, but the editor of the Journal of Experimental Medicine, where his research was originally published, “insisted that only the ‘B’ be used.”[8]

The association with Brebner and the “B” virus appears in later journals, such as a 1985 article on Dr. William H. Park, who ran the laboratory where both Brebner and Sabin worked in the early 1930’s. There it describes how “intern Sabin obtained tissue specimens from which he isolated a hitherto unknown virus which he named B virus, after Brebner. It was later shown that this member of the herpesvirus group was carried by otherwise healthy macaque monkeys.”[9] The author concluded that Dr. Sabin’s experience with the “B” virus and Dr. Brebner may have influenced his career in fighting poliomyelitis and other viruses.[10]

In order to maintain links and connections between the Sabin collection and previously published research, we have chosen not to redact Dr. Brebner’s name in any correspondence. We hope that preserving names in cases such as this will assist future researchers who use the collection.

Over the last year of this project, Winkler Center staff have put forth much effort to protect the privacy of those mentioned in the documents, including the creation and implementation of our redaction policy. Through this redaction process, we are attempting to redact documents in an appropriate manner and provide access to an important medical collection. As one of the largest digitization projects of a medically related materials (that we know of), in many ways, we are breaking new ground. Once our material is up and running online, we will welcome users’ feedback with regard to these issues and other topics.

References

[1] See the SAA Code of Ethics for Archivists.

[2] See the definition of redact.

[3] Jason D. Pimentel. “Herpes B Virus – “B” is for Brebner: Dr. William Bartlet Brebner (1903-1932).” CMAJ 178 (2008): 734. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2263097/

[4] “Bite by a Monkey Fatal to Physician.” New York Times. Nov. 10 (1932): 24.

[5] E.V. Cowdry. “Obituary: William B. Brebner, 1903-1932.” Archives of Pathology 15 (1933): 133.

[6] “Obituaries.” CMAJ 27 (1932): 683.

[7] Letter from Ernest Borek to Albert B. Sabin, dated November 3, 1969. Found in Series 1 – Correspondence, Subseries General, Box 1, Folder 3 – B Virus, 1958-69.

[8] Letter from Albert B. Sabin to George Dick, dated November 8, 1969. Found in Series 1 – Correspondence, Subseries General, Box 1, Folder 3 – B Virus, 1958-69.

[9] M. Schaeffer. “William H. Park (1863-1939): His Laboratory and His Legacy.” American Journal of Public Health 75 (1985): 1300. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1646692/

[10] Ibid., 1301.

In 2010, the University of Cincinnati Libraries received a $314,258 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to digitize the correspondence and photographs of Dr. Albert B. Sabin. This digitization project has been designated a NEH “We the People” project, an initiative to encourage and strengthen the teaching, study, and understanding of American history and culture through the support of projects that explore significant events and themes in our nation’s history and culture and that advance knowledge of the principles that define America. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.